The Tragic True Story Of The Nika Riots

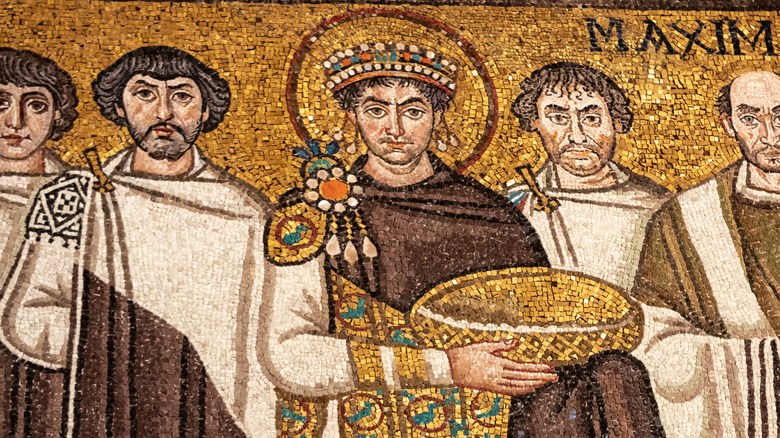

Emperor Justinian came to power in the Eastern Roman Empire (aka the Byzantine Empire) in A.D. 527. with one goal in mind: to reassemble the former Roman Empire, according to WBUR. He ruled from Constantinople and lived within a generation (just 50 years) of the fall of Rome and the Western Roman Empire. Historian Mike Dash explains, "[Justinian] felt, I think, fairly strongly that the Roman Empire had taken a huge hit before his reign, and that it was his duty, really, as emperor to try and reconquer as much of that as possible."

At the start of his reign, Justinian ruled alongside his uncle, Justin. But within four months, his uncle died, and he became the sole ruler, as reported by ThoughtCo. Like Uncle Justin, Justinian remained dogged by whisperings about his humble beginnings and unimpressive family history. Because he lacked titles and noble blood, he faced constant challenges from the Byzantine Empire's senators, some of whom didn't think he deserved their respect. Fanning the flames of discontent were many of Justinian's empire-building plans, which required near-constant military campaigns, increasingly burdensome taxes, and ambitious building projects.

As resentment bled through to all levels of society, the Eastern Roman Empire became a tinder box poised for a spark. This spark came in the form of chariot races held in mid-January of A.D. 532, leading to one of the most violent episodes in Constantinople, the Nika Riot.

The most violent event in Constantinople's history

The Nika Riot exploded at the Hippodrome where massive crowds gathered to watch chariot races, according to ThoughtCo. While the revolt in A.D. 532 was far from the first public unrest to break out at the Hippodrome, it left the deepest impression due to its culmination in an outright slaughter of the masses.

The name for the riot came from the Latin "Nika!," which adoring crowds screamed for their teams. Translated as a mixture of conquer, victory, and win, it took on new significance during the revolt. In the past, the crowd was split into manageable dueling loyalties to the Blues and the Greens, as reported by WBUR. Traditionally, the emperor chose between the two, and in previous competitions, Justinian had purportedly always sided with the Blues. But with tension palpable in the capital, he refused to support either side. This fatal error represented the spark needed to light the city on fire, literally. It also dangerously united both factions against the emperor.

Bringing the violence to a halt required a steady, fearless hand — not Justinian's strong suit. But Empress Theodora was made of a different mettle (via Smithsonian Magazine). She shamed him into remaining in Constantinople and fighting when exile held greater appeal. But this came at a steep public cost. Tens of thousands of men, women, and children perished once Justinian ordered his military to restore order to Constantinople, making it among the most violent events in the imperial city's history.

A controversial emperor and empress fueled discontent

To say Emperor Justinian was a controversial figure is an understatement, as reported by ThoughtCo. He inherited a powder keg of partisanship, and his best intentions only made things worse. His desire to return Rome to its former glory came with an astronomical price tag, which meant raising taxes on the citizens of the Byzantine Empire. The increase in taxes led to pain for average people and anger directed towards the emperor.

What's more, Justinian set out to end corruption within the government, as ThoughtCo notes, which proved an undertaking fraught with political and physical danger. Politically minded families had entrenched themselves in the nation's upper echelons over the course of many generations, and they weren't going to give up their power and influence easily. In his attempt to drain the Roman swamp, Justinian excited plenty of resentment, which reached the boiling point during the Nika Riots.

Besides heavy taxation and unpopular reforms, Emperor Justinian had also raised eyebrows by marrying a low-class courtesan named Theodora. The daughter of a bearkeeper, she rose to fame through entertainment of the most salacious sort. As the historian Procopius put it, "There was no shame in the girl, and no one ever saw her dismayed" (via WBUR). In fact, a law had to be put in place to even permit the marriage, as per World History Encyclopedia. But although she was cut from the same temptress' cloth as Cleopatra, she proved Justinian's unlikely savior rather than his stereotypical downfall.

A history of partisanship and violence

Rome had long entertained the public with gladiatorial matches and chariot races, per Smithsonian Magazine. Little had changed in the Eastern Empire. Gladiatorial competitions and chariot races drew massive crowds attracted to gory spectacle. Historian Mike Dash explains, "[Chariot races] were the NFL and the MLB rolled into one in terms of sporting entertainment" (via WBUR).

Chariot races involved up to a dozen four-horse teams racing at breakneck pace seven times around the Hippodrome. In the process, teams collided, and riders got mashed up in the fray. Gruesome injuries and deaths proved commonplace with charioteers thrown into the stone spina separating the racetrack's center or drug behind their chariots until their horses could be stopped. Many died in their early 20s.

As Smithsonian Magazine details, at the height of the Roman Empire, four teams competed in these contests: the Whites, Reds, Blues, and Greens. But by Justinian's time, the field had narrowed to two teams. Audience members turned out in support of their teams and to bet on who would win. Whether they favored the Blues or the Greens, many participated in nasty tricks, like throwing curse tablets onto the racetrack. Covered with nails, audience members hoped they would throw off enemy racers resulting in their teams' win. The violence pulsing beneath the surface of the partisan chariot races had generally remained confined to the Hippodrome. But the addition of a controversial emperor and unpopular policies threatened to change this.

A perfect storm of violence engulfed Constantinople

To achieve his goals of reconstructing the glory of the former Roman Empire, Justinian appointed an army of tax collectors headed up by John of Cappadocia, according to Smithsonian Magazine. Taxing the wealthy seemed to be the goal, with some 26 new taxes put in place affecting the Byzantine Empire's wealthiest citizens. As a result, John of Cappadocia soon rose to the ranks of one of the most hated men in the empire, per ThoughtCo.

Coupled with Justinian's harsh treatment of the Greens and Blues after fighting broke out on January 10, the emperor faced spiraling violence that spread rapidly, as reported by WBUR. The initial fighting broke out between the Blues and Greens like most Hippodrome riots. But unlike previous instances where the emperor took a side, ensuring the support of at least one faction, Justinian remained above partisanship. He sent in the Imperial Guard to restore order, and they seized seven perceived leaders of the revolt for execution.

Several days later, people gathered for the executions of the men. But in an odd turn of events, the gallows crafted for the job collapsed beneath the weight of those facing death. Two men were saved, after both the Blues and Greens joined together to help save them. United by the effort, both factions would remain united, next turning their frustrations on those in charge.

The next chariot race tipped off the conflict

At the next chariot race, all hell broke loose, as reported by WBUR. The crowd cheers of "Nika, nika!" weren't meant to inspire the charioteers. Instead, the chant spoke of the victory the Blues and the Greens realized they could achieve by uniting against the emperor.

The Hippodrome held a maximum of 100,000 people and was roughly four times bigger than a football field. This translated into a big problem concentrated in one location. The Hippodrome also contained a clandestine tunnel that headed straight to the Imperial Palace. This permitted Emperor Justinian and Empress Theodora to access the imperial box at their leisure, including their ability to slip away to safety during the escalating violence.

Officials responded by shutting down the Hippodrome in the hopes this would help the crowd disperse and go home. But this didn't happen. Instead, rioters spilled out into the streets where they started burning down Constantinople. As Procopius observed, "Fire was applied to the city as if it had fallen under the hand of an enemy." Two days passed with no slowing of the violence. Justinian and Theodora remained locked in the Imperial Palace, hoping the crowds would grow tired and eventually go home. At his lowest point, Justinian considered plans to flee the city (via Smithsonian Magazine).

Empress Theodora refused to leave

The Nika Riot lasted for nearly one week, per Smithsonian Magazine. By day four, rioters looked for Emperor Justinian's replacement. At the time, Justinian issued orders to Hypatius and Pompeius, nephews of former Emperor Anastasius, to leave the Imperial Palace and return to their homes, per ThoughtCo. Justinian had come to suspect the two young men's motives. Unfortunately, they got swept up as unwilling participants in the revolt when the mob descended on Hypatius' house, as per Procopius' "History of the Wars" (via Fordham University). Soon, he sat on the Hippodrome's imperial throne.

Justinian seriously contemplated leaving Constantinople at this point, and he had the wealth to do it. But Empress Theodora refused to go. In one of the most celebrated speeches ever spoken by an ancient heroine, she argued, "If you, my lord, wish to save your skin, you will have no difficulty in doing so ... But consider first whether, when you reach safety, you will regret that you did not choose death in preference. As for me, I stand by the ancient saying: the purple is the noblest winding sheet" (via Smithsonian Magazine). In other words, she was ready to live and die as an empress.

Whether Justinian felt shamed into action or his respect and love for his wife overcame him, it's unknown. But no matter the motivation, he heeded the empress' words, discarding all chances at escape. With Theodora's encouragement, he and his allies delved wholeheartedly into developing a strategy to regain control of the Hippodrome and the city.

Emperor Justinian made a dramatic appeal to the masses

In one of the gutsiest moves of the Nika Revolt, Emperor Justinian appealed directly to the people of the Byzantine Empire, per "History of the Later Roman Empire," by J.B. Bury (via the University of Chicago).

Addressing a huge crowd in the Hippodrome, he started by holding up a copy of the Gospels, using the collection of holy writings to swear an oath. Among the promises he made was full compliance with the demands of his subjects, as well as an amnesty extending to all of those involved in the insurrection. An incredible amount of bloodshed could have been prevented had the crowds listened to him. But those gathered wanted to hear nothing of it.

Instead, they hurled insults and accusations at him, screaming "You are perjuring yourself" and "Long live Hypatius!" But the emperor kept full command of himself. Having tried to deal directly with the citizens of Constantinople, he looked at other avenues to regain control of the empire.

Justinian resorted to insinuation and bribery

In the wake of the week-long riots, Constantinople appeared unrecognizable, according to "History of the Later Roman Empire," by J.B. Bury (via the University of Chicago). The mob had destroyed much of the city, including the Praetorium, the baths of Alexander, the hospices of Eubulus and Samson, and the church of St. Irene. One thing was for sure. Justinian had to find a way to end the Nika Riots, and he needed to do it quickly. After huddling with his allies, he developed a plan so sneaky it just might work. Realizing he needed to find a way to pit the Blues and Greens against each other once more, he sent out Narses, a faithful eunuch, with a coin-filled purse.

After slipping into the Hippodrome, Narses fraternized with the Blues, convincing many among their ranks through bribery and manipulation to abandon the fight. By turns, he reminded them that Hypatius' uncle had always supported the Greens, and it was naïve to think his nephew wouldn't do the same.

Next, he played on their nostalgia, reminding them that Emperor Justinian and Empress Theodora had always been robust supporters of the Blues. The faithful eunuch's insinuation into the crowd did the trick, and Blues vulnerable to persuasion began to give way, making way for the next step in Justinian's plan.

After bribery came the bloodbath

After Narses' attempt to soften up the resolve of the Blues, Justinian's military allies, Mundus and Belisarius, entered the arena, according to "History of the Later Roman Empire," by J.B. Bury (via the University of Chicago). Those among the Blues that hadn't heeded Narses' appeal would pay for it in a devastating way. Although Emperor Justinian had found no loyalty among the palace guards and other forces that traditionally supported the emperor, he still made the most of the forces available to him.

The troops under Justinian's leadership proved vastly outnumbered, but they were highly effective in the throng of tightly packed people. What's more, most were of Gothic or Thracian ethnicity, which meant they had no allegiances to either the Blues or the Greens, notes Smithsonian Magazine. Even though large parts of the crowd were also armed, they caved under the pressure of a professional military assault. The discipline and weaponry of Mundus and Belisarius won the day.

An estimated 30,000 civilians or 10% of the citizenry of Constantinople died that day, stuffed into the Hippodrome like sardines and unable to escape. Soon, the Hippodrome's stones ran scarlet with the wave of death unleashed by Justinian's allies. Procopius observed with the chill of a detached historian, "This was the end of the insurrection in Byzantium" (via WBUR).

Justinian punished his political rivals

Justinian's nephews, Justus and Boraides, understood that ending the conflict required destroying the perceived ringleaders, per "History of the Later Roman Empire," by J.B. Bury (via the University of Chicago). Unfortunately, this meant targeting Hypatius and his brother, Pompeius. Although it was well known that the men had been compelled by the mob to participate in the insurrection, Justinian also realized their existences represented serious threats to his rule ... however tenuous their genealogical grasp of the throne.

Despite Hypatius' and Pompeius' tears and pleas that they had no choice in the events of the week, they were murdered the next day. Unceremoniously, their bodies were thrown into the ocean. Only death ensured these potential political weapons would be laid to rest. But both men's families were allowed to live.

Emperor Justinian also made an example of 18 senators implicated in leading the conspiracy against him by seizing their property and banishing them. But Emperor Justinian wasn't one to hold grudges. In the aftermath of the riots, he pardoned all 18 senators, restoring their possessions to them. He also offered restitution to the children of Pompeius and Hypatius.

The Nika Riots strengthened Justinian's rule

The death toll in Constantinople proved devastating and so was the damage from the Nika Riots, according to ThoughtCo. Arrests continued well after the unrest, and many families lost everything as a result of their connections with seditious actors. Officials also realized that playing with fire eventually led to serious burns. So, they shut the Hippodrome down for half a decade, suspending chariot races during that time.

But not everyone in the Byzantine Empire would suffer after the insurrection. Justinian had showed his resolve and courage, and it wouldn't go unnoticed. He gained a massive amount of respect from the public while conveniently neutralizing most of his enemies. Realizing he would stop at nothing to maintain power, any remaining political rivals lacked the stomach to stand up to him.

The same went for Empress Theodora, as reported by ThoughtCo. She enjoyed newfound respect, going down in the history books as courageous and eloquent even as she faced death at the hands of an unforgiving mob. Over the next three decades, Justinian would continue his vision of reuniting the former Roman Empire, and he would also take domestic precautions to avoid future issues (via WBUR). This included creating laws to curb the senatorial class' power even as he undertook massive public works projects to rebuild the damaged city. Emperor Justinian and Empress Theodora's legacy would prove one of great controversy and impressive brilliance unmatched by any of their successors.