Animals That Would Have Gone Extinct Without Zoos

Zoos get a bad rap sometimes. On the surface, they can seem pretty cruel. Here you have all these wild animals, meant to be out there in the open with no fences or barriers to hold them in and no tourists gawking at every little thing they do. The Humane Society has some scathing opinions of zoos in general, mostly focused on non-accredited zoos, and how they cage wild animals. When you look at it like that, zoos are pretty awful, and animals would be better off without them, right?

Maybe. But there are two sides to this token, and the other side is that zoos do a lot of work toward the conservation of dying species. Too many have gone extinct already. We will never see dodo birds in real life, and that's nothing short of tragic — they look like they'd be a lot of fun. Without zoos, many more animals would have joined the extinct list from habitat loss, climate change, and other factors.

Of course there are bad zoos out there, but the ones that work toward conservation deserve plaudits for their tireless efforts to keep species alive. Here's a look at some of the invaluable species that have only survived this far because of the intervention of zoos.

Przewalski's horse

Wild horses used to be a much bigger thing than they are today. There were horses all over the place, but as a result of domestication and habitat loss, the numbers have steadily dwindled over the years. Nowhere has that been more apparent than in Mongolia, the birthplace of the greatest horse lords in history, the horde of Genghis Khan. But long before the Mongols rose to power, the Przewalski's horse population roamed freely. They were first documented scientifically in 1881, according the San Diego Zoo.

By the 1960s, it looked like there would be no saving the wild population. Due to domestication, severe weather, disease, and wolves, the wild horse numbers were dwindling. This is when the San Diego Zoo, among others, stepped in to try to reverse that downward trend. While it didn't prevent an extinction in the wild, the domestic efforts to preserve the species were underway.

In 1969, the San Diego Zoo had their first Przewalski's horse birth, which in turn gave way to a herd at their Safari Park. Nowadays, zoos around the globe are working to build a sustainable Przewalski's horse wild population. More than 157 horses have been born at the San Diego Zoo alone, and the species has been reintroduced to Mongolia, China, and Kazakhstan.

Golden lion tamarin

The very idea that these cute little golden goblins could go extinct is intolerable. Thankfully, the intervention of zoos has us past the point of having to worry about it. It all began where so many other near-extinctions began: in the heavily deforested areas of South America, particularly in Brazil. With the destruction of natural habitats in the Brazilian rainforests, the golden lion tamarin was reduced to 2% of it's usual range, according to Save the Golden Lion Tamarin, a nonprofit whose name says it all.

In the 1960s, it was estimated that only 200 wild golden lion tamarins remained. Over the course of two decades, the zoo population of the adorable little monkeys grew to 500, which opened the door for 146 to be released into the wild over a 15-year stretch leading into the 2000s. That number grew into the thousands, though the problems facing the species persist. Deforestation has carved their once-expansive natural habitat into scattered parcels of rainforest that are too small to support a thriving population.

Deforestation isn't the only issue, though. In 2018, a yellow fever epidemic saw the population of 3,600 wild golden lion tamarins reduced to only 2,500. Today, the tamarins have been vaccinated for yellow fever, and efforts are underway to regrow the rainforest. It looks like the path might be clearing for arguably the most adorable little primate in the world.

Amur leopard

One of the most critically endangered species on this list, the Amur leopard population recently dipped to only around 30 individuals in the wild, with extinction just around the corner (per the Audubon Nature Institute). In response, the effort to save the Amur leopard became a massive undertaking across numerous organizations around the globe, and by all accounts, it's working. With a coat that is ripe for poachers, it's a sought-after target, but that isn't the only threat the leopards face. Habitat loss, inbreeding from a dwindling population, and having to share territory with tigers all work to hinder the recovery of this beautiful big cat species.

It's not all doom and gloom, though. There are so many zoos and preservation societies working to reestablish the wild Amur leopard population that it seems almost inevitable that it won't right what was a sinking ship. And thanks to the Global Species Management Plan, talks are ongoing between nations that aren't always on the same political footing, such as China, Russia, and the United States, all banding together to protect a dying cat.

The Memphis Zoo is one of the zoos leading the charge on the Amur leopard front, both with fundraising and by housing their own Amur leopard, named Sputnik. By their estimation, because of worldwide efforts across zoos and beyond, the Amur leopard's wild population has risen by several dozen members over the past decade, placing an estimate of 120 in the wild.

Peregrine falcon

The peregrine falcon is the fastest animal on the planet, able to reach speeds up to 200 miles per hour when diving after prey (per the Los Angeles Zoo). With that kind of ability, it's hard to imagine the species facing any serious threat to longevity. Then there's the matter of how widespread they are — these raptors are found on every singly continent except Antarctica. So how exactly does a predator that capable and that widespread end up nearly extinct on an entire continent? In a word, humanity. More specifically, North American humanity.

While the peregrine falcon wasn't necessarily at risk of worldwide extinction, the risk of local extinction, or extirpation, was incredibly high and almost realized. According to The Nature Conservancy, it all began with pesticides, particularly DDT. These pesticides were sprayed all over North American farmlands and absorbed by peregrine falcon prey, which ended up in the falcons themselves. The result was a degradation of the falcons' eggs, which lost their integrity and prevented chicks from hatching successfully. Just like that, one pesticide almost took out an entire species on a single continent.

That's when zoos stepped in. Per the Los Angeles Zoo, since a breeding program was introduced in 1972, some 6,000 peregrine falcons have been released into the wilds of North America, removing them from any concern and making them one of the most resounding zoo conservation success stories.

Sea otter

We'd all rather not find out how the world would cope without sea otters. And unfortunately, sea otters still rank as endangered, though the efforts to preserve them are seeing immense success. And it's not just about preserving the species; it's also about the critical role they play in the environment. According to Monterey Bay Aquarium, sea otters keep kelp forests alive and healthy by eating urchins, and they help eelgrass thrive in estuaries by eating crabs. Remove them from the ecosystem, and you're not just losing the cute and cuddly face, even though that loss is big enough.

The range of sea otters used to be much bigger than it is today. They used to roam all along the West Coast of the United States, as well as in Russia and Japan, but in the 18th and 19th centuries, otters were so widely hunted that they were thought to be extinct by the 1920s. But then 50 seemingly appeared out of nowhere near Big Sur. Those 50 became the starting point for the sea otter conservation movement.

One of the leading efforts on that front comes from the Monterey Bay Aquarium, which hosts five surrogate mother otters who train orphan sea otter pups before they can be released into the wild. This aquarium alone has released 37 otters, though the key is expanding the wild range of the species, since California can't support any more. And that's where the story leaves off for now, with about 3,000 wild California sea otters looking for more range.

California condor

The California condor is the largest land bird in North America, with a wingspan capping out and 9 and a half feet, according to the Santa Barbara Zoo. However, that wingspan isn't always a blessing. It has lead to numerous electrocution deaths, which is just one threat on an expansive list that includes lead poisoning, car collisions, trash consumption, and more. As the National Park Service points out, all of these threats are thanks to humanity.

Many of the animals on this list were singled out by the Endangered Species Act of 1967, an act designed to help restore numerous species to the wild. The California condor was one of the first animals protected under that act. When 1987 rolled around, these massive birds only numbered 22 in the wild, and that's when zoos stepped in. The 22 survivors were rounded up, and a conservation program was put into place to prevent them disappearing forever.

The Santa Barbara Zoo is one of several partners involved in the decades-long conservation program that saw those last 22 condors become the start of a new population, which now numbers in the 200s, according to CNN. They have begun to reappear in the redwood forests of California, where they had previously been erased, and while only 93 of those 200 birds have offspring, the efforts to rebuild the population are ongoing.

Black-footed ferret

Black-footed ferrets, which are just as adorable as the ferrets you can get as pets, used to roam the plains of America, preying on the native prairie dog population and thriving. Any time humanity enters the equation, however, things tend to take a turn for the worst. All signs pointed to the ferrets going extinct due to habitat loss, humanity's natural spread, plague, and a decrease in the prairie dog population (according to Defenders of Wildlife). But a small population of black-footed ferrets was found in 1981, according to Smithsonian's National Zoo and Conservation Biology Institute, and zoos around America wasted no time getting a plan in place.

By 1988, reintroduction had already begun, and efforts to rebuild the population were well underway at the Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute (SCBI) in Front Royal, Virginia. Thanks to this facility alone, 1,029 black-footed ferrets have been reintroduced across the American West and beyond, with there now being 28 reintroduction sites spread around Wyoming, South Dakota, Montana, Arizona, Colorado, Utah, Kansas, New Mexico, Canada, and Mexico. Some 139 of those reintroduced animals were from artificial insemination. Outside of the SCBI, six zoos are responsible for the births of over 7,000 black-footed ferrets, 2,600 of which have been reintroduced into their natural habitat.

According to the Smithsonian, every single year, as many as 220 black-footed ferrets are released into the wild. Sadly, threats still exist, and the wild population still struggles to sustain more than a few hundred individuals, according to The Nature Conservancy.

American red wolf

The American red wolf was declared extinct in the wild in 1980, according to the Center for Biological Diversity. This is another species that used to have a huge range, stretching from the Gulf of Mexico on up to Pennsylvania and out into the central plains of the Ohio River Valley. That's a lot of ground, but it's also prime human expansion territory, and that's what led to the decline of the wolves. Due to habitat loss, illegal killings, and cross-breeding with coyotes, the American red wolf looked like it was done for.

Starting with a population of just 14 wolves, the Species Survival Program kicked in and began to rebuild the wild population of wolves, according the Red Wolf Coalition. Of course, in order for that to work, you need a lot of facilities on board to breed the wolves and reintroduce them to the wild. The Species Survival Program counts 44 different facilities helping the red wolf survive, including a whole slew of zoos from Rhode Island to Washington state.

The Red Wolf Recovery Program reports that numerous red wolves have been released into the wild, with the population fluctuating as low as seven and as high as 120. But in captivity, there are around 243 wolves being nurtured to keep the species alive. Now it's just a matter of getting their natural range clean and clear enough to sustain them for the long haul.

Arabian oryx

The thing with beautiful animals is that they will seemingly always be hunted for whatever makes them beautiful. For a lot of animals, that's a gorgeous coat, spotted, striped, or what have you. For other animals, it's their horns, and that's what the Arabian oryx has: beautiful, spiral horns that many believe to have magical qualities. This has caused it to be hunted since long, long before the modern period, but according to the Phoenix Zoo, because of motorized vehicles and automatic weapons, the mass slaughter of this species escalated so much that the Arabian oryx went extinct in the wild in 1972.

Thanks to leaders like the Phoenix Zoo, that has not been a death sentence for the species as a whole. In 1962, a team went into the Arabian Desert and captured two males and a female oryx with the intention of preserving this species in the wild. Those three oryx, along with six specimen donated from other zoos and private collections, made the long trek back to Phoenix and began creating what would become the repopulation of the Arabian oryx in the wild.

And it's a good thing they did, because 10 years later, they went extinct in the wild. Ten years after that extinction and 20 after the program began, the Arabian oryx was reintroduced to the wild thanks to a coalition involving six world governments, five zoos (including the Phoenix Zoo), and numerous societies, conservation programs, and nonprofits. Today, there are 1,220 Arabian oryxes in the wild, with another 6,000-7,000 in semi-captivity, according to Arab News.

Panamanian golden frog

These tiny, vibrant frogs may look hard to miss, but it's quite possible they are, at this very moment, extinct in the wild, according to the Maryland Zoo. This is another creature that might seem like an unlikely candidate for extinction. Given how small they are, the fact that they lay 200-600 eggs at a time, and, of course, the little factor that they are deadly poisonous, they seem like a hard species to completely wipe out. But amphibians as a whole are dying out incredibly quickly, with about 2,000 of the 6,000 known species at risk of extinction. It has come to be known as the Global Amphibian Crisis, with the primary threat being habitat loss.

But the Panamanian golden frog has a great ally in the Maryland Zoo, which is leading the effort to save these little golden fellas. While they have not been seen in the wild since 2009 (per The Guardian), the Maryland Zoo is the first place to successfully breed the frogs in captivity, giving new hope to a species that teeters on the brink of extinction every single day.

While the efforts are ongoing and major breakthroughs are still waiting, the frog lives on as long as it has the Maryland Zoo in its corner.

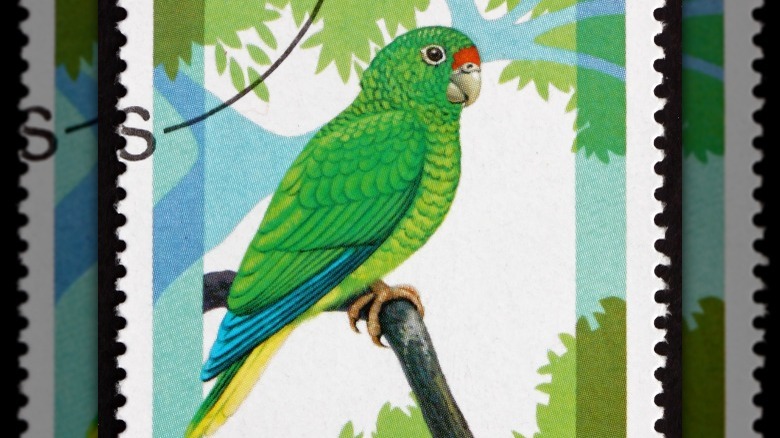

Puerto Rican parrot

It's a vital step in any critically endangered species recovery program to get a zoo in its corner, leading the charge for preservation. For the Puerto Rican parrot, that zoo is the Lincoln Park Zoo. In 1975, the Puerto Rican parrot wild population had dwindled down to just 13 members due to the far-too-prevalent scourge of habitat loss, as well as hurricanes and predation.

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and Puerto Rico Department of Natural and Environmental Resources stepped in during the '70s, and a captive breeding program began in collaboration with zoos and their scientists and biologists. The Lincoln Park Zoo is one of the leading organizations in monitoring and protecting the growth of the Puerto Rican parrot as its wild population continues to expand. Now, there is confidence that the recovery will be a successful one. According to the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation, the wild population had grown to 77 as of 2018, with another 463 in captivity, hopefully ensuring a prolonged, sustainable release program.