The Untold Truth Of The Great Barrier Reef

A vibrant wonderland of interweaving coral reefs, technicolor fish, rainforest-capped islands, and warm tropical waters, the Great Barrier Reef is every traveler — and ocean creature's — dream. According to Britannica, northeastern Australia's pride and joy is both the largest and longest reef system in the world.

It's about 1,250 miles long — the distance from Vancouver to the Mexican border — with an area of 135,000 square miles, meaning it's a little bigger than Italy (per Britannica). As the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority notes, it stretches across an incredible 14 degrees of latitude, encompassing habitats from coastal estuaries to the deep sea. They don't call it great for nothing! In fact, the Great Barrier Reef is so impressive that it was added to UNESCO'S World Heritage List in 1981 (per Britannica), and CNN designated it as one of the Seven Natural Wonders of the World, putting it right up there with the Grand Canyon and Mount Everest (per World Atlas). Along with its greatness comes a history steeped in lore, and the Reef is still giving us plenty to wonder about to this day. From epic shipwrecks to a starfish-killing robot to the recent devastating coral bleaching events, here is the untold truth of the Great Barrier Reef.

It's the biggest structure made by living organisms on Earth

The Great Barrier Reef is so massive that it's visible from space (per Live Science). According to the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority, its singular name is kind of misleading — it's actually a complex system made up of 3,000 reefs, 300 cays, 600 islands, and several seagrass beds. Still, per Britannica, its skeleton has been fashioned over the course of many years by complex living creatures: coral.

Surprisingly, the animals responsible for creating massive coral reefs are ridiculously small themselves. According to the Living Oceans Foundation, it all starts when a coral larva attaches itself to a hard object on the seafloor. There it morphs into a polyp — a fleshy tentacled creature related to jellyfish and sea anemones — that soon divides, surrounding itself with an army of clones. Per National Geographic, they unite at the base, eventually forming a protected calcium carbonate colony that functions as an individual organism. Over the course of hundreds or even millions of years, coral colonies expand and merge with one another, eventually forming a reef.

But that's not the whole story. As Smithsonian Magazine notes, most coral is actually a complicated combination of animal, plant, and mineral. The polyps allow algae to live inside their limestone skeletons so long as they pay rent in the form of the sugars, nutrients, and oxygen they produce through photosynthesis. The algae tenants give coral its color — without them, a coral reef would not be the wondrous rainbow we know and love.

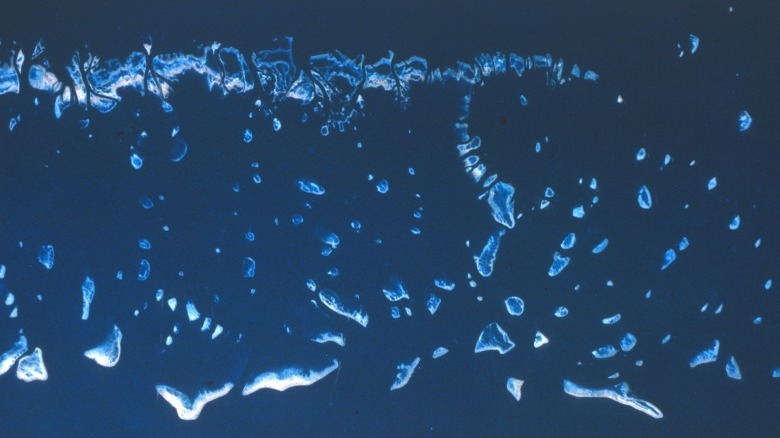

It's actually pretty far from shore

The coral reef that springs most easily to peoples' minds hugs the immediate shoreline of a continent or island and is easily accessed from a beach. According to the National Ocean and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), such a structure is known as a fringing reef and is the most common type of coral proliferation. The Great Barrier Reef is a rarer variety. As its name suggests, it is a barrier reef, meaning it borders the shoreline from a much greater distance and is separated from mainland Australia by a wide, deep lagoon (the dark blue water at the top of the photo).

Per Britannica, the Reef is anywhere from 10 to 100 miles offshore, depending on where you access it — a tad farther than most people can swim. According to Barrier Reef Australia, a Great Barrier Reef travel agency, it takes around 45 minutes to reach the closer islands by way of a motorized catamaran. To reach the Reef itself takes 70 to 90 minutes one way — unless you take a helicopter, in which case you can get there in a snappy 25 minutes.

At around 500,000 years old, it's young for a reef

Reef formation is complicated, and you'll be hard-pressed to find a scientist who knows exactly how old the Great Barrier Reef is. According to Science, it likely started forming as early as 500,000 years ago, though some coral remnants on the outer shelf are up to 1.05 million years old. The oldest areas of the Reef likely formed when the Earth's magnetic poles last reversed around 790,000 years ago. Compared to other reef systems — such as the Pacific atolls that formed over 45 million years ago — the Great Barrier Reef is a relative youngster.

The current Reef structure we know and love formed more recently, around 9,000 years ago (per the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority). Following the end of the last ice age around 20,000 years ago, sea levels started rising, reaching their current levels around 6,000 years ago. A large coastal plain once part of mainland Australia flooded, creating ideal habitat for coral, which grew along the crests of the plain's submerged hills.

But, as a 2018 study published in Nature Geoscience notes, it wasn't a cut and dry process. Much of the reef died five times in the last 30,000 years as its coral colonies battled sudden sea level changes and suffocation by sediments in a constantly changing world. The reef migrated back and forth over time to keep coral in optimal conditions for growth as water levels rose and fell.

It has caused many shipwrecks

With its treacherous protuberances lurking just below the surface, the Great Barrier Reef has claimed the lives of many seafarers. Even explorer Captain James Cook almost fell victim to it during his famous world travels. According to Cook himself in "Captain Cook's Journal During the First Voyage Around the World," his ship, the HM Bark Endeavour (pictured), ran aground on June 11, 1770. Cook noted that at around 11 p.m. on a moonlit night, "the ship struck and stuck fast." It began taking on water, and the crew moved the heavy anchors to a longboat before throwing everything from guns to casks overboard to lighten the load. Miraculously, following a panicked day of pumping water, the ship once again set sail on a rising tide.

As it turns out, Cook and his crew were the lucky ones. According to Australian Geographic, over 1,200 ships have wrecked on the Great Barrier Reef in the last 230 years. The frigate HMS Pandora — a Royal Navy ship hunting Bounty mutineers — crashed into the Reef and sank in 1791, killing 36 people. Almost a century later, the passenger steamship SS Gothenburg was swept into the Reef during a cyclone in 1875, taking 113 people and a bunch of gold with it. Deemed Australia's Titanic, the steamship SS Yongala — along with all 122 of its passengers — vanished without a trace in 1911. It was eventually discovered in the 1950s, and the wreck is now a thriving coral reef of its own.

It's one of the most biodiverse natural ecosystems on Earth

Called the rainforests of the sea (per NOAA), coral reefs are teeming with life of all kinds. The Great Barrier Reef is the biggest — and, per a 2019 study published in Marine Biodiversity, most important — of these biodiverse natural hotspots. As a 2018 study published in PeerJ notes, over 12,000 animal species call the Reef home, and countless plankton and other microscopic organisms proliferate in its waters.

According to the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority, this includes around 1,625 species of fish (over 10% of the world's fishes), over 3,000 mollusks, 1,300 crustaceans, 950 crust-forming bryozoans, 720 tunicates, 630 starfish and sea urchins, 500 worms, over 450 hard corals, 215 birds, over 150 soft corals and sea pens, 133 sharks and rays, over 100 jellyfish, 30 whales and dolphins, over 25 marine insects and spiders, 14 sea snakes, and six sea turtles. Dugongs — marine mammals related to manatees — can also be found grazing in the shallow seagrass beds, while saltwater crocodiles prowl in coastal estuaries and around the Reef's islands.

As the UN Environment World Conservation Monitoring Centre notes, 2,195 plant species also inhabit the Great Barrier Reef both in its waters and on its rainforest islands, including over 500 species of algae, 37 mangroves (over 50% of the world's mangroves), 15 seagrasses, and an endangered orchid.

The Great Barrier Reef is an important breeding site for endangered sea turtles

Dubbed the ancient mariners of the sea, sea turtles have been swimming in the world's oceans since the dinosaurs existed. According to the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority, six of the world's seven sea turtle species can be found on the Great Barrier Reef, and, of these, four regularly breed within the Reef.

Sea turtles live most of their lives in the ocean. When they reach 20 to 50 years of age, they make voyages of several thousand miles to breed. Females return to the exact beach on which they hatched to lay their eggs, despite not having been there since birth. Using her front flippers, a female sea turtle pulls herself up the beach to a dry area. She then digs a nest, lays her eggs, and buries them with sand before returning to the sea. Throughout one summer, a single female may lay up to three to seven clutches, each containing up to 120 round eggs. The eggs hatch after 12 weeks, and the young turtles quickly find their way to the water, where they lead mysterious lives on the open ocean. Per NOAA, only one in 1,000 or one in 10,000 survives to adulthood.

Raine Island — a small coral cay located at the northern tip of the Great Barrier Reef — is the largest remaining breeding site for endangered green sea turtles in the world and has been for 1,000 years, as per the Queensland Government. According to CNN, drones observed 64,000 female green sea turtles migrating to the island in 2020.

It was almost exploited by industries

The Great Barrier Reef came dangerously close to destruction in the 1960s. According to marine scientist Eddie Hegerl (via the BBC), there was a proposal to mine a section of the Reef's coral for limestone in 1967. Claiming the coral was already dead due to a cyclone, the mining company appealed to the Queensland government, which at that time was very industry-focused and thought mining the Reef would be a great way to create jobs.

Hegerl and his colleagues performed a survey of Ellison Reef — the area in question — and found it to be perfectly alive. Seeing the potential for widespread mining attempts, a major conservation effort was launched, with tourism put forth as a much better means of profiting off the unique region. This saved the Reef from becoming cement in southeast Asia or, per the National Museum of Australia, agricultural lime.

But the troubles weren't over. According to the National Museum of Australia, the Queensland government opened the entire coastline for oil exploration in 1968. By 1970, plans were already in place to begin drilling on the Reef. Following a series of disastrous oil spills and another conservation campaign, the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park was designated in 1975, granting the Reef permanent protection from exploitative industrial endeavors.

It's a major tourist attraction

The Great Barrier Reef draws travelers from all over the world. According to Live Science, around 2 million tourists visit each year, bringing an annual 6.4 billion AUD (over 4.5 billion USD) to the Australian economy and providing around 64,000 jobs (per the Great Barrier Reef Foundation).

It's truly incredible how many activities the Reef supports. As Queensland.com notes, you can snorkel the shallower reefs to find clownfish, scuba dive to get a closer look at a giant clam, or cruise around in a glass-bottomed or semi-submersible boat if that's more your jam. You can also swim with your choice of dwarf minke whales, sea turtles, manta rays, or, per Barrier Reef Australia, Wally the friendly Maori wrasse (don't worry, he comes in peace).

Per Queensland.com, other great activities include kayaking, learning how to spearfish, greeting migrating humpback whales, riding a tram over a rainforest, and watching baby sea turtles hatch. If you're feeling ambitious, you can rent a yacht, a private helicopter, or an entire island. And in addition to a plethora of resorts, you can also camp on the beach, in an island rainforest, or on the Reef itself by way of a floating pontoon.

It's the site of one of the weirdest, saddest, and scariest mysteries

On January 25, 1998, American tourists Tom and Eileen Lonergan joined a scuba diving tour. According to The Guardian, the trip included three dives on the Agincourt Ribbon Reefs (pictured), which lie on the seaward edge of the Great Barrier Reef around 40 miles from the mainland. After the last dive, the boat motored back to port. But the Lonergans weren't on board. It wasn't until January 27 — two days after the ill-fated trip — that the skipper found the couple's belongings on the boat and realized something was wrong.

A massive three-day search ensued, but no sign of the couple was found. A coral-torn wetsuit thought to be Eileen's washed up a few weeks later, with barnacle growth on its zipper indicating it had been at sea since January 26. Later, inflatable dive jackets featuring their names, their air tanks, and one of Eileen's fins came ashore. One hundred miles away, a fisherman found a dive slate marked with a desperate written plea dated January 26, 1998, at 8 a.m.: "To anyone who can help us: We have been abandoned ... Please help us come to rescue us before we die. Help!!!"

They were never seen again. While theories circulated that the couple faked their deaths or enacted a murder-suicide pact (per All That's Interesting), experts believe they likely succumbed to dehydration, which could have caused them to strip off their gear in delirium (via The Guardian). The 2003 film "Open Water" was based on the tragedy.

Climate change is killing the Great Barrier Reef's coral

Tropical reef coral requires pretty specific parameters to thrive. It must receive enough light for its symbiotic algae to perform photosynthesis, so it can't live too deep — but at the same time, it can't survive in water that is too warm (per NOAA). According to CNN, there have been six mass coral bleaching events in the last two decades. The first occurred in 1998, followed by another in 2002. Since then, they have gotten more frequent, with back-to-back bleachings in 2016 and 2017, another in 2020, and, most recently, a major event caused by several heat waves in 2022.

According to NOAA, coral bleaching most often occurs when warmer than average ocean water sets off an unfortunate chain reaction. In such conditions, algae begin to malfunction in the heat, producing toxins (via New Scientist). Stressed polyps are then forced to evict their plant roommates, causing them to turn white. Coral cannot stay bleached for long, as without the algae, they have no food source. If conditions do not improve, the polyps within soon starve and die.

As NPR notes, Australia's waters saw temperatures 7 degrees higher than average over its 2022 summer — a major stressor for the Reef's coral. As a result, coral bleaching was observed in around 60% of the Great Barrier Reef's corals in 2022 (per The Washington Post). Warming ocean temperatures are the result of human-caused climate change, and unless we can reduce fossil fuel emissions in the coming days, most of the world's reefs will die. As marine biologist John Bruno told The Atlantic, "It's like clear-cutting a redwood forest."

It has a complicated relationship with a starfish

With its 3-foot diameter, the spiky crown-of-thorns starfish is the second largest starfish in the world (per the Great Barrier Reef Foundation). According to The Washington Post, it's also the most fertile invertebrate on Earth — a single female can lay 65 million eggs per year. Oh, and it eats coral. Just 30 starfish within a 2.5-acre area can devour an entire reef, but lately, as many as 1,000 starfish have been seen on an area of that size. The voracious echinoderm is the second biggest threat to the Great Barrier Reef behind climate change.

Normally, the starfish don't pose a problem. In fact, according to the Great Barrier Reef Foundation, they are a healthy part of the ecosystem, feeding on fast-growing corals so the slower-growing species can gain a foothold. But, as Anna Marsden, the director of the Great Barrier Reef Foundation, told The Washington Post, fertilizer from agricultural runoff is feeding phytoplankton, creating a ton of food for starfish larvae. Overfishing has also removed many of the starfish's predators — like the giant triton snail — allowing for unchecked population booms.

Divers hunted the starfish for a while, but this barely put a dent in their numbers. So, according to Bizarre Beasts, scientists developed an underwater robot to do it for them. To avoid "Terminator 2" style mayhem, the robot was trained to identify crown-of-thorns starfish using a collection of images and videos. Once released, it diligently patrolled the Reef, delivering lethal injections of bile — toxic to starfish but nothing else — to any hapless crown-of-thorns it found. As a bonus, it's also being used to seed reefs with coral larvae.

You can visit the Great Barrier Reef virtually

According to their website, the Catlin Seaview Survey is a joint venture between Underwater Earth, the University of Queensland, and AXA XL that uses sophisticated custom-built underwater cameras to produce 360-degree panoramic images of the world's reefs. These detailed images create a baseline record of aquatic ecosystems that can be used in scientific studies. They also enable anyone terrified of scuba diving to enjoy the beauty of deep-water reefs virtually.

According to Live Science, Google Maps partnered with the Catlin Seaview Survey in 2012 to create several street view experiences around the Great Barrier Reef. Points of interest include Lizard Island, Lady Elliot Island, Green Island, Heron Island, and Lady Musgrave Island. Simply drag the yellow avatar to one of the virtual dive sites, and Google plunges you below the sea, where you can study the ocean floor, explore coral up close, pop into a school of fish, and even swim with sea turtles — all from the comfort of your home! Ah, the magic of technology.

It still holds hidden treasures – maybe even a cure for cancer

The Great Barrier Reef is vast, and we still haven't uncovered all of its secrets. Per Australian Geographic, biologists discovered the first new species of branching coral in over 30 years on the Reef in 2017. In 2020, researchers found a knife-shaped reef as tall as the Empire State Building 80 miles off Australia's coast (per Discovery). And according to The Guardian, divers located a 400-year-old coral colony the size of a double-decker bus on the Reef in 2021.

Scientists believe that the greatest discoveries may come from within the Reef's creatures, whose hard-knock lives have led them to develop powerful compounds. Deemed the medicine cabinets of the 21st century (per NOAA), coral reefs have led to the discovery of over 20,000 chemicals that may soon become medicines (per KCET). Compounds found in a Caribbean coral led to an anti-inflammatory drug, a Florida reef microorganism contains antiretrovirals that may help combat HIV, and a reef-dwelling sea snail produces a powerful non-opiate painkiller. Chemicals found in a Caribbean sea sponge were even used to produce the life-saving anticancer drug Ara-C.

Parts of it saw record coral cover in 2022 – but hold the celebration

According to the Australian Institute of Marine Sciences (AIMS), parts of the Great Barrier Reef showed the highest percentage of coral cover seen in the last three decades, the first piece of good news involving the Reef in years. A survey of 87 reefs showed that, on average, hard coral cover had increased by 7-9% over the last year in the central and northern portions of the Reef — proof that coral has some capacity to recover from devastating events.

Still, according to AIMS, coral cover merely measures how much hard coral covers a reef, not what species make up that cover. As The Conversation notes, this makes the data deceptive. Fast-growing corals of the genus Acropora (pictured) are great at rebounding following a catastrophe. With their branching and plating growth habit, they also take up a lot of space, meaning a coral cover survey could show mostly Acropora — which the recent surveys do.

The problem is that's only a handful of species. According to The Conversation, an examination of 44 years' worth of coral records from Lizard Island — an area that saw a recent increase in coral cover — suggested that 28 of 368 species had vanished from the area over at least the last 10 years and may be facing local extinction. Disturbances like heat waves could be reducing coral diversity. As marine biologist Terry Hughes tweeted, "You can't replace a dead 50-year-old coral in five years."

The Great Barrier Reef could be gone by 2050

In addition to warming waters and crown-of-thorns starfish outbreaks, the Great Barrier Reef faces many other threats, most of which are caused by humans. According to the Great Barrier Reef Foundation, toxic runoff, sediments, and ocean acidification — caused by excess atmospheric carbon dioxide, per NOAA — are reducing water quality. Coal mining, agriculture, and increased urban development in coastal areas could also pollute the Reef's water. Per the National Environmental Science Programme, widespread wave damage from tropical cyclones remains a constant threat, and such storms could become more intense in the near future.

The Great Barrier Reef — and all coral reefs — are in big trouble. According to Insider, human-driven greenhouse gas emission, which causes warming seas and ocean acidification, poses the greatest threat. Because emissions will only increase without intervention, 60% of coral reefs will probably be in critical condition by 2030 (per World Resources Institute). By 2050, most will likely be gone. This could have a devasting ripple effect on the world's oceans, and that's downright scary. As marine scientist Michael Crosby told Insider, "You like to breathe? Estimates are that up to 80% of the oxygen you are breathing in right now comes from the ocean."