Medical Mysteries That Changed Everything We Knew

Not so very long ago, doctors thought disease was caused by an imbalance of "humors," which consisted of two different disgusting types of bile, the stuff that collects in the back or your throat when you have a cold, and blood. Oh and everything could be cured with leeches. Today we know better, mostly. The medical mysteries of the past are the vaccinations, sanitations, and food pyramids of the present. Here's a short list of some of the medical mysteries that changed everything.

The spread of cholera

Cholera first arrived in the England in 1831, during a time when people dumped their poop into big, open pits or directly into the Thames. Entrepreneurs also had the brilliant idea to take water out of the Thames, bottle it, and deliver it to the local pub — sort of like the clear, mountain spring water we can buy in bottles today but without the clear part, the mountain part, or the spring part.

People all over London were ordering glasses of poop water with their fish and chips, yet it was somehow a great mystery why everyone started getting sick with cholera. By 1854, tens of thousands of people had been struck by the mysterious and violent illness, which most people believed was spread by "miasma" or "bad atmosphere." Because that sounds way more plausible than poop water. Anyway, according to the UCLA Department of Epidemiology, there was just one doctor — a man named John Snow — who thought the cause might be contaminated water. Snow used a highly advanced method of geographical charts to map the spread of the disease in the London suburb of Soho, and extensive interviews with the families of people who died from the illness to prove that the source was the Broad Street pump, a communal well where hundreds of people got their water. Snow convinced town officials to disable the pump, and new cases of cholera dried up almost overnight, thus proving that at least one John Snow knew something.

Pellagra

After Columbus got back from the "New World" and finished bragging about how awesome he was for discovering a land that already had 112 million people living in it, he presented to the world a brand-new cereal crop: corn. Corn was cheap and had higher yields than other cereal crops like barley and wheat, so it quickly replaced staple crops throughout Europe, Africa, and Asia. Then, people started getting sick with a mysterious illness called "pellagra" or "sour skin disease."

According to the European Food Information Council, pellagra sufferers developed a nasty disposition and inflamed skin that was sensitive to sunlight, which some historians think might have contributed to vampire mythology. They also went on to develop severe dementia and would usually die within four or five years.

It wasn't until 1735 that someone made the connection between corn and pellagra, but most scientists believed corn contained some kind of toxin that caused the illness. Weirdly, people in Mexico didn't seem to suffer from pellagra at all, despite the fact that they ate as much corn as the rest of the world.

Still, another 175 years or so passed before researchers found the answer: Mexican chefs would soften the corn in an alkaline solution, which made the niacin in the plant bio-available. In other words, people in Mexico were getting the important nutrient niacin from corn, and people in the rest of the world were not. Pellagra, as it turned out, was a nutritional deficiency.

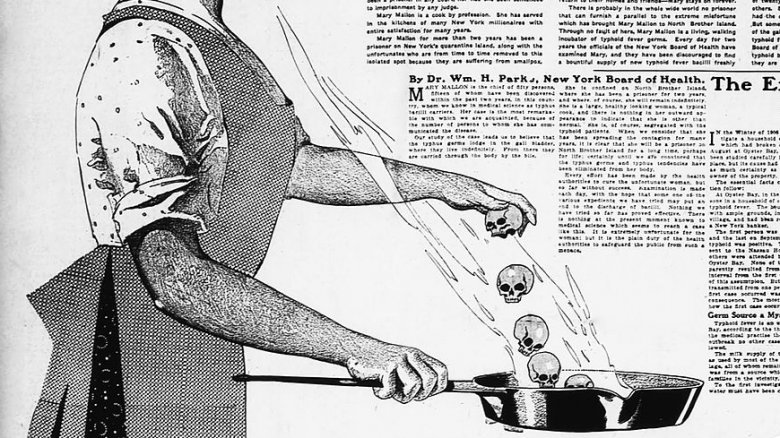

Typhoid Mary

In the early part of the 20th century, six members of a wealthy New York family fell ill with typhoid fever. This was way more appalling than when poor people got typhoid because typhoid was considered a disease of the ghetto. Clearly, something had to be done.

According to History, the family hired a "freelance sanitary engineer" to investigate, who discovered that Mary Mallon, the family's cook, seemed to have a mysterious link to the disease — at least seven of the families she'd cooked for had had bouts with the dreaded illness.

Now, typhoid is spread though that most charming of transmission modes, the "fecal-oral route," which means you get it when you eat food prepared by someone who didn't bother to wash her hands after she pooped. The good news is that high temperatures can kill the bacteria that cause typhoid. The bad news is that Mary Mallon's specialty was peach ice cream. With poop sprinkles.

It wasn't until 2013 that anyone finally cracked the mystery as to how Mallon (and other asymptomatic carriers) were able to transmit the disease without becoming ill. Researchers believe the bacteria seek out the less-aggressive macrophages (the cells that attack pathogens) that typically only start working during the later stages of an illness. Then, they hack the genetic programming of the cell and take over. The person remains healthy, serves up some poop sprinkles, and everyone else gets sick. Nature is a beautiful thing.

Chimeras

In 2002, Lydia Fairchild applied for public assistance. As a part of the application process, her boyfriend had to take a paternity test to prove he was the father of her two children. Business Insider reports that the routine test revealed something shocking — Fairchild's boyfriend was indeed the father, but Fairchild was not the mother.

The state, no doubt giddy with delight, believed they'd undone an attempt at welfare fraud. When Fairchild denied that she'd kidnapped someone else's children or was using random kids as a means to collect a check, the state decided to monitor the birth of her third child and thus prove their case. To everyone's great dismay, Fairchild gave birth to yet another baby that could not possibly have been her genetic offspring.

What in the heck was going on? Prosecutors searched medical history to find the answer, and discovered a similar case in which a woman seeking a kidney transplant was found to not be the genetic mother of the two children she'd given birth to. After a series of medical tests, doctors discovered that she was a chimera, or a person who carries two completely different DNA blueprints in a single body. Remarkably, a person becomes a chimera in utero, when two individual fertilized eggs fuse into a single egg containing two sets of genetic material. So biologically, that means that Fairchild is two people. How's that for an episode of House.

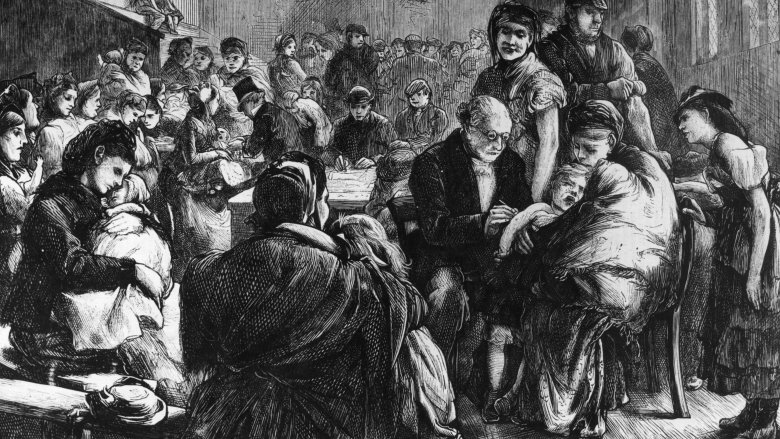

Vienna's General Hospital maternity wards

In 1846, Vienna's General Hospital had two maternity wards. Sometimes women would give birth in the street to avoid going to the first one, where the rate of fatal puerperal fever was nearly triple what it was in the second.

According to New York Magazine, doctors were baffled until a physician named Ignaz Semmelweis wondered if it might be bad that doctors in the first ward were performing autopsies and then immediately going upstairs to deliver babies with blood and fluids all over their hands. Because for some reason it never occurred to anyone else how freaking disgusting it is to walk around with dead person particles all over your hands, even before you get to actually delivering babies that way.

Semmelweis ordered doctors to start washing their hands in a disinfectant solution, which was effective at eliminating "the putrid smell of dead tissue" and also implies that physicians not only had disgusting hands but also reeked like corpses. So it's no wonder, really, that women would rather give birth in the street than go to maternity ward number one.

Semmelweis's new rule cut the death rate by 90 percent, but doctors elsewhere in Europe got all butt-hurt at the implication that they were killing their patients and went on not washing their hands anyway. So ultimately, Semmelweis failed to convince anyone what we know is true today: that doctors should not deliver babies while stinking like a decomposing corpse.

Acronizing chickens

All sorts of technological wonders hit the store shelves in the 1950s, from the first diet soft drink to the first Barbie doll. Women's magazines were full of miracle products, like this one: a "revolutionary process" which produced crisp-skinned chickens that were "wholesome" and "country sweet," whatever that means. Like chocolate chip cookie sweet? Peach ice cream? Sounds disgusting, but let's move on.

According to NPR, the process touted in women's magazines was "acronizing," which basically just meant dipping dead chickens in an antibiotic solution to keep decomposition at bay, making it possible to sell said chickens weeks after they'd been slaughtered. Yum. Shortly after the factories introduced this technological miracle, working-class men started showing up in medical practices with angry red rashes and boils all up and down their arms. They were suffering from classic staph infections, but it was the sort of infection that tended to spread in hospitals, not as much in the outside world. None of the men had a doctor or hospital in common, but they did share the same workplace: that's right, a poultry processing plant that had recently introduced the technological wonder of acronizing.

In what was one of the first examples of antibiotic resistance, live chickens were given antibiotics, the staph bacteria that infected them was developing resistance, and those resistant bacteria were able to survive the antibiotic bath. So the workers were sticking their hands and arms in water that was essentially teeming with super-staph. Nice.

Smallpox-immune milkmaids

Smallpox was one of the most terrifying diseases of the pre-modern era. It killed relentlessly, and it deeply scarred anyone lucky enough to survive. According to the Telegraph, one of the earliest forms of inoculation, called "variolation," was introduced to combat the spread of smallpox in 1717. Variolation was a pretty word for a disgusting practice: drawing pus out of some random person's pox and injecting it under the skin of a healthy person. The procedure usually caused a mild case of smallpox and was just as contagious as a bona-fide case, plus the inoculated person might die. So not only was it disgusting, it was also sort of terrifying.

Then one day it occurred to an English country doctor named Edward Jenner that milkmaids didn't get smallpox. Jenner hypothesized that their daily proximity to cattle protected them — cattle get a different kind of pox, called "cowpox," which is not lethal to human beings. So Jenner did what any respectable 18th-century doctor with a vague idea would do — he injected some cowpox into an 8-year-old kid, and then followed that up with an injection of smallpox. Lucky for that hapless little lab rat, the boy developed a typical case of cowpox and avoided smallpox altogether. Jenner's procedure was dubbed "vaccination," after the cowpox virus itself, Variolae vaccinae. Thanks to Jenner's innovation, smallpox and other lethal diseases have been all but eradicated from the world, and Jenny McCarthy has something to moan about. It's a win-win.

Scurvy

Pirates love shiny things, have eye patches, say "arrr" all the time, and have scurvy. These are the unwritten truths of piracy, as unshakable as rock salt and as unbreakable as that M. Night Shyamalan movie nobody saw.

For a long time, no one knew what scurvy was — just that it affected sailors and that it sucked. Also, there was a song about it on an episode of SpongeBob Squarepants, which was pretty awesome. People with scurvy bruised easily, and had swollen gums, loose teeth, and severe joint pain. Some estimatessay that over 300 years of maritime history, as many as two million sailors died from scurvy.

What was pretty obvious was that men would recover after disembarking, but because pre-18th-century people weren't very good at putting two and two together, it wasn't until 1747 that a British doctor named James Lind figured out that a diet of gruel, salted meat, and biscuits was probably not making anyone fab, fit, or fantastic. Lind reasoned that citrus fruit might give sufferers the nutrients they needed to combat the disease and a simple trial proved he was right — but he died before seafarers finally adopted his ideas, so scurvy continued to plague sailors for another 50 years. And even though there are no pirates sailing the seas today (at least not ones who say "arrr"), Slate says people do still get scurvy — blame it on a fruit- and vegetable-free diet of processed carbs, candy bars, and pizza.

Rabies

Smallpox, bubonic plague, ebola — history is full of terrifying diseases, but the most terrifying disease that you hardly ever think about is probably rabies. Rabies is said to be 100 percent fatal, which means if you develop symptoms of the disease, you're 100 percent dead. And that's a unique characteristic among viruses — even smallpox doesn't kill every person who gets it.

In 2004, a Milwaukee doctor named Rodney Willoughby developed a treatment protocol that appeared to save the life of 15-year-old Jeanna Giese. But the protocol had only limited success with other patients: Wired reported that of the 41 times it was tried between 2004 and 2012, only five patients survived. That's led some doctors to suggest abandoning the protocol altogether. (Isn't 12 percent survival at least 12 times better than 0 percent survival?)

Some doctors aren't even sure that the protocol has cured anyone — these naysayers think survivors might have been infected with a less virulent strain of the virus and would have lived anyway. That was apparently the case with the "Texas Wild Child," the first known case of abortive human rabies.

It's hard to know for sure, because the rabies vaccine prevents almost all would-be cases of the disease — sadly, that means there isn't a whole lot of interest in a true protocol for curing active rabies. So the real reasons why some people survive this "100 percent fatal" disease may never be fully understood.

1918 influenza

The 1918 influenza pandemic killed 50 million people in one year. Just to put that into perspective, that's roughly equal to the number of people who died during the Black Death, only the Black Death took seven years to run its course.

If you've ever talked yourself out of a flu shot based on the fact that you're young and healthy, here's another terrifying fact for you: The 1918 flu virus disproportionately killed people between the ages of 20 and 40, often sparing kids and the elderly. Until recently this has been a mystery — in a normal flu year, young adults don't have much to worry about. So what made the 1918 flu different?

In 2014, scientists at the University of Arizona looked at the origins of the 1918 flu virus, and theorized that it was just a typical H1 virus until a bird flu virus came along and said, "Hey, do you want some of this genetic material?" The H1 virus said, "Sure," and it then proceeded to wipe out 50 million people.

The bird flu genes made the virus especially deadly, but why did it target people in the prime of life? By looking at old blood samples, researchers learned that people born during the last two decades of the 19th century had antibodies for a completely different flu strain, while older people and children had antibodies for a virus that was similar to the 1918 virus — which would have helped them fight off the otherwise lethal bug.

Anesthesia

Modern medicine has given us lots to be grateful for, like vaccination, antibiotics, and thermometers that don't need to go up anyone's butt. But one of the greatest of all modern medical miracles is anesthesia — without it, routine surgery would be a living nightmare.

The miracle of anesthesia is also one of medicine's greatest mysteries. According to Massachusetts General Hospital, it was first demonstrated in 1846 by a Boston dentist named William T.G. Morton. In front of a crowd, Morton used ether to render a patient unconscious, and the crowd watched while a surgeon proceeded to remove a tumor from the patient's jaw. When the man awoke, he informed the crowd that he'd felt no pain — and so ended the era when surgery really, really sucked.

Despite everything it's done for us, scientists really don't know how or why anesthesia works. Theories abound — the most popular one is that the olive-oil-like consistency of the anesthetic stops neurons from firing, making it impossible for important parts of the brain to communicate with each other. But because we don't understand how consciousness works, we don't really understand unconsciousness either, which means we really don't understand what the heck is going on when we're under anesthesia. But hey, no one has to suffer during surgery anymore. Ultimately maybe the "why" just isn't that important.

Phineas Gage

The story of Phineas Gage is perhaps the most bizarre of all medical mysteries. According to Smithsonian, in 1848, 25-year-old railroad worker Phineas Gage was stuffing explosives into a hole when an explosion sent the metal rod he was using through his left cheek and out through the top of his head. You might think that was the end of Phineas Gage, except it wasn't — Gage not only survived but remained lucid enough to tell his physicians, "Here is business enough for you."

Gage's survival was miraculous but it did more for medical science than prove that it was possible to take an iron rod through the brain and live to talk about it. It was also the first case to link brain injury to altered personality. Gage was a changed man. He turned vulgar, insensitive, and flaky. His friends said he was "no longer Gage," which really isn't that strange when you consider that part of his brain was essentially cut off from other parts of his brain. Some people's personalities change when they're just cut off in traffic. Yet remarkably, Gage lived for more than 10 years after the accident, finally succumbing in 1860 to a series of seizures.