The Scary Time Wayne Newton Was On A Reputed Mobster's Hit List

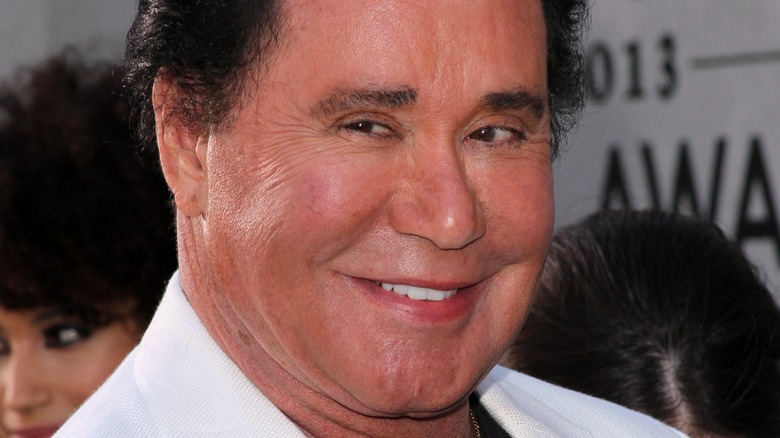

It's no secret that the Mafia and Las Vegas have a long, notorious history together. Singer Wayne Newton (shown above), whose famous crooning stage show remains a blueprint for the performances that are a crucial part of Las Vegas entertainment, was once targeted by the Mafia thanks to his relationship with a reported mobster. It's a story full of complicated twists and turns that played out in a real-life courtroom drama.

According to People, the trouble started for Newton, also known as The King of Las Vegas, in 1980. The famous Aladdin Hotel, one of the many kitschy hotels found on the Las Vegas Strip, had fallen on hard times and the owners made a deal to sell Newton and his business partner, Ed Torres, the hotel for $85 million. In September 1980, as reported by the Associated Press, Newton attended a gaming licensing hearing, after which he was approached by NBC reporter Brian Ross. Ross had some questions for Newton about his relationship with a man named Guido Penosi. At first, Newton stated he and Penosi originally met while Newton was performing at the Copacabana nightclub in New York City in 1973. Newton claimed that while the two had talked a few times in the following years, he only thought of Penosi as a fan.

How well did Wayne Newton know Guido Penosi?

The relationship between Wayne Newton and Guido Penosi (shown above) seemed a little more complicated than performer and fan. According to the NBC report by Brian Ross, which ran on October 6, 1980, just before Newton announced he was buying the Aladdin, Newton contacted Penosi for help with "a problem." Penosi reportedly got Frank Piccolo involved. Piccolo was a known associate of New York's notorious Gambino crime family. According to federal investigators, Piccolo started telling people that he had taken care of Newton's problem and was now a silent partner in the Aladdin deal (per NBC). At the gaming licensing hearing, Newton denied having any silent partners, referred to Penosi as a fan and family friend, and said under oath that he was unaware of Penosi's association with the Gambino family. Newton rebuffed Ross when he attempted to ask questions in a parking lot after the hearing. Ross reported that Newton was likely to be asked before a grand jury to testify against Penosi as part of a federal investigation.

Per the Associated Press, Newton later described the interaction with Ross as "... accostive, he was on the verge of badgering me ... I was bewildered. It was Gestapo tactics at work. I was angry because of the way I was being attacked in the hall." He also eventually admitted that the problem he'd brought to Penosi concerned death threats against his young daughter, which stopped after he asked Penosi for help.

Did NBC defame Wayne Newton?

Wayne Newton filed a defamation suit in April 1981 against NBC, Brian Ross, and producer Ira Silverman. During the trial, as reported by the Associated Press, Newton testified that he'd told his wife "I'm a dead man" upon seeing the news report and was soon contacted by the Las Vegas police who told him a contract had indeed been taken out against him. Newton began wearing a bulletproof vest, staying at the Aladdin instead of his home, and leaving his suite only to perform his nightly show, noting, "When you're told you're on a hit list for the Mafia it doesn't exactly make your day." NBC, Ross, and Silverman stood by their story, testifying that they had never said Newton was involved in organized crime and that Newton had lied about his relationship with Guido Penosi.

On December 18, 1986, The New York Times reported that after an eight-week trial, a jury had decided that Newton had been defamed by NBC, and awarded him $19.2 million in damages. According to another New York Times article, a federal judge later reduced the amount awarded to Newton to $5.2 million. NBC appealed the decision, and on August 31, 1990, a federal appeals court overturned the 1986 decision, writing that there was ”almost no evidence of actual malice, much less clear and convincing proof," on the part of NBC and its employees.