What Did Ancient Mesopotamians Believe About Ghosts?

We can't really escape ghosts. Sure, you may be skeptical in the extreme, but there is a good chance that an odd shadow or tale told around the campfire has raised the hairs on your arm. Don't feel bad, though. It's a natural reaction, even if it pushes the boundaries of belief for many. As American Scientist argues, it may even be a symptom of a cognitive trait that gave early humans an evolutionary advantage over other creatures.

This sort of belief has a real pedigree, too. While you may be used to modern horror movies and creepypastas that deal in ghosts, those are only the latest in a very, very long line of spooky tales. How long? Just ask the ancient Mesopotamians. More than 5,000 years ago, people in this region — which encompasses the cultures of Babylon, Sumer, Akkad, and Assyria — were already living in complex, urban settlements in what's now Iraq and Syria (via the University of Cambridge). What's more, they were a literate people who wrote down all sorts of things, from accounting records to folklore. To do that, scribes grabbed a clay tablet and a stylus and began writing in cuneiform, one of the earliest known writing systems.

Inscribed on some of those ancient clay tablets are tales of ghosts. The spirits of dead folks were apparently quite the force in Mesopotamia, demanding tribute and sometimes causing ill-fortune and poor health, per the World History Encyclopedia. Here's what the ancient Mesopotamians believed about ghosts.

Ghosts were a fact of daily life in ancient Mesopotamia

For the ancient people of Mesopotamia, the returned spirits of the dead weren't occasional visitors. Instead, they made regular appearances, even if they often went unseen — though not undetected. For some Mesopotamians, ghosts were as much a part of the natural world as anything else, as real as the earth beneath their feet or the sky above their heads.

In part, that was because the dead were very close to the living. According to "The First Ghosts," separate cemeteries for the dead were actually the exception to the Mesopotamian rule. Instead, it was more likely that one's deceased relatives were buried nearby, or even within the house itself. If someone was being afflicted by a ghost or otherwise had an encounter with a human spirit, then chances were pretty good that it was one of the family members lying just beneath their feet.

This proximity also meant that ghosts made up a family's daily chores. Alongside mundane activities like preparing food and keeping the home clean, someone would also be tasked with taking care of the lingering dead. According to British Museum curator Irving Finkel, interviewed by History Extra, it was typically the oldest son who would go out into the courtyard (the usual burial spot) and make offerings to the dead there. If he failed to do so, the deceased family members would be wanting in the afterlife and might just return as angry ghosts to wreak havoc within the household.

Ghosts were assumed to be stuck in the past

As in many other cultures, it seems that the Mesopotamian dead were assumed to have been somewhat frozen at the time of their death. According to the Hebrew Union College Annual, one of the most common offerings to the dead of Mesopotamia was roasted grain or beer made from more of that prepared grain. It's not just that someone's spirit might have thought this was tasty, or that it was an easy meal to prepare for someone who, at least in the real world, was never going to eat it. Roasted grain may well have been offered because it was an ancient sort of meal. Even thousands of years ago, this was considered to be a seriously vintage way of getting in a good snack. For the Mesopotamians who were just trying to appease the shades of long-gone relatives, an old-school meal served up to the ancestral spirits may have seemed especially fitting.

A few Mesopotamians tried to speak to ghosts in archaic languages (via Hebrew Union College Annual), not unlike horror movies that have priests communicating with ghosts in Latin. It may have been difficult to do this well, just as you might have a tough time shouting "the power of Christ compels you" in Aramaic on short notice. So, some people fudged the rules. An ancient prescription against ear troubles recommends contacting the ghosts causing the problem in an ancient but very garbled version of other people's languages.

Normal ghosts may have been sleeping

Under normal circumstances, a ghost that was given the proper offerings would mind its own business. It would have to behave itself, given that the normal state of departed spirits was to remain in a kind of suspended animation where bugging the living simply wasn't a possibility. According to the Hebrew Union College Annual, ghosts tended to fall into a quasi-sleep if they were properly buried. If a spirit's family did their duty and supplied their dead ancestors with the right sort of offerings on the correct schedule, then the ghosts would keep on snoozing. A few texts and inscriptions certainly present this picture, referencing souls resting or sleeping after they depart the earthly realm. Even Gilgamesh, the famous hero of Babylon, compares the dead and sleeping, but alive humans.

The association between sleep and death was so strong that ghosts were referenced in spells meant to help people get some rest (via Hebrew Union College Annual). Fussy infants might be commanded to sleep "like a dead person," who surely wouldn't be flopping around and crying in their resting place. So, too, might an insomniac Mesopotamian draw on a spell that would hopefully let them achieve a deep, restful sleep free of tossing and turning. Similar spells were used to quell demons and take the energy away from an assailant, associating them with a horde of sleepy and nearly powerful ghosts.

The Mesopotamian underworld was a bummer

Per the World History Encyclopedia, all deceased Mesopotamians would find themselves in an exceedingly gloomy realm, called Irkalla or "the land of no return." There, sustenance was to be found in dust and muddy puddles. No wonder some spirits tried to make a run for it back to the world of the living, though they risked serious consequences if caught. If apprehended, a runaway ghost could be punished by the sun god Shamash, who would confiscate that ghost's offerings and hand them out to spirits of forgotten people.

With a fairly diverse culture, this wasn't the only Mesopotamian take on the underworld, though all had the same lack of cheer. In "Gilgamesh, Enkidu, and the nether world," the king Gilgamesh is given a drum and drumsticks (ellag and ekidma), which both manage to tumble down to the underworld. His best friend, the wild man Enkidu, offers to retrieve the instruments. Gilgamesh warns him not to bring attention to himself on this perilous quest, but Enkidu does just the opposite and is trapped in the underworld. Gilgamesh at least is able to meet with Enkidu's ghost, who proceeds to tell him that most people in the world of the dead are in pain or languishing forgotten. The stillborn children, however, have a better fate. According to Enkidu's spirit, they "play at a table of gold and silver, laden with honey and ghee," enjoying an afterlife far better than the human life they never had.

Unhappy ghosts came back

Though the dead were supposed to be sleeping or hanging around the gloomy underworld, minding their own business on their side of existence, a bump in the road could mess everything up. That's because any number of things could make a dead person come back as a ghost. A spirit was probably making themself known because one of two things had happened: their rights had been impugned, or there was something off about how they had been buried or died (via "The First Ghosts"). Thus disturbed, they could wreak havoc in the world.

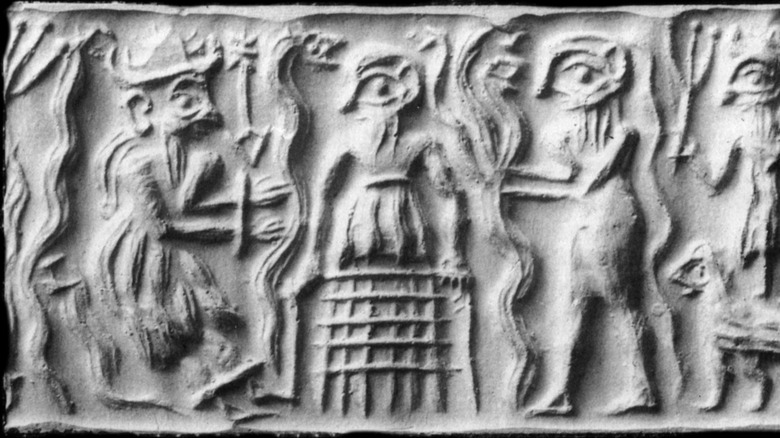

According to the World History Encyclopedia, ghosts would essentially get a special pass to visit the land of the living courtesy of Ereshkigal, the Queen of the Dead who ruled over their gloomy afterlife. The aspect of a person that survived death and could travel back to communicate with or bother the living was known as the gidim. Generally speaking, it was Ereshkigal's job to keep the dead and living separate, though exceptions could be made when justice had been upended. On other occasions, a particularly determined gidim might escape the watch of the queen, though they were often eventually caught and returned to their rightful place with the other dead people. A mortal or a divine being like Ereshkigal's younger sister, Inanna, might also break their way into the underworld, though it was a journey that demanded much even of the gods, much less pitiful human spirits (via World History Encyclopedia).

Medical issues could be caused by a spirit

If a ghost did get a pass to visit the living or at least snuck its way past the gate, then how would the living know it was around? For many people throughout Mesopotamia, a sure sign of a ghost was an illness, per the World History Encyclopedia. As if being sick weren't bad enough, most interpreted the illness as a manifestation of that person's wrongdoing. A ghost or other spirit was offended by that living person's misstep, intentional or otherwise, and was punishing them through physical affliction.

Though a ghost might have caused a sickness, other spirits could be called in to help, too. According to "The First Ghosts," family ancestors could be called on to help in these sorts of situations. If they had been given the right sort of attention, namely through regular offerings meant to appease them and make their afterlife more comfortable, then they might be inclined to help an ill family member on the spiritual plane.

Religious authorities might be called on to fend off ghosts

Sometimes, the presence of a ghost was such an issue that professional help had to be called in. For people throughout ancient Mesopotamia, that could mean a religious figure like a priest or diviner. According to "The First Ghosts," that exorcist would have a fair amount of work ahead of them, as their magical litany involved going down a sometimes extensive list of potential spirits who could be bothering a person. Was it someone who had drowned? Someone who died of the cold? Fire? Was the ghost remembered or forgotten? Heck, it might even be a non-human entity like a demon, so many incantations threw their names in for good measure.

Properly identifying a troublesome soul would hopefully give the exorcist enough power over a spirit to banish it, but that wasn't the only part of the ritual meant to deal with ghost troubles. As the World History Encyclopedia notes, the pressure wasn't all on the ghost. The exorcist also had to interrogate the sick person, rooting out any sins the individual might have committed that would have angered a spirit.

However, as "The First Ghosts" author and curator Irving Finkel told History Extra, just because priests sometimes got involved in exorcisms didn't mean banishing ghosts was exactly an official part of Mesopotamian religion. Even so, they might call upon the gods themselves to handle an especially recalcitrant ghost.

Ancient Mesopotamian cuneiform tablets are inscribed with ghost busting spells

Magical incantations were key to many a Mesopotamian ghost banishing, per History Extra. Some were quite simple, while others could take up a lot of time and mental power to finally get rid of a troublesome ghost. They could also run up a serious bill, with potentially expensive ingredients and extra portions of beer required for success. We know of these because they were inscribed on clay tablets in cuneiform, the wedge-shaped writing system employed by literate Mesopotamians.

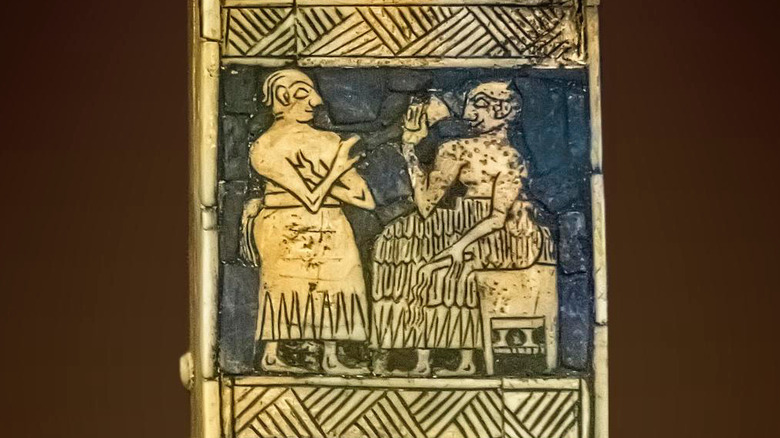

One particular tablet offers up what may be the very oldest depiction of a ghost ever. According to The Guardian, it was uncovered by none other than British Museum curator and scholar of Mesopotamian ghosts, Irving Finkel. Though the tablet had been incorrectly assumed to be blank, looking at it from the right angle and with the correct lighting shows a male ghost with his hands bound, being led away by a woman. The implication was that the ghost needed a girlfriend to pull him away from the living and back into the underworld.

Besides the illustration, the tablet is also inscribed with an anti-ghost set of instructions. Though the spell is fragmentary, it includes directives to make two small figures and dress them in specific tiny clothing, burn juniper, and bring along two containers of beer. Perhaps most important of all — or at least, in a very creepy turn — the spell warns the reader not to look behind them.

Ghosts might have helped ancient Mesopotamians tell the future

Though many people seem to have either wanted to keep ghosts happy or simply make the more troublesome ones go away, other people in ancient Mesopotamia purposefully called up the dead. Given their links to the supernatural, unseen world, ghosts could prove to be pretty useful to the living. That is, so long as the alive person who drew upon them knew what they were doing.

This practice of communing with the dead to get a leg up in the world, known as necromancy, was already established practice for the ancients. Mesopotamians believed that it was possible and even useful to call up the dead, though Archiv für Orientforschung notes that we can't be sure if this was a regular feature of Mesopotamian life or if necromancy only happened on rare occasions. It features in the tale of Gilgamesh, who is able to speak with his departed friend Enkidu after the latter's spirit is drawn up from the underworld through a necromantic ritual.

Speaking with the dead could put you in a vulnerable position, so it was critical to follow the procedure closely. One cuneiform tablet in the collection of the British Museum lays one such spell out, including instructions for a special eye ointment and tips for avoiding danger. Perhaps because it seems to have been such a perilous venture, references to necromancy are hard to find from the time period.

Becoming a ghost could be a punishment

If the best a ghost could hope for was a sleepy afterlife, then a restless one was torturous. That might happen because they were forgotten or they had a neglectful family who hadn't prepared the correct offerings for their ancestors. Going through the roll call of ghosts often employed by Mesopotamian exorcists, it seems like any number of chaotic or careless accidents might make a ghost.

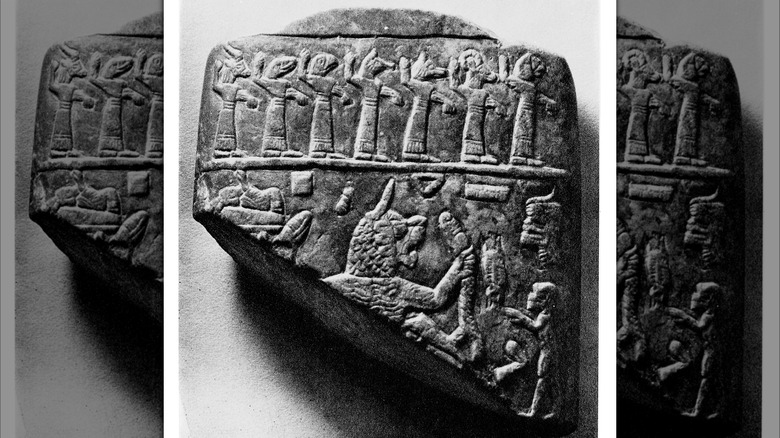

But sometimes, it wasn't an accident. A ghost might become a wandering spirit as part of an act of revenge. That was part of the tactics used by Assyrian warrior king Ashurbanipal. According to The British Museum, he reigned over what was then the largest empire in the world, around 669-631 BCE. Though his subjects apparently respected their king, the enemies of Ashurbanipal were faced with his fearsome side. His brother, the lesser king of Babylon, became troublesome and reportedly met his end inside a burning palace, courtesy of Ashurbanipal's forces.

The emperor's enemies might fear him even after his death. In one instance, Ashurbanipal crushed the rebellious people of Elam and carried their king's head back to the capital of Nineveh to display it there. He also ransacked the ancestral tombs of the Elamites, scattering the bones inside and proclaiming that he had denied their ghosts the all-important offerings and rest that was their due. Given that he recorded his boasts for posterity, Ashurbanipal apparently wasn't worried about ghosts coming back to hound him.