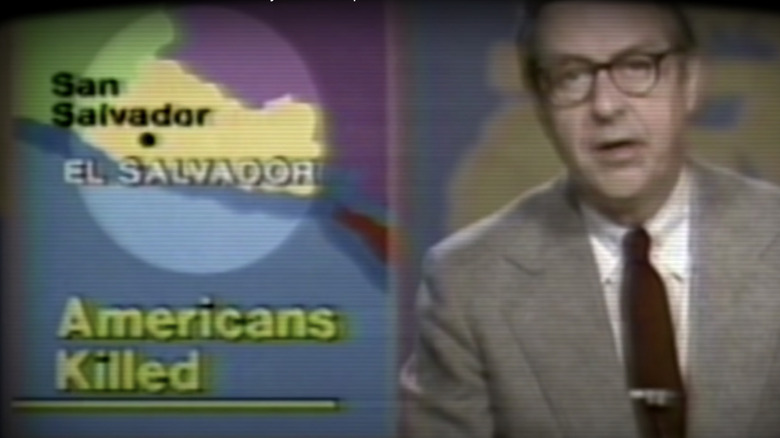

The Truth Behind El Salvador's Disturbing Church Murders

On December 2, 1980, Sister Dorothy Kazel and Jean Donovan, a Catholic missionary, drove to the airport in San Salvador, El Salvador. They picked up fellow Sisters Maura Clarke and Ita Ford (per Origins). Later that night, all four women were murdered. Their killings set off a scandal and cover-up that reached the Oval Office and the halls of the United Nations.

The night before their murder, Kazel and Donovan visited the house of U.S. Ambassador to El Salvador Robert White. Over dinner, White and the missionaries discussed El Salvador's right-wing military and the increasing violence against the peasant and working classes, writes The Atlantic. Death squads ran rampant, and massacres were common. Kazel and Donovan expressed their commitment to staying in El Salvador to help the poor and oppressed. According to Origins, their philosophy aligned with the then recently assassinated St. Oscar Romero, who promoted addressing "the cause of the poor as well as their needs." The church's alliance with the poor meant resisting the military government and supporting the victims of state-sponsored violence. But the church's defiance meant danger.

Due to nightly curfews, Kazel and Donovan stayed overnight at Ambassador White's house. The next day, the women enjoyed breakfast with the ambassador's wife and departed for the airport. Three days later, Ambassador White watched authorities unearth their bodies from a shallow grave.

The military government feared the church

In the last few hours of their lives, Sister Dorothy Kazel and Jean Donovan picked up Sisters Maura Clarke and Ita Ford from the airport. Ford and Clarke were returning from Nicaragua, where they attended a regional conference for missionaries. A roadblock set up by military men in plain clothes met the women outside the airport (via The Atlantic). These men would be their executioners.

Initially, the women set out to El Salvador to spread the Catholic faith. However, they adopted a new philosophy while working within the Chalatenango and La Libertad communities. Liberation Theology emerged within Latin America during the 1960s and aligned social change with Catholic morals. Liberation theologists consider all forms of oppression and exploitation as sinful, explains Origins. However, supporting the poor made the church a communist threat in the eyes of the right-wing military government. A military saying emerged: "Haz patria, mata un cura," which translates to "Be a patriot, kill a priest."

The women were clear-eyed about the dangers they faced. One month before the murder, Ita Ford recounted an interaction with the military. "The colonel of the local regiment [Ricardo Augusto Peña Arbaiza] said to me the other day that the church is indirectly subversive because it is on the side of the weak ... It's very contradictory to their National Security ideology," she said, per Origins. The military's distrust of the church would soon seal her fate.

The women's bodies are discovered

The day after the women disappeared, searchers found their burned-out van 5 miles from the airport. The women were still missing. U.S. authorities received a tip about the location of a death squad dumping ground, reports Origins. Ambassador Robert White and his team inquired about the missing women until they heard a grim report. He remembers (per The Takeaway), "I found the town clerk, and he told me that they had heard the screams and the shots the night before, and that it was the military that had done it."

The next day, a search team discovered the bodies of Dorothy Kazel, Jean Donovan, Maura Clarke, and Ita Ford. As the tip predicted, the killers hid the women at the rumored dumping ground, piling their bodies on top of each other in a shallow grave, writes The Atlantic. The killers raped the women and shot them execution-style. The reaction from those on the scene was one of horror. Carl Gettinger, the U.S. Embassy worker who eventually helped locate the killers, said of the crime (via The Atlantic), "Roman torturers of the early Church martyrs could hardly have come up with a crueler or more humiliating end for these four disciples of Christ." The murders were a turning point for Ambassador White. He remembers (per The Takeaway), "You realized at that point that the Salvadoran military was out of control — they would kill anybody." Both governments reacted with deception and denial.

Reactions to the murders are surprising

The responses to the murders were intense but vastly different. Ray Bonner, a former correspondent for The New York Times, tells The Takeaway, "It's hard to overdramatize how important this was and how shocking it was." He explains, "There had been 10,000 murders in El Salvador that year ... But nothing caused a reaction like the killing of these American churchwomen."

Reactions from Catholics around the world were twofold. Liberal Catholics, who believed in the tenets of Liberation Theology, were galvanized to support the oppressed people of El Salvador and those on the ground helping them, says Origins. Conservative Catholics thought the killings were somewhat justified or at least inevitable since they considered the missionaries to be communists, which — in their eyes — made the women criminals.

The U.S. took a similar stance. Bonner explained to The Takeaway that, at the time, the U.S. considered El Salvador "the frontline in the war against Soviet expansion and Soviet communism." The U.S. had a long-running policy of supporting authoritarian governments as long as they were pro-U.S. Because of that, the U.S. had been funding El Salvador's right-wing military government, supplying them with money, weapons, and training, according to The Atlantic. In an interview with CNS (via Global Sisters Report), Chalatenango's Bishop Oswaldo Escobar Aguilar points out the tragic irony. He explains that the women "were victims, we could even say, of the weapons of their own country."

The U.S. continued to fund El Salvador's military

Responding to the murders, Jimmy Carter's administration withdrew financial support from El Salvador. Soon, the Regan Administration reversed the decision, calling it a mistake, says Origins. Money and resources once again flowed to El Salvador's military. To justify this, Jeane Kirkpatrick, U.S. Ambassador to the United Nations, claimed (per Origins), "The nuns were not just nuns ... They were political activists on behalf of the Frente [the Salvadoran guerrillas]." Elsewhere, Secretary of State Alexander Haig spread false alternatives (per The Takeaway): "Perhaps the vehicle that the nuns were riding in may have tried to run a roadblock." But Bonner told the outlet that Haig defied the facts: "Ambassador White had been at the scene. He knew what happened; he talked to people. But Central America was at the center of U.S.foreign policy at the time."

Of the U.S.'s support for El Salvador's military, Regan said (via The Takeaway), "El Salvador is nearer to Texas than Texas is to Massachusetts ... Central America is simply too close and the strategic stakes are too high for us to ignore the danger of governments seizing power there with ideological and military ties to the Soviet Union." The U.S. had grown nervous about the region after Nicaragua's Sandinista revolution. The Sandinistas claimed they wanted to address the country's poverty and lack of a democratic process. However, the Sandinista's close diplomatic connection to Cuba and other USSR allies made the U.S. uneasy, says Britannica.

The killers were caught, but the war continued

In response to a stalled investigation, the U.S. embassy's Carl Gettinger took the matter into his own hands. He collaborated with a source inside the Salvadorian military to get a detailed murder confession on tape, writes The Atlantic. A court convicted five Salvadorian national guardsmen in 1984, reports Origins. However, the government released men in the 1990s.

Years of conflict continued, resulting in over 50 massacres and the loss of more than 75,000 lives, primarily non-combatants (via Britannica and Global Sisters Report). Peace talks mediated by the U.N. resulted in the Chapultepec Peace Accords of 1992. However, the conflict and its repercussions reverberate still. Today, murals and monuments adorn Chalatenango and La Libertad, honoring Dorothy Kazel, Jean Donovan, Maura Clarke, and Ita Ford. In Chalatenango, December 2 is a day of remembrance for the women and all Catholic martyrs. Fr. Manuel Acosta told Global Sisters Report, "They left their culture, they left their comfort, and they came here to live the daily life of the poor." The sisters followed in the footsteps of the now-sainted Archbishop Oscar Romero, who said (via Catholic News Agency): "The one who is committed to the poor must run the same fate as the poor, and in El Salvador, we know what the fate of the poor signifies: to disappear, be tortured, to be held captive — and to be found dead."