What Happened To British Union Of Fascists Leader Oswald Mosley After WWII?

Oswald Mosley is not as famous outside his native Britain as other 20th-century European fascists who made it into power: Benito Mussolini, Francisco Franco, or Adolf Hitler. But the name Mosley still casts a shadow over British politics, and a recent appearance as a villain in the historical crime drama "Peaky Blinders" suggests that interest in the figure is likely to grow.

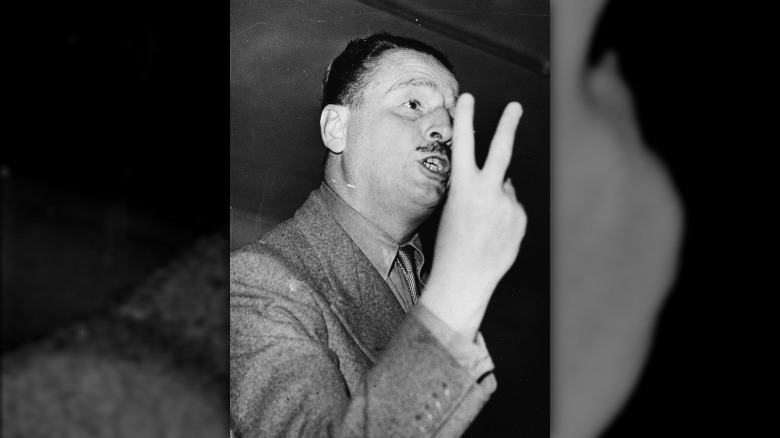

Mosley was born into an aristocratic English family, served in World War I, and entered British politics in the 1920s, becoming one of the youngest members of the British Parliament. Though his career was checkered by absences from politics, he earned respect for his oratory prowess in the House of Commons and for his thoughtful proposals based on Keynesian economics, known as the Mosley Memorandum, though his ideas were rejected by the Labour government at the time. But as the young parliamentarian became more disillusioned with the British political system, his conception of what underpinned the problem of society — and how these problems should be addressed — changed dramatically.

By 1931, Mosley had abandoned the traditional political parties of the U.K. in favor of the New Party, a group he founded with authoritarian intent. The following year, he merged with a flagging fascist group to become the British Union of Fascists. Modeling his rallies on those of Mussolini and Hitler, Mosley quickly gained sizeable support and, for a while, looked likely to be able to pressure the British government into attempting to broker a peace deal with Hitler's hyper-aggressive Nazi Germany.

However, all that changed after war was declared.

Mosley's internment and early release

According to the anti-fascist historian Morris Beckman, at the point that it became clear that Nazi Germany could not be contained, Oswald Mosley and the British Union of Fascists (BUF) — who had been identified as a potential threat and criticized in Parliament for their antisemitism as early as 1931 — were finally treated as an overt security risk. Mosley and the BUF had previously spread Nazi propaganda, and with a Nazi invasion of the U.K. a real possibility, Beckman claims that the British government realized that homegrown fascists were likely to become the enemy within.

Mosley, therefore, was interned in May 1940 as a potential security risk, though, as noted by the Bristol Radical History Group, he didn't remain in confinement for the duration of the war. In fact, he was released as early as 1943. The same source claims that Mosley's wife, Diana, had personally lobbied the wife of Churchill himself for Mosley's freedom, having convinced the Churchills that Mosley was sick with phlebitis. His release caused an uproar, not least because though the BUF had been banned, the U.K. still contained a considerable fascist presence, despite the horrors that war had inflicted.

Fascism by another name

Morris Beckman notes the surprising fact that, at the end of World War II, only two European countries remained marred by fascist organizations within their borders: Spain and the U.K. And even though Oswald Mosley's totalitarian heroes, Hitler and Mussolini, were both now dead, in 1945, the British Union of Fascists (BUF) leader was ready to rally his base and adjust to the new post-war political landscape. According to the Journal of Contemporary History, following the end of the war, Mosley told a gathering of his supporters that his fascistic ideas had been strengthened by the war and internment rather than altered by them, as evidenced by his continued publication of his fascist writings from the 1930s.

Per The New European, Mosley realized that the tyrannical optics of the BUF were no longer suited to winning the support of the British public after a long and bloody war against Nazi Germany, and from 1946, he took a different approach. He formed the Union Movement, a political project with a vision to create a pan-European government three decades before the formation of the European Union. This chapter in Mosley's political career may sound surprising to us today, as support for the EU is now typically considered a left-wing stance. However, as The New European notes, rather than precede the EU's ideal of "unity in diversity," the vision of the Union Movement was far from egalitarian and included some horrendous potential policies, including the expulsion of all European Jews to Palestine.

Holocaust denial

Oswald Mosley's antisemitism had been overt since the early 1930s, and indeed had been instrumental in his expansion of the British Union of Fascists (BUF). As Morris Beckman notes, the BUF intentionally wielded antisemitism to gain popular support among frustrated Britons, encouraging them to scapegoat Jewish communities for the problems of the country. And even as the horrors of the Holocaust became apparent after the fall of Nazi Germany in 1945, Mosley's hatred continued unabated, only now it assumed a new form: Holocaust denial.

As noted by The Jewish Chronicle, historians have noted several sources for the emergence of Holocaust denial in Europe following the discovery of the Nazi concentration camps, and among them is Mosley. Alongside his denunciation of the Nuremberg trials, he openly questioned the existence of concentration camps at Buchenwald and Belsen, derided pictorial evidence of gas chambers and mass murder, denied Hitler himself could have had any knowledge of what occurred at the camps, and argued that the poor conditions at the camps he was willing to concede actually existed were caused by "Allied bombing and consequent epidemics."

Political failures

In the summer of 1958, London was rocked by the Notting Hill riots, a period in which groups of white Britons racially assaulted the neighborhood's newly established Caribbean community, which at the time was made up of around 5,000 people who had settled in the area in the previous decade, per The British Newspaper Archive. Ever ready to exploit racial tension for political gain, Oswald Mosley decided that the aftermath of such violence created an opportune milieu for a Parliamentary comeback. Per The British Newspaper Archive, he and the Union Movement had been rallying anti-Caribbean sentiment for years following the arrival of the first post-war generation of Caribbean migrants in the U.K. via the famous cruise ship Empire Windrush. Consequently, he made strict anti-immigration policies the core of his message as he campaigned in the 1959 general election to become a member of Parliament for Kensington North.

However, according to the Journal of Contemporary History, Mosley and his supporters had vastly overestimated the level of support the Notting Hill riots might generate for their cause. He took just 8.5% of the vote, meaning he suffered the indignity of losing the deposit he had paid to become a candidate. He suffered a similar failure in 1966.

Exile and death

Oswald Mosley never again succeeded in reentering British politics. Having previously lived in Ireland, where he kept two homes, he and his family retired to France, where he lived out the rest of his life writing memoirs. He died in 1980, at the age of 84.

As noted in a scathing obituary published in The Washington Post — which highlighted Mosley's lifelong antisemitism and destructive influence on British society — in the final years of his life, Mosley had attempted to justify his fascist beliefs in a late autobiography, published in 1972. The same newspaper reviewed the book at the time, with reviewer Kenneth Rose calling Mosley's recollections "a grotesque, ghostly giggle from an appalling past[,]" adding: "There is a formidable weight of evidence to disprove Mosley's defense, and I for one remain unconvinced of the fundamental benevolence of British fascism." His children have since worked to distance themselves from their father's beliefs, with his son, Nicholas, writing two especially critical biographies of him.