Questionable Things About JFK's Presidency

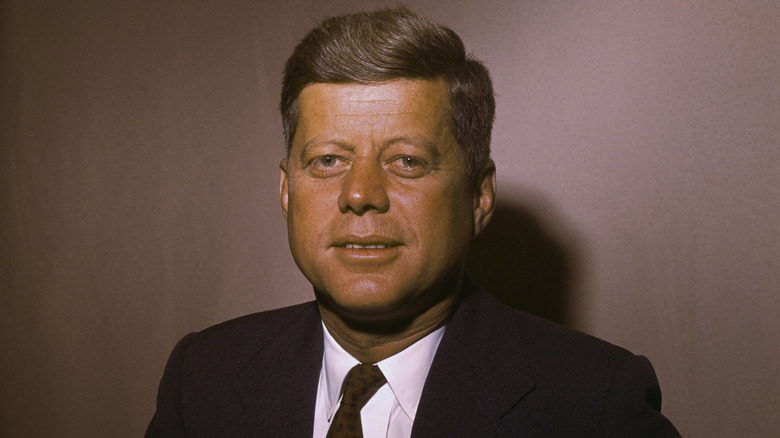

Historians have typically considered the administration of President John F. Kennedy one of the better ones. According to a 2021 poll from C-SPAN, historians ranked JFK the eighth-best president in history, slightly down from sixth in 2009.

It's not hard to see why. Kennedy has always been revered for his charisma, style, and strong leadership in times of crisis. His ability to get the Limited Test Ban Treaty done in the midst of a nuclear arms race with the Soviet Union was impressive, to say the least. Tragically, Kennedy's assassination by Lee Harvey Oswald cemented his legacy as one of the most beloved presidents of the 20th century.

However, not everything about the Kennedy administration was positive. His memory has been dogged by rumors about his private life, JFK's assassination has been the subject of bizarre conspiracies, and that's just the tip of the iceberg. These are the most questionable things about JFK's presidency.

JFK's flap with Nixon on the campaign trail

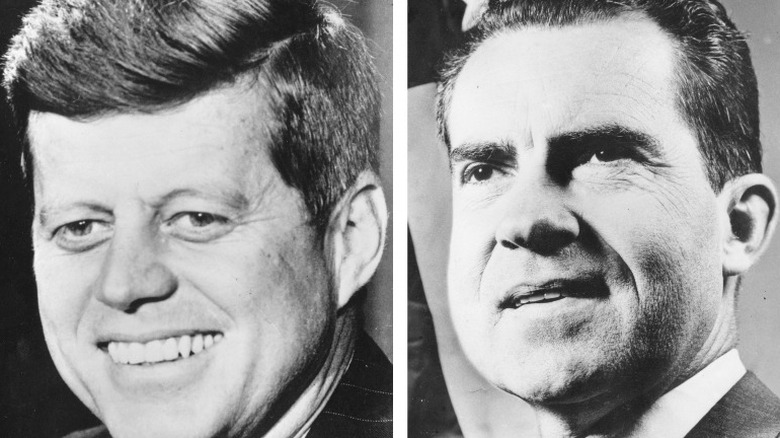

The first questionable incident with the Kennedy administration actually occurred before JFK was even president. One of the most pressing matters for United States foreign policy in the early 1960s was the Cuban Revolution and the ascension of Fidel Castro to power. On the 1960 campaign trail, the head of the CIA, Allen Dulles, gave a briefing to Kennedy on the current state of U.S. foreign policy. Dulles reportedly mentioned Cuba, but nothing specific about any covert plans for an invasion — which the Eisenhower administration was secretly planning with the CIA in what would become the Bay of Pigs invasion.

In their presidential debates, Kennedy's opponent Richard Nixon — the vice president at the time — accused Kennedy of being weak on fighting communism in Cuba. Kennedy responded by putting out a statement in The New York Times that specifically called for the Eisenhower administration to help indigenous Cuban forces trying to oust Castro. Nixon, claiming he was protecting the secret CIA operation's integrity, did not acknowledge the Eisenhower administration was already doing exactly that, and instead decried the idea.

Nixon was furious with Kennedy because he was convinced that JFK knew about the administration's planned secret operation and was trying to make Nixon look bad. Nixon blamed this flap for his eventual loss in the election; however, Dulles did not brief Kennedy about the Cuba operation, and Nixon was mistaken.

There have been claims the 1960 election was rigged

The 1960 presidential election was a remarkably close contest. While the electoral college result appeared to be a blowout — with John F. Kennedy winning 303 votes to Richard Nixon's 219 — the popular vote was much closer. The difference in the popular vote was barely 120,000 votes out of more than 68 million cast — or less than 0.5%.

Leading up to the election, the polls between Kennedy and Nixon were extremely close. Less than three months before, they were virtually tied in a Gallup poll, and on the eve of the election, they were within one percentage point of each other. Immediately after Kennedy's victory, however, there were claims of malfeasance, particularly in Illinois and Texas. The two states combined for 47 electoral college votes, which would have shifted the election to Nixon if he had taken both.

Accusations poured in against Democratic Chicago Mayor Richard Daley and Kennedy's running mate Lyndon B. Johnson, who was a Texas senator at the time. Nixon supporters claimed both states had engaged in ballot box stuffing and widespread voter fraud, and implicated them in "stealing" the election from Nixon. However, there has never been any reliable indication that voter fraud from either state was widespread or prominent, though historians argue as to whether or not some discrepancies occurred in Illinois. Nixon never formally challenged the results in Congress or court.

The massive failure at the Bay of Pigs

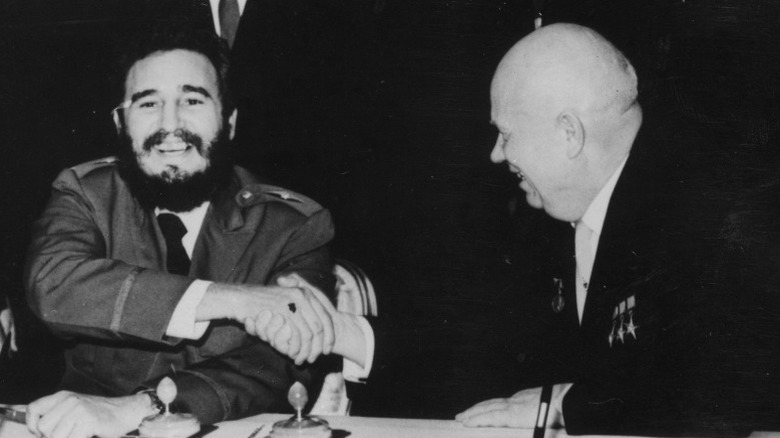

In 1959, Fidel Castro took power in Cuba. He was backed by a revolutionary army and quickly took control of the Cuban government. However, Castro soon drew the ire of Washington by drawing close to the Soviet Union's communist orbit, entering into contracts for Soviet oil, and publicly announcing their comradeship. The Eisenhower administration reacted to the socialist and communist overtures of Castro by approving a CIA operation to remove him from power. The plan was to recruit Cuban exiles who had fled to Miami after the revolution and train them into paramilitaries, before sending them back to the Bay of Pigs in Cuba to oust the Castro government and take control.

After John F. Kennedy became president, he authorized the operation to continue, and the Bay of Pigs invasion was a complete disaster. Over 100 U.S.-trained Cuban paramilitaries were killed by the Cuban Army, and nearly 1,200 were captured. Castro remained in power and an antagonist against the U.S. for decades, and the Kennedy administration was thoroughly embarrassed less than four months into the presidency.

Historians have laid much of the blame for the Bay of Pigs on decisions made by JFK. They mainly point to his insistence on starting the operation at night, his refusal to allow for a second round of bombing, and his refusal to allow the Navy to help the Cuban forces.

The CIA tried to assassinate Fidel Castro under JFK

After the Bay of Pigs invasion failed, the Kennedy administration was still looking to remove Fidel Castro from power in Cuba. Less than a year later, in January 1962, the Kennedy administration initiated "Operation Mongoose." Mongoose was a plot to remove Castro from power once and for all, and JFK's brother Robert Kennedy, the attorney general at the time, hand-picked legendary CIA agent Edward Lansdale to plan it.

However, Lansdale was not the only CIA agent working on the job. Another man, William Harvey, was also a senior operative at the CIA, and he started to work on the project after being assigned by the former head of the clandestine service, Richard Bissell. After struggling to make any headway for months, Harvey instead decided on a new tactic: using the mafia to assassinate Castro.

Harvey got in contact with mobsters Sam Giancana and Johnny Roselli, providing them with poison pills to give to Castro in Cuba, but they failed to carry out the hit. Another assassination attempt under the JFK administration was a failed plot to deliver Castro a scuba suit infected with fungi and tuberculosis bacilli. The suit was never delivered. After JFK's assassination in November 1963, the new president, Lyndon B. Johnson, gradually shut Mongoose down from May 1964 onward.

The dramatic escalation of the Vietnam War

One of the biggest foreign policy issues that JFK inherited from the Eisenhower administration was a growing financial and military commitment to the fledgling Republic of Vietnam. Previously, when he was a congressman in the House and Senate in the early 1960s, Kennedy had gone on record against any U.S. engagement in Vietnam. During the First Indochina War between the Viet Minh and the French, he called the prospect of U.S. military aid to the French "dangerously futile and self-destructive" (via Ronald E. Powaski's "The Cold War: The United States and the Soviet Union, 1917-1991").

However, by the time he was on the campaign trail in 1960, Kennedy was singing a different tune. Worried about Chinese Premier Mao Zedong's growing communist influence in Asia, JFK now favored much more aggressive tactics in Vietnam. He initiated a counterinsurgency strategy to combat the Viet Cong's use of guerrilla warfare and started to allow the direct participation of U.S. soldiers in combat against the communists.

When Eisenhower left office in January 1961, there were only 700 advisors in the country. Yet, within four months on the job, JFK had sent another 500 Special Forces troops and military personnel to Vietnam, and within two years, he sent another 10,000 advisors on the way. By the time JFK was assassinated, there were roughly 16,700 U.S. advisors in the country, 16,000 more than in 1960, with events swiftly escalating.

JFK supported the assassination of Ngo Dinh Diem

While the conflict in Vietnam was escalating during 1963, some of the most cataclysmic events of the entire war took place. That spring, CIA agent Lucien Conein had gone into South Vietnam to spy undercover. In May, he went to the former provincial capital of Hue to see the celebrations surrounding the Buddha's 2,527th birthday. However, while the celebrations were taking place, South Vietnamese soldiers and police officers killed and assaulted several Buddhist worshippers.

In protest, one Buddhist Monk, Quang Duc, doused himself in gasoline and immolated his body in front of the entire world. However, South Vietnamese President Ngo Dinh Diem (pictured above) continued to escalate his government's war on the Buddhists, and his forces started to openly kill women and children in their pagodas. Soon, the Kennedy administration began to secretly discuss plans to remove Diem from power.

In late August, Kennedy approved a cable recommending action, and on the 26th, the Ambassador to South Vietnam cabled back to Kennedy that "We are launched on a course from which there is no turning back: the overthrow of the Diem government" (via Tim Weiner's "Legacy of Ashes: The History of the CIA"). Vietnamese generals assassinated Diem in early November, with $40,000 in backing from the CIA. Kennedy regretted the decision in the aftermath, immediately expressing dismay and disgust. However, without his support, it likely would not have happened in the first place.

His administration's use of the CIA

When John Kennedy took over the presidency from Dwight Eisenhower, he initiated quite a change in the CIA. It took some time, at least initially, because he was so upset with them over their handling of the Bay of Pigs crisis that he wanted nothing more to do with them. However, he quickly changed his mind and started to supercharge their activities.

Whereas Eisenhower's administration had launched about 170 CIA operations during the entire two-term presidency, Kennedy initiated nearly as many — 163 — in less than one term. This meant the CIA was conducting operations at double the rate under Kennedy compared to Eisenhower, including the aforementioned plots against Fidel Castro.

Much of this was carried out under the supervision of John McCone, who took over as the director of the CIA after Allen Dulles departed following the Bay of Pigs disaster. Initially, JFK considered putting in his brother Robert Kennedy as the director, but thought better of it and chose McCone, a former Eisenhower appointee, instead. Not only did the CIA authorize 163 missions during JFK's tenure, but they had plans approved for nearly 400 more. Indeed, the Kennedy administration continued to pressure the CIA for increased covert missions.

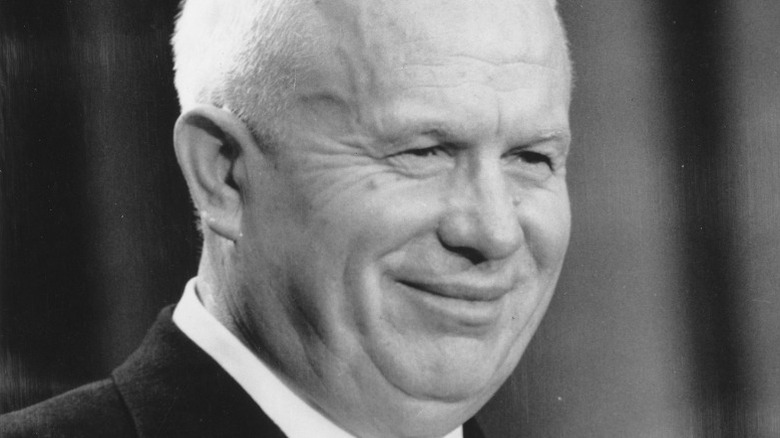

JFK's embarrassing summit with Nikita Khrushchev

The first six months of John Kennedy's presidency were about as dreadful as you can get. First, election-rigging accusations clouded his initial victory, then he presided over the disastrous Bay of Pigs invasion in April. A month and a half later, in June 1961, at his first summit with the Premier of the Soviet Union, Nikita Khrushchev, things again went poorly. Khrushchev, who was 67 at the time and had been a Bolshevik since the Russian Revolution, did not respect the 44-year-old Kennedy or take him seriously.

Khrushchev compared JFK negatively to his predecessor, Dwight Eisenhower, and considered him immature. Kennedy, eager to prove himself to the veteran hard-line communist, tried to debate Khrushchev on issues like Marxism and imperialism, but that only served to prove his own ineptitude and inexperience.

At one point, Kennedy even told Khrushchev he considered there to be rough parity between the Western European forces, like NATO, and the Sino-Soviet Alliance in Asia. Kennedy's aides were shocked that he would make such an assertion, while Khrushchev was thrilled with getting an American president to actually admit he considered the USSR military equals. After the summit, Kennedy knew he was a beaten man. He referred to the meetings with Khrushchev as the "Worst thing in my life," remarking that "he savaged me" (via The New York Times).

The Berlin Crisis

When WWII ended, one of the biggest questions for the Allies was how to administer newly occupied Germany. They decided to split the country into four zones, with a victorious ally — the United States, France, Great Britain, and the Soviet Union — each taking responsibility for one zone. The Soviets also wanted the other allies to vacate Berlin, which was in the Soviet sector, and tensions increased when the West balked.

In November 1958, Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev gave a speech demanding the Western allies immediately leave Berlin and pull out all of their personnel and equipment within six months. However, negotiations between Khrushchev and the Eisenhower administration broke down over the U-2 spy plane scandal in 1960, and Khrushchev decided to wait for the next presidential administration before renewing talks. At the Vienna Summit with Kennedy in 1961, the Soviet leader again gave the U.S. six months to leave Berlin. Kennedy responded by sending 1,500 troops to the German capital via the Autobahn and called up 150,000 army reservists.

Then, on August 13, 1961, the East German government started to erect the now infamous Berlin Wall, separating East and West Berlin. Eventually, the wall became reinforced with concrete and stood as a symbol of the Cold War until its destruction in 1989.

The Checkpoint Charlie standoff

After the erection of the Berlin Wall in August 1961, tensions started to seriously boil between the United States and the Soviet Union. Later in the month, in response to the Kennedy administration's continued buildup of nuclear weapons, Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev publicly announced the resumption of open-air nuclear weapons testing, ending a two-and-a-half-year moratorium. They conducted nearly a nuclear test a day for the next two months, including exploding the Tsar Bomba, the largest nuclear explosion to ever be recorded. That September, Kennedy responded by resuming the U.S.'s dormant nuclear testing program.

Back in Berlin, temperatures were getting even hotter. In late October, at Checkpoint Charlie — one of the authorized crossing areas of the Soviet-U.S. border in Berlin, Germany — a dispute broke out over the search of U.S. diplomats and their travel documents. The Kennedy administration responded by mobilizing several U.S. Army tanks to face their gun barrels towards the East German side.

The Soviets responded by stationing their own tanks to face directly at the U.S. tanks, and everyone was locked and loaded, waiting for a confrontation. Thankfully, however, cooler heads prevailed. Kennedy reached out to Khrushchev through secret back channels, and the two agreed to both remove their tanks from Checkpoint Charlie, ending the threat of escalation.

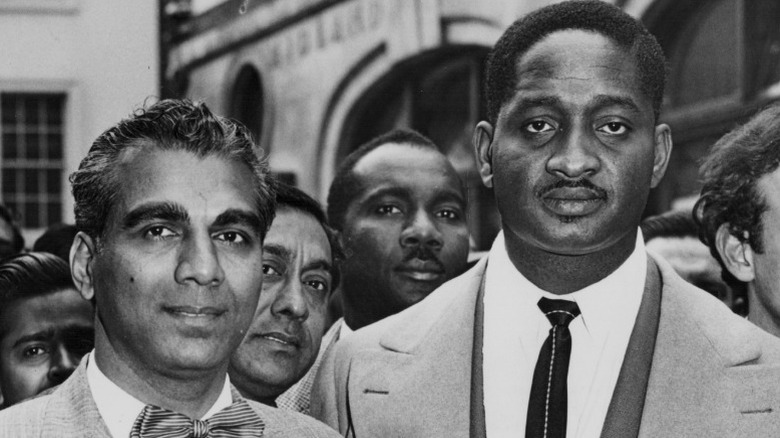

JFK initiated the overthrow of Guyanese leader Cheddi Jagan

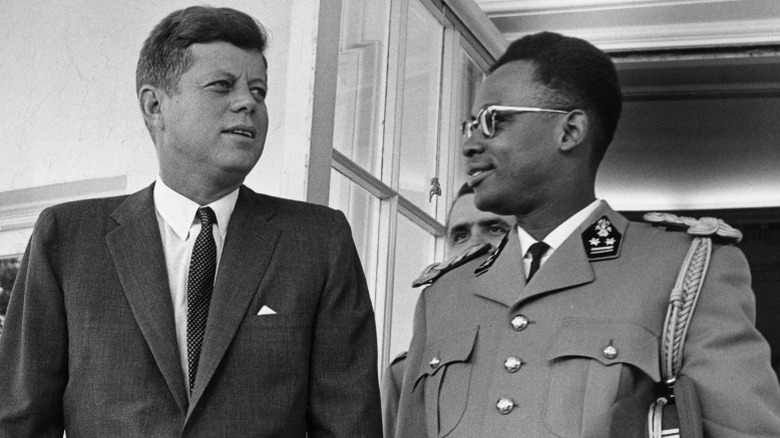

In August of 1962, President John Kennedy's attention was focused on British Guiana, a small country in northern South America. Guiana had been under the control of Great Britain since the late 18th century and had only recently been allowed just nominal independence. However, when the British allowed open elections for the first time in the 1950s, the winner, Cheddi Jagan (pictured above left), was immediately labeled a communist and thrown in jail.

He was released a year later, and in the 1961 elections, Jagan's political party won 75% of the seats in the Guyanese assembly, and he was elected as the new Prime Minister. Almost immediately, Kennedy and the Director of the CIA, John McCone, started to discuss possibilities for removing Jagan from office due to his perceived communist leanings. Jagan visited the White House that October and tried to convince Washington that he was not aligned with the Soviet Union. However, JFK refused to listen, and instead, he initiated a $2 million program for Jagan's overthrow the following August.

Throughout 1963 the CIA started to put their backing behind Jagan's political opponent, Forbes Burnham (pictured above right). Kennedy was assassinated in November 1963 before any action happened, but the CIA, with British support, was able to push Jagan from power in 1964 under JFK's successor Lyndon B. Johnson.

His failed Alliance for Progress

When JFK became president in January 1961, the issue of communism in Latin America instantly became one of his top priorities. The recent ascensions of Fidel Castro and Cheddi Jagan to power in Latin American countries showed that communism had spread to the western hemisphere, and Kennedy was determined to stop it from spreading. As such, in mid-March 1961, Kennedy announced the creation of the Alliance for Progress in Latin America. The purpose of the alliance was to fight against inequality and poverty in Latin America by creating programs to help diminish the amount of illiteracy and improve public health.

That August, Kennedy and his wife Jaqueline traveled to Uruguay to inaugurate the Alliance for Progress in Punta del Este. Unfortunately, the Alliance was hampered from the beginning. Federal funding, originally pledged at $10 billion over 10 years, was partly spent on creating paramilitary armies to fight communism, and never reached even close to the levels of the Marshall Plan in Europe.

Though there were some mild improvements to housing, education, and public health, overall, the Alliance was a disaster. Economic growth slumped below anticipated levels, unemployment increased, and no less than six military coups occurred in Latin America during Kennedy's presidency. Rapid population growth mitigated many of the improvements made to poverty and public health, and most Latin American leaders feared Washington far more than they did communism.

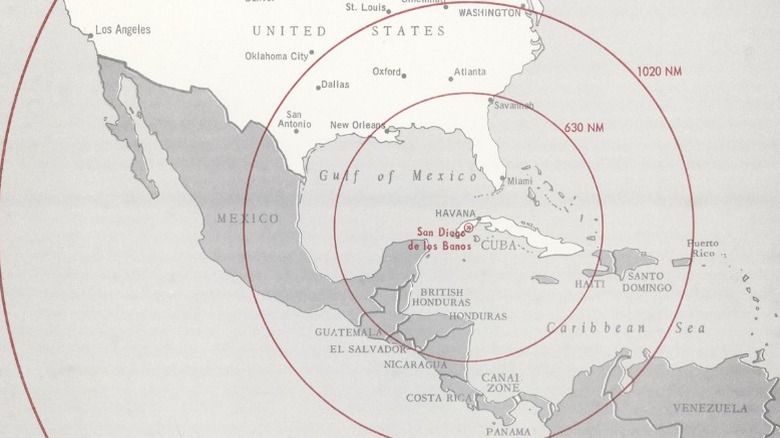

His initial handling of the Cuban Missile Crisis

For many Americans living during the Cold War, the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis was one of the scariest points of their entire lives. That October, the Kennedy administration announced they had discovered the Soviet Union was moving nuclear missiles onto the island of Cuba, barely 90 miles away from the coast of Florida.

In response, Kennedy immediately instituted a blockade around Cuba and issued an ultimatum: remove the missiles or risk nuclear war. When a U.S. reconnaissance plane was shot down over Cuba on October 27, war seemed inevitable. However, at the last minute, Kennedy and Nikita Khrushchev agreed on a compromise to remove the weapons, and war was avoided. Normally, JFK gets very high marks for his handling of the crisis, but what most people do not realize is that the Kennedy administration actually had information about the nuclear weapons a month and a half earlier.

JFK first became aware of the sites after a spy plane photographed them on August 29. Yet when informed, he told his aides to bury the report because he was worried about a scandal so close to the midterm elections. After a U-2 spy plane was downed over China weeks later, Kennedy grounded all U-2 flights over Cuba, and the Soviets moved 99 nuclear missiles in on October 4 without the U.S. knowing. When U-2 flights restarted, the missiles were revealed, kicking off the crisis.

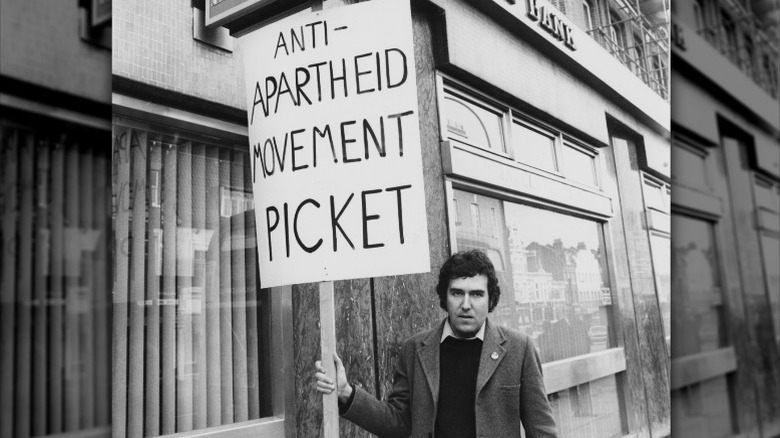

His lax foreign policy on apartheid in South Africa

While JFK certainly had his hands full dealing with problems in Latin America, his policies towards Africa offered him little respite. While campaigning against Vice President Richard Nixon in 1960, Kennedy criticized the Eisenhower administration's attitude towards Africa. However, when he took over in early 1961, there was a strong continuity between the two administration's Africa policies.

Kennedy was just as concerned with the rise and spread of communism in Africa as he was in Vietnam, especially after the Soviet Union started to gain a foothold in the northeast. Kennedy began to offer financial incentives to neutral African leaders to get them to ally with the U.S. over the Soviet Union, but did little to champion true African nationalism and independence.

His policies in South Africa were even worse. Apartheid and segregation had been endemic in the country since the early 20th century, and in the 1950s, they were enshrined into law by the racist Afrikaner government. The Kennedy administration did basically nothing to end Afrikaner rule in South Africa and only engaged in symbolic efforts to protest the domination of white supremacy. He refused to back any economic sanctions and continued to be reliant on the country's precious minerals for trade. JFK did finally acquiesce to signing an arms embargo against them, but he also continued to sell them spare military parts — effectively undermining it.

JFK's relationship with Mobutu Sese Seko

Another area of Africa that drew the close attention of the Kennedy administration was the "Congo Crisis," which had actually begun during the previous administration in 1960. Throughout 1960, the Congolese were preparing for their official independence from Belgium, to the high hopes of the Eisenhower administration. However, that June, a mutiny broke out, pitting Congolese and Belgian troops against each other, and soon the entire country was engulfed in chaos.

In the midst of infighting in the new Congolese government, a colonel in the army, Joseph Mobutu (pictured above), initiated a coup d'etat and seized power. The new Kennedy administration immediately supported Mobutu and his bid to create a stable and pro-Western Congo, gave him huge funds, and signed bilateral military agreements. Kennedy even arranged for Mobutu to attend parachute training school at Fort Benning, Georgia, as a testament to their relationship.

Mobutu, who renamed Congo to Zaire and started to call himself Mobuto Sese Seko, ruled the country for the next three decades until being deposed in 1997. His government was incredibly unstable, and he constantly faced attempted coups and rebellions. He is also noted for his corruption, gaining a massive personal fortune while presiding over an endemically poor and economically stagnant country. Yet, without Kennedy's support, he might never have gained power in the 1960s.

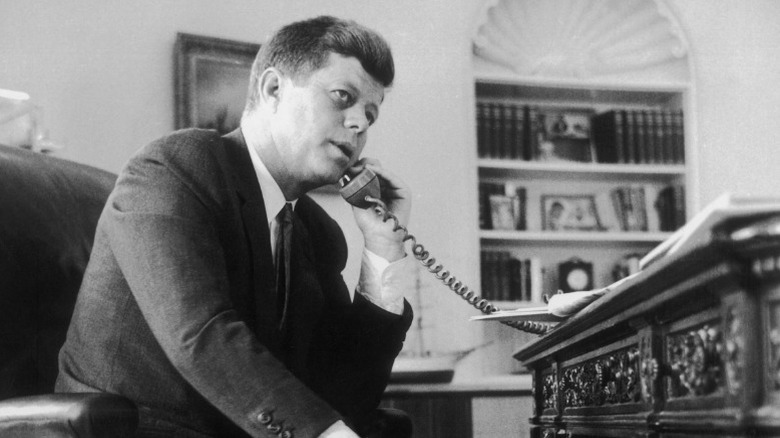

His secret recording system in the White House

It might sound surprising at first, but from Franklin D. Roosevelt in the 1930s all the way to Richard Nixon in the 1970s, every single American president had at some point allowed for secret recordings of their meetings. During his time in office, John Kennedy was one of the most prolific secret tapers of all. In the spring of 1962, Secret Service agent Robert Bouck installed JFK's secret recording system in both the Oval Office and Cabinet Room.

JFK died before ever having to answer about the secret taping system, which was only publicly revealed in 1973 during the hearings on the Watergate scandal. His secretary, Evelyn Lincoln, has suggested that it was possibly installed for the innocent purpose of keeping accurate records. She also proposed that Kennedy had it put in because his advisors had previously agreed to things in private only to publicly claim the opposite, and JFK wanted to be able to hold them accountable.

Regardless of the reason, Kennedy and various Secret Service agents were the only ones with access to the taping systems, which were controlled by hidden secret switches. There were microphones located in multiple places to make sure as much was recorded as possible. Kennedy racked up nearly 250 hours of taped meetings and 12 hours of recorded phone calls from early 1962 until his death in November 1963, much of which has now been declassified.

Rumors of infidelity

Ever since he was assassinated on November 22, 1963, JFK's legacy has constantly been subjected to incredibly sensationalized rumors about his private life. The most notorious among them are his alleged affairs with several mistresses. JFK is suspected of being involved in at least six affairs, and several of them were supposedly with White House staff, including interns and secretaries. Many of the women have claimed the relationships started in the late 1950s or 1960s, when Kennedy would have been either a senator or the president.

Unfortunately, there is not a ton of evidence to support whether or not most, or any, of these affairs ever actually happened. JFK was never given an opportunity to confront his accusers before his death, leaving open the possibility of whether he would have ever confirmed them or not. However, several Kennedy aides, like Barbara Gamarekian, have validated some suspicions of his various infidelities.

The most famous accusation revolves around an alleged affair he had with actress and superstar Marilyn Monroe in the 1960s. There is also some speculation that his wife, Jaqueline Kennedy, knew about the affairs but tolerated them. Unfortunately, it is likely we will never know the complete truth about Kennedy's private life and whether or not he really had as many affairs as he is accused of.

Rumors about ties to the mob

Another area of John Kennedy's private life that is rife with speculation is his and his family's alleged ties to mob figures like Sam Giancana and the Chicago Outfit. The rumors go back to the 1960 presidential election, with its accompanying accusations surrounding ballot stuffing and widespread voter fraud. There are allegations that Kennedy's father contacted Giancana about having the Chicago mob rig the election in his son's favor, in exchange for not prosecuting their various crimes once in office. There are also allegations that Frank Sinatra contacted Giancana on behalf of Kennedy to flip the election for his son. However, none of these allegations have any evidence to support them.

The biggest accusations to connect Kennedy and the mob were made by Judith Campbell Exner in her memoirs. Exner wrote (via The Irish Times) that she had affairs with both Giancana and Kennedy, and that she had tried to introduce them to each other in 1960 to help fix the election. However, her stories at times contradicted each other and were vehemently denied by Kennedy's closest aides.

It is true that Kennedy's CIA and Giancana were working together to assassinate Cuban President Fidel Castro. Yet, it was not arranged personally by Kennedy himself, but rather by CIA agents Richard Helms and William Harvey — though Kennedy may have been aware through his brother Robert.

Kennedy installed friends and family in lofty positions

In American presidential elections, to the victor go the spoils, which means appointing virtually anyone the newly inaugurated head of state wants to lofty positions of power. To take the job requires approval of Congress, and in 1961, President John F. Kennedy nominated for attorney general the man who'd managed his 1952 U.S. Senate campaign and 1960 presidential campaign: Robert Kennedy, who also happened to be his brother.

Essentially the chief federal legal official, the attorney general is usually someone with extensive experience as an attorney or judge. Attorney General Kennedy had served as counsel to a few Senate subcommittees in the 1950s, but didn't have much of a resume, and got the job as a benefit of nepotism. President Kennedy didn't only reject criticism of his decision, he mocked it. At a dinner party in February 1961, he remarked of his brother (via Time), "I can't see that it's wrong to give him a little legal experience before he goes out to practice law."

Following the election of Kennedy, David Ormsby-Gore was appointed the U.K.'s ambassador to the United States. A member of Parliament and the 5th Baron Harlech, he was related to Kennedy and a friend of the family, dating back to presidential father Joseph Kennedy's stint as the U.S. ambassador to the U.K. A frequent casual and professional guest at the White House, the British national and future member of the House of Lords helped draft Kennedy's foreign policy positions.

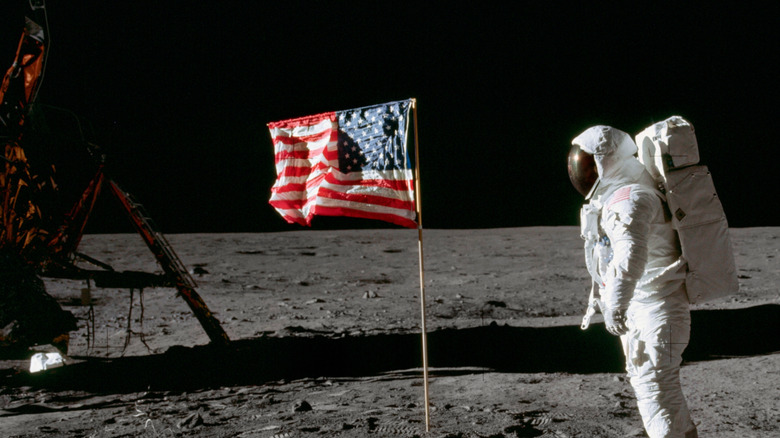

His moonshot was wildly unpopular

On May 25, 1961, President John F. Kennedy delivered a "Special Message to Congress on Urgent National Needs." The pressing matter Kennedy wished to discuss was the U.S. space program. "First, I believe that this nation should commit itself to achieving the goal, before this decade is out, of landing a man on the moon and returning him safely to the earth," President Kennedy said during his address (via the JFK Library). That mission was actually already underway, as Project Apollo started up at NASA in 1960. The program ran until 1973 and peaked with multiple moonshots that placed American astronauts on Earth's natural satellite, including the historic and pioneering Apollo 11 flight in July 1969, at a total cost to American taxpayers of $28 billion.

Kennedy's hyper-focused mission wasn't just about human progress or scientific achievement; getting a man on the moon and back was political theater. The U.S. was engaged in a space race with the Soviet Union, and it was important from an international relations standpoint that a democratic and capitalist nation got to the moon before the communist Russians did. However, during the Kennedy administration there was major public pushback to going to the moon.

Academics resented how the entire scientific community was co-opted into a political project, while pundits and regular citizens resented spending so much money, and military funding, on what looked like a fantasy. In 1961, a Gallup poll indicated a paltry 33% public support for heading to the moon.

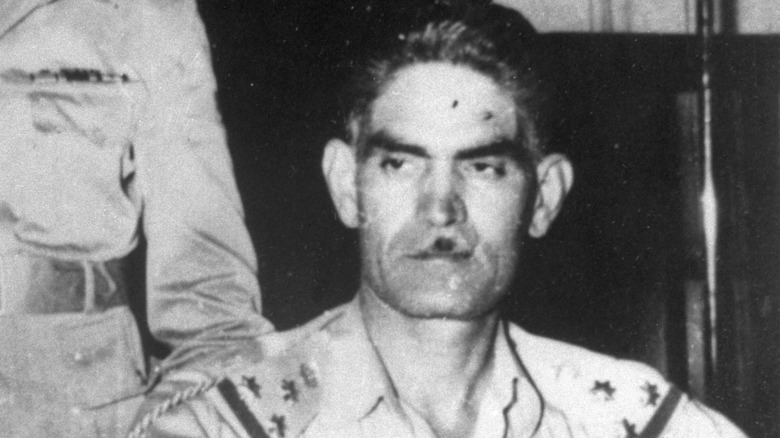

He supported a coup in Iraq

The United States is a superpower, politically and economically, and its various covert and military-aligned agencies have been accused of forcing its hand on the operations of other independent and sovereign nations. During the Cold War, for example, the U.S. State Department quietly supported and encouraged coups that destabilized unfavorable governments or economic systems — like the communist Soviet Union — in favor of ones with a pro-democratic stance that could be more easily manipulated by American interests. In 1963, the two-day-long Ramadan Revolution resulted in Prime Minister Abd al-Karim Qasim of Iraq (pictured above), who had socialist and communist leanings and a close relationship with Soviet officials, being ousted and executed by the militant division of the Middle Eastern nation's Ba'ath Party.

The Ramadan Revolution happened with substantial support from the U.S.'s chief spy agency, the Central Intelligence Agency. It helped stage and fund the bloody coup in Iraq, and it was all authorized by the John K. Kennedy administration. Getting rid of an old regime in favor of a pro-U.S. one aligned with Kennedy's strategy for dealing with the Middle East and the threat of the spread of communism.

Kennedy was secretly extremely unhealthy

Outwardly and publicly, John F. Kennedy embodied the very image of health and strength. Footage of the president playing sports was widely circulated, contributing to the idea that the youngest elected president in history — just 43 when he took the oath of office — was full of youth and vigor. Privately, however, the president was quite ill, and chronically so, as well as extremely medicated. This dark secret was hidden by the Kennedy family, and only revealed decades after Kennedy's death.

Among Kennedy's numerous diagnosed medical conditions are: colitis, an inflammation of the large intestine that causes intense pain in the abdomen and diarrhea; prostatitis, or an inflammation of the prostate that causes pain in the pelvis and urinary difficulty, and Addison's disease, a double hormone deficiency that manifests in serious fatigue, blood sugar issues, and pain throughout organs, muscles, and joins.

Kennedy also had osteoporosis specific to his lower back so severe that he adjusted his daily movements to manage the pain. Kennedy regularly took 12 prescription medications during his presidency to manage all of his medical conditions. The president ingested with frequency strong painkillers like methadone, codeine, and Demerol, as well as a cocktail of stimulants, sleep aids, anti-anxiety meds, a thyroid regulator, and injections of the anti-infection drug gamma globulin. He'd also occasionally need steroids for the Addison's disease, anti-spasmodics to treat colitis, and an anti-psychotic supposedly to counter the side effects of one of the other medications.

He weaponized audits

As one of his first acts after assuming the office of attorney general in 1961, presidential brother Robert Kennedy and Walter Reuther (then the president of the United Auto Workers labor union) drafted the "Reuther Memorandum." One tenet drawn up was a plan to adhere to the Federal Communication Commission's infrequently enforced rule to provide equal time to different political viewpoints, which would limit and counter right-wing and Republican speech on American television and radio.

The other main action proposed was "The Ideological Organizations Audit Project," with which Attorney General Kennedy and Reuther sought to use the Internal Revenue Service to thoroughly investigate just how conservative nonprofit organizations used their funds, and if anything could call into question their tax-exempt status. Not only did President John F. Kennedy approve of the program, a highly partisan use of government resources to go after political opponents of the chief executive's Democratic Party, but it was also partially his idea.

"The program was stimulated by a public statement by President John F. Kennedy and also a suggestion by Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy," the Congressional Joint Committee of Taxation said in a 1973 report (via Tax Notes). Then-IRS Commissioner Mortimer Caplin revealed that he'd personally received calls from President Kennedy or one of his chief advisors to check in on conservative organizations' financial affairs.

He authorized spying on Martin Luther King

One of the chief aims of the presidency of John F. Kennedy was to advance the Civil Rights Movement. Started in earnest in the 1950s with the federally ordered desegregation of schools alongside widespread protests and demonstrations, the drive to ensure equal rights and treatment for all Americans, particularly Black Americans, was explicitly supported by President Kennedy. "This nation, for all its hopes and all its boasts, will not be fully free until all its citizens are free," Kennedy said at a speech in June 1963 (per the National Park Service).

Despite his public advocacy and urging for the release of civil rights leader Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. from a Georgia jail, after a protest just before the 1960 election, Kennedy hesitated to push for definitive civil rights legislation because he didn't want to lose the help of segregationist Democrats in Congress. Kennedy also secretly kept an eye on King.

In 1969, the FBI disclosed that while he was president, Kennedy had authorized federal agencies to spy on the leader via a telephone wiretap of King's home phone and his office at the Southern Christian Leadership Conference in Atlanta. Attorney General Robert Kennedy signed off on the plan, and the surveillance began two weeks before the presidential assassination. The reason: Kennedy had received intel that one of King's lieutenants, Stanley Levison, was covertly a Communist.

The Kennedy administration approved a robbery of the French embassy

When the National Security Archive was ordered in 2025 to release any and all remaining secret files relating to the early 1960s presidency of John F. Kennedy, that unsealed "Family Jewels," a 693-page report pertaining to the Federal Bureau of Intelligence's investigation into years of possible overstepping and power abuses by the Central Intelligence Agency. Some passages reveal just how much the deceased commander-in-chief knew about potentially illegal or untoward CIA projects, many of them secret and sensitive.

In 1962, for example, CIA officials provided in-person briefs to both President John F. Kennedy and Attorney General Robert Kennedy, regarding an issue with France. Agents believed that the French embassy in Washington, D.C., had documents on its grounds that would be useful for counterintelligence, and that they should be covertly obtained. With the blessing of both Kennedys, the mission was executed, and the covert documents were indeed obtained. Robert Kennedy went so far as to tell the CIA to not inform the FBI of the plan, which constituted breaking and entering and burglary.

He acted out against reporters he villainized

At press conferences, President John F. Kennedy displayed a casual and friendly rapport with reporters. He liked the media if it did right by him, but if reporters were to cross him or portray his administration in a disparaging light, he'd retaliate. In 1962, Kennedy tried and failed to stop CBS and NBC (twice) from running critical news specials. Also in 1962, the New York Times' military reporter Hanson Baldwin published a piece detailing how the Soviet Union had added extra protection to its nuclear missile silos should the U.S. ever launch a strike, which American authorities discovered with cutting-edge image-gathering technology — spying, in other words. That was all sensitive, classified information, and it had been leaked. President Kennedy's office demanded to find the source, and so federal officials started tapping phones, monitoring Baldwin's calls and those of a secretary at The New York Times' office in Washington, D.C. In early 1963, the president authorized and ordered phone tracing on columnists Robert S. Allen and Paul Scott, after they each published information that was supposed to be classified.

Kennedy's role in crushing the media on multiple occasions was discovered after the surfacing of secret tapes of meetings. Cohorts of the president didn't know at the time that their conversations were being recorded by Kennedy's furtive taping system, a legally dubious bit of record-keeping.

Kennedy dropped poison over Vietnam

President Kennedy inherited the Vietnam War from his predecessor, Dwight Eisenhower. Preventing the anti-colonial Viet Cong forces of Ho Chi Minh, aligned at least politically with the communist superpowers of the Soviet Union and China, was part of a broader foreign policy in the Cold War stance of the U.S, to prevent communism from taking root in Southeast Asia. In late 1963, weeks before his death, Kennedy considered pulling back on American involvement in the region, planning to remove as many as 100,000 troops from the split Vietnam area. But during his presidency, he also actively escalated the war, allowing for the introduction of new and devastating weapons.

Initially proposed by U.S.-supported South Vietnam's president, Ngo Dinh Diem (pictured above), the U.S. military put "Operation Ranch Hand" into effect in January 1962. U.S. Air Force planes were outfitted with large volumes of herbicides, which were systematically dropped across South Vietnam to destroy large swaths of vegetation that the Viet Cong could otherwise have used to feed itself (and the citizens of Vietnam) and to use as cover for its attacks on U.S. and South Vietnamese troops.

It was, in essence, a form of chemical warfare, and it occurred in secret. President Kennedy authorized Operation Ranch Hand in November 1961, but as a tentative, limited-time idea. Instead, the project quickly grew and lasted nine years, devastating the jungles and mangrove forests of South Vietnam with 18 million gallons of toxic chemicals.