Inside Abraham Lincoln's Plan To Relocate Formerly Enslaved People To Haiti

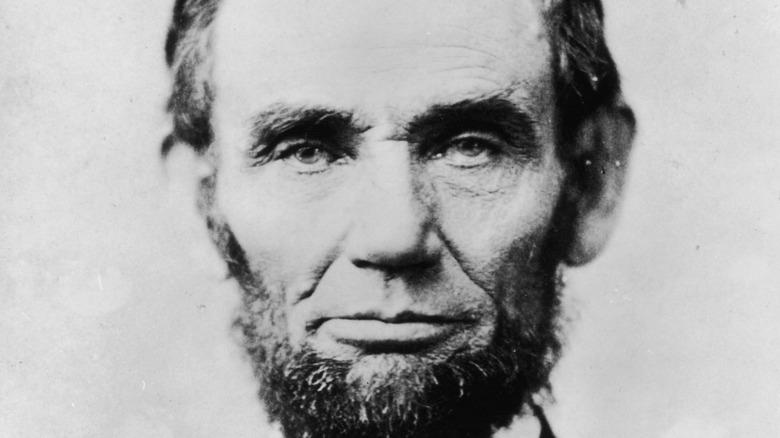

Abraham Lincoln might've issued the Emancipation Proclamation, with famously freed slaves in the south, but this didn't mean that Lincoln was in favor of African Americans integrating into white American society. Lincoln was opposed to racial integration, according to History. Though Lincoln heavily disapproved of the institution of slavery, he didn't believe it would ever be possible to fully integrate Black and white Americans, so as the Civil War was ongoing and he turned the message from preserving the Union to ending slavery, he was articulating new plans to ship the formerly enslaved to establish colonies elsewhere, including Haiti, according to History.

In a eulogy for former secretary of state Henry Clay in 1852, Lincoln said, "If as the friends of colonization hope ... [we] succeed in freeing our land from the dangerous presence of slavery; and, at the same time, in restoring a captive people to their long-lost father-land, it will indeed be a glorious consummation" (via History). Once he was president, he really started to put his plan into action.

Reconciling with a post-slavery nation

Lincoln signed a deal with a Florida cotton plantation owner, Bernard Kock, to use federal funds to send 5,000 formerly enslaved people to Île à Vache (also known as "Cow Island"), off the coast of Haiti, on December 31, 1862, a day before Lincoln would announce the Emancipation Proclamation (via History). The plan started back at the 1862 World's Fair in London when Kock devised a plan to transform Île à Vache into a cotton plantation, according to Insider. The idea was that when the former enslaved people were sent to Île à Vache, they would be provided housing and access to schools and hospitals, and required to work on a cotton plantation for four years, then later their wages would be reinstated and they would be allotted 16 acres of land (via History).

This wasn't the first time Lincoln advocated for the colonization of African Americans outside of the United States; he once gave a speech to Congress advocating for a constitutional amendment that would approve colonization, according to History. However, even when Kock's plan was approved by Lincoln, it wasn't mandatory for the former slaves, but it was highly encouraged by both Lincoln and Kock, along with others (via History).

African Americans and abolitionists strongly opposed Lincoln's plan

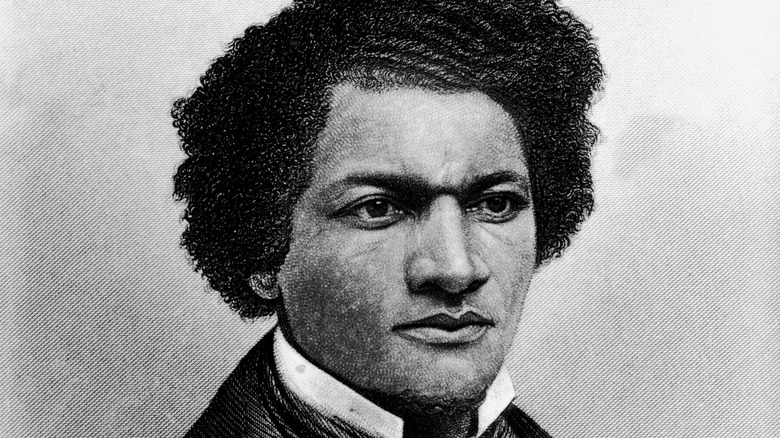

Abraham Lincoln tried to convince abolitionists and African Americans to agree with his vision of colonization, but his opinions were highly opposed by these groups. In 1862, Lincoln held a meeting with a delegation of African American leaders to discuss the integration between white and Black Americans. Lincoln told them, "Your race suffer from living among us, while ours suffer from your presence ... It is better for us both, therefore, to be separated" (per History). Frederick Douglass (above), one of the nation's most well-known Black abolitionists, was not at the meeting, but he later commented on it, saying that the proposal "reminds one of the politeness with which a man might try to bow out of his house some troublesome creditor or the witness of some old guilt" (via History).

Kock also did his best to convince African Americans to voluntarily support colonization, writing, "The intelligent negro may enter upon a life of freedom and independence, conscious that he has earned the means of livelihood ... and at the same time disciplined himself to the duties, the pleasures and wants of free labor" (via History).

The colony became a disaster

After Lincoln approved Kock's idea for establishing a settlement on Île à Vache and allocating $600,000 for the effort, an investigation into Kock made Lincoln suspicious. Kock had been wrapped up in shady business dealings before the proposal, and the U.S. Commissioner in Haiti reported to Lincoln that Kock had made no infrastructure for the settlement. In April of 1863 Lincoln went back on the deal, but 453 formerly enslaved people were already on their way to the island, according to Insider.

The colony was considered a failure almost from the very beginning. Some 30 would-be colonists died from smallpox during the sea voyage (via History). When they finally set foot on the island, they discovered that there were no hospitals, and the houses were in fact huts where they had to sleep on the ground. Kock, who managed the settlement, only paid the colonists in fake currency to buy goods at the local store, which Kock owned. On top of that, a second ship that was meant to bring supplies for the colonists never came, which hindered the colonists' quality of life (via History).

Lincoln learns from his mistakes

Eventually, the African Americans living on the island grew tired of Kock's cruelty, and they attempted to overthrow him, according to Insider. Kock fled, and after Lincoln heard about the atrocities being committed on the island, he spoke with chaplain John Eaton, saying that the colonists "in the Cow Island settlement on the coast of Hayti were suffering intensely from a pest of 'jiggers' from which there seemed to be no escape or protection" (via History). He later sent a navy vessel to rescue the remaining survivors, according to Insider.

After this failed experiment, Lincoln never supported another colonization effort. John Hay, Lincoln's personal secretary, wrote in his diary, "I am glad the President has sloughed off that idea of colonization. I have always thought it a hideous & barbarous humbug" (via Insider). Though this part of Lincoln's legacy is not well-known by the American public, examining his complicated attempts to deal with a post-slavery society in the United States is a reminder of how difficult the post-war Reconstruction era was for African Americans, and the nation as a whole.