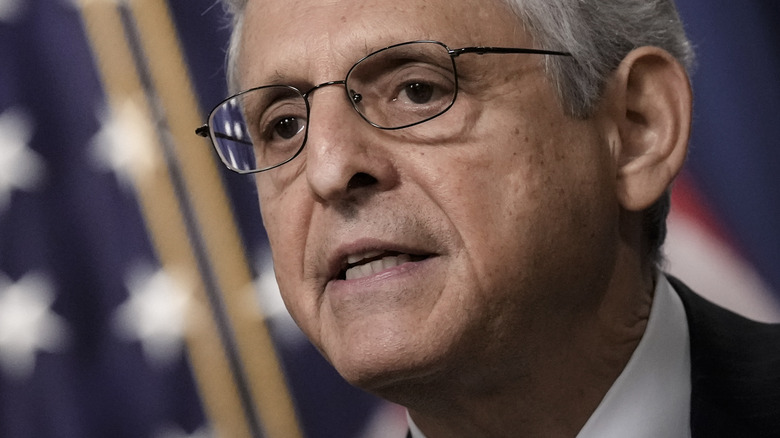

The Untold Truth Of US Attorney General Merrick Garland

It must be a frustrating experience to be denied an appointment one is imminently qualified for due to political maneuvering. According to Politico, Merrick Garland can boast greater experience on the federal bench than any nominee to the Supreme Court in American history. The American Bar Association endorsed him as a well-qualified man of integrity, and when Garland was considered a nominee in 2010, Utah Republican Sen. Orrin Hatch said he could support him as a "consensus candidate" (per Reuters).

By 2016, the GOP's political calculus had shifted. Led by Majority Leader Mitch McConnell, the party put up a united front, refusing to grant Garland even a hearing for consideration. As NPR reported at the time, McConnell's justification was that, in an election year, "the American people should have a say in the court's constitution," despite the absence of any precedent. It was regarded as a ploy to animate conservative voters over the ideological future of the Supreme Court. Garland never became a justice, Republicans won the presidency, and four years later, McConnell reversed himself to confirm Amy Coney Barrett (per Brookings).

Garland may not sit on the Supreme Court today, but his career didn't end with that opportunity in 2016. Before he was a nominee, he was a long-serving member of the DC Circuit Court of Appeals, according to the Department of Justice. And in 2021, he was confirmed by the Senate as attorney general of the United States.

His family fled Russian pogroms

Merrick Garland was born on November 13, 1952. He's a native Chicagoan, growing up in the suburb of Lincolnwood, according to the Chicago Sun-Times. His parents had strong roots in the city from before he was born. His father Cyril ran an advertising firm from home, while his mother Shirley acted as director of volunteer services at the Council for Jewish Elderly. Judaism played a significant role in Garland's upbringing. Per The Forward, he was raised in the Conservative Jewish tradition. His wife Lynn is also Jewish, and while Garland is not currently religiously observant, he retains cultural practices and was married by a Reform rabbi.

Garland, his wife, and his parents are U.S. citizens by birth, but his maternal grandparents came from Russia. Garland himself has spoken of them publicly, in speeches both after his nomination to the Supreme Court and during his confirmation hearings for attorney general (via Jewish Insider). His grandparents lived in the Pale of Settlement under the tsars, right on the border between Russia and the West. Faced with pogroms, the family fled Russia and settled in America.

"I come from a family where my grandparents fled antisemitism and persecution. The [United States] took us in and protected us," Garland told the Senate Judiciary Committee. "I feel an obligation to the country to pay back."

Law was his second choice

Merrick Garland showed an aptitude for the kind of work done by lawyers and judges at a young age. According to The New York Times, he served on the student council and the debate team for Niles West High School. "He understood who he needed to talk to," recalled classmate Donald Silvert. Garland put those skills to the test when he challenged the school dress code. After working with teachers, administrators, and a school psychologist, he won his classmates the right to wear shorts in school.

When Garland went to Harvard, however, law was not his first choice for a career path. According to the Times of Israel, he wanted to be a doctor. He began his pre-med courses, but by his sophomore year, he'd had second thoughts. Law was the field for him after all, it seemed. Garland made the switch and went on to Harvard Law School. He initially entered Harvard on a scholarship, but paying for the law degree required a personal sacrifice on Garland's part: his comic book collection.

As a law student, Garland wrote for the Harvard Crimson and edited articles for the Harvard Law Review. Like many of his peers with high ambitions, he also acted as a clerk for various judges. Among those he worked for was Henry J. Friendly, a New York Court of Appeals judge with a reputation for judicial excellence — and for collecting the best of Harvard's law students.

He has a theatrical side

The legal profession inspires rather cold stereotypes. Lawyers and judges are often portrayed as cerebral, calculating figures. On the other end of the spectrum are the flamboyant showman lawyers, the likes of Johnnie Cochran — and the parodies of such lawyers in shows like "Seinfeld" (via YouTube). Merrick Garland does not have that sort of reputation. On political and ideological matters, he's widely seen as a centrist (per Reuters). A reviewer for the American Bar Association described the legal opinions Garland wrote as a judge as "simple, direct, and [avoiding] unnecessary prolixity."

That doesn't mean Garland doesn't have a theatrical side to his character; it just isn't expressed in the courtroom. As a high school student, per the Chicago Tribune, Garland did some acting, even taking the lead role in a play, and he would maintain his ties to the stage in college. While studying law, Garland contributed to the Harvard Crimson. His writing for the student publication included legal commentary and news articles, but he also submitted his reviews of various theatrical productions. The Crimson has digital archives of his reviews of "The Fantasticks" and three plays penned by Harold Pinter.

Garland still finds outlets for his theatrical interests. In 2020, according to the Shakespeare Theatre Company, he participated in the company's bi-annual Mock Trial event. Garland acted as the head judge, hearing arguments from either side of the "case" of the canceled performance of "Pyramus and Thisbe" from William Shakespeare's "A Midsummer Night's Dream."

He's partially colorblind

Merrick Garland has a reputation for meticulousness. It was one of the selling points used by the Obama administration to try and rally support for Garland's Supreme Court nomination (per an archived page from the Obama White House). The administration referred to Garland's work in carefully reviewing the facts of cases and applying relevant laws, but he extends his fastidiousness into his private life as well. It's through careful attention to detail that Merrick Garland's able to navigate around a minor handicap.

Garland is red-green colorblind, a condition that affects up to 8% of men worldwide, according to Colour Blind Awareness. Besides red and green, people with this form of colorblindness struggle to distinguish certain shades of blue and color combinations that contain some amount of red, like orange, brown, and purple. Red-green colorblindness can be further broken down into two conditions: protanomaly (greater reduced sensitivity to red light) and deuteranomaly (greater reduced sensitivity to green light). Which condition a person has affects which color combinations they have the most difficulty with, though which one Garland suffers from has not been reported.

Colors aren't exactly the first priority for a lawyer or a judge, at least not where their career is concerned. That doesn't mean Garland has no consideration for taste in his wardrobe. To navigate his partial colorblindness, per NPR, he keeps a list to help him tell which ties go with which suits.

He was involved in the Unabomber and McVeigh cases

In 1993, Merrick Garland joined the Department of Justice under the Clinton administration, as deputy assistant attorney general in the criminal division, according to NPR. Within a year, he was the top aide to the department's number two authority, Deputy Attorney General Jamie Gorelick. In that capacity, Garland was put to work supervising investigations into bombings by domestic terrorists. Among the cases under his purview was that of the Unabomber, later proved to be Ted Kaczynski.

Garland also supervised the investigation into the bombing of Oklahoma City in 1995. As reported by The Washington Post, he lobbied for the job, even asking Gorelick to dispatch him to the site after seeing footage of first responders retrieving the dead and wounded from the rubble. Besides supervising the investigation, Garland also assembled the prosecution team that would ultimately try Timothy McVeigh, the domestic terrorist behind the bombing. He successfully lobbied for media access to McVeigh's initial proceeding to counter an anticipated complaint about being denied an open hearing, and he urged his team to demonstrate the integrity and clarity of the American legal system. "Do not bury the crime in the clutter," he cautioned.

Those who worked with Garland on the bombing investigations say that it left a deep mark on him. "He knew and felt the weight of the individual lives lost," his former clerk Clare Huntington told the Post. Garland himself named the investigations as his most consequential work.

The Supreme Court wasn't the first time Republicans held up his career

When Senate Republicans held up Merrick Garland's nomination to the Supreme Court, it was unprecedented in modern American history. Despite Majority Leader Mitch McConnell's attempts to spin a request Democrats once considered sending to President George Bush in the 1990s as such, there was no prior incident around a nomination of that level. But for Garland himself, it wasn't the first time he'd faced political roadblocks on the way to a court seat.

It was 1995, when, according to SCOTUSblog, President Bill Clinton nominated Garland for an open seat on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit. The Republican majority in the Senate gave him a hearing this time, but after asking their questions and receiving Garland's answers, they didn't schedule a vote to confirm him. As NPR notes, the stall on Garland's confirmation lasted 19 months.

The objection from Republicans wasn't over an upcoming election, but about the size of the DC district; they didn't see a need to have a 12th judge on the court. It took Clinton renominating Garland after the 1996 presidential election for Garland to finally be confirmed in a 76-23 vote. Several of the same Republican senators who supported Garland in the '90s lined up behind McConnell's stonewalling his Supreme Court nomination years later (per Politico).

Garland served on the Court of Appeals from 1997 to 2020, becoming the chief judge of the circuit in 2013, according to the Department of Justice.

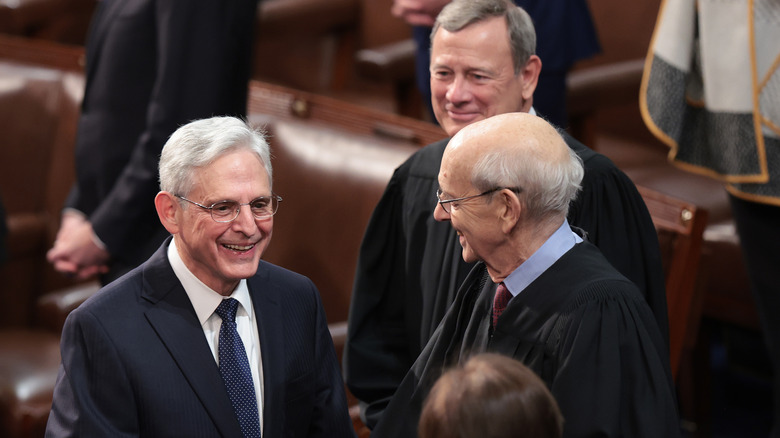

He and John Roberts worked together

Had Merrick Garland been confirmed to the Supreme Court, he would have been reunited with an old colleague. He had been serving on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit for six years when, in 2003, President George W. Bush appointed John Roberts to the court (per USA Today). He and Garland would preside together over numerous cases for the next two years until Bush nominated Roberts for an open Supreme Court seat. By coincidence, according to The New York Times, Garland and Roberts had both clerked for New York's second circuit judge, Henry J. Friendly, though not at the same time.

As reported by USA Today, while working together on the DC circuit, Garland and Roberts were often aligned. In cases of significance, they agreed 85% of the time. There were only five substantive cases where the two men disagreed. The chief issue in those instances was the degree of support for government action and oversight; Garland was more supportive, Roberts more skeptical. Roberts dissented from an otherwise unanimous refusal to consider a San Diego developer's challenge to U.S. Fish and Wildlife regulations. Garland dissented from Roberts' opinion that contractors who gave Amtrak faulty cars weren't in violation of the False Claims Act, a case that was brought up during Roberts' 2005 confirmation hearings.

When Republicans refused to act on Garland's nomination to the Supreme Court, there was a bid to get the court to compel the Senate to consider him (per PBS). Roberts rejected the bid without comment.

He has family in state-level politics

Merrick Garland isn't the only member of his family to work in legal or government matters. According to KETV, he's first cousins with Marty Shukert, onetime chief planner for the city of Omaha, Nebraska. Garland's father and Shukert's mother were brother and sister, and the two boys grew up as close as siblings. Despite living far apart and working in different fields, they remain good friends to this day.

Another cousin held significantly more political power one state over. Per WHO 13, Garland is second cousin to Terry Branstad, who twice served as governor of Iowa. Branstad was in office from 1983 to 1999, according to the National Governors Association, and again from 2011 to 2017. Unlike his relationship with Shukert, Garland never knew Branstad growing up. They met for the first time in 2016, though Branstad had written a letter of support for Garland when he was nominated to the U.S. Court of Appeals in 1995.

Garland's cousins differed in their reactions to his nomination to the Supreme Court. Shukert, who visited Garland only the week before the nomination was announced, called it a "dream-like" experience and was quick to praise his cousin as a moderate and well-qualified choice. Branstad made no mention of Garland's fitness for the job, but deferred to Iowa Sen. Chuck Grassley. As chairman of the Senate Judiciary Committee, Grassley was a key figure in the decision to deny Garland a hearing (per USA Today).

Progressives weren't thrilled about his nomination

When Senate Republicans denied Merrick Garland so much as a hearing, Democrats were united in frustration (per NPR). Six years later, when Donald Trump led a Republican outcry over the FBI's raid of Mar-a-Lago, Democrats put up a similarly united front in defending Garland as attorney general (per ABC News). But before support or opposition to Garland became a political battleground separating red team from blue, he had inspired harsh criticism from members of the progressive left as well as the right.

Garland has long had a reputation as a political centrist. He was sufficiently moderate to attract praise from liberal Democrats and staunch Republicans prior to 2016, and he rarely dissented or inspired dissent from his fellow judges on the U.S. Court of Appeals, according to Bloomberg. Among the issues where Garland was most deferential was campaign finance. As reported by The Hill, Garland signed on to the opinion in SpeechNow.org v. FEC in 2010.

SpeechNow took the Supreme Court's ruling in the Citizens United case and expanded on it, allowing certain types of political action committees (PACs) to accept unlimited contributions. The decision effectively created modern super-PACs and let anyone who wanted to circumvent contribution limits to preferred candidates. Besides concurring with the majority on SpeechNow, Garland also favored law enforcement and the Bush administration's policy toward prisoners held in Guantanamo Bay, giving progressives additional reasons to be disappointed in his nomination (per Reason).

His daughter also missed out on the Supreme Court

As if it wasn't bad enough that Merrick Garland couldn't get a hearing on his Supreme Court nomination, another member of his family missed out on serving the highest court, too. His daughter Jessica lost an opportunity to work for one of the sitting justices in 2020. It wasn't Senate Republicans who cost Jessica the job, however; it was her own dad.

Jessica Garland graduated from Yale Law School in 2019, per Reuters. Like her father before her, she went to work as a law clerk for various judges. She worked under Judge David Barron on the 1st Circuit Court of Appeals and Judge Paul Engelmayer, a district judge in Manhattan. The next step seemed to be a clerkship for the Supreme Court. Justice Elena Kagan hired Jessica in 2020 for the 2022-2023 sittings.

Unfortunately for Jessica, President Joe Biden nominated her father to be attorney general the following year. To avoid any potential conflict of interest, Jessica had to give up a clerkship with Kagan and would have to decline any future offer to work at the Supreme Court until her father leaves his post at the Department of Justice. Reuters did not report any animosity in the family over the way things worked out.