The Violent 1835 Execution Of Saint Joseph Marchand

Even through his searing pain, Father Joseph Marchand stood firm in his Catholic faith. In 1835, the emperor of Vietnam, Minh Mạng (also sometimes written as Minh Mệnh), had ordered the 32-year-old priest and missionary to die by a brutal and painfully slow form of execution, according to The Month: A Catholic Magazine and Review. This type of state-sanctioned killing had been in use in parts of Asia since the 900s, according to Google Arts & Culture.

Father Joseph Marchand's excruciatingly painful death that he suffered for his faith, considered martyrdom by the Catholic Church, would eventually earn him sainthood. But it would take more than 150 years for that to happen as part of a huge Vatican ceremony overseen by Pope John Paul II in 1988 for Marchand and 116 others collectively known as the Martyrs of Vietnam, according to the Associated Press. Some of Marchand's fellow Catholics were given swifter, and therefore more merciful, deaths through beheading, while others were starved to death as they sat in public cages, per the Vatican News.

Who was Father Joseph Marchand?

Father Joseph Marchand was born in Passavant, France on August 17, 1803, to a peasant family and received no formal education until his teens, according to The Month: A Catholic Magazine and Review. The naturally gifted Marchand was admitted into the seminary in 1821, and at age 25 Marchand joined the Paris Foreign Missions Society, per CatholicSaints.Info. The Society began in the 1650s to convert non-Christians to Catholicism in North America and Asia, according to Versailles Century.

Father Joseph Marchand sailed for Vietnam in the spring of 1828 and when he arrived began proselytizing in Saigon (now Ho Chi Minh City) and traveling as far as Phnom Penh, in Cambodia, according to the "Historical Dictionary of Ho Chi Minh City." In 1832, Marchand was offered the position of head of the Paris Foreign Mission Seminary in his home country, but turned the job down to continue his work in Vietnam, per CatholicSaints.Info. This decision would seal his fate.

A Vietnamese emperor with anti-Christian sentiments

Emperor Minh Mạng was a faithful Confucian and believed the influx of Catholic missionaries to Vietnam represented a direct assault on his nation's belief system, per Britannica. The emperor's hold on his crown was shaky — his mother was the former emperor's concubine — and the Christian religion contradicted the emperor's standing as a divine emissary, per Britannica. The emperor was intelligent, well-read, and inquisitive, and had read parts of the Bible but his Confucianist beliefs clashed with the stories he read in the Bible, per "Southern Vietnam Under the Reign of Minh Mạng (1820-1841)."

The emperor attempted to stave off the encroaching new religion by ordering all the Catholic missionaries to Huế under the guise of needing interpreters, and banned any new Catholic missionaries from entering the country, per Britannica. Finally, Emperor Minh Mạng sent the Catholic missionaries packing back to France, but many of them snuck back into the country, according to Britannica.

A rebellion makes things worse for Catholics

A rebellion made matters worse for the Catholic missionaries in Vietnam. Amid the emperor's anti-Christian campaign, a rebellion broke out in the southern part of the country in 1833. There are competing accounts of Marchand's role in the uprising — that he was intimately involved, merely a victim of circumstance, or a naïve political pawn, according to "Extortion and Exploitation in the Nguyễn Campaign against Catholicism in 1830s-1840s Vietnam."

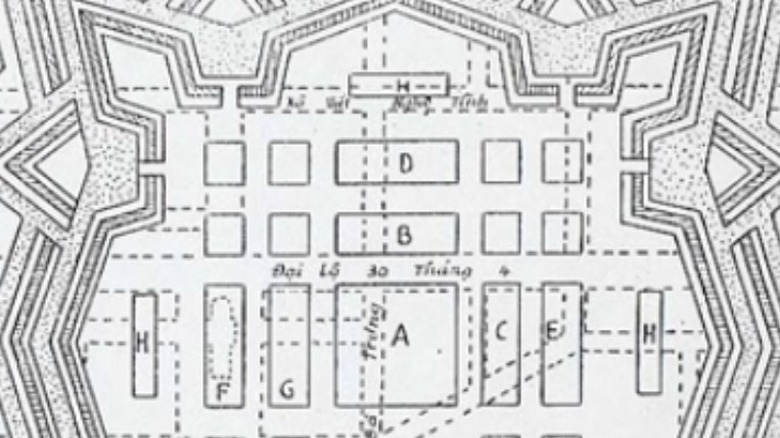

The emperor believed Marchand and many other French Catholic missionaries had sided with the rebels who wanted to replace Emperor Minh Mạng with My Duong, who was a Catholic and a grandson of the former emperor. The rebels took the Saigon Citadel, an 18th century fortress (pictured above), which they held for two years before being defeated by the Emperor's army in 1835, per the "Historical Dictionary of Ho Chi Minh City." Among the prisoners sent to Huế to face trial was Father Joseph Marchand, whom Minh Mạng considered the leader of the Christians involved in the rebellion, per "Extortion and Exploitation in the Nguyễn Campaign against Catholicism in 1830s-1840s Vietnam."

This brutal execution method originated in China

At his trial, Father Joseph Marchand denied being involved in the rebellion and refused to renounce his faith or step on a cross, according to the 1864 book "Christian Missions: Their Agents and their Results." The authorities then began their brutal form of execution. They used tongs heated until they were red hot to strip off the flesh and muscles of the victim. Over two days, they tortured Marchand and while he screamed in pain, he remained steadfast in his faith, crying out "Oh my Father!" before eventually succumbing to the torture, per "Christian Missions."

Marchand's execution was a variation on a form of killing known as Lingchi and translated as "death by a thousand cuts," according to Google Arts & Culture. It originated in China in about 900 and found its way to Vietnam and Korea during Chinese conquests in the ensuing centuries. Its last known use was in China in 1905, according to Google Arts & Culture. During this period of Vietnamese history, the emperor persecuted many Catholics, both European and Vietnamese, per "Southern Vietnam Under the Reign of Minh Mạng (1820-1841)."

Father Joseph Marchand becomes Saint Joseph Marchand

The Catholic Church declared Father Joseph Marchand "venerable" only five years after his martyrdom, per The Month: A Catholic Magazine and Review. This is the first step in the process of sainthood, according to the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops (USCCB). Then in 1900, he was beatified, per the "Historical Dictionary of Ho Chi Minh City." Beatification, the next step in the process, involves an investigation into the potential saint's past to determine whether they're truly worthy of sainthood, with martyrdom being one way in which a person can achieve this goal, per the USCCB.

On June 19, 1988, in a ceremony at the Vatican that drew thousands of Vietnamese refugees who had fled their country in the wake of the Communist takeover, Pope John Paul II canonized Father Joseph Marchand, elevating him to sainthood, per the Associated Press. Marchand was one of 117 martyrs of Vietnam from the 18th and 19th centuries who were canonized that day, per the AP.