The Time Vermont Was An Independent Country

The small New England state of Vermont today is known for its beautiful mountains, lakes, skiing, and hippies. It is also considered politically insignificant, with a mere three electoral votes that are unlikely to have any impact on future national elections. But this small state once punched well above its own weight, not as part of the United States, but as an independent republic.

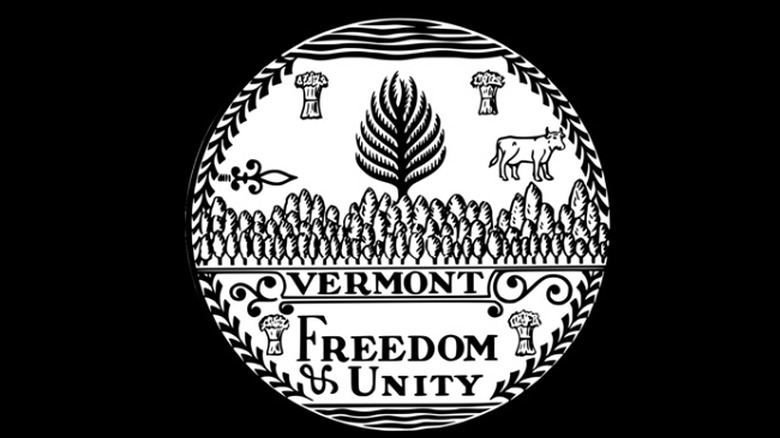

The Republic of Vermont, as it was called, was a trailblazer of sorts. Per the Journal of the American Revolution, in its short, 14-year existence, the republic guaranteed universal male suffrage, abolished slavery, and established public funding for education — all of this enshrined in the national constitution, which predated its American counterpart by a decade.

The country would eventually opt for membership within the United States, and its legacy has been largely forgotten. Here is the story of how the Green Mountain State held its head high in the original rebellion against the United States.

The settlement of Vermont

Although located in the New England region, Vermont was not one of the original 13 Colonies that formed the United States. In fact, in the early colonial era, the area was a bit of a borderland. According to the National Park Service, Vermont's first European settlers were French soldiers and traders, who established a series of outposts linking French Canada to the British colonies of New England.

As the French were moving south from Canada, the New England colonies were growing and expanding northward at a time when Anglo-French tensions both in Europe and North America were simmering. As a result, in 1754, the French and Indian War broke out, spreading into Vermont, per the Vermont Historical Society. The native Abenaki allied with the French, who had cultivated friendly relations with them through trade and missionary activity, against the British, who instead courted the Abenaki's traditional enemies – the Iroquois of New York.

With the 1763 Treaty of Paris, the British gained control of Vermont and expelled the Abenaki and their French allies, many of whom sought refuge in the former French domains of Canada. Vermont was now fully open to settlement from New England. But trouble had already been brewing since before the war, as New York and New Hampshire fought over who would control the territory – especially once it passed firmly into British hands.

The NY-NH land grants dispute

At the center of the problems was the colony of New Hampshire, which embroiled itself in a series of disputes with its neighbors Massachusetts and New York. According to the Journal of the Vermont Historical Society, the dispute with Massachusetts was settled in 1740 through royal decree. The arbitration handed New Hampshire more territory than expected, including a small Atlantic coastline.

With the success of the Massachusetts arbitration, newly-appointed New Hampshire governor Benning Wentworth turned his attention to a much more difficult boundary dispute with New York. Now, problems with the future Empire State were nothing new. The colony had already clashed with Connecticut and Massachusetts over land, and now claimed all land up to the west bank of the Connecticut River (the current boundary between New Hampshire and Vermont) as its own.

Since the crown had not ruled on the boundary and New York did not hold any actual sway in the disputed areas, Wentworth went ahead and started making large land grants to prospective colonists and speculators for land west of the Connecticut River, hoping that if the British Crown did adjudicate, it would assign those areas to New Hampshire out of practicality. The dispute was briefly shelved during the French and Indian war. But as the Vermont Historical Society notes, many of the war's veterans applied for grants following its end in 1763. But they were applying from New York, and soon land disputes arose from different grants of the same land, forcing the colonies to appeal to George III to settle the boundary.

New York wins

According to the Journal of the Vermont Historical Society, New York's representatives lobbied George III for years before the final settlement in 1764. The colony argued that the land in question was crucial to its economy, particularly with Albany as an important trade hub. New Hampshire argued that it would not be able to support an independent colonial administration in such a small territorial space, making the disputed region necessary (it argued) to its continued existence.

The British king ruled in New York's favor, accusing New Hampshire governor Benning Wentworth of making the land grants for personal profit rather than public interest and voiding them all. New York's new boundary became the Connecticut River (swallowing up parts of Massachusetts and Connecticut, too). But there was one caveat. According to the Burlington Free Press, any settlers who had already planted roots in the area thanks to a New Hampshire land grant would be allowed to retain their lands.

Despite royal promises, New York did not honor the king's decision. Instead, New York invalidated all the land grants and told the New Hampshire settlers that they had to re-purchase their lands from New York – even if they had already been living there since the 1740s when Wentworth made the initial grants. But some of the rough-and-tumble frontiersmen saw it another way, and so entered one of the United States' most famous militias of the American Revolution.

Enter the Green Mountain Boys

American students likely have heard of the Green Mountain Boys and their leader Ethan Allen in the context of the American Revolution. According to the American Battlefield Trust, this militia is famous for its capture of Fort Ticonderoga from the British in 1775 – the first American offensive victory of the war. But the Green Mountain Boys originally got their start not against British Redcoats but against encroaching New Yorkers.

According to the Journal of the American Revolution, Allen formed the Green Mountain Boys to protect the ~61,000 acres of land citizens of New Hampshire had settled between the Connecticut River and Lake Champlain against New York's authorities attempting to run them out. The Green Mountain Boys thus attacked New York's forces attempting to enforce the colony's claims on Vermont, and, although the skirmishes were often non-lethal, significant property damage occurred. But the militia achieved its goal. With Allen and his paramilitaries running around, New York could not resolve any of the land grant disputes in favor of its citizens. Allen and his men caused so much trouble that New York even offered cash bounties for their capture.

Once the American Revolution broke out, Vermont became an important battleground between American forces and British troops from Canada. Vermont would fight with the United States, contributing soldiers to the crucial Saratoga Campaign.

The Battle of Bennington

As noted earlier, the Vermonters under Ethan Allen threw their lot in with the American Revolution and soon faced a British invasion in 1777 under General John Burgoyne. According to the American Battlefield Trust, Burgoyne sought to cut off New England, the heart of the American Revolution, from the Southern colonies, where many Loyalists lived.

Part of Burgoyne's army marched on the town of Bennington looking for supplies. This force of ~1,000 German soldiers and loyalists confronted an American force under General John Stark. In the ensuing battle, the British detachment was destroyed and Burgoyne's army was forced to continue south with 1,000 fewer soldiers. His force eventually met its end at the famous Battle of Saratoga, commonly viewed as the turning point of the Revolution.

Although General Stark is generally given credit for the battle, the American Antiquarian argues that there was much more than meets the eye. The journal notes that a regiment of Vermonters raised by Ethan Allen's brother Ira fought alongside the American forces. In fact, it was the Vermonters who convinced Stark to fight the British at Bennington in the first place. But although the Vermonters aided the Americans against the British, it does not seem they were fully committed to the United States. At least, this seems like the only possible interpretation because Allen and other prominent Vermonters had already decided by 1776 to form their own republic if the Continental Congress did not grant them a place in the new nation.

A new republic

Before the Continental Congress issued the Declaration of Independence in 1776, there was the question of whether there would be 13 or 14 colonies in the fight. According to the American Antiquarian, Vermont's prominent citizens decided to petition Philadelphia to recognize it as the 14th state of the new nation known as the United States of America. Ethan Allen's brother Heman delivered the petition, which the Congress rebuffed in the face of fierce opposition from New York. Instead, the Congress recommended that Vermont submit to New York and join in the fight against a common enemy. In return, New York was to respect Vermonters' property rights.

After several more months of failed politicking, Ira Allen and a handful of other notables took matters into their own hands. On January 15, 1777, Allen issued the Declaration of Independence of the Republic of New Connecticut. Now, the document was not a declaration of independence from Britain. It was a declaration of independence from the United States addressed to the Continental Congress. The document cited the republic's grievances against New York. New Connecticut accused New York of trampling over Vermonters' property rights while denying the area representation in New York's assembly. The decision to void land grants, against which Vermonters had no legal recourse, gave Vermonters no choice but to assert their right as free and sovereign people to establish a government to protect the property and rights of its citizens against unwarranted overreach.

For the Founding Fathers in Philadelphia, such a sentiment would have been familiar – it was the exact same reasoning that justified the American Revolution.

The Vermont Constitution

Among the first actions of the new republic was to write a constitution enumerating and guaranteeing the rights of its citizens. According to the Journal of the American Revolution, Vermont's founders drew upon the ideals of the European Enlightenment and the Pennsylvania constitution, known for its egalitarianism relative to the other colonies. Thus, the general point of the document is familiar: governments are instituted by the people for the protection of their inalienable rights, among which is the right to "reform, alter, or abolish government" in a manner "conducive to the public weal."

While the overall direction of the Vermont Constitution is similar to its U.S. counterpart, there are some differences regarding religion, suffrage, and slavery. The Vermont Constitution granted broad religious liberty, but only protected Protestants from deprivation of rights on religious grounds. It also enshrined observance of the Sabbath (Sunday). Regarding suffrage, all freemen had the right to vote and hold public office, unlike the United States, which maintained property qualifications into the 19th century.

The most interesting difference regards slavery. Chapter I, Sec. I, the beginning of the document after the preamble. Much like the U.S. Declaration of Independence and Preamble of the Constitution, Vermont declared that all men were born free with certain inalienable rights, including life, liberty, property, and the pursuit of happiness. Thus, it followed that no adult male over the age of 21 (or female over 18) could be held in any sort of bondage. This was effectively an abolition of adult slavery, at the time a radical idea, although it encouraged indentured servitude of poor children.

The Haldimand Affair

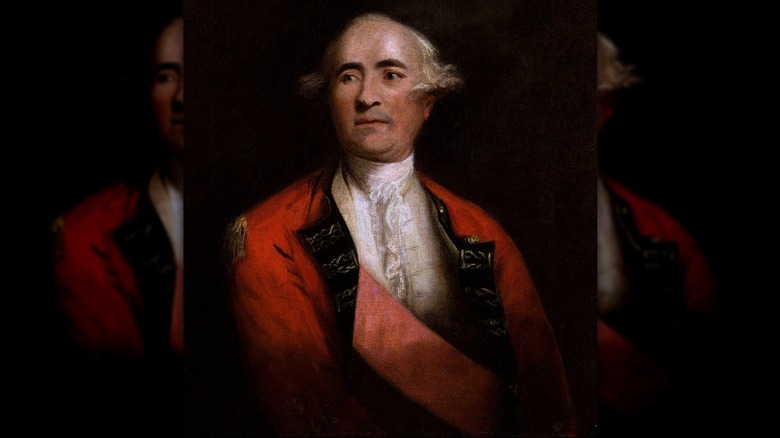

As noted in the Journal of the American Revolution, the war was stalemated by 1780. In a bid to win, the British decided to fight George Washington indirectly. First, it bribed a handful of American generals – including Benedict Arnold – to desert the cause. Second, it sent a 6,000-strong army under Charles Cornwallis to rally loyalist elements in the southern states.

Meanwhile, Vermont had been left at Britain's mercy. The republic's forces were mostly in New York, and the British were in control of Lake Champlain. Furthermore, the United States refused to recognize Vermont as a state. So, Ethan Allen decided to negotiate a separate peace with Britain. The terms ideally were that Vermont would return as a constituent republic within the British Empire. In return, the crown would recognize Vermont's claims against New York.

According to the Bennington Museum, Allen spent 1780-81 negotiating with the British governor-general of Quebec Frederick Haldimand. The British general proclaimed that the crown would protect Vermont if the United States attempted to invade. Vermont would also enjoy free trade with Quebec and Britain. In return, Allen promised not to "Confederate with Congress."

Ultimately, the plan failed. George Washington's defeat of Cornwallis' army with French aid at Yorktown in 1781 and the subsequent Treaty of Paris in 1783 led to British recognition of the United States. Haldimand suspended all British military guarantees to Vermont, although the republic continued to court British favor. But as time went on, it became clear that Vermont's destiny lay with the United States. It was just a matter of time.

Eight years of prosperity

The American Revolution ended in 1783. But although calm and economic prosperity came to Vermont, the republic was technically still in a state of rebellion against New York and the United States. So, how did Vermont manage to remain independent, and why did it choose this path? In part because, as the American Antiquarian notes, Vermont had no reason to join the Union.

Since Vermont was not de facto subject to the United States, it exited the American Revolution with one major advantage – it was debt-free. Its taxes were also low to nonexistent. All this, combined with the availability of land, led to a flood of settlers, which bolstered the republic's population. The country, per the University of Notre Dame, even had its own mint issuing coins called "Vermont Coppers." Vermont, despite its small size and statute, had all the hallmarks of a fully-functioning, independent state.

But despite its proud independence, Vermont's inhabitants never forgot their ties to the United States. As several Vermont Copper designs show, one of the country's nicknames was "the fourteenth star," which referred to the petition to join the United States as the 14th colony back in 1776.

Shays' Rebellion

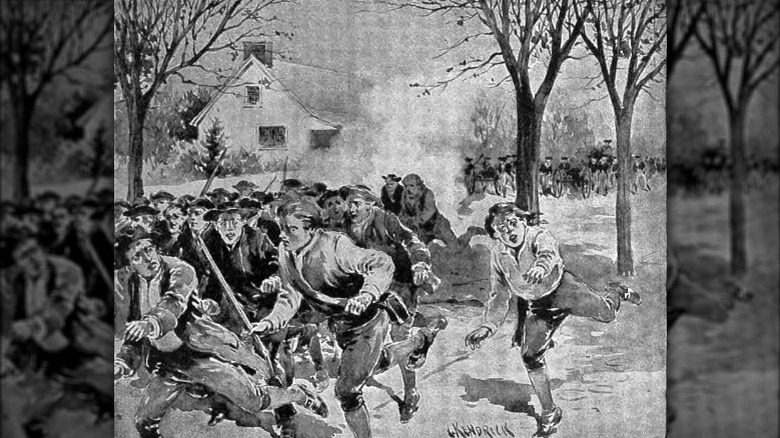

According to the book "The Tribes and the States," the 1786 conflict known as Shays' Rebellion laid bare the vulnerabilities of the newly-formed United States. Amid conflicts over taxation and debt payments, farmers under Revolutionary War veteran Daniel Shays rebelled in Massachusetts. Although the uprising was eventually defeated, the Republic of Vermont proved a stumbling block to suppressing it definitively.

After the rebellion's suppression, many insurgents fled to neighboring states. Now, New Hampshire, New York, and Connecticut all handed the rebels over to Massachusetts for punishment refuge. But some had also escaped to Vermont, which as a de facto independent republic, was out of reach of the Massachusetts and American justice systems.

Massachusetts offered Vermont a deal: If Vermont would hand over all rebels in its territory, Massachusetts would drop all claims to Vermont's territory. Vermont rejected the deal, saying that extradition would discourage immigration to Vermont, which the republic needed to drive its economic growth and expansion.

The Fourteenth State

By 1790, Vermont had become a bit of a thorn in the U.S. government's side. According to the Vermont Historical Society, not only had the country sheltered fighters from Shays' Rebellion, but it had also attempted to annex parts of New Hampshire from the United States.

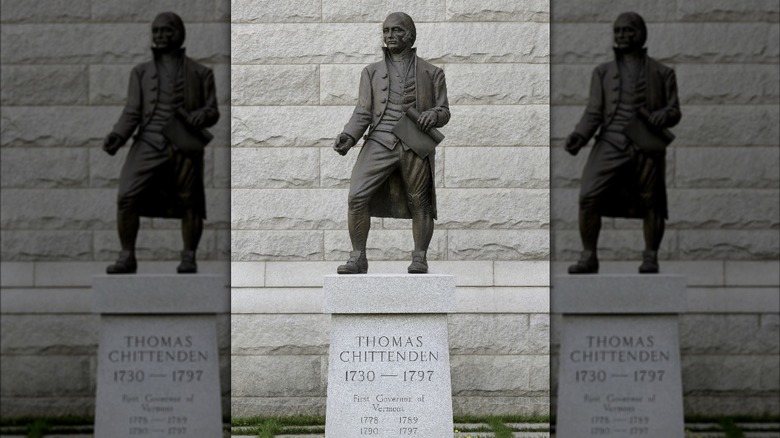

Despite the problems, there was hope for a solution. According to the New England Historical Society, Ethan Allen, the main agitator for Vermont independence, and his brother Ira had become unpopular due to their roles in the Haldiman Affair that nearly saw them hand Vermont over to British rule. But by 1789, Ethan was dead while Ira was off trying to seize Canada with French assistance. Without these two firebrands, Vermont's leaders, particularly Thomas Chittenden, had more flexibility.

In a series of compromises, Chittenden negotiated Vermont's independence from its neighbors. New Hampshire agreed to recognize the area west of the Connecticut River as Vermont in return for Vermont dropping all claims to New Hampshire's territory west of the Massachusetts state line. On October 28, 1790, the republic settled its long-running conflict with New York. In return for $30,000, New York dropped all claims to territory east of Lake Champlain and, crucially, its opposition to Vermont's statehood. With the final barrier to admission removed, Vermont ratified the U.S. Constitution in 1791. This short-lived republic had finally achieved its dream of becoming the 14th State. Vermont's statehood marked the end of the American Revolution, as the last remaining party to the conflict joined the Union on its own terms as a proud and unconquered republic.