What Mikhail Gorbachev's Soviet Union Was Really Like

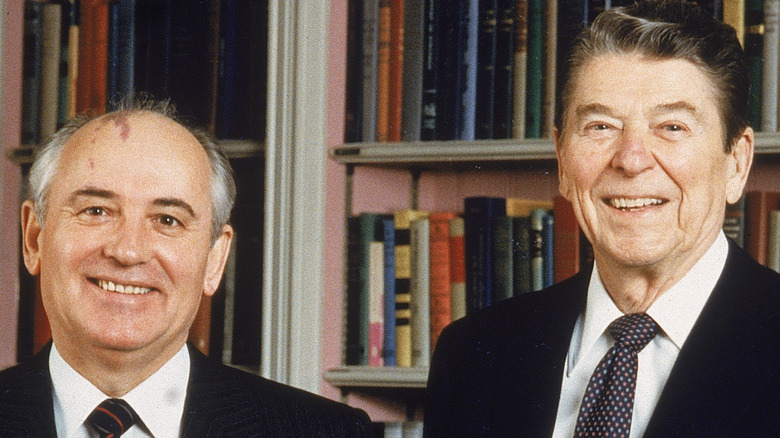

In the 20th century, the relationship between America and Russia was like a heavyweight boxing championship that never got to the ring, per The Washington Post. Plenty of mad talk came from both sides, but the nuclear solution proved too dismal to entertain. Perhaps that's why the conflict between these two geopolitical giants could be distilled down to the theme of 1985's "Rocky IV" and the fight between Rocky Balboa and Ivan Drago.

What many people forget is that the U.S. and Russia (the former Soviet Union) didn't always oppose one another (via the Ohio State University). Some scholars argue that Russia's neutrality (and continued trading with the 13 colonies) during the American Revolution helped the rebels secure victory. And this despite interventionist pleas by Great Britain. The U.S. also got a welcome boost from Russia's navy (on both coasts) during the Civil War, and the USSR's contribution to winning WWII shouldn't be underestimated despite an early alliance with Nazi Germany (via The Washington Post).

In the wake of Mikhail Gorbachev's death, Americans and Europeans celebrated his life, touting him as a world hero, per France 24. But Russia remained more ambiguous in its response. It appears that different perspectives continue to set these global powers at odds. (And that's not to mention Ukraine!) However, Russians remember what Gorbachev's Soviet Union was really like ... certainly, no rose garden. Here's what you need to know about life for Russians in the 1980s and 1990s as the Soviet Union disintegrated.

A sinking ship

Before Mikhail Gorbachev came on the scene, the Soviet Union had all the signs of a sinking ship, according to Britannica. Years of poor leadership and underrepresentation from regions outside of Russia left the economy in shambles and people disenfranchised, especially those who belonged to one of the many non-Russian ethnic groups living in the Soviet Union.

The upper echelons of the government and Communist Party could basically be summed up as old Russian males. But this didn't jive with the demographic makeup of the nation in the late 1980s, which Valerii Tishkov characterized as "one of the most multi-ethnic states in the world" in her article "Glasnost and the Nationalities Within the Soviet Union."

Besides a lack of representation for the country's many ethnic groups, other fractures also emerged in the old Soviet foundation. Mikhail Gorbachev, the leader of the Communist Party who became USSR leader, argued that his country's status quo didn't allow people to be successful or thrive. In Laurie Stoff's "The Rise and Fall of the Soviet Union," she describes the sinking Soviet ship as full of "internal contradictions." She also argues that Gorbachev's attempted reforms basically opened the hulls, letting the metaphorical water in more quickly. For the 286,717,000 (via Tishkov) still onboard, with no life vessels in sight, the future looked grim.

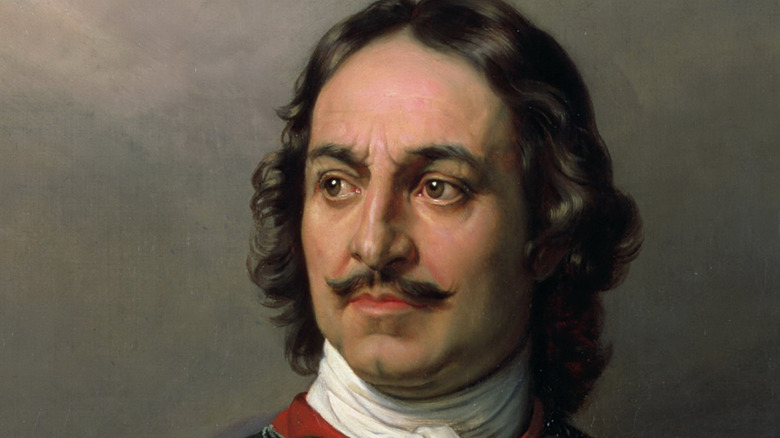

The inferiority complex that never went away

Russia, and by extension the Soviet Union, nursed a centuries-old inferiority complex in its dealings with the West. Ever since Peter the Great, Russians played catch up with Europe, as reported by The Nation. In fact, Tsar Peter went all-in on a forced "Westernization" program meant to bring the elite of Russia up to snuff with the culture of the Continent.

These social engineering attempts often came with unintended and downright disastrous results, however. After all, opening the floodgates to European influence in Russia also let in the works of German philosopher Karl Marx, the father of Communism. Marxism would eventually sweep the nation leading to the destruction of Imperial Russia, its royal family, and millions of people under Josef Stalin, per The Washington Post and Stanford.

When Gorbachev came into power headlining the Communist Party, he went right back to the same old playlist, trying to leap the gap between the USSR and the West, as reported by France 24. While his intentions were great, acknowledging the old inferiority complex did little to help the USSR navigate increasingly troubled waters. What's more, he underestimated what Westernization would ultimately do to the Soviet Union: "Gorbachev honestly believed he could reform the Soviet Union while maintaining the Communist Party's power — but he didn't understand ... that the Communist Party's power was the Soviet Union."

Rotten to the core

The captain and crew of this metaphorical "sinking ship" looked to various remedies, plugging holes to stay afloat. When Mikhail Gorbachev came to power as the General Secretary of the Communist Party in 1985, he also became the head plugger of these holes, as reported by History and Britannica. Gorbachev found himself between a rock and a hard spot.

After all, he was a dyed-in-the-wool Socialist who showed no signs of changing (via "The Rise and Fall of the Soviet Union"). But he also remained conscious of the West's successes and wanted to claim some of them for his nation, according to Investopedia. Gorbachev made the mistake of assuming some minor reforms could fix all the USSR's problems. But, boy, was he wrong!

"The Rise and Fall of the Soviet Union" points out that his reforms sent the economy into a tailspin while giving the Soviet people a bad faith vibe: "Although [Gorbachev's] intention had been to shore up and revitalize the ailing Soviet system, in effect his measures further discredited it in the eyes of the Soviet population." That said, trying to distill down what caused the fall of the Soviet Union is more complicated than that. In an essay published in December 2021 and entitled "Perestroika and New Thinking: A Retrospective," Gorbachev explored the ground game the USSR faced by the mid- to late 1980s. Admitting to his mistakes, he confessed a clear miscalculation when it came to reforms that inadvertently paved the way for collapse.

A thing called perestroika

In the mid-1980s and early 1990s, the Russian word "perestroika" hit the airwaves (via History), containing the promise of "restructuring," per History. Mikhail Gorbachev made this term a theme for one of two sets of reform policies he hoped would revamp the USSR starting in 1985. This approach wasn't something that he came to lightly.

In the Harvard Gazette, Gorbachev explained how he concluded that perestroika was a must. It was based on observations made while working at lower levels of government and with various Soviet leaders. It was also one that showed his intimate knowledge of how the system functioned and where the greatest flaws existed. But like many around him, he overestimated what a little reform could do, while underestimating the social costs (via History). That said, Gorbachev also had his fair share of critics.

"Perestroika and Glasnost Will Not Solve the Problems of the Soviet Union" explains these critics included "conservative Communist Party members [who] opposed these moves, believing they threatened the very fabric of Soviet society and would damage socialism, perhaps irreparably." These political controversies reflected a growing desperation as the broken Soviet economy made leaders look for solutions in unlikely places. Years later, Gorbachev reflected on being the last leader of the USSR, stating, "I have to admit that when we started perestroika, my colleagues and I did not see the full extent of that problem" (via Gorbachev's "Perestroika and New Thinking: A Retrospective").

And let's not forget about glasnost

The other term that defined Mikhail Gorbachev's reforms was glasnost, which translates as "openness," according to History. This had significant political repercussions for the people of Russia, ushering in what some characterized as the "democratization of the Soviet Union," per Britannica. Glasnost permitted new freedoms to the media and public criticism. But some say these liberties contributed to bringing down the regime and throwing its citizens into chaos and disarray.

Amid these changes, Nina Andreeva, a Soviet teacher living and working in Leningrad, wrote a letter explaining her concerns about the reforms and the repercussions she had already observed (as quoted in "The Rise and Fall of the Soviet Union"). Published in 1988, Andreeva argued that Gorbachev's reforms, including glasnost, led to a fragmenting of Soviet culture along many unprecedented lines.

Andreeva also claimed that it created problems that hadn't existed before "to one extent or another ... 'prompted' by Western radio voices or by those of our compatriots who are not firm in their notions about the essence of socialism." She likened the result to a sense of disorientation and destabilization right when the USSR most needed a strong and stable leader at the helm of the ship. Whether the Soviet Union could have been saved another way remains a contested topic (via Russia in Global Affairs). Nevertheless, Andreeva's letter presents a distillation of what many felt as they experienced Gorbachev's reforms firsthand and the sea change they brought.

Nostalgia makes for rose-colored glasses

A 2020 survey conducted by Levada Center asked the Russian people to reflect back on what life was like during the Soviet regime, according to Radio Free Europe. Surprisingly, many had nothing but positive things to say about the former Soviet Union. In fact, more than 60% characterized the benefits of living at this time as including "stability, order, and confidence in tomorrow." A similar percentage also expressed the conviction that the USSR never needed to fall.

For these individuals, Mikhail Gorbachev's reforms did more harm than good. According to France 24, these sentiments explain variations in perceptions about Gorbachev's legacy in the East and the West. While America and the European Union tend to see him as a type of savior that managed the balkanization of the Soviet Union without tipping off a nuclear war, many Russians have a different take on the matter.

According to Nick Holdsworth, France 24's Russia correspondent, "[Gorbachev] was a victim of the forces he set in motion and in this way, people blamed him for the collapse of the Soviet Union and the dreadful situation in Russia in the 1990s." But he wouldn't be the only victim. In many minds, Gorbachev took the whole nation with him.

From constant surveillance to social experimentation

For regular people living in the USSR in the 1980s, the societal and behavioral changes proved confounding, per "The Rise and Fall of the Soviet Union." On the one hand, they spent the first part of the 1980s under constant governmental surveillance (via The Atlantic). During this time, author Anya Schmemann would later reminisce, "Our phones were tapped, our apartment bugged, our mail opened, and we assumed that our government-provided housekeeper filed frequent reports on us."

Soviets spent the second half of the 1980s going Western, with a free press and elections. By 1991, the structure collapsed, and people faced unprecedented external influences and liberty verging on lawlessness, per Russia Beyond. Some call the post-Soviet decade the "wild 90s," similar in many ways to a runaway train.

Despite the challenges, optimism remained regarding the advantages of democratization and westernization, namely the introduction of Western brands. But scarcity and empty shop shelves came first. The lack of merchandise didn't even matter, however, because rubles tanked in value making extra purchases off-limits, according to Nick Holdsworth of France 24. He recalls the story of one girl whose parents set aside money to purchase her a vehicle. But by the time she could drive, rubles had nosedived so significantly that the savings had the buying power of a shirt, pants, or shoes. (Hopefully, they were comfortable walking shoes.)

Bread lines marked an aspect of daily life

Although the USSR had espoused the ideals of communism since the Russian Revolution of 1917, the practical application of Marxist principles proved disastrous, as reported by History. Between 1932 and 1933, millions of people died during the Great Famine. This period was brought on by the seizure of land and agricultural production from private citizens and placement of these resources into collective mismanaged and underproductive governmental holdings.

According to Russia Beyond, bread lines and ration cards became an early and haunting presence in the USSR. Without any form of accountability, the Soviet Union always suffered from a corruption problem as typified by despotic rulers like Vladimir Lenin and Josef Stalin. Although he doesn't get the same airtime as Adolf Hitler, Stalin did engineer a genocide on a par with Nazi Germany (via Stanford).

By the 1970s and the 1980s, the entrenched elites (aka the Politburo) enjoyed increasing wealth on the backs of the working class, according to History. All the while, the average Soviet barely scraped by, refining the art of creating serpentine breadlines. As Russia Beyond notes, the lines increased as the USSR ended. And it wasn't just bread that people waited in line to access with their government-rationed coupons. They also waited for oil, butter, sugar, alcohol, washing power, soap, and more.

A cartographer's nightmare

By the end of the 1980s, the Soviets woke up to regular news of regions withdrawing from the USSR, as reported by the Miller Center. How jarring for the average individual to watch the crumbling of their nation over a handful of years! Not only did these vast geopolitical changes represent a cartographer's worst nightmare, but they also contributed to the destabilization of the nation as regions noted for their natural resources made their exit.

The breakup began with regions like Estonia and Lithuania in 1988 and 1989, respectively. This meant saying bye-bye to Estonia's oil shale and Lithuania's timber (per the Republic of Estonia and World Atlas). Next came Latvia and Hungary and the loss of more natural resources. Ukraine was renowned for large deposits of methane, coal, and manganese, which the Communist superpower lost with its withdrawal in 1991 (via Britannica and PBS). According to Britannica, Poland offered the USSR much-needed coastal areas and harbors as well as natural resources like coal, which went with its membership in the USSR, finalized by the departure of the last Soviet soldiers in 1992.

The USSR had already been dealing with natural resource decline due to overuse and loss of renewables, according to the U.S. Department of Energy. This translated into increased prices for these resources right around the same time that hyperinflation and balkanization kicked in, creating a perfect, nation-breaking storm.

Leaving one epoch and heading into another

As the Soviets faced increasingly difficult times, the pressure was on when it came to the effectiveness of Mikhail Gorbachev's reforms, according to History. Yet, Gorbachev publicly stated, "The world is leaving one epoch and entering another. We are at the beginning of a long road to a lasting, peaceful era" (via the Miller Center).

As History points out, the way Gorbachev's reforms took effect could have been better planned out. Gorbachev's economic changes took time, and people suffered while finding their footing in new ways. But the openness side of things offered through glasnost happened very rapidly. This meant hardcore media criticism and scrutiny before the full effects of the economic makeover could be felt.

While some people savored this newfound journalistic freedom, it raised the ire of conservative Communist factions. One of these groups targeted Gorbachev's government in 1991 (via History), further exacerbating the many problems facing the Soviet Union.

Life in a communist-capitalist system

As Mikhail Gorbachev continued his reform experiments, Soviets found themselves living under a hybrid communist-capitalist system, per Foreign Policy. But as things went from bad to worse, it became clearer and clearer that the whole system required dismantling, which Gorbachev achieved one step at a time. To put it simply, "by the end of the 1980s, Gorbachev had concluded that ending the Communist Party's political monopoly was the only way to implement his economic agenda."

At the same time, however, the movement of the economy towards a free-market system contributed to new investments and brands in the former Soviet Union, as reported by the Associated Press. But these brands also faced a long road to getting established, and this road wasn't for the faint of heart. For example, Pizza Hut had trouble gaining a foothold and soon abandoned its first attempt.

But McDonald's enjoyed greater success by understanding that opening a fast-food restaurant in the former Soviet Union wasn't as simple as acquiring some real estate and putting up a sign. It required establishing a whole supply-chain network. This started with the importation of seeds and education for local farmers to help them increase crop yields. It also meant educating them about best practices in crop preservation and working on various cogs in the supply-chain infrastructure. It involved starting from the ground up.

Getting out of Russia became a must for some

As the USSR collapsed, many Russian women wanted out, as Russia Beyond details. They turned their attentions to finding foreign husbands, which made the appearance of marriage agencies commonplace. By the 1990s, approximately 90% of Russian women had placed their hope in marrying outside of their nation and relocating.

There were many reasons for this, some of them more cynical than others. The Moscow Times said, "Naturally, foreigners were viewed as a bridge to the most developed and 'civilized' West." That said, Russia Beyond and The Moscow Times disagree when it comes to how much Russian women prefer men from other countries today. While The Moscow Times interviewed a number of ex-pat males who feel their foreign status still helps them in the ladies department, Russia Beyond claims that just 7% of Russian women now actively look to leave the country on the arm of a foreign beau.

Whatever the case, there's not nearly as much hubbub about matchmaking and marrying non-Russian men now. What's more, as Russia Beyond points out, stories in Russian media outlets have long focused on horror stories from women who relocated and allegedly got treated poorly (or even killed) by their so-called rescuer-spouses. To quote Bob Dylan, "The times, they are a-changin'."