How Poland Might Have Saved Europe From Communism

When people think of great victories of the 20th century, Poland rarely comes to mind. After all, most are familiar with the crushing defeat the country suffered in 1939 against Germany and the USSR. In 1920, matters looked ally grim as the specter of Bolshevism fell over Europe. Vladimir Lenin, Leon Trotsky, and the other Soviet revolutionaries cast their eyes towards expanding Soviet influence across the whole of Europe in preparation for a global communist revolution.

For all their ambitions, the communists had not counted on the resistance of the newly-formed Republic of Poland. But it would prove their undoing as Poland, against all odds, crushed the Soviets in the Battle of Warsaw in 1920. The story is one of perseverance of a people abandoned by all of Europe who, with their faith in their God, their church, and their country stopped communism cold and ensured that Western democracies would live to fight another day. This is the story of the Miracle on the Vistula.

The rebirth of the White Eagle

When the Republic of Poland confronted the USSR in 1920, it had only been in existence for two years, having been partitioned between Russia, Prussia, and Austria in 1795. Now, by 1918, World War I was over and Russia, Germany (Prussia's successor) and Austria-Hungary (Austria's successor) had all collapsed. These empires' various subject nations asserted their right to self-determination in line with American president Woodrow Wilson's 14 Points.

According to the Adam Mickiewicz Institute, Poland bloodlessly extricated itself from foreign rule. The new republic's army, mostly veterans of the Austro-Hungarian Army's Polish Legions, faced a 30,000-strong German garrison in Warsaw. However, the exhausted Germans wanted to go home, so the Polish Regency Council sent civilians to regale German soldiers with (true) stories of revolution in their homeland. The occupying Germans agreed to an orderly evacuation and disarmament, which was accomplished by November 11. That day, the Central Club of Polish Soldiers declared that Poland once again stood among the brotherhood of nations as an independent country.

Polish marshal Jozef Pilsudski notified the Entente powers of Polish independence in accordance with "democratic principles" on November 16 after a long 123 years of subjugation. But the questions of the new state's boundaries were far from resolved.

The Wild East

When Poland declared independence, its western territories had been part of the German Empire. The Treaty of Versailles passed some of these territories to Poland and fixed the two country's territorial boundaries. The Entente Powers left the question of Poland's eastern borders for a future time. But there was one problem: the Eastern Front of World War I had degenerated into chaos following the 1917 Bolshevik Revolution in Russia and the establishment of the Soviet Union.

As is clear from the Map Archive, while the Treaty of Versailles resolved boundaries in Central and Western Europe, Eastern Europe was a free-for-all. Hungary, Czechoslovakia, and Romania, which either came out of the Austro-Hungarian empire or in the latter case gained its territory, all clashed over disputed areas. The nascent state of Yugoslavia found itself at loggerheads with Italy over the status of the historically-Italian Adriatic coast. Out of Russia came the Baltic states and Finland, which seceded as Russia was engulfed in a bloody civil war between the tsarist Whites and the Bolshevik Reds.

Against such a backdrop, it seemed certain that Poland's eastern borders with the USSR would be drawn not with ink but with blood. And like with many of Poland's past wars involving Russia, the fighting started in Ukraine.

Poland and Ruthenia

According to the Encyclopedia of Ukraine, the hostilities between the USSR and Poland centered primarily over competing claims to Ukrainian territory. Early 20th-century Western Ukraine had a large Polish population, a legacy of centuries of Polish rule. But Ukrainian nationalists also coveted the region, and in the ensuing conflict, Poland captured Galicia and its capital — the cultural jewel of Lviv.

Now, according to Polish History and the EoU, Poland was not opposed to Ukrainian independence. Although Poland intended to establish its pre-1772 Partition borders to include territory that is today part of Ukraine, it was perfectly happy to sponsor an independent Ukrainian state in Central Ukraine (aka right-bank Ukraine) as a bulwark against Bolshevik aggression. So Marshal Jozef Pilsudski pacted with his old enemy, Ukrainian nationalist Simon Petliura, recognizing the Ukrainian People's Republic in return for a renunciation of Ukrainian claims on Polish Galicia.

The alliance initially achieved success, driving the Soviets out of Kiev in 1920. But Petliura's men did not find the expected support among the Ukrainian populace, and a Bolshevik counterattack pushed him and his Polish allies back into Eastern Galicia. The USSR capitalized on its momentum to invade the nascent Polish Republic and capture the capital Warsaw while Polish forces were in Ukraine.

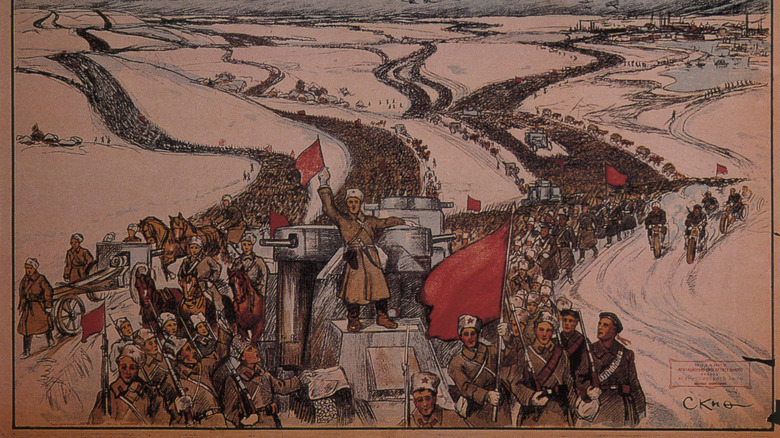

The Red Army invades

The Soviet attack on Poland initially seemed a response to the Polish attack in Ukraine, but according to the Polish National Institute for Remembrance, the Soviets had already been planning an invasion earlier. Attempts to negotiate with Poland were merely attempts to buy time and undermine Polish preparedness. But once Soviet armies shoved Poland out of Ukraine, Soviet general Mikhail Tukhachevsky activated Soviet forces on the Belarussian front and ordered a full-scale invasion in the summer of 1920.

For Poland, the situation had degenerated into a disaster. Jozef Pilsudski had banked on Simon Petliura's Ukraine to act as an anti-Bolshevik wall. But he had not expected Soviet forces to steamroll Ukraine so easily. Now, as the bulk of Poland's forces were in the Southeast, Polish military author and historian Witold Lawrynowicz notes that four Soviet armies totaling 120,000 men rolled into Poland's weakly-defended Northeast. Pilsudski had intended to stabilize Ukraine and bring his forces north to counter the Soviet threat. Now it seemed too late.

At the Battle of Vilnius, Tukhachevsky's forces forced the Poles, who mounted a spirited defense, into a retreat towards Warsaw. Polish artilleryman Stanislaw Rembek (via Niepodległa) described the chaos as Polish forces abandoned equipment, territory, and the dead in a mad rush to escape the advancing Soviets. But not all was lost. Despite foreign propaganda to the contrary, Poland's Catholic bishops and general Jozef Haller noted that the population rallied to the defense of the country. The White Eagle would not go down without a fight.

For the world revolution

So why did the USSR want to invade Poland? According to the Polish National Remembrance Institute, the Bolshevik Revolution did not intend to stop at Russia. In fact, the real Bolshevik target was not Russia — that country was merely a springboard. The prizes were Austria and Germany, the future centers of a "Union of European Proletariat Republics."

Poland literally stood in the way of the USSR's European designs. The revolution could only be accomplished "over the corpse of White Poland." Simply put, Poland had to be crushed to open the way West. Thus, the Soviets began a massive propaganda and logistics campaign, activating the Western European press, leftist politicians, and trade unions to isolate Poland. Thus, war material headed to Poland was diverted both in Germany and Czechoslovakia. The Soviets also established a puppet regime in the northwestern city of Bialystok in anticipation of victory to stir the Polish peasantry and working class against the government in support of the Soviet invasion.

Once Poland fell, Soviet forces in Ukraine were to smash through to Romania, Hungary, and Czechoslovakia — all the way to Italy if necessary. Poland's fall would be the signal for the world communist revolution to begin. As Pope Benedict XV noted, "All of Europe [was] threatened with the atrocities of a new war." Only Polish victory could stop it.

Polish preparations

The Soviet propaganda campaign was wildly successful. Per the National Institute for Remembrance, Britain and France advised Poland to accept Soviet demands, to renounce claims to Ukrainian and Belarusian lands, limit its army to 50,000 men, and effectively become a Soviet puppet. According to Niepodlegla, anti-Polish British Prime Minister David Lloyd George told Poland on August 10 that having rejected the Soviet terms, Poland could expect no help from Britain or anyone else.

The speed of the Soviet invasion and lack of foreign support sent Poland into a flurry of preparations. The northeast was evacuated. Civilian Maria Macieszyna recorded that most civilians believed the Soviets would reach Warsaw and the Vistula River without opposition and were hell-bent on getting West of the city. Warsaw's banks moved their valuables to Krakow or Poznan. The Polish Army stockpiled munitions, took volunteers, and fortified the capital. Now, according to Witold Lawrynowicz, the Polish army had serious problems. Its units were equipped with six weapons produced in as many countries that fired five different types of ammunition. Its logistics were in such shambles that many soldiers did not even have shoes. But they were defending their lands and their faith, and that was enough to motivate them to fight.

Despite Poland's problems, there was a path to victory. Marshal Jozef Pilsudski noted that the key to the Soviet victory was coordination between its armies in Ukraine and those advancing from Belarus. If he could separate the two, they could be defeated separately. But Warsaw had to hang on long enough to make the plan work.

Our Lady of Czecstochowa, pray for us!

According to Witold Lawrynowicz, only two countries stood by Poland. One was Hungary, which attempted to send forces to Poland's aid. The other was the Papacy under Benedict XV. As Pilsudski was organizing the army, the Catholic Church organized civilian support. Per EWTN, Cardinal Achille Ratti (later Pope Pius XI) organized prayer vigils and processions begging God and Our Lady of Czestochowa (aka the Black Madonna) to deliver Poland from the Soviet menace — processions so large that Polish Prime Minister Wincenty Witos (via Niepodległa) complained that they distracted Warsaw's populace from military preparations. Pope Benedict XV, meanwhile, ordered Catholics worldwide to pray for Poland, realizing that if Poland fell, the rest of Europe was probably next.

On the ground, local priests such as Fr. Michal Wozniak held parish drives and collections of anything that could be of military value — from clothing and food to weapons — for the undersupplied Polish Army. Maria Macieszyna noted that in the city of Plock, locals donated their valuables such as gold and silver jewelry, which were then sold to raise money for the war effort. So although Poland was militarily the underdog, the population was determined to give the Soviets the fight of their lives for God and country.

Opposing commanders

To have an idea of the stakes, it is worth revisiting the personalities of the commanders. The Polish army was led by Marshal Jozef Pilsudski. According to the Pilsudski Institute, he had fought against foreign rule since the late 19th century and spent five years in a Siberian labor camp for trying to assassinate Russian czar Alexander III. Ironically, he was also a member of the Polish Socialist Party. He acquired military experience during World War I from service in the Austro-Hungarian Polish legion, hoping that in return for Polish aid against Russia, Austria-Hungary would support Polish independence. Now the temporary head of state, Pilsudski faced the monumental task of fending off the massive Soviet invasion commanded by the brilliant but eccentric Russian general Mikhail Tukhachevsky.

Tukhachevsky, unlike Pilsudski, was a Russian aristocrat, who per the Revue historique des armées, had joined Bolshevism upon his release from a Central Powers POW camp. There he was cellmates with future president Charles de Gaulle and French journalist Remy Roure, who wrote of his time with Tukhachevsky. According to Roure (via Sergei Minakov's "Red Conspiracy") Tukhachevsky was a neo-pagan acolyte of the Slavic storm god Perun. While his cellmates believed it a joke, Tukhachevsky despised Christianity, claiming the faith had sapped Russia of its strength. Marxism provided a new religion, but with its materialist bent, could never restore Russia's true spirit. Only the old gods could. Marxism, with all its violence, death, and suffering, was the perfect vehicle to crush Christianity in preparation for Tukhachevsky's vision. The Catholic fortress of Poland would be his first victim.

The Soviet attack

As Witold Lawrynowicz writes, the Soviets attacked Warsaw from the north and east on August 13. For Tukhachevsky, it was personal. His great-grandfather had spearheaded the exact same maneuver against Warsaw to defeat the 1831 Polish Uprising and he was eager to cover himself and his family in glory again. Tukhachevsky's main force in the north met with resounding success at first. The Polish defense of the town of Radzymin crumbled. The Soviets could now see Warsaw's spires. Writer Maria Dabrowska (via Niepodlegla) recalled that the city seemed so serene in the summer weather and yet so poor as rural refugees and their many animals flooded the city amidst the rumble of Soviet artillery shelling the city. According to EWTN, however, Cardinal Achille Ratti continued to lead Eucharistic processions even at the risk of his own life to bolster the civilian morale in hopes of a miracle.

Despite the initial success, however, all was not well in the Soviet command. Tukhachevsky had hoped to use forces under Semeon Budionny to encircle Warsaw from the South. But a certain Soviet commissar named Joseph Stalin disliked Tukhachevsky and urged Budionny to go East and capture the Galician city of Lviv instead. This maneuver seemed inconsequential at the time. Tukhachevsky's forces still had overwhelming superiority over the Poles. But it would prove a costly failure once Polish forces managed to counterattack.

The Miracle on the Vistula

Despite Joseph Stalin's insubordination, the Soviet assault continued to gain ground. Per Witold Ławrynowicz, the Soviets advanced all the way to the village of Izabelin and were a mere eight miles from Warsaw proper. By August 15, Pilsudski was still massing his reinforcements in southern Poland and had not yet arrived, leaving the capital in a mood of desperation.

Enter the supernatural. Per EWTN, August 15 was also an auspicious day, for it was the Feast of the Assumption of the Virgin Mary. As Soviet forces pushed the Poles further into the capital, rumors began to circulate that a lady holding a child had appeared over the Polish lines and Warsaw itself. Inspired by rumors of divine intervention of Our Lady of Czestochowa, Polish forces counterattacked. Military chaplain Ignacy Skorupta, per the Institute of National Remembrance, died with the cross in hand urging the men forward in an epitome of the Polish cause. His death would not be in vain. Soviet rifleman Vitovt Putna (via Niepodlegla) recalled on the 15th, "A moment came when not just single units, but the entire mass lost faith in the success of our fight against the enemy, faith in our chance to win." Soviet forces began to fall back, handing Poland the initiative.

The Polish counterattack

The dogged defense of Warsaw brought three days of relief to the city, but the Polish high command still needed Jozef Pilsudski's forces to break the siege and begged him to march forth — even if he was not ready. According to the Institute of National Remembrance, Pilsudski assented and began a counteroffensive from the Southeast early on August 16.

Per Witold Lawrynowicz, the Polish marshal had expected to encounter robust Soviet resistance under Semeon Budionny. But Budionny had decided to head to Lviv, leaving a gap between the Soviet forces besieging Warsaw and those in southeastern Poland and western Ukraine. Only a single infantry division called the Mozyrska Group guarded the gap. Polish forces steamrolled the unit and then broke the Soviet 16th Army's (the army directly East of Warsaw) flank and routed it. The Polish Legion pursued it all the way to Bialystok, marching 163 miles in six days for up to 21 hours at once, and captured the army in its entirety.

With the Soviet forces east of Warsaw dispersed, Polish forces attacked the units North of Warsaw from the East and blocked their line of retreat back into Soviet territory. The Soviets were left with two options: fight Poland or retreat into Germany. They chose the latter, where the local authorities disarmed them. Poland's victory was complete and Tukhachevsky humiliated.

Aftermath

The Soviet casualty list was catastrophic. According to the Institute of National Remembrance, Poland captured 66,000 Soviet soldiers. 25,000 more were killed, while another 50,000 more were taken prisoner in Germany. Witold Lawrynowicz adds to that total 231 guns and 1,023 machine guns, which fell into Polish hands.

Despite the victory in Warsaw, fighting continued in Western Ukraine, where Polish forces were holed up in Lviv. Per the Institute of National Remembrance, Semeon Budionny, who had abandoned his post at Warsaw to capture Lviv, encountered a Polish battalion of 330 men. Despite numerical inferiority, the Poles won the Battle of Zadworze, which earned the moniker "the Polish Thermopylae” after the famous last stand of the 300 Spartans of Greek lore.

The fighting finally ended with the 1921 Treaty of Riga. Article II handed Poland Western Ukraine and Belarus alongside a payment of 30 million gold rubles. The latter served as an indemnity for Poland's economic contribution to the Russian Empire. As the Hungarian Review notes, it was a humiliation the Soviets would not forget. And dictator Joseph Stalin, whose actions had in part led to the Soviet defeat, would exact a brutal revenge in 1939-'40, first with the invasion of Poland and then with the massacre of the Polish officer corps and intelligentsia in the Katyn Forest — many of whom had fought at Warsaw.

An auspicious birth

Three months before the Soviet invasion, a baby was born in the Polish village of Katowice. His parents baptized him Karol. According to EWTN, this man "since [his] birth ... carried the great debt toward those who died fighting against the aggressor and who won, giving their lives for their country." Karol would later become Pope John Paul II, archenemy of Soviet communism.

As the Hungarian Review notes, without the Battle of Warsaw, there may never have been a Pope John Paul II to continue the anti-communist crusade that eventually collapsed the Soviet Eastern Bloc. The pontiff noted that the circumstances of his birth instilled in him a pride in his homeland and respect for its fallen, which in turn allowed him to respect and admire the others' love of their own history, culture, and ancestry.

In 1980, he told UNESCO, "I am the son of a nation which has lived the greatest experiences of history, which its neighbors have condemned to death several times, but which has survived and remained itself. It has kept its identity, and it has kept, in spite of partitions and foreign occupations, its national sovereignty, not relying on the resources of physical power, but solely relying on its culture." That culture and its Catholic underpinnings, the pontiff suggested, inspired Poles to fight Bolshevism even when all seemed lost. From this angle, the Battle of Warsaw truly deserves to be called "The Miracle of the Vistula."