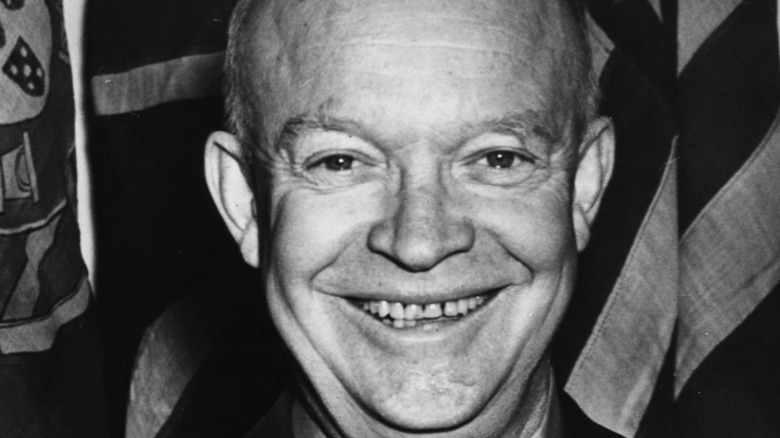

Questionable Things About Dwight D. Eisenhower's Presidency

When Dwight. D. Eisenhower, affectionately known as Ike, took over the United States' presidency in 1953 the country was at a crossroads. The Korean War was raging in Asia, the Cold War with Russia was quickly gaining steam, and internal racial strife was threatening to tear the country apart from within. Eisenhower had previously led huge armies into battle in Northern Africa and France during World War II, but governing a country as a politician and statesman was a very different task. He had no congressional or political experience before being elected president and had most recently served as the president of Columbia University in New York prior to taking office (via the White House).

Yet, during his two-term presidency Eisenhower presided over one of the most prosperous times in American history. There was strong economic growth, he created the Interstate Highway System, and he managed to avoid war with the Soviet Union at a time when tensions were incredibly high (via the Miller Center). Eisenhower managed to effectively control and address issues while working out of the spotlight and often behind the scenes.

However, for as impactful a leader as Eisenhower was, there were certainly controversial aspects to his presidency.

His administration planned the Bay of Pigs invasion

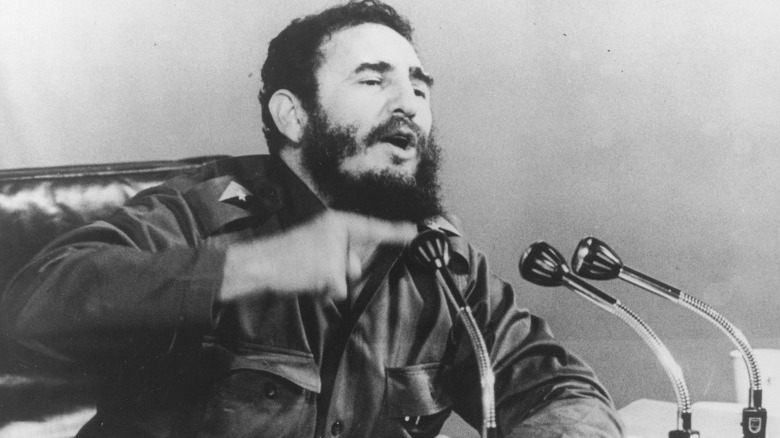

The Bay of Pigs invasion was one of the biggest disasters in U.S. covert history. The CIA trained and armed over 1,400 exiled Cubans to land back in Cuba to overthrow Fidel Castro's new government (via the JFK Library). But the invasion was a complete failure; more than 100 of the CIA trained paramilitaries were killed by the Cuban army and another 1,200 surrendered within a few days. The president at the time, John Kennedy, is widely blamed for the fiasco, but it was not entirely his plan.

The conception, planning, and training actually all occurred during the Eisenhower Administration. After Castro initially came to power in early 1959 there were hopes within the administration that he would not be a communist and that he would work with the CIA, according to Tim Weiner in "Legacy of Ashes: The History of the CIA." However, that quickly soured, and by the spring of 1960 Dwight D. Eisenhower had assented to covert action to remove Castro from power.

That August, during a meeting with the Director of the CIA Allen Dulles, Eisenhower agreed to start a nearly $11 million program that would become the Bay of Pigs invasion. The CIA quickly set up training camps in Guatemala to train the Cubans, and by November 1960 they were ready to invade (via the JFK Library). The invasion did not take place until JFK's presidency in early 1961, at which point it dramatically failed.

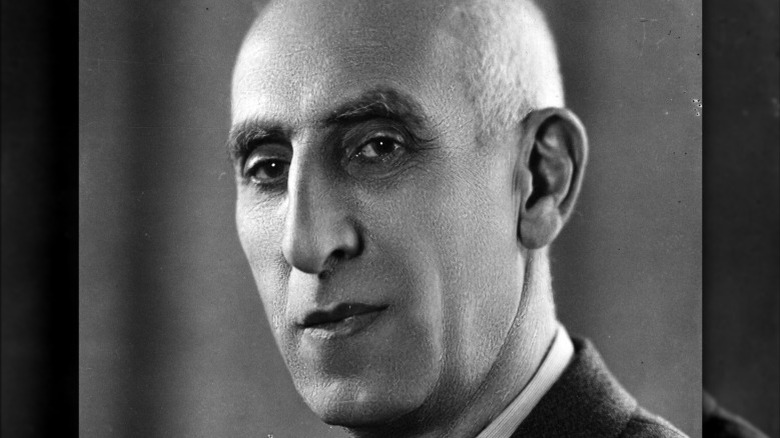

His administration helped overthrow the Iranian government

One of the most controversial decisions of the Eisenhower Administration was the CIA's involvement in the 1953 Iranian coup d'état. Prior to 1951, the British had controlled the Iranian oil industry through the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company (AIOC), writes John Prados in "Safe for Democracy." However, the AIOC mainly served to enrich the interests of British shareholders instead of the Iranian government and citizens. Eventually, the Iranians started to grumble about nationalizing the industry to preserve the oil profits for Iran instead of Britain.

In spring 1951, a new Iranian Prime Minister, Muhammad Mossadegh, led the Majlis (Iranian parliament) into absorbing the AIOC and the oil industry. An outraged British government tried to enlist the help of the U.S., but the Truman Administration refused to acquiesce in any plans to overthrow Mossadegh through a coup d'état.

However, when Dwight D. Eisenhower took office in early 1953, the British once again tried to get the U.S. to agree to participate in planning a coup (via Stephen Kinzer in "Overthrow"). Within two months, Eisenhower had agreed, and the CIA director immediately started working with the British and Iranians on the plot. The plan was to bribe political, religious, and popular leaders to create opposition to Mossadegh within Iran. CIA agent Kermit Roosevelt (Theodore Roosevelt's grandson) led the operation and got the Iranian Shah to agree. That August, Mossadegh was ousted, and the trajectory of Iranian history was forever altered.

The CIA under his administration organized the 1954 Guatemalan coup d'état

Fresh off the Iranian coup from 1953, the Eisenhower Administration decided initiating coups was a viable tactic that could be repeated in Guatemala the following year. There, a young leader named Jacobo Árbenz had come to power in 1951 in the midst of Guatemalan Revolution (via Stephen Kinzer in "Overthrow"). One of his first tasks was to break the hold of the United Fruit Company (UFCO) on the Guatemalan economy. UFCO controlled the economy through becoming Guatemala's largest employer and private landowner, utilizing a tax-free lease on massive amounts of land.

In 1953, the Árbenz government seized 234,000 acres of land from UFCO under a newly passed Agrarian Reform Law. They offered them $1.1 million in compensation, the land's declared taxable value, but UFCO balked and demanded $18 million more — the land's real taxable value that they had been deliberately undervaluing for years. Several former UFCO executives had made their way into the Eisenhower Administration, and when the Árbenz government seized the land the former executives immediately decried the move as illegal and communist.

Soon, the CIA was working on a covert plan to overthrow the Guatemalan government due to the land seizure, which they codenamed "Operation Success," and Dwight D. Eisenhower approved the plan in late 1953. The operation kicked off the following June 18, and by the 27th Árbenz had been deposed as president, Kinzer writes.

The various CIA assassination attempts against Fidel Castro

One of the least savory aspects of the Eisenhower Administration was the myriad of CIA plots to assassinate the prime minister of Cuba, Fidel Castro. After Castro had come to power in Cuba in late 1959, he had quickly drawn the ire of Washington with his overtures and public messaging towards the Soviet Union, as per the CIA. In response, Dwight D. Eisenhower authorized the CIA to take out Castro and save Cuba from the throws of communism.

According to John Prados in "Safe for Democracy," on one track, the CIA was planning for the Bay of Pigs invasion by training Cuban paramilitaries, but on the other track they were planning to eliminate Castro. One of the earliest plots was to sprinkle radioactive chemicals onto Castro's shoes, with the idea that they would cause his hair to fall out and make him look weak and vulnerable. Other plans involved the CIA recruiting members from the Italian Mafia to carry out a hit on Castro. The Mafia was inclined to work with the CIA because Castro had destroyed their hold on the Cuban gambling industry by making gambling illegal.

Some of the other fantastical plot ideas that Prados details included infecting a box of Cuban cigars with lethal chemicals that would kill Castro after he smoked them and getting him to unknowingly eat capsules filled with poison bacteria. These were to be carried out by the CIA's Mafia contacts, but they all fell through.

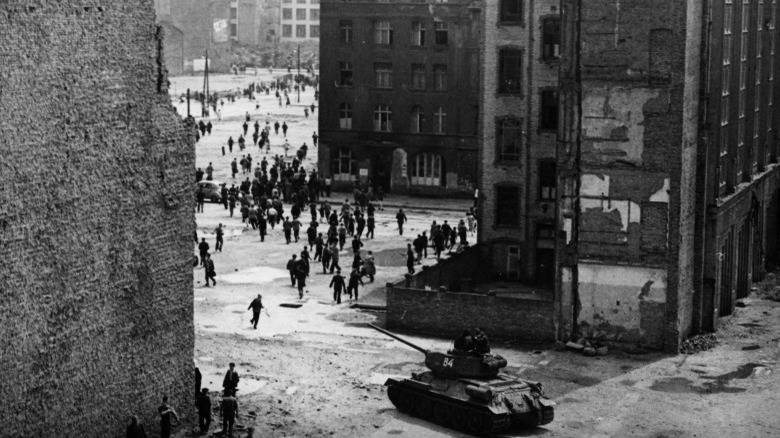

His failed response to the 1953 Berlin Riots

When the Eisenhower Administration took office in early 1953, some people saw it as a potential opportunity for the U.S. and the Soviet Union to reduce their tensions with each other. Joseph Stalin had died that March, so both countries had new leaders for the first time since the end of WWII. However, the Eisenhower Administration wanted nothing to do with that, according to Ronald Powaski in "The Cold War: The United States and the Soviet Union, 1917-1991."

The administration frequently used rhetoric and talked about liberating the "captive peoples" under the yoke of communism, leading many to believe the president would start a fight against communism in central and eastern Europe. However, when confronted with an opportunity to support the East German citizens rebelling against their Soviet rulers, Dwight D. Eisenhower completely whiffed. In mid-June 1953, just shy of 400,000 Eastern German citizens started to revolt and rebel against the Soviet government, marching through the streets and burning communist party regalia, writes Tim Weiner in "Legacy of Ashes." The Soviet government immediately sent a contingent of tanks to quell the rebellion, which they put down quickly.

Yet, instead of supporting the rioting East Germans in their struggle against the Soviets, Eisenhower barely uttered a word of protest. The CIA refused to help any of the rebels, realizing their tactics and planning was wholly inadequate to covertly take on the Soviet menace.

Ignoring the Geneva Conference on Vietnam

In early 1954, the U.S. and other major world powers held a peace conference in Geneva. The conference was partly created to solve the ongoing war between France and the Viet Minh nationalist army in Vietnam (via History). After years of war, the Viet Minh had taken over the French base at Dien Bien Phu, and the French decided to sue for peace at Geneva.

From the beginning, the EIsenhower Administration did not like the inclusion of Vietnam at Geneva, notes David Anderson in "Trapped by Success: The Eisenhower Administration and Vietnam, 1953-1961." The U.S. delegation to Geneva was determined to stay out of the spotlight, with the sole intent of trying to prevent the communist takeover of Southern Vietnam. The final agreement stated there would be two different Vietnams, and that refugees were free to cross the border to choose which Vietnam they wanted to live in. The Eisenhower Administration specifically pledged to not use force to interfere or disturb the agreement.

However, it was a bold faced lie. That June, the CIA had already sent in the Saigon Military Mission (SMM) to disrupt affairs in the north and convince refugees to come south, by planting stories about communist massacres and a brutal Chinese occupation, reports The New York Times. They also blew up vehicles, destroyed fuel and oil supplies, organized a group of commandos, and buried weapons in cemeteries in preparation for an uprising (via Tim Weiner in "Legacy of Ashes").

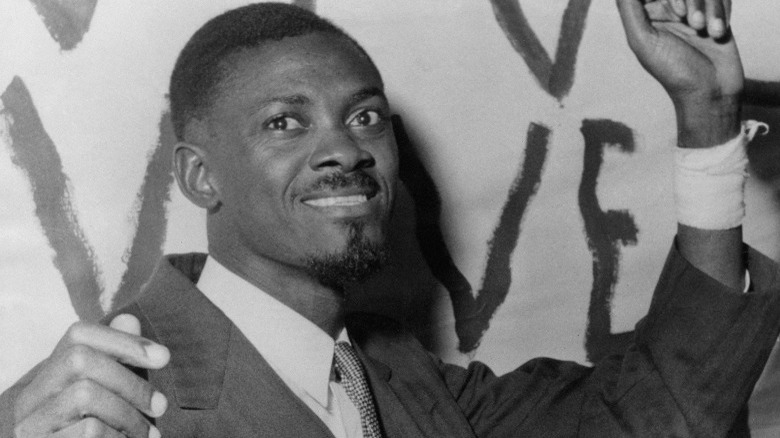

The death of Patrice Lumumba

In 1960-1961, the policies of the Eisenhower Administration would lead to the unfortunate death of Congolese Prime Minister Patrice Lumumba. In 1960, Belgium was on the verge of granting the Congo their independence, when infighting broke out in the army between the Congolese soldiers and Belgian officers (via Ronald Powaski in "The Cold War"). Lumumba was unable to quell the rebellion and asked for Dwight D. Eisenhower's assistance, but after Eisenhower rejected his request Lumumba instead appealed to the Soviet Union — and they immediately supplied him with trucks, air transports, and manpower.

Eisenhower's Administration rejected Lumumba's request because they had already pegged him as a communist, writes Tim Weiner in "Legacy of Ashes." Instead, they threw their support to a colonel in the army, Joseph Mobutu, who quickly seized power with $250,000 of CIA help.

Reportedly, Eisenhower instructed CIA station chief Larry Devlin to kill Lumumba by injecting lethal chemicals into his food or drink, which he refused to carry out — but in the end it didn't matter. The CIA had already recruited Mobutu to work with them, and he arranged for Lumumba to be captured and delivered to the Belgians. The Belgians murdered Lumumba just two days before Eisenhower's term officially ended, and the U.S. went on to support Mobutu's vicious rise to power in the Congo.

Almost going nuclear over Taiwan in the 1950s

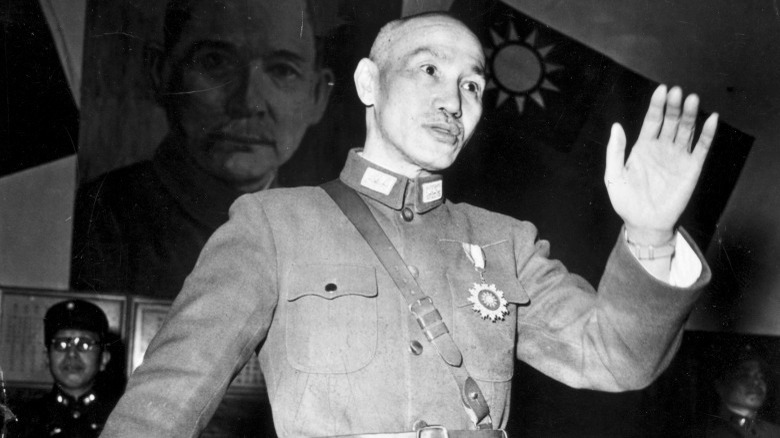

The split between the People's Republic of China and the Republic of Taiwan in 1949 had momentous ramifications for U.S. foreign policy. That year, the Mao Zedong-led communists defeated Chiang Kai-shek and the Chinese nationalists in a ferocious civil war. Mao forced Chiang and his followers, known as the Kuomintang, to flee the mainland and take refuge on the islands of Taiwan (via the State Department's Office of the Historian).

Chiang was eager to get back to China and take back power from the communist government, but the Truman Administration was lackluster in their commitment to the Kuomintang, as per John Lewis Gaddis in "The Cold War: A New History." Following the 1954 Geneva Conference, the Chinese communists decided to take a shot at the Kuomintang and began shelling their islands as a show of force. The Eisenhower Administration immediately responded with a treaty to aid in the defense of Taiwan, but that only settled matters for a short time. In 1958, Mao again decided to start shelling the Taiwanese islands of Quemoy and Matsu to antagonize Dwight D. Eisenhower and Chiang.

However, this time Eisenhower responded with more than just treaties, he threatened to use nuclear weapons if Mao did not relent. Eventually, the crisis was settled without any nuclear explosions, but it was certainly a tense time in American history.

Failing to support the Hungarian people during the 1956 Revolution

In February 1956, Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev made one of the most shocking speeches in Russian history when he denounced the rule of former Soviet leader Joseph Stalin, as per Tim Weiner in "Legacy of Ashes." The next month, the CIA and Eisenhower Administration had a copy of the speech, and they immediately saw its utility as a propaganda tool. By June they were streaming recorded versions of the speech to millions of Eastern Europeans through Radio Free Europe, hoping to sow discord and uncertainty about the communist party's leadership.

Though CIA analysts had assumed the broadcasts were likely to be ineffective, they actually made a huge impression on its Eastern European audience. In June, Polish workers started to rebel against their communist government, and Dwight D. Eisenhower's CIA ramped up their efforts to create "spontaneous manifestations of descent" and more chaos. A new government came to power in Poland with Khrushchev's blessing, but when a similar uprising occurred in Hungary that October, he moved to crush it immediately (via Ronald Powaski in "The Cold War").

Eisenhower had encouraged these types of rebellions, repeatedly urging the Europeans to rise up against their commmunist rulers and become free. However, when Soviet tanks rolled into Hungary, Eisenhower did nothing. The Soviets killed 25,000 Hungarians and forced another 200,000 to flee the country. The Eisenhower Administration was never prepared to actually confront the Soviets, and their encouragement of rebellion partly led to the deadly uprising.

The Berlin Crisis

Following the end of World War II, the Allied occupation of Germany and Berlin became a flashpoint for tension several times. In 1948, the Soviet Union had blocked Western access to West Berlin, which was located in East Germany. The U.S. had to resort to air drops to supply the helpless Berliners until the border was reopened, according to the State Department's Office of the Historian. Ten years later, in 1958, both the Soviet Union and U.S. were under new leadership, but the problem of Berlin remained.

In November that year, Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev gave President Dwight Eisenhower an ultimatum on West Berlin: either withdraw all of the Western troops or the Soviets would hand over control of access rights to the East Germans, as per John Lewis Gaddis in "The Cold War: A New History." This was bound to create issues

Eisenhower invited Khrushchev to a conference in Geneva, and though that failed to bring a solution the deadline passed without any change to the status of access rights, notes Ronald Powaski in "The Cold War: The United States and the Soviet Union, 1917-1991." Khrushchev ended up traveling to America, where he was received by the Eisenhower Administration for a trip to various landmarks in the country. However, this far from ended disputes over Berlin. Eisenhower merely kicked the can down the road to his successor John Kennedy, and the Berlin Wall went up in mid-1961.

The Gary Powers U-2 Spy Plane incident

During the Cold War, the U.S. and the Soviet Union were intensely worried about the other having more nukes and missiles to shoot them with. Keeping track of the other side's arsenal build up was crucial, and in the 1950s, the CIA under the Eisenhower Administration came up with a new tool to secretly spy on the Soviets: the U-2 spy plane, thought to be undetectable (via the State Department's Office of the Historian).

On May 1, 1960, a U-2 plane piloted by Gary Powers was shot down over the Soviet Union while making a flight, writes Tim Weiner in "Legacy of Ashes." Dwight D. Eisenhower, trying to save face, initially lied about what happened and told the American public that they had lost track of a weather plane in Turkey and mentioned nothing about Powers or the U-2. However, seven days later the Soviets blew the lid off the affair when they announced the capture of Powers and the plane, as per Ronald Powaski in "The Cold War." Eisenhower refused to apologize, and the upcoming summit between him and Nikita Khrushchev was canceled. Diplomatic relations between Eisenhower and Khrushchev never recovered, and all future plans for talks were shelved for the remainder of his presidency.

He contributed to the Lavender Scare

One of the most shameful moral failings of the U.S. government was the Lavender Scare from the late-1940s to the early-1960s. And unfortunately, Dwight Eisenhower was directly involved in it. The Lavender Scare was a period where thousands of federal employees were forced to resign or faced termination just for being homosexual (via Prologue Magazine). It was intimately wrapped up with the Red Scare, which was a similar ill-conceived witch hunt to root out communist subversives within the government.

Eisenhower's responsibility for inflaming the Lavender Scare lies with Executive Order 10450. Eisenhower issued the order in 1953, which began the operation to investigate homosexual federal employees, including questioning them about their private lives, and subsequently removing them from their jobs (via Time). The order explicitly stated that an individual's sexuality was now going to be under scrutiny, which essentially meant the banning of all gay and lesbian employees from the federal government, as per Prologue Magazine.

Though there are no official statistics, estimates put the range as low as 5,000 and suggest that tens of thousands of individuals may have lost their jobs from the Lavender Scare. In addition, scores of homosexual employees did not apply for government service for fear of being outed and fired during their employment.