Things We Believed During The Cold War That Ended Up Being Wrong

Truth is the first casualty of war, and that's the case even when the war in question is chilled to the point of absolute zero. The Cold War was a half-century wang-measuring contest that, like most wang-measuring contests, threatened to spill over into violence if either participant felt their manhood was coming up short. Except the wangs in question were substantial nuclear arsenals, and the participants had a resource typically not available to bros in locker room contests: a well-oiled propaganda machine.

From a young age, kids growing up on the side of NATO and capitalism were taught to believe a whole lotta things about Russians, Communism, and the USSR, none of them particularly complimentary. While some later turned out to be truer than anyone could have imagined — say hello to the reality of life in the gulags — some of it was almost on par with believing that the Moon is made of сыр. (That's Russian for "cheese," kids!) Here are some common misconceptions about the Cold War.

The Red Scare was purely a witch hunt

He may not have been hauling around a leather-bound Bible and a set of thumbscrews, but Senator Joseph McCarthy was still America's witchfinder general. During the postwar Red Scare, he and FBI Director Edgar J. Hoover conspired to root out all Communist influences in American life. In practice, this meant creating what History Channel called a "climate of fear and repression" where anyone could lose their jobs over the merest rumor of Commie sympathies.

Even as it was happening, the Red Scare was condemned as a witch hunt. Arthur Miller's 1953 play The Crucible literally compared the McCarthy hearings to Puritans burning falsely accused witches (according to the author himself). By the time things petered out, the Red Scare was already viewed as an embarrassment.

That all changed at the end of the Cold War. In the early 1990s, top-secret Soviet-era KGB files were briefly declassified. They confirmed that over 300 Communist spies had indeed been active in the USA, working for the government and even on the Manhattan Project. Wrongheaded as their approach was, McCarthy and Hoover really had been onto something.

Oxford Research Encyclopedias has the whole, fascinating story. Unlike a Puritan witch hunt, which obviously wouldn't have featured any actual witches, the Red Scare really did feature a cast of Communists hoping to undermine the United States. Yet there's also no doubt McCarthy's tactics were heavy-handed. Over 9,000 government workers were investigated, 30 times the number of actual Communists in the government.

People hated living under Communism

What comes to mind when you hear the phrase "life under Communism"? The answer probably involves stuff like "the secret police," and "gulags." Films like The Lives of Others have made clear that living in a Communist dictatorship was even less fun than it sounds — and it already sounds less fun than sharing a naked hot tub with your local biker gang — but the reality is more nuanced. In parts of Eastern Europe, life under socialism is still regarded with nostalgia.

There's a German name for the phenomenon: ostalgie. In 2014, Germany's international public broadcaster, Deutsche Welle, reported that nostalgia for life in socialist Germany (the German Democratic Republic or GDR) had created a booming market for old East German products. While no one wanted a return to the days of dictatorship, many spoke about how they missed certain items or ways of doing things. A 2009 poll reported in Der Spiegel went even further, with 57 percent of former GDR residents showing willingness to defend the socialist state.

A Pew Global survey from 2009 was similarly eye-popping. When residents of Eastern Europe were asked if people were worse off now than under Communism, only residents of Poland and the Czech Republic had pluralities preferring post-Communist life. Many saw no difference, while big majorities in Bulgaria, Ukraine, and Hungary thought life had been better in Socialist times. Gee, it's almost like history is less black-and-white than TV would have you believe.

Ethel Rosenberg was definitely guilty

You'd think Ethel Rosenberg's guilt was a settled matter. In 1951, she and her husband, Julius, were convicted of stealing atomic secrets and passing them to the Soviet Union. Two years later, they were executed in the electric chair. While international organizations called them the victims of a witch hunt, most Americans stood by their sentence (via History Channel).

In 2014, the narrative of Ethel's guilt got a nasty shock. Following a close-to-deathbed confession from her brother, David Greenglass, it began to look like Ethel may have been less "guilty" and more "framed."

The Guardian has the details. In 1950, David was called to testify before a grand jury against the Rosenbergs. This was a different hearing than the 1951 trial that would result in Ethel's death sentence, but you wouldn't expect David's testimony to be substantially different. Yet different it was. In 1950, David repeatedly told those present that he had no knowledge of Ethel's involvement with Julius's spying. In 1951, he claimed to have seen her typing out notes to send to Moscow, an explosive claim that helped book Ethel a front row seat for her own execution. What changed between 1950 and 1951?

David may have realized he preferred sex to sisterly affection. The Guardian article theorizes David's wife, Ruth, really played the typist role that Ethel was convicted for. It also implies David may have thrown Ethel under the bus to save his wife. Worst brother ever, or best husband? Discuss.

Yugoslavia was a major success story

They say hindsight is 20/20, and nowhere is that more uncomfortably true than regarding Yugoslavia. The nation (the six countries of Croatia, Bosnia, Serbia, Slovenia, Macedonia, Montenegro, plus the region of Kosovo) was seen in the Cold War as one of the few Communist success stories. Under Marshall Tito, Belgrade stood up to Stalin, kept open borders that allowed its citizens to come and go, and was generally seen abroad as place that was Socialist but acceptable. So keen on Yugoslavia's "soft Communism" was Washington that the U.S. poured billions of dollars into the economy to support it (via Foreign Policy).

When Tito died in 1980, it seemed as if Yugoslavia would last forever. As testament to Tito's vision, prime ministers from Britain and France stood alongside Eastern European dictators at his funeral. (Vice President Walter Mondale and Saddam Hussein were also present, which must have been weird.) Even when Communism collapsed, it seemed Yugoslavia would survive in some form, maybe minus a Slovenia or a Croatia, but still essentially whole.

You probably know what happened next.

In June 1991, tiny Slovenia declared independence, kicking off a ten-day war that killed fewer than 100 people but lit the spark for Balkan conflagration. Croatia then went to war, Bosnia collapsed into civil war, Kosovo split from Serbia in a bloody conflict, and Macedonia was rocked by an ethnic insurgency. By 2008, Yugoslavia was seven separate countries and over 133,000 were dead. Sadly, Tito's vision couldn't survive without Tito himself.

The end of Communism would mean the end of history

Francis Fukuyama is famous for a single prediction. In 1989, he announced we'd reached the end of history. The Cold War was on the brink of ending and American geopolitical might seemed assured. Facing this generational shift, Fukuyama wrote (quoted here via The Guardian):

"What we may be witnessing is not just the end of the Cold War, or the passing of a particular period of post-war history, but the end of history as such: that is, the end point of mankind's ideological evolution and the universalization of Western liberal democracy as the final form of human government."

Hear that? That's the sound of future generations guffawing into their history books. Despite the huge popularity of Fukuyama's essay and 1992 book, recent events have proved that, far from "winning" anything, Western liberal democracy appears to be in crisis.

The Atlantic called this as early as 2014. Flash forward to 2017, and everyone can see it. Voters in the West are exchanging free trade for nationalist, isolationist movements. Putin's Russia is desperate to restart the Cold War. A theocratic caliphate managed to take over an area the size of Belgium in the Middle East by espousing a philosophy more medieval in outlook than actual medieval philosophers. In Asia, China seems poised to become the next superpower by mixing a hybrid capitalist-Communist system with really solid PR. Ever onward we go.

The USSR could have survived indefinitely

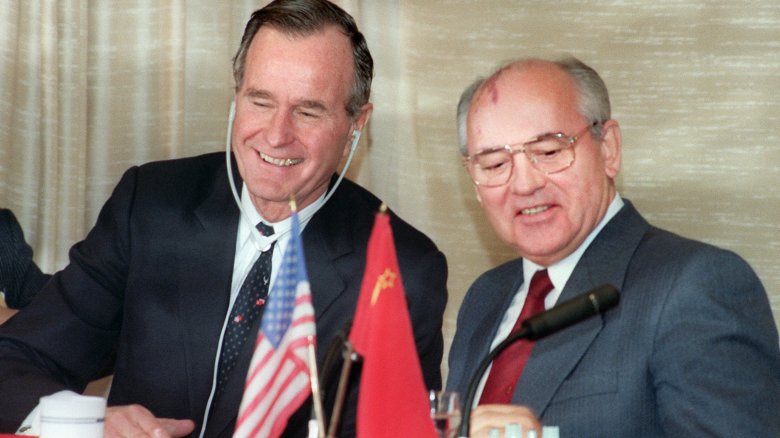

The total collapse of the Soviet Union at the beginning of the '90s caught everyone off guard. It had been clear since 1985 that things were changing, what with Gorbachev's reforms and Rocky KO-ing Ivan Drago, but no one expected the planet's second superpower to go completely kaput. The thinking was that the USSR was here to stay. Relations might get better or they might get worse, but the only way the Soviet empire was vanishing was in a cloud of radioactive dust.

So fast was the USSR's demise, in fact, that it still seems a fluke. Maybe if Gorbachev had reformed a little slower, or Ronald Reagan been a little weaker, or the GDR hadn't opened the Berlin Wall in panic, the Soviet Union would have managed to hold together. Political scientist Bruce Bueno de Mesquitawould disagree. In 2002, he applied tried-and-tested statistical forecasting models to the knowledge we had of the USSR prior to 1990. He concluded that there were enough factors in play to accurately predict the Soviet collapse as early as 1980.

Impressively, it's only the imminent dissolution of the USSR we could have predicted from 1980. In terms of predicting who would win the Cold War, de Mesquita's model could have called it for the USA in 1948. His 1998 article using data available just after World War II predicts Allied victory with a 68 to 78 percent probability, a technical way of saying the Ruskies were doomed from the get-go.

Soviet countries were gray, grim places with gray, grim-faced people

The words "former Soviet state" are the best way to instill instant foreboding about any vacation. You've doubtless got a mental image of Communist countries, and it doubtless involves gray-faced people shuffling around gray cities in gray weather, while wearing clothes that match the gray, gray skies above. As travel guides will tell you, the reputation of ex-Socialist states like Poland can even now be summed up with the single word "grim."

While decaying tower blocks filled with impoverished people definitely exist in Eastern Europe, they also exist in Chicago, Detroit, and, like, all the other cities. Away from the urban decay, places like Poland, Ukraine, Czech Republic, and Hungary are now and have always been beautiful.

After decades of propaganda promising that life under Communism was relentlessly ugly, the reality of cities like Budapest or Krakow can still be jarring. Prague, for example, is today so renowned that a recent poll of travelers ranked it prettier than Venice. The Polish port city of Gdansk used to have a reputation in the West befitting a place with "dank" in its name. Then Poland opened up, and we got to see Gdansk (pictured above) as it really was. Today, travel sites have whole lists of gorgeous buildings in this former Communist port, each one prettier than anything the entire state of Nebraska could summon. And we haven't even touched on places like Ukraine's Carpathian landscapes or the unlikely beauty of rural Albania. (Not sarcasm!) Consider your next vacation planned.

Communism was a single, monolithic entity

At the height of the Cold War, it was generally agreed that having any form of Communist government in your neighborhood was like inviting Moscow to set up a missile launch pad on your front lawn. This attitude only made sense through a prism of paranoia. Rather than being a single entity dedicated to the destruction of democracy, the Socialist nations were extremely diverse and far more likely to spend time undermining one another than undermining Washington.

Sometimes, this mutual backstabbing went to ludicrous extremes. In Albania, for example, Enver Hoxha was so convinced the USSR was going to invade that he built over half a million nuclear bunkers to shelter in (via Atlas Obscura). Since Moscow had just invaded Czechoslovakia, he may even have had a point. In Yugoslavia, Marshal Tito fell out so hard with Russia that Stalin tried to kill him with plague, while Tito may have had Stalin poisoned (via Daily Beast).

But it was in Asia where the workers' unity really collapsed. Communist Russia and China went to war in 1969, and at least one Chinese historian claims Russia came close to dropping an atomic bomb on its upstart neighbor. Communists in Vietnam invaded Cambodia to depose Pol Pot's Socialist regime and restore democracy. Around the same time, as Time notes, Vietnam and China also went to war, killing around 50,000 in six weeks. You know what they say, with friends like this...

Communists were always the enemy

Geopolitics is a messy business. During the Cold War, Western media might have tried to act like Communists were always the enemy, but even at the time this was clearly untrue. That's not meant in some airy, fairy "everyone's a good person" way. At various points in the Cold War, NATO countries were working with and actively courting Communist leaders — including some who were so far off the deep end that calling them bats–t would be an insult to guano.

The guano-iest of all was doubtless Romania's Nicolae Ceausescu. A man who was to sanity what nitro is to glycerine, Ceausescu ran the cruelest, craziest government in Eastern Europe, starving his people to death so he could build a giant super palace. Yet Western leaders accommodated and worked with him because his Romania stayed independent from Moscow. The British even invited him on a royal visit (above) that culminated in the Queen giving him a knighthood. The honor was only rescinded the day before his execution (via The Guardian).

Before any American readers start shaking their heads about those crazy Brits, it should be noted that Washington was at least as willing to work with Communist regimes as London. The U.S. pumped crazy money into Tito's Yugoslavia, while also helping shore up some mad dictators. According to PBS, Jimmy Carter — of all people — helped Pol Pot's Khmer Rouge keep Cambodia's seat at the U.N. after their overthrow, and helped fund their fight against the Vietnamese. Awkward.

Only capitalist nations could produce great cultural works

In the Cold War, Americans were taught that Socialist art meant singing about tractors and wheat production while the censor sent anyone with any individuality to the gulag. It's even alleged the CIA bankrolled Jackson Pollock's exhibitions to prove American individuality produced greater art (via BBC). This illusion only lasted so long as no one in the West was willing to experience Socialist art firsthand. So many great Eastern Bloc artists created strikingly individual works that it's hard to know where to start.

You could begin by checking out Czech New Wave cinema, which Empire has called one of the "movie movements that defined cinema." Or you could look into the similarly regarded Polish School. Or you could watch Dziga Vertov's Man With a Movie Camera, a USSR film so experimental it'd give Frank Zappa nightmares.

But hey, why stop at film when there's literature, too? One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich may have been (justifiably) critical of the Soviet regime, yet, as the BBC notes, the Soviet authorities still allowed its publication. Or you could look at the experimental 1980s art Timur Novikov produced in St. Petersburg. Or you could just kick back with The Master and Margarita, a satirical novel on Soviet life that was still somehow okayed for publication by the Soviet censor.

Many of these works were made in spite of Communist censorship, rather than because of it. But their existence shows creativity still flourished in the Eastern Bloc.