Who Was Bruce Ivins, The Man Behind The 2001 Anthrax Attacks?

The investigation into the 2001 anthrax attacks concluded when federal prosecutors named Army microbiologist Bruce Ivins the culprit. Investigators also announced that Ivins had acted alone. Since then, though, new information has emerged that casts doubt on that official version of events. Because of a tragic decision Ivins made before official charges were brought against him, in the minds of many, that uncertainty may never be fully put to rest.

In the 2001 anthrax attack, a number of letters laced with the dangerous bacteria were mailed through the U.S. Postal Service to notable individuals, including two Senate offices and several news outlets. Those contaminated letters killed five people and sickened many more in what was the worst bio-terrorist incident in U.S history, according to Slate. Though largely circumstantial, what led investigators to Ivins since that was part of his scientific area of expertise. He had access to the anthrax bacteria used on the letters because of his work at an Army lab. Additionally, there were other troubling aspects regarding his mental health, which were revealed during the FBI's inquiry (via the official website for the FBI).

Ivins offered to assist in the anthrax investigation

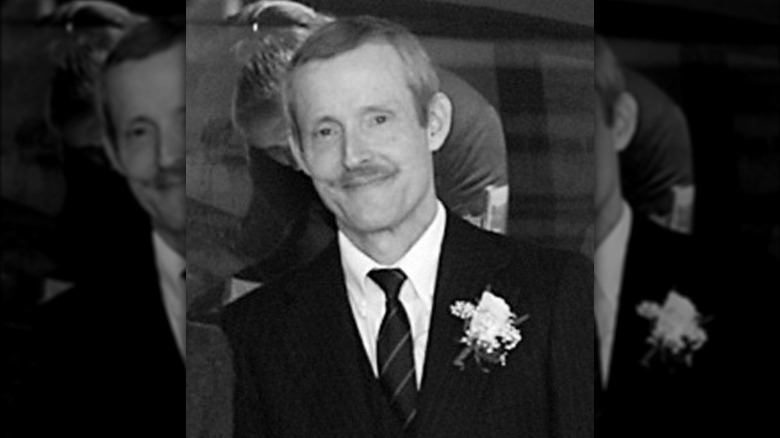

According to the Los Angeles Times (LA Times), Ivins (pictured) was born in 1946 and earned a doctorate from the University of North Carolina (UNC). As far back as the 1980s, Ivins was a leading expert on anthrax, a highly infectious and often fatal disease caused by a specific type of naturally-occurring bacteria called Bacillus anthracis, as the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) explains. Though a gifted scientist, Ivins also had private struggles including incidents involving guns and a stockpile of munitions such as bomb-making equipment that he kept in his basement. Ivins also had a personal vendetta against the Kappa Kappa Gamma sorority on the University of North Carolina (UNC) campus and elsewhere; many chapters of which he's known to have broken into. At the time, Ivins stole the sorority's cipher and ritual book (per the LA Times).

Nonetheless, Ivins managed to work his way into the biodefense industry and become a leading authority on the deadly anthrax bacteria. Among other breakthroughs, his work helped discover an improved anthrax vaccine. Ivins' most notable work was conducted at the germ research center at the U.S. Army Medical Research Institute of Infectious Diseases in Fort Detrick, Maryland, where he was granted a high level of security clearance. In the uncertainty that followed the 2001 anthrax attacks through the mail, the FBI turned to Ivins for advice and he readily offered his assistance, as ProPublica reports.

There were other suspects in the case

There were other suspects in the anthrax attack investigation, most notably Dr. Steven J. Hatfill (pictured), who had biodefense experience involving anthrax. In 2008, Hatfill was exonerated when a suit that he filed against the U.S. Department of Justice and the FBI for unfairly implicating him in the crime was settled, as The New York Times reports. Despite Ivins' purported willingness to assist in the anthrax investigation, attention from authorities was drawn to him because of a string of alleged safety standard violations at the lab he worked in which anthrax was studied. That included one serious incident in which Ivins reportedly found evidence of the dangerous bacteria on a colleague's desk. Ivins claimed that he took steps to clean it up, but he never reported the issue.

Ivins was also known to work long hours in the lab late into the night around the same time as the anthrax attacks. However, that alone was not uncommon. During the investigation, the FBI solicited help from the American Society for Microbiology, asserting that the guilty party was likely someone who had access to a lab, such as Ivins. It was then that a colleague of Ivins named Nancy Haigwood helped point authorities in his direction. Haigwood knew Ivins from his days at UNC, and since then, she continued to have a number of troubling experiences with him, according to The New York Times. When Haigwood learned Ivins was working with the FBI on the case, she thought to herself (via The New York Times), "He did it."

Mental health challenges continued for Ivins throughout his life

Among the evidence offered by Haigwood and others as to why Ivins should be considered a suspect were Ivins' continued unusual behaviors, including vandalism, stalking, and a grudge against the Kappa Kappa Gamma sorority, of which Haigwood belonged while in college, The New York Times reports. He also allegedly forged a letter in Haigwood's name while in college. Evidence later emerged that Ivins' obsessions with the Kappa Kappa Gamma could relate to Haigwood spurning his romantic advances. He even later admitted that he thought of killing her, as the Los Angeles Times reports. It was even determined that several of the anthrax-laced letters were mailed from Princeton, New Jersey, near a Kappa Kappa Gamma chapter house, according to Slate.

Haigwood aside, other signs of Ivins' mental health challenges were evident. This included a number of different emails in which he spoke openly of his mental health challenges, and in one case, he mentioned that his mother possibly had undiagnosed schizophrenia. His behavior caused great concern for mental health professionals who worked with him.

With Hatfill proving to be a dead end, the FBI reached back out to Haigwood in 2006 regarding Ivins. He was now a person of interest. Alarming personal behavior notwithstanding, what the person guilty of the anthrax attacks would need more than anything else was access to large amounts of anthrax spores, which is something that Ivins had.

If you or someone you know needs help with mental health, please contact the Crisis Text Line by texting HOME to 741741, call the National Alliance on Mental Illness helpline at 1-800-950-NAMI (6264), or visit the National Institute of Mental Health website.

Was Ivins guilty, after all?

Though it was officially concluded that Ivins was the sole person responsible for the 2001 anthrax attacks, skepticism remains as to whether or not Ivins was, in fact, guilty. In response to the government claim that the anthrax strain used in the attack came from Ivins' lab, a number of scientists and other individuals came and went from the facility and any one of them could have stolen samples, as Slate explains. According to skeptics of Ivins' guilt, it's far more likely that Iraq or Syria had more motivation to carry out an attack of this nature against the U.S. given the state of world affairs at that time. Those that assert this theory claim that authorities should have more closely examined that possibility instead of focusing on Ivins.

Additional evidence that Ivins may in fact be innocent of the crime includes inconsistencies that have emerged regarding how Ivins allegedly took steps to cover his tracks, per ProPublica. Despite reports of anonymously mailing letters, unusual and often troubling personal behaviors, signs of depression, and the fact that he alone had access to the strain of Anthrax spores, the preponderance of evidence against Ivins was circumstantial. For that reason, there's doubt in the minds of many close to the case that if it had gone to trial, he would have been convicted.

Ivins committed suicide in 2008

It may never be known for certain if Ivins did in fact carry out the anthrax attacks. Before official charges could be brought against him, Ivins died by suicide. At the time, Ivins was aware that authorities were closing in one him, and since the case never went to trial, we're left with only the official version of events, as the Los Angeles Times reports. Perhaps the most notable sign that Ivins could in fact be innocent was that no evidence of the anthrax spores used in the attack was found in any of Ivins' belongings, according to ProPublica. What's more, it's been proven unlikely that Ivins was motivated to commit the crime to collect royalties on his anthrax vaccine, of which he had a stake in the patent.

According to Claire Fraser-Liggett (pictured), director of the University of Maryland's Institute for Genome Sciences, speaking with Propublica, if the Ivins case had gone further, she'd be uncertain of the outcome. "Should he have had access to a potential bio-weapon, given everything that's come to light? I'd say no. Was he just totally off the wall, from everything I've seen and read? I'd say yes ... But that doesn't mean someone is a cold-blooded killer," Fraser-Liggett added. Others contend the evidence against Ivins amounts to more than enough to prove his guilt, even though it is circumstantial.

If you or anyone you know is having suicidal thoughts, please call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline by dialing 988 or by calling 1-800-273-TALK (8255).