The Real War That Inspired House Of The Dragon

George R. R. Martin has never been shy about naming his influences. For his ongoing fantasy series, "A Song of Ice and Fire," he's consistently cited an episode in history that inspired him. Though the kernel of "Ice and Fire" came from an image of direwolves in the snow (per the Guardian), the conflict known within the books as the War of the Five Kings took cues from England's Wars of the Roses.

While Martin has been citing the Wars of the Roses as a starting point for years, he's also been keen to put that influence into context. "Some fans have taken that too far and have looked for exact parallels," he told Beatrice, "but none of that really holds up." Martin never intended to tell an allegory of actual English history, with its predestined outcome; rather, he wanted a fantasy epic with the flavor of historical fiction.

Nevertheless, Martin has continued to draw on the Wars of the Roses as "Ice and Fire" expands. Thomas B. Costain's colorful account of the Plantagenet feud was the model for "Fire and Blood," the fictitious history of Westeros's Targaryen kings. But "Fire and Blood" contains within it an account of the Dance of the Dragons, another Westerosi war of succession. With its princess designated heir to the throne, a usurping prince, and divided family loyalties, the Dance draws on an earlier civil war in English history: the Anarchy (per Entertainment Weekly).

The muddied succession to Henry I

The Anarchy was fought between 1135 and 1153 throughout England and the Duchy of Normandy (per History Extra). The Kingdom of England hadn't exactly known peace in the years prior. The Anglo-Saxon kings had been overthrown by William the Conqueror in 1066, and William harshly put down several revolts after taking the throne, according to Britannica. His kingdom and his duchy became spoils for his sons to fight over after his death. Both ultimately came into the hands of his fourth son, Henry I, through intrigue, marriage, and the lifelong imprisonment of Henry's older brother Robert (per Britannica).

After securing England and Normandy under his authority, Henry hoped to establish peace. His efforts to strengthen the state policies and offices of the Conqueror were efficient but brutal, and his devotion to building up his realms over further conquest lasted from 1106 to the end of his reign in 1135. In his son William Adelin, Henry had an undisputed heir. But in 1120, William and an assortment of young nobles drowned when their ship sank on a journey from Normandy to England (per Sky History).

While Henry had other children, William Adelin had been his only legitimate son. His only other legitimate child was his daughter Matilda, one-time wife of the Holy Roman Emperor. Henry recalled Matilda to England, married her to Geoffrey Plantagenet of Anjou, and commanded his nobles to swear oaths of loyalty to her as heir to the throne of England.

Matilda's position was uncertain

As named heir to Henry I, Empress Matilda had more than primogeniture to recommend her for the throne. According to Helen Castor's "She-Wolves," "Matilda inherited her father's commanding temperament, his ability to inspire loyalty, and his political intelligence." Married to Henry V of the Holy Roman Empire in 1110, she spent a number of years as his able regent. Besides her personal and political qualifications, her father engineered two pieces of statecraft theater to ensure his nobles and clergymen gave Matilda their fealty.

But there was no precedent for a woman to be sovereign over all of England, according to History Extra, and while no one at the time claimed that Matilda couldn't be queen, it was an unspoken assumption that colored other grievances. Matilda's second marriage to Geoffrey Plantagenet of Anjou was unpopular with the nobility. Per Historic UK, the Angevins were despised enemies, not future consorts. After two marriages to foreign nobles and long years spent away from England or Normandy, Matilda was perceived as a foreigner herself.

Contemporary or near-contemporary accounts of the empress complain of her haughtiness and controlling nature. Whether this reputation was earned or not, it limited Matilda's support base among the nobility. She and Geoffrey also quarreled with Henry in the last years of the king's life. According to "King Stephen's Reign," Henry was unwilling to yield certain castles that were part of Matilda's dowry, possibly fearing that they were coming for part of his power in his lifetime.

Stephen of Blois, king and oathbreaker

When Henry I died in 1135, his daughter and designated heir, Empress Matilda, was in her husband Geoffrey's home of Anjou (per History Extra). Heavily pregnant, she was in no state to travel to London for a coronation. Nor would she get the opportunity after giving birth; by the time she learned of her father's death, the crown had been usurped by her cousin, Stephen of Blois.

A younger son of Henry's sister Adela according to Historic UK, Stephen had long endeared himself to his uncle and the nobility in a way Matilda never managed. He was a presence at court from a young age, distinguished himself in Henry's struggle to secure Normandy, and was good-looking and good-natured, besides. He was also a dutiful nephew; when Henry commanded that his nobles do homage to Matilda as their future sovereign, Stephen swore his oaths to her.

Stephen had an older brother, Theobald (per History Extra). If Matilda were not to become queen, then Theobald would have the strongest claim to the throne. But Henry had never liked Theobald, and Stephen was well-positioned to claim England. From his coastal lands of Boulogne, he crossed the English Channel and made his way to London for a coronation within three weeks of his uncle's death (per RPI). Conveniently, according to W. L. Warren's "Henry II," a powerful noble swore that Henry had freed all from their oaths to Matilda and named Stephen king on his deathbed.

The king that never was

The line of Henry I did not have a spotless pedigree. Before his father was known as William the Conqueror, he was known by a less-kind sobriquet (per Britannica), based on the fact he was the illegitimate son of Robert I of Normandy. Illegitimacy was not necessarily an impediment to inheritance in the 11th century. William was acknowledged by his father and deemed an acceptable ducal heir, and later king, by his fellow Norman nobles and by the pope, according to Medievalists.

By the time of Henry's death in 1135, mores had changed in England and Normandy. The value of maternal connections in inheritance made legitimacy a more salient issue. Henry had an illegitimate son, Robert of Gloucester, capable and well-loved by his father (per Medievalists). Robert was open about his descent from royalty. But his illegitimacy precluded any serious consideration of Robert as king, so Henry named his daughter Matilda heir.

There's little to indicate that Robert pressed a claim to the throne despite his able stewardship and the significant power he held in his own right, particularly in Wales. After initial resistance, he offered tacit support for his cousin, Stephen of Blois, when Stephen usurped the crown. But by 1138 (per RPI), their relationship had soured. When the two traveled to Normandy to counter an incursion by Matilda's husband Geoffrey of Anjou, Robert seemed loath to counter his brother-in-law's actions. He ultimately renounced Stephen, declared for Matilda, and provided her with an army to invade England.

The powerful friends of both claimants

When civil war came to England in 1135, Stephen of Blois could claim significant advantages and allies. He successfully executed a plan to seize the symbols of kingship, the city of London, and the royal treasury, according to the Medieval Magazine (via Medievalists). Many in the English nobility were already inclined to accept him. And Stephen won the favor of God himself — or, at least his voice on Earth.

While the Archbishop of Canterbury initially favored Matilda, the Bishop of Winchester (by happy coincidence, Stephen's younger brother) spoke on his behalf. Stephen was also able to secure the support of Pope Innocent II in exchange for allowing Rome greater influence in England (per RPI). Promises to the local clergy were reneged on as Stephen's reign went on, and his brother and significant numbers of the clergy turned against him when he arrested the Bishop of Salisbury, but the pope remained in his corner.

Against this, Matilda could depend on her half-brother, Robert of Gloucester, and his considerable strength and popularity with the Anglo-Norman lords in southwest England and the Welsh Marches (per Medievalists). She also had another relative, and a fellow monarch, in her corner: David, King of Scotland. Matilda's mother had been David's sister, and he took up his niece's cause in 1136. It wasn't entirely out of family loyalty; Scotland had a claim to Northumberland, and David hoped to bring it into his realm (per Britannica).

The anarchy came from rebellious nobles

"The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle" describes the Anarchy as a time "[when] Christ slept, and his saints." While Stephen of Blois was a capable and popular man, the dynastic struggle with his cousin Matilda for England proved a challenge beyond his ken. "He was a chivalrous figure — courteous, affable, kindhearted and generous," wrote Elizabeth Hallam in "The Plantagenet Chronicles" (via RPI), but concluded: "He simply lacked the dominant personality essential to successful 12-century kingship."

By alienating the clergy with the arrest of the Bishop of Salisbury, and the nobility with his decrees, Stephen weakened his own support base. Old grievances over lands and incomes from Henry I's reign were pursued as Stephen's government lost control. According to History Extra, nobility and clergy became the unquestioned powers in their local territories and frequently shifted their allegiance depending on the prevailing winds of war.

It is the collapse of centralized authority and the autonomy of the local barons that inspired the phrase "the Anarchy." Some modern writers have challenged the accuracy of that description. "'Anarchy' ... is misleading in the way it suggests a thrilling chaos out of which something startlingly new might emerge," said Kathryn Hughes of the Guardian. "In fact, the years between 1135 and 1153 were more like a long war of attrition during which the country was reduced to tatters." And Edmund King's "The Anarchy of King Stephen's Reign" draws on medieval sources to make clear the scale of lawlessness and devastation of the period.

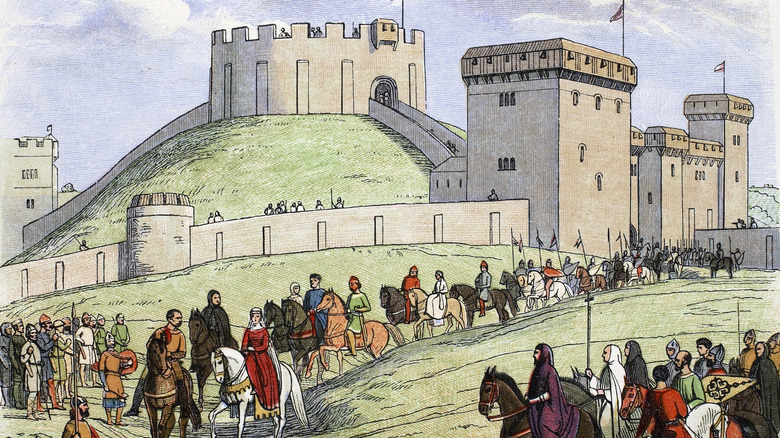

The Battle of Lincoln

A long tradition of romantic literature and epic fantasy films has suggested an image of medieval warfare filled with battles between opposing knights and devastating losses among the foot soldiers. But according to Edmund King's "The Anarchy of King Stephen's Reign," the Anarchy saw many more castle sieges than battles. A good part of the devastation of the war came from besiegers ravaging the countryside to starve out a castle, and from castle garrisons picking their lands clean to starve out besiegers. The goal of most medieval commanders, according to Jim Bradbury's "Stephen and Matilda," was to avoid battles.

During the Anarchy, England saw only one significant pitched battle (per "Stephen and Matilda"): the Battle of Lincoln. A pair of noble brothers had seized the castle in Lincoln over the objections of the local peasantry. When Stephen laid siege to Lincoln, Robert of Gloucester brought an army on Empress Matilda's behalf to meet him. Against advice, Stephen chose to defend the city and met Robert in battle on February 2, 1141. According to RPI, Stephen's forces were greatly outnumbered, and the battle ended in a decisive victory for Matilda's cause. Not only did her soldiers triumph, but Stephen was captured.

He remained a prisoner of his cousin for nine months, according to History Extra. Held in Bristol, Stephen was chained and mistreated. The conditions of his captivity, despite his royal status, damaged Matilda's reputation as she moved to secure the throne.

Londoners rejected the queen

Empress Matilda had been the designated heir of her father, Henry I, and was determined to rule England. While slow to act after her father's death (per the Kirk Center), she and her half-brother Robert of Gloucester mounted a vigorous campaign. By 1141, they had captured King Stephen, and Matilda secured a deal with Stephen's brother to give her support in exchange for church authority, according to the Wiltshire Museum. Styling herself "Lady of England and Normandy," she began to prepare for a coronation at Westminster.

While Matilda's victory over her cousin had strengthened her position in England, control quickly slipped from her hands. According to History Extra, Stephen's treatment while her prisoner weakened her position. She disregarded a tradition for future monarchs to hear petitions in London ahead of their coronation, souring the city on her prospective reign. And forces loyal to Stephen remained near London.

Matilda's coronation was intended for June 24, 1141. Just before it was to begin, an angry mob and the London militia came together against her and assailed Westminster. Matilda was forced to retreat to Oxford. Later that year, Robert was captured during the Rout of Winchester, defending his sister's retreat. To free her brother, Matilda had no choice but to free her cousin and rival in exchange.

The two Matildas

King Stephen's great rival in the Anarchy was his cousin, Empress Matilda, daughter and named heir of Henry I. His great ally was his wife — another Matilda, Matilda of Boulogne. Per History Hit, this Matilda was heiress to the coastal county of Boulogne in France and the feudal lands of the same name in England. Like her counterpart, her marriage was more to do with advantageous wealth and power than love, but unlike the empress and Geoffrey of Anjou, Matilda of Boulogne and Stephen got along well. With Stephen reportedly a genial but unforceful monarch, his wife exercised significant control over events in the Anarchy.

As women, the two Matildas were not permitted to command armies in the field, but they each had a firm hand in organizing their forces and accompanied them at various points in the war. It was an army assembled by Queen Matilda and William of Ypres that surrounded London when Empress Matilda attempted to be crowned sovereign. They would be admitted into the city after Londoners drove the empress to Oxford. Queen Matilda would later summon men from London to relieve the siege of Wolvesey Castle in Winchester.

In what became known as the Rout of Winchester, the two Matildas were once again with their men on opposite sides of the conflict. Queen Matilda's forces forced the empress and King David of Scotland to retreat and captured Robert of Gloucester, forcing Empress Matilda to exchange the captive Stephen for him.

Escaping death, through death

On two occasions during the Anarchy, Empress Matilda nearly fell into enemy hands. On both occasions, she managed to elude capture through desperate measures. Her first escape came when, following her failed coronation expulsion from London, she retreated to Devizes Castle in Wiltshire. Per the Wiltshire Museum, it would become her stronghold for six years. But in 1141, the forces of her cousin King Stephen took the castle. Matilda slipped through their grasp by donning grave clothes, tying herself to a bier, and traveling 60 miles to Gloucester in the guise of a corpse.

A more famous escape, one that has become the stuff of children's bedtime stories according to the Guardian, took place the following year. Matilda had returned to Oxford and found herself besieged. The siege came at a low point in her fortunes; her half-brother Robert, her strongest military ally, was in France, and her husband Geoffrey of Anjou put his adventures in Normandy before his wife's throne. Stephen kept Oxford Castle surrounded for months, and by December, the situation inside the walls was hopeless.

Matilda couldn't hope to withstand the siege any longer, but she wasn't prepared to surrender. In the dead of night, amidst blowing snow, she and a handful of knights donned white and slipped away from the castle, by shimmying down a rope and skating down the Thames if the popular version of the tale can be believed (per Historic UK).

Matilda withdrew to Normandy

After the eventful years of 1141-1142; the capture and exchange of King Stephen and Robert of Gloucester, Empress Matilda's failed coronation, and the Siege of Oxford (per History Extra); the Anarchy reached a stalemate. Matilda held the southwest of England and parts of Wales, with her uncle King David ruling Scotland and her husband Geoffrey of Anjou holding the Duchy of Normandy. Stephen held the east, including London, and retained significant support among the nobility and clergy.

Ruling her territory from Devizes Castle (per History Extra), Matilda established her own mint and went about the business of governing, but neither she nor Stephen could achieve a decisive victory. In 1147, according to the Wiltshire Museum, the Second Crusade began, drawing away many nobles from both sides. The same year, Matilda suffered a major loss when Robert passed away. With his death, the better part of her army was gone. Without her loyal brother — and with growing enmity from the church — Matilda withdrew to Normandy.

After her retreat, Matilda never pursued the English throne again in her own name. But she championed the claim of her son, Henry Plantagenet (per History Today). He was the third Henry in her life, after her father, Henry I, and her first husband, Henry V, Holy Roman Emperor. Upon Matilda's death in 1167, her tombstone was inscribed with: "Great by birth, greater by marriage, greatest in her offspring, here lies the daughter, wife, and mother of Henry."

The Treaty of Winchester

The Anarchy came to an end in 1153. Empress Matilda's son, Henry Plantagenet, had demonstrated his martial and leadership abilities in Normandy and, after an underfunded false start, launched an invasion of England in 1153 to claim the crown that had been denied his mother. According to the Wiltshire Museum, Henry managed to win control of the southwest, the Midlands, and a good portion of the north, while King Stephen fell back to London.

As dramatic an entrance as he had made to England, Henry soon ran into a major roadblock to medieval warfare: his barons wouldn't fight. Neither would Stephen's; after nearly twenty years of civil war, many of the nobility had negotiated peace treaties among themselves to secure their holdings (per History Extra). They encouraged their rival monarchs to do the same, a matter that was made easier by the death of Stephen's son Eustace. In the Treaty of Winchester, Stephen was confirmed King of England, but Matilda's son was named his heir. When Stephen died in 1154, Henry became Henry II of England, the first of the Plantagenet kings.

Matilda remained a valued counselor to her son and was often responsible for governing Normandy in his absences. Henry's long and personally troubled reign nevertheless saw the significant reconstruction of royal authority after the Anarchy, as well as the foundations for modern English Common Law (per Historic UK). Henry would also father two legendary names in English history: Richard the Lionheart and King John.