The Untold Truth Of Atari

Atari. The name makes you think of "Pong" (inevitably), "Tank," "Centipede," "Space Invaders," and "Asteroids," among many other arcade and console games. How did the brand spawn, and why did it crash?

What was once the video game company to end all video game companies was born from the ambitions of visionary engineer Nolan Bushnell. He was into games as far back as he could remember and had a fascination with science, according to Game Developer. Bushnell grew up creating electric contraptions. In college, after playing hours of "Spacewar!" on a primitive computer and manning carnival games over the summers, he imagined that someday, digital screens would replace the pinball machines he saw in the arcades of the 1960s. Bushnell fantasized about being a Disney Imagineer after he saw just how magical it was when animatronics and other technology were used to create entertainment. He instead started out designing computer graphics in Silicon Valley and was soon creating his own video games, teaming up with a few fellow engineers who would help him take that tech to the next level. Atari was born.

"Nolan designed these incredibly elegant circuits put together in a way that's so clever that modern engineers have a hard time understanding and repairing these things," Seamus Blackley, co-creator of the Xbox, says in the documentary "Atari: Game Over." Press "play" to see just how much Atari revolutionized gaming.

Atari got its name for a reason

https://www.grunge.com/929429/...Atari was the brainchild of three engineers with a clunky TV and a dream. They had no idea that the programs they were tinkering with would revolutionize gaming forever.

The company name was originally supposed to be Syzygy, which means an alignment of three celestial bodies. It was something Nolan Bushnell randomly flipped to in the dictionary. However space-age it sounded, copyright issues forced him to look elsewhere, according to Game Developer. He turned to his college memories of playing the strategy game Go, which had been popular in Japan for thousands of years. This deceptively simple game literally has trillions of possible outcomes. Bushnell chose the Go gameplay term "Atari" because he liked its threatening translation: "You are about to be engulfed." Even the official logo appears to be a mashup of the letter "A" and Mount Fuji, and its nickname of "Fuji" was a throwback to the inspiration that spawned Atari.

Creating their own video games wasn't going to be Atari's main business. As one of the early developers for Atari, Allan Alcorn (who would later invent the iconic "Pong"), remembers in a memoir of his time with Bushnell and Atari, "Our mission ... was to be an engineering consulting firm and receive royalty checks." Along with partner Ted Dabney, Alcorn and Bushnell built pinball machines and designed games for companies that contracted them. That was all about to change drastically.

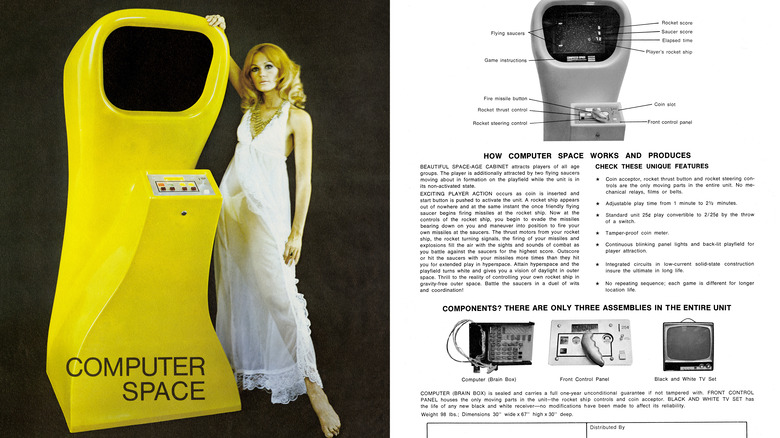

Its first game, Computer Space, didn't really take off

The brains behind Atari started out in a makeshift computer lab with a treasure trove of odds and ends they could convert into working machines. It was hardly a science fiction movie set.

As Atari engineer Allan Alcorn recalls in his memoir, what frustrated Nolan Bushnell about how computers were used in video games at the time was that the entire machine was really just figuring out which way objects in the game were going. To reduce costs, Bushnell ditched the computer altogether and instead used a nearly obsolete vacuum tube TV to create his own. The result was something close to the lone existing video game at the time, "Spacewar!" Bushnell's version, which he named "Computer Space," was a retro-futuristic machine that was basically a TV in a fiberglass case.

"Computer Space" emerged from Bushnell's daughter's bedroom (which had been used as a lab) in 1971, as Game Developer reports. Gone was the assumption that a video game would need thousands of dollars' worth of hardware. Bushnell and his partners had turned an old TV and about a hundred dollars' worth of parts into a functioning video game, and the way Bushnell simplified the technology influenced the gaming industry during the '70s. "Computer Space" itself hardly got off the ground after it was sold to Nutting Associates that same year. Players were confused by both the game and the controls, and while Bushnell tried to revive it, he went searching for ideas elsewhere.

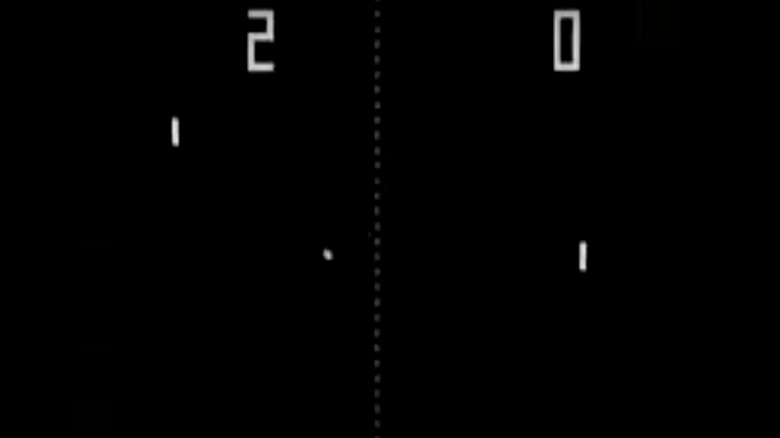

Pong was almost not released

When "Pong" was originally developed by Allan Alcorn (pictured), it was not meant for commercial release. The now-iconic game that still shows up today in nostalgic arcade bars was just supposed to be a performance test and job practice for him, but it ended up becoming the company's flagship game.

When Alcorn was developing "Pong," Atari had something no one else did: the motion circuit. Nolan Bushnell had come up with the technology while he was creating "Computer Space," which had been a commercial failure. "The idea was to make this spot, this ball, address all the different locations on the screen, when there is no memory," Alcorn said in his memoir, describing Bushnell's innovation. "It was a very clever trick using a variation of a synch generator circuit." Alcorn used the technology for "Pong" in 1972, but he had another big challenge to overcome: Bushnell had instructed him to create "Pong" with parts that would cost no more than $15 (about $108 today).

"Pong" only used a few component parts, along with a digital method of keeping score and some rudimentary sounds. Alcorn exceeded his budget, and since Bushnell never told him the game wasn't really meant for production, Alcorn considered his prototype a failure. But Bushnell thought the game was playable, so they decided to test-market it at a local pub. According to the National Museum of American History, "Pong" made its debut at a bar in Sunnyvale, California, and went viral before going viral was even a thing. So many people played this first "Pong" machine that it broke down because it was jammed with quarters.

Almost no one thought Pong would be profitable

Even though "Pong" was a hit at that bar, with people showing up just to have a shot at beating it, Game Developer says no one wanted to mass-produce the game. "Pong" was turned down over and over by game manufacturers because the companies didn't understand the game's appeal. Bushnell packed up a portable version of "Pong" and set out looking for buyers in the fall of 1972, with his first stop being Bally, which had already enlisted Atari to create a driving game. The problem was that Bally didn't want to take a risk on something that required two players. When Bushnell took the "Pong" machine to the Amusement and Music Operators Association trade show, every potential manufacturer he approached refused to take it on because they did not understand it. This was what led Bushnell to turn Atari into a game manufacturer.

As Atari co-founder Ted Dabney told the Computer History Museum, he, Bushnell, and Allan Alcorn were doubtful they would be able to build "Pong" machines themselves. They thought there was no way they could afford all of the parts that went into it. "I said, 'Wait a minute, wait a minute. We're not talking about that,'" Dabney remembered. "'We're talking about with our decision. [Are] we gonna go home or are we gonna manufacture it ourselves?' Well, nobody wanted to go home."

After they decided to venture into manufacturing, the Atari team split up who bought what parts, from PC boards to TV sets for the screens. Dabney had to pay for the TV sets himself since the company was broke.

Pong was loosely inspired by a Magnavox game

Rewind to earlier in 1972, when "Computer Space" had crashed hard in the market and Bushnell sought out more inspiration. One of the places he found it was a Magnavox product showcase.

That summer, as Thinkset Magazine reports, Magnavox released a game system called the Odyssey. It was the dawn of the home video game console. Engineer Ralph Baer had thought of a way to play video games on a repurposed TV. Just a year before "Pong" madness hit, Baer filed the world's first video game patent. Baer's creation was licensed to Magnavox, which included "Table Tennis" as part of Odyssey's roster of games. "Table Tennis" was eerily similar to "Pong," but it had its glitches. When Bushnell played Magnavox's game, he wasn't impressed by the execution, but the concept of a ping-pong video game stuck with him, according to Game Developer.

Odyssey had some success, but it was nowhere near the meteoric rise that "Pong" experienced after Bushnell decided that Atari would manufacture the game itself. The thing that made Atari's version more lucrative in the end was that "Pong" was released as a coin-op machine for bars and arcades rather than a more expensive home console. Anyone who managed to scrounge up a quarter could play. Wired reports that Odyssey cost a staggering $100 by comparison (the equivalent of about $707 as of August 2022).

Magnavox sued Atari because they thought they really created Pong

It might seem like Bushnell was out for a cash grab, but that was not the case. The University of Georgia Law School Journal of Intellectual Property Law documents this in the study "Copy Game for High Score." The author points out that "Table Tennis" had no sound and didn't even offer its players a way to keep score. "Pong," on the other hand, seemed fun and engaging to Bushnell, so he and Ted Dabney decided to sell it instead of chalking it up as practice.

Rather than copy "Table Tennis," what Bushnell really wanted to do was create a game that had what "Table Tennis" lacked. (Al Alcorn, who developed "Pong" for Atari, had never seen "Table Tennis.") Still, Magnavox sued Atari for patent infringement in 1974, as Thinkset Magazine reports. They also sued several other companies that knocked off "Pong" from Atari, since they believed "Pong" was derived from their products. Their argument was that the patent protected the tech that made it possible to play the game. Atari eventually settled for $1.5 million and had to license the Magnavox technology to keep earning a profit off "Pong."

Gran Trak 10, the first racing game ever, was inspired by a math game

Atari's driving simulation game "Gran Trak 10" may be the predecessor of all racing games — per US Gamer, it was not only the first game that put you in the driver's seat, but also the first that featured a steering wheel and let you accelerate, shift gears, and slam on the brakes. But it got its engine from the pages of a science magazine.

"Gran Trak 10" was the digital version of "Racetrack," a game published in a 1973 issue of Scientific American, according to Alexander Smith in his book "They Create Worlds." You needed a pen and paper to play "Racetrack," so you could use math to figure out how cars would maneuver around the curves of a track. "Gran Trak 10" sped ahead of more primitive games like "Pong" because it needed to display not just dots and scores but an entire racetrack, which was a monster graphic back then. It needed more ROM (read-only memory) than existing circuit boards could handle. To provide all that memory, a ROM chip was created for Atari by the company Electronic Arrays.

To prevent those ROM chips from being copied, US Gamer reports that Atari would label them with part numbers from Texas Instruments calculator parts, so anyone who dissected the game and thought they could order that exact part would be frustrated when they received something that was incompatible. Putting the wrong chip in the socket would make it crash.

Atari secretly created their own competitor

Atari had something covetable, and other companies were breeding "Pong" clones faster than quarters were jamming the slots. Nolan Bushnell dreamed up an unconventional solution for that.

Atari was somewhere in the middle of being sued on one end and copied on another when they released "Gran Trak 10," according to Charlie Fish in his book "The History of Video Games." To add to the burden of the Magnavox lawsuit, something glitched in accounting, and "Gran Trak 10" was so underpriced that Atari lost $100 on every unit it sold. They had also tried and failed to get in on the Japanese market, so the company was bleeding money.

Before Atari became a fatality in the video game sphere, Bushnell created Kee Games as a direct "competitor." Anything with Kee branding was really just an Atari game in cosplay. It worked, because distributors had no idea what was really going on behind the scenes and fought over the rights to sell these games. Atari was able to sell double the games, because they were essentially selling the same game twice to competing distributors, with different names and packaging. "Tank" was released by Kee in 1974, beating "Pong' in sales and saving Atari from looming bankruptcy. Kee finally merged with Atari in 1975, per Game Developer.

Atari was sold to Warner Communications, but Warner screwed up

By the late '70s, Atari was having trouble leveling up. As a 1976 New York Times article officially announced, Warner bought Atari for $28 million. The contract stated that the transaction meant Atari would be a subsidiary of Warner, and top managers at Atari would keep their positions. Atari was also in the process of moving its headquarters to Sunnyvale, California, at the time. Another New York Times article published a few weeks later confirms the completion of what it calls the "Atari takeover."

Unfortunately, Warner, for all its entertainment clout, had no idea how to run a Silicon Valley business. Allan Alcorn mentions being frustrated by the acquisition in his Atari memoir. Atari was desperate because sales were at a standstill, but Warner didn't realize what would happen when the worlds of mainstream corporate culture and Silicon Valley collided. "In Silicon Valley, what we were doing was not normal business," Allcorn said. "It was a very hit-driven technology business. You had to eat your own young because if you didn't, somebody else would."

Warner didn't know how to upgrade constantly in order to keep up with the ever-developing video game industry. Though they bought Atari because they saw huge potential, and their assets allowed Atari to do more research and development than ever, they mostly failed to grasp the essence of Silicon Valley. However, the merger gave Atari the influx of money it needed to start its next venture: a home console.

The Atari 2600 revolutionized gaming

The Atari 2600 — otherwise known as the Atari VCS — is a fossil by today's console standards, but it's an iconic piece of '70s and '80s gaming technology. Allan Alcorn remembers it as being a breakthrough like no other. "It was really brilliant," he says in his memoir. "It was totally different from where everybody else was going."

The VCS (Video Computer System) was prototyped by engineers Steve Mayer and Ron Milner in just three months. Atari ran a lab for research and development in Grass Valley, California, according to Allcorn. Milner and Mayer worked in that lab and came up with the embryonic VCS in 1975, and Mayer developed the first software for it. It technically qualified as a computer, though it had limited memory and no keyboard.

The VCS didn't see an instant win on the market when it was released in 1977, but neither had other early consoles. Atari's merger with Warner Communications gave the console the advertising budget it needed to fly off the shelves within a few years. It could be connected to a TV and initially came with one game cartridge, two joysticks, and two paddle controllers. Eight other games were released at the same time, and some got fancier with the controls. "Indy 500," for instance, was an upgraded driving game with two steering wheels, so you and a friend could take the literal wheel at home.

Soon, Atari was getting into computers

Video games were really taking off in the late '70s, even though the Atari 2600 had a slow start, but computer games were creeping up on them. Atari wanted to get in on that.

Several years earlier, one of Allan Alcorn's employees at Atari was none other than Steve Jobs, as al Alcorn recalls in his memoir. Jobs wanted to create a home computer, but Alcorn and the others weren't interested in his ideas — they were focused on gaming. Eventually, though, Atari did develop a home computer. "We, the engineers, wanted to do it because we already knew how to do custom chips," Alcorn said. "None of these other personal computer manufacturers could do custom chips, and we were pretty good at this."

Atari moonlighted in the computer industry for about 15 years. They saw what had happened with Apple and released their own first 8-bit computer, the Atari 800, and its smaller clone, the Atari 400, in 1979, according to PCWorld. It put out several more computers after that, though the one that was supposed to be an upgrade to the 800 was so glitchy that sales of the 800 actually went up. Then everybody wanted a bite of the Macintosh when it released in 1985. Atari's answer was the 520ST, which had a mouse, a floppy disk drive, and an option for a color monitor. Atari PCs were supposed to be a follow-up to the wildly successful 2600 game console, but the computer business just wasn't it for Atari.

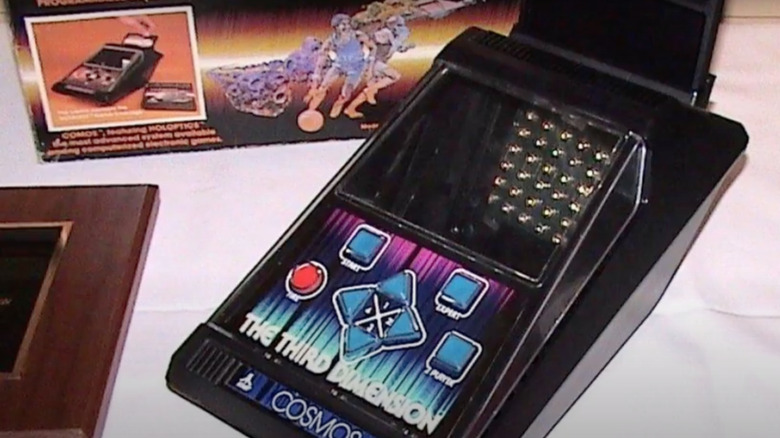

Atari went there and created a holographic game

Atari's Cosmos was way ahead of its time. While other handheld games were still stuck in the pixelated 2D phase, this one went into the realm of holography (sort of).

While it didn't use actual holograms, Cosmos came as close as possible with holographic images that had LEDs moving behind them to bring them to life, according to Atari Historical Society. Atari bought the rights to every bit of holographic technology it could possibly get its hands on. The special effects on other handhelds didn't go beyond flashing LED lights; by using holographic images as backdrops, Atari could create games with 3D environments. Allan Alcorn, Harry Jenkins, and Roger Hector made this genius concept a reality, with Alcorn as the head of production. He remembers meeting with physicists to help him understand the science behind holography.

The problem was that holograms were prohibitively expensive to manufacture. Eventually, one holographer, Steve McGrew, found a solution in Mylar (the same stuff those shiny balloons are made out of). He experimented with it in the lab until he was able to emboss sheets of Mylar with holograms. Alcorn and his team were excited until they ran into the new managers — Nolan Bushnell and Ted Dabney had left Atari by then — who resisted the idea because it was something they had never seen before. They took the prototype to the New York Toy Fair in 1981 but were shut down by management again. Cosmos was never released.

Atari's E.T. game was such a bust it was buried in a junkyard

There was one Atari game that could not live up to the hype no matter how it tried to phone home.

1982's "E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial" video game for the Atari 2600 landed just in time for the holidays. You were supposed to get E.T. home without letting him be captured by curious scientists or the FBI. Earthlings were excited at first, as many admitted in "Atari: Game Over." The game was created by designer Howard Warshaw, who was asked by Steven Spielberg to make something like "Pac-Man" but insisted that the industry needed something new. Gamers were initially excited to get their hands on "E.T.," but they ended up frustrated by the confusing gameplay. "I did the 'E.T.' video game, the game that is widely held to be the worst video game of all time," Warshaw told NPR in 2017.

Sales quickly plummeted, and Atari found itself with millions of surplus copies. As gamers who grew up playing Atari testified in "Atari: Game Over," rumors evolved over the decades, and Atari lore said that there was a massive amount of "E.T." cartridges buried deep underground in a desert junkyard. Some versions of the rumor had them covered in a thick layer of concrete. People traveled to New Mexico from all over the country just to witness the 2014 excavation, and while many "E.T." cartridges were unearthed, so were various other Atari products that were not limited to game cartridges. (One of the first things that surfaced was a joystick.)

Nintendo and Sega nearly ended Atari

The NES (Nintendo Entertainment System) crushed Atari when it came out in 1985. By then, the Atari 2600 was starting to show its age, and it was bound to be devoured by something else. Things might have gone differently if Nintendo and Atari had worked together on U.S. distribution of the NES as they had planned, according to IGN. But since the companies didn't see eye to eye on licensing and Nintendo was already thriving in the Japanese market, Nintendo backed out of the deal. Nintendo's Seal of Quality was another blow to Atari. It set boundaries for developers, as Hackaday reports, including what types of licensing agreements were allowed, while giving customers the quality assurance they wanted.

Nintendo was also coming for Atari's handheld market share with the Game Boy. Atari launched its handheld, the Lynx, just after the Game Boy debuted in 1989, as Paleotronic Magazine reports, but the few months in between made all the difference. Atari was so sure the Lynx would dominate the market that it even ran a magazine ad with the headline "Lynx Eats Boy's Lunch." The Game Boy seemed inferior to the more advanced, full-color Lynx, but Nintendo's system prevailed, according to IGN. The Game Boy was far more affordable than the Lynx, and it came with "Tetris," the hottest new handheld game out that year.

The Lynx's color screen wasn't even relevant anymore after Sega Game Gear caught up in 1991.

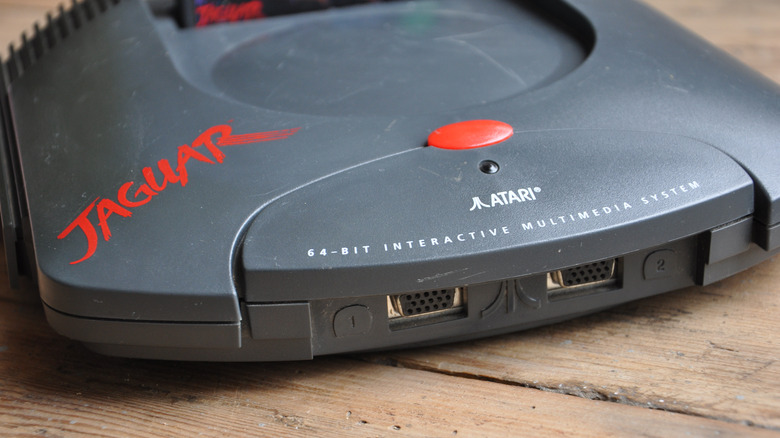

Atari Jaguar was a spectacular fail and the company's dying gasp

Atari released the Jaguar console in 1993 to butt heads with Sega Genesis, Super Nintendo, and the Sony PlayStation. That might have been its worst mistake ever. The Jaguar was supposed to be the console to beat them all. Atari had been secretly developing two new consoles simultaneously — the Panther and the Jaguar — to see which predator would eat the other, according to Atari Age. The Jaguar was a monster 64-bit system compared to the 32-bit Panther. It was a showoff with five processors, super speed, and almost endless data. Evolution won out when the Panther was trashed and Atari started sending out press releases bragging about their killer new machine. It could roar, but could it make it through the brutal video game jungle out there?

What gave the Jaguar more of an edge was that IBM was manufacturing the thing. Atari's marketing plan for it was ambitious, but retailers and the media doubted it would be all that. It was really up to gamers to decide. Whether the Jaguar was a bona fide 64-bit system is up for debate, since some saw it as two 32-bit systems operating together. The visuals weren't anything that 16-bit systems like Super Nintendo and Sega Genesis didn't already have, as SVG says. The games were also not that engaging.

Atari was breathing its last by the mid-'90s, as Atari Age reports. The Jaguar barely made it through 1994 and met its death in 1995. In 1996, Atari called it quits.