The Untold History Of Swing Music

As the nation became more connected in the 1930s, crossroad cities like Kansas City and Dallas became cultural meeting points for musical styles. If you took a trip across the country back then, that usually meant you would have to cross through these cities, and it was in these places where traveling musicians would settle and share their talents with each other, as laid out in a timeline offered by Carnegie Hall.

These groups formed what would be known as the "big bands" of jazz, and their orchestral combinations of instruments would become the standard for jazz music. Big bands flourished in the Harlem Renaissance, which spread Black culture in the arts across the country. With the influence of big bands like those led by Louis Armstrong, a swing music started to form and took the country by storm.

Swing music dominated the 1930s to 1945 music scene. As explained by Carnegie Hall, swing music gets its name from the beat of the notes themselves — the second and fourth beats in the melody get a emphasized and the steady eighth notes become lighter, swinging notes. This movement in the music creates a beat that gives the audience a feeling of movement. Swing became inseparable from its dances, to which the music owes much of its popularity.

Advancements in technology helped birth swing music

Swing music was a nationwide craze, and it could not have reached national appeal if it were not for the significant developments in transportation and communication made in the early 20th century. The sounds of New Orleans-style jazz were what first inspired the first type of music to be commonly classified as swing music, but this sound traveled north along the then popular steamboats that floated up and down the Mississippi River, as acousticmusic.org details. The sound of swing music comes from the "big band" era of jazz, and these large groups would regularly book gigs on steamboats, bringing the southern sound of swing music to the north.

Spreading music even further was the surging popularity of the home radio. By the mid 1930s, the United States was firmly within its "Golden Age of the Radio," as it became known. According to PBS, the 1930s saw a boom in the amount of home radios across the country, rocketing from 12 million at the start of the decade to 28 million homes with radios by the end of the decade.

Advances in recording technology also resulted in the development of the Jukebox in 1933, keeping the music going from home to out on the town as well, acousticmusic.org notes. Whether watching live music, relaxing at home, or going out, technologies of the time kept swing music constantly within the consciousness of the American people.

Early developments in swing weren't popular with critics, but fans didn't care

While most people were putting another dime in the jukebox and turning up the volume dials on their radios, the critics were penning poor reviews of swing music from the start.

Much of this criticism was directed towards Louis Armstrong and his shift towards the big band style of jazz in the early '30s. Armstrong and his band had a profound influence on the development of swing music, and many of the aspects that made their new sound influential were what critics hounded them for.

Author of the Louis Armstrong biography, "What a Wonderful World," Ricky Riccardi, explains this criticism in an interview with Indiana Public Media: "In the 1930s, Louis Armstrong becomes a superstar, and he's leading this big band, and he's breaking down barriers, and he's conquering all these mediums, and there's this very small but vocal segment of the jazz critics out there saying 'this guy's gone commercial ... if only we could get the sincere artist of a few years ago.' And that starts around 1932 or 1933 and doesn't end for the rest of his life."

Even with the critical review labeling swing bands as soullessly commercial, the sound was popular with crowds nonetheless. One example is found in the 1932 tour of the Moten band, who reportedly performed seven encores at their Philadelphia performance, according to the book, "One O'Clock Hop," by historian and professor Douglas H. Daniels.

Swing wouldn't have been as popular without breaking down racial barriers

Swing music's roots come from African-American Jazz roots in New Orleans, as acousticmusic.org notes, but the sound and dance associated with it were so infectious that people of all races and cultures enjoyed and celebrated it.

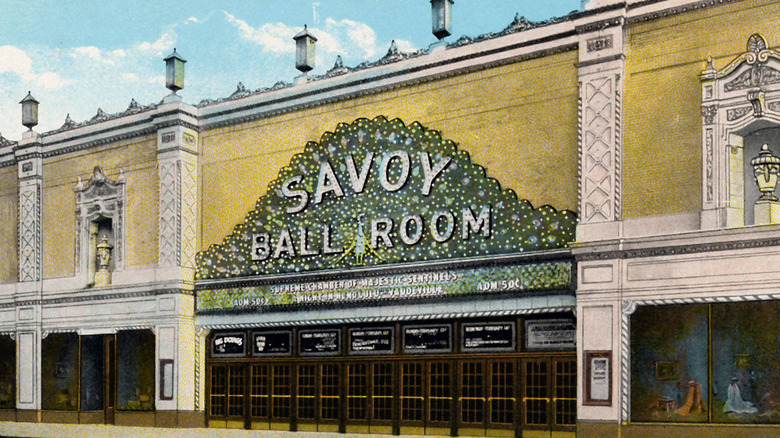

The success of swing music in breaking down the barriers of early 20th century segregation was shown best at the Savoy Ballroom. In the early to mid 1920s, the most popular night clubs in Harlem were segregated spaces where Black bands were performing for white audiences, Christi Jay Wells, an assistant professor of musicology at Arizona State University, explains in a lecture to the Frankie Manning Foundation. The Savoy Ballroom "was to serve as a sort of uptown version of these segregated downtown venues like the Roseland Ballroom, and it contested these policies by offering a vision of utopian integration, where people of all races and circumstances were welcomed."

Swing and Lindy Hop star Frankie Manning noted that at the Savoy Ballroom you were judged only based on your dancing ability, not the color of your skin. He was even quoted as saying, "All they wanted to know when you came into the Savoy was, do you dance?" This was ostensibly true at the Savoy Ballroom, with mixed-race crowds every night of the week that even reached a 50/50 split at some times, according to Harlem World Magazine.

The king of swing risked his career on swing music

While certainly not the father of swing music, Benny Goodman rose to fame as the "king" of swing music, becoming the first artist to perform a swing concert in Carnegie Hall, according to reporting by NPR. According to the curator of jazz at Lincoln Center, Phil Schaap (via NPR), that concert became the most important performance in not just swing music's history but for the history of jazz as a whole.

The critics at Carnegie Hall were not interested in jazz as a genre, and especially not interested in new directions jazz was taking. As Schaap puts it, "[Goodman] was risking some very bad reviews, since the music critics at the time were not jazz people. You didn't have a jazz critic at a publication. You had a music critic who probably was on the record saying jazz was junk."

Goodman took swing music onto the big stage into a venue filled with these kinds of pretentious critics. For Goodman, it was a big risk when his career was already going well, but the reward ended up being even bigger. The concert was a massive success, and he was invited back a few months later and again the next year, cementing his title as the "King of Swing."

Some Jazz bands experimented with Conga drums and Maracas

Jazz and swing music have a history of breaking down racial barriers and mixing cultures, and that was especially true in the late 1930s when the Afro-Cuban movement started to influence jazz and swing music.

According to a timeline offered by Carnegie Hall, the migration of Cuban and Puerto Rican populations to New York meant the development of new music and dance interests in America's largest melting pot. Around this time, dances like the rhumba started to develop, and with new dances had to come new music.

Afro-Cuban musicians such as Mario Bauzá, Tito Puente, and Chano Pozo lead the development of jazz style swing music with Latin instruments. They primarily relied on percussion instruments like maracas, claves, and even conga drums to highlight the rhythmic nature of their sound.

According to reporting by Stanford Live, big band orchestras incorporated these Latin rhythms into their sound, and dances like the rhumba and the conga became a part of swing music as well. By the close of the 1930s, the Afro-Cuban style of swing music moved off into its own direction. Afro-Cuban jazz solidified its own sound starting with Bauzá's "Tanga," composed in 1943, which would inspire more Afro-Cuban jazz after swing music started to fade.

Swing fans were obsessed with new dance crazes

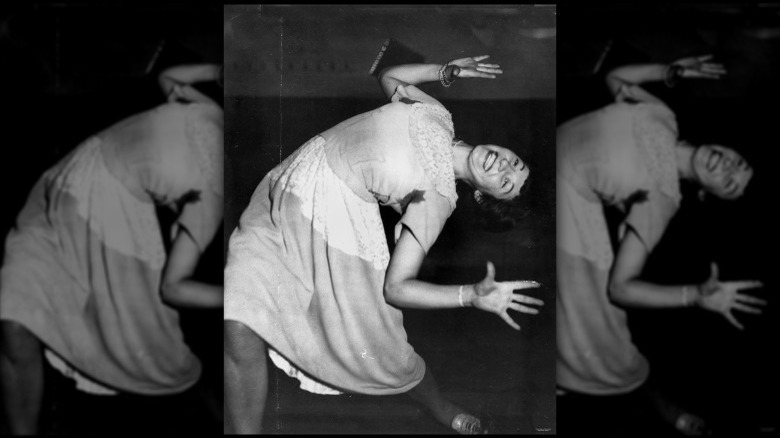

Swing music cannot be separated from the popularity of the dances that became associated with it. The swinging movement of the notes, which gives swing its name, is meant to get its listeners up and moving.

The movement of the music was meant to be felt by the listeners, and as Louis Armstrong put it (via Carnegie Hall), "If you don't feel it, you'll never know it." That "feeling" is what got people dancing in styles like the Lindy Hop and the Jitterbug. The Arthur Murray Dance Center lists a number of other swing style dances such as the Charleston, the Collegiate Shag, East and West Coast swing, and Balboa.

While a range of swing styles exist today, and swing dance competitions continue to be held by the U.S. Open Swing Dance Championship, the development of these styles find their origins at the Savoy Ballroom in Harlem back in the 1930s. The Lindy Hop, the Flying Charleston, Jive, Snakehips, and Rhumboogie were all conceived at the Savoy Ballroom, according to Harlem World Magazine.

Dancers remained in constant competition with each other at the Savoy Ballroom, with the northeast section of the dance floor, nicknamed "the corner," committed to the most experienced and competitive dancers.

Swing's most popular dance was named seemingly by chance

The most popular form of swing dancing, both back in the 1930s and today, is the Lindy Hop. According to the Chicago Swing Dance Society, the Lindy Hop was invented by African-American kids in Harlem as an improvisational form of dance with steps following the beat of swing music as its foundation.

The Lindy Hop is a folk dance, formed out of a collective group of people's reaction to swing music, so naturally it did not have a name when the earliest Lindy Hoppers were on the dance floor. It was not until reporting about swing dance and swing competitions took hold in the media that Lindy the Hop gained its name.

In 1928, the Lindy Hop took the grand stage at an endurance dance competition at the Manhattan Casino where dancers competed for a $1,000 prize (about $17,000 in today's money).

Reporting in The Evening World (via Savoy Style) about Mattie Purnell and George Snowden dancing at the competition is where the first printing of the Lindy Hop's name can be found. Snowden allegedly was responsible for the name, after he had seen a newspaper headline titled "Lindburgh Hops the Atlantic” one year earlier.

Jazz legend Ella Fitzgerald was legally adopted and partly raised by a swing band

Ella Fitzgerald was one of the all-time great jazz vocalists, and she shined during the swing era, where she saw much of her rise to fame. According to AllMusic, Fitzgerald was only just entering adulthood in 1935, during the height of the swing era, but she already was finding incredible success.

After she won a talent contest at the Apollo Theater, jazz drumming star Chick Webb took notice of her abilities and offered her a chance to perform in his orchestra. Fitzgerald was a perfect fit for the band, with them accepting her as family almost immediately, and with Webb legally adopting her not long after.

Fitzgerald lived her early adulthood touring with Webb's band, which he reorganized and restructured to focus on highlighting Fitzgerald's abilities, making her the star. According to AllMusic, Fitzgerald's voice and abilities led to his highest selling record in 1938, "A Tisket-A-Tasket."

Webb met his untimely death in 1939 due to complications with surgery treating his congenital spinal tuberculosis, and Fitzgerald carried the torch, leading the band through to the end of the swing era. In 1941, like many swing music artists did, Fitzgerald left the band to start her own solo career.

A diverse, all-woman swing band was nearly erased from history

Well known at the time — but not as much celebrated in common tellings of jazz history — were The International Sweethearts of Rhythm, an all-women, racially diverse swing band that thrived despite adversity during a time of segregation in the United States. The Sweethearts played at some of the largest venues in the country, but their success was not well documented, according to reporting by The Guardian.

Rosalind Cron, one of the members of The Sweethearts, explained how they were snubbed, citing exclusion from the white press and recording offers being denied to women, especially Black women, in the '40s.

The band was composed of mainly young women who grew up as orphans together at the Piney Woods school outside of Jackson, Mississippi, and their band started as a way to fundraise for the Piney Woods school.

The band was an instant success, even touring with the USO, where they challenged segregation ideals and laws across the country. Cron was even arrested in several southern states for violating segregation laws that tried to prevent her band from existing. The Sweethearts continued their touring until the end of World War II.

Artists shifted away from swing even though fans wanted more

Swing was a strong craze, both as music and a dance form, but like all crazes, the hype eventually died down. In swing music's case, however, it was not the public getting tired of it that moved it out of the public's perception. Listeners continued to want more as the swing era came to a close, but artists moved on anyway.

According to Jazzed Magazine, artists did not tend to find swing music as creatively and professionally fulfilling as other jazz music. Swing had immense commercial appeal, but the big band style meant that individual artists in a group had more difficulty making a name for themselves.

Artists shifted to bebop, an improvisational style of jazz that focused on diverse sound and lacked vocals, and the shift was sudden. Audiences no longer had predictable melodies to dance to, and the music was enjoyed for the music itself, rather than the movements associated with it.

Every aspect of jazz changed: the sounds, the size of the band, even how the artists dressed changed when the swing era ended. The shift was a sudden revolution in the music of the day and a dramatic shift from a commercially friendly, dance heavy genre, to a type of music that was often imperceptible to listeners.

Swing found an unexpected '90s revival

Perhaps one of the most unexpected sources caused a brief revival of swing music in the late '90's: a Gap commercial for khakis. While not the only thing that started the renewed interest in swing, this commercial was playing on repeat just before two hit swing singles hit the charts, according to Billboard.

These sources jolted a reminder into the nation's consciousness, and people were interested in swing again with a few bands like Squirrel Nut Zippers capitalizing on it. Media even continued the fixation in other forms with the 1996 Movie "Swingers."

But if the '30s swing era is what could be considered a swing craze, then the interest in swing in the '90s was no more than a fad. According to Billboard, as soon as the 2000s hit, the public interest in swing dwindled to nothing, and swing was dropped just as quickly as it had been picked up.

Contrasted from the end of the swing era in the '30s was the loss of interest by the public causing the decline in the '90s. Rather than artists forcing the change in musical stylings, the public's loss of interest is what triggered the disinterest in swing moving into the 2000s.

Electro swing attempted to revive swing to mixed reviews

Electro swing started as a small trend in Europe starting around 2009, and is growing in popularity even to this day. European bands started to take the swing style of American '30s and add the sounds of electronic music.

Reporting during its rise in 2013 by NPR points to a 1994 song by the rapper Lucas titled "Lucas With the Lid Off" as the first precursor to the electro swing trend that took hold in the 2010s. Its popularity took off starting in 2009 with the anthology collection "White Mink: Black Cotton," which contrasted electro swing and classic jazz by including both types of music on back to back tracks.

Repeating history, critics once again did not respond very well to electro swing, with Vice publishing an article with the rather dramatic title, "Electro Swing is the Worst Genre of Music in the World Ever."

Despite this criticism, much like in the original swing era, the audience took strongly to the music anyway. In fact, just one month before Vice's article was published, Caravan Palace's "Lone Digger" was released, which has now garnered over 300 million views and over 3 million likes.