The Untold Truth Of Shark Week

Nothing is more fun than sharks in the summertime! Except for not getting eaten by sharks in the summertime, which is just about the best reason there is to stay indoors in air-conditioned comfort and watch Shark Week instead of going to the beach. Discovery Network's annual Shark Week event is one of the most loved, feared, and hated weeks on cable TV, and every year it inspires controversy, debate, rabid binge-watching, and cupcakes with shark fins sticking out of them. From celebrities swimming with sharks to programs providing the latest innovative research on shark species, the popular programming is ratings gold, with 2020 seeing nearly 27 million viewers tune in, according to Forbes.

So how exactly did Shark Week become the weird and wonderful phenomenon that it is? It's a long and sordid story, starting more than a quarter of a century ago.

The idea for Shark Week was floated sarcastically

Shark Week has been around almost as long as the Discovery Channel, which launched in 1985. Just two years later, network executives started wondering how they might be able to convince their potential summertime audience to stop enjoying the sunshine at the beach and veg in front of the television instead.

The most popular Shark Week origin story has executives raising the idea at a drunken after-work party and writing it down on a cocktail napkin (via Newsweek). But the most reliable account probably comes from Tom Siebert, who was a 20-something new hire at the fledgling network in 1987. According to Siebert, he raised the idea sarcastically during a brainstorming session: "Look, we know the bigger the animal, the bigger the ratings, and if it can kill you, that's the best. So why don't we just air shark shows all summer?" (via Media Post).

The funniest part about this version of the story is that Siebert wasn't even serious. He only threw out the idea because he was annoyed that the network was really just worried about their bottom line (duh), and he later recalled sitting aghast as the idea was actually discussed. That night the idea was passed along to Discovery's founder and CEO, John Hendricks, who was really into it, and now three decades later viewers all get to be pissed off every year because megalodons no longer exist, and Michael Phelps wasn't actually racing a real shark.

Shark Week is a ratings megalodon

Shark Week celebrates its 33rd year in 2021, notes Discovery — the event is cable's longest-running and also one of its most-watched. It consistently beats its own ratings records, and its total audience typically numbers in the tens of millions.

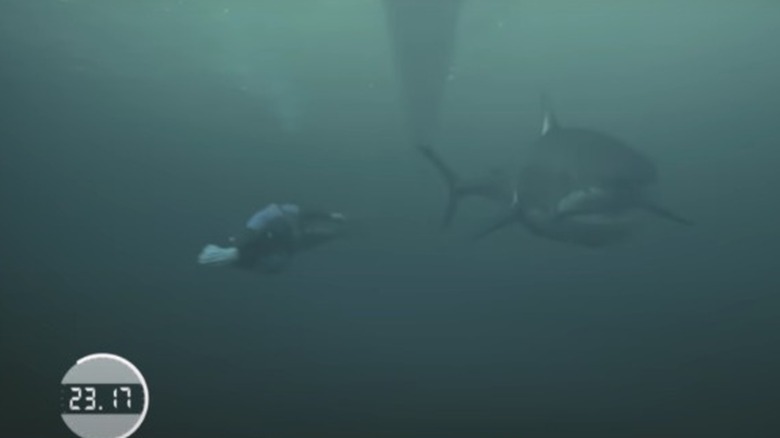

In its first year, Shark Week doubled Discovery's usual summertime ratings. According to The Week, in 2014, Shark Week attracted a total of 53.17 million viewers (the highest rating at the time since the inception of programming), and then ended up pissing most of them off with its infamous "Megalodon: The Monster Shark Lives" mockumentary. Undeterred, the network then went on to piss more people off in 2017 with its Michael Phelps vs shark program, which attracted nearly 5 million viewers. And yet, viewers always seem to forgive, returning to Shark Week year after year for programs with titles like "Zombie Sharks," "Great White Serial Killer Lives," and "Shark of Darkness: Wrath of Submarine."

Everyone wants to host Shark Week

Shark Week was hostless for the first few years, then in 1994 the network landed Peter Benchley, author of "Jaws," as its first host, according to USA Today. Benchley was celebrating the 20th anniversary of his best-selling man-eating shark novel, which was the basis for Steven Spielberg's 1975 blockbuster of the same name.

Benchley introduced each Shark Week program from a location where the famously terrifying movie had been shot, proving once and for all that Shark Week isn't about sensationalizing the ocean-dwelling predator, it's about science and education. After Benchley's appearance, Digiday reports that Shark Week has featured celebrity hosts regularly. Notable alums have included Mike Rowe from "Dirty Jobs," comedian Craig Ferguson, Rob Lowe, and supermodel Heidi Klum (because supermodels and sharks have so much in common).

Shark Week has some haters

Shark Week has some enemies, including marine activists and conservationists who want us to think that sharks are super nice, like kittens only with five rows of giant teeth and bloodstained lips. To be fair, though, Discovery has had to stand on both ends of the ratings teeter-totter — does it air sensationalized programming featuring blood, violence and death, or does it tell the often-boring but much more educational truth about sharks? For example, in 2014, ABC News reported that death by cow is about five times more common than death by shark. Sharks kill an average of four people annually, while cows gore or trample to death an average of 22 people. Audiences probably won't see the Discovery Network's historic launch of "Cow Week" any time soon, mostly because cows don't have the aforementioned five rows of giant teeth and bloodstained lips.

Conservationists are understandably concerned about the sensationalism — it seems like the network features more violence every year, which typically includes dramatized recreations of shark attacks. Such programming creates the false impression that sharks are more dangerous than they are, which has a negative impact on conservation efforts. The truth is that shark populations around the world are in decline, and most people don't seem to care. And although there's no proof that Shark Week is to blame, it's hard for a lot of people to internalize the idea that the great white that just ate some guy on Shark Week needs to be protected.

Shark Week does try to tell the truth ... mostly

Clearly, all those conservationists have never seen "Sharknado" (and its subsequent sequels), or they might know that the man-eating instinct is so ingrained in the shark psyche that sharks will attack anything that moves, even after falling thousands of feet out of a passing tornado. But hey, guess what, "Sharknado" is actually fiction. Yes, it's true, most sharks will actually die after a 50,000-foot drop, and any that survive wouldn't have much of an appetite.

Shark Week does occasionally make an effort to tell the truth about sharks, and this was especially true in the early years when the sensationalism was only in the titles of individual shows. Its very first episode, titled "Caged in Fear," was really just an in-depth look at the science and technology of motorized shark cages, reports Newsweek. Since then, the network has invested heavily in some of the world's best videographers and documentarians, capturing some amazing and unique footage that has changed our understanding of the way sharks live and hunt. And the network has never really lied about the nature of the shark attack: Humans don't live in the ocean, and as such are not on the sharks' list of approved snacks. "We hope that as we tell these stories, people hear the real message," former Discovery Channel president and general manager Clark Bunting told Time magazine in 2010. "The victims were in the wrong place at the wrong time."

No biologists were harmed in the making of Shark Week ... except one guy

In 2002 a biologist named Erich Ritter was filming a Shark Week special when he was attacked by a bull shark and nearly bled to death. Recalling the incident, Ritter was pretty gracious about the whole thing, explaining that the animal was primarily motivated by stress. "In the aftermath she took my calf muscle," he later told the New York Times. "It was very painful."

The attack on Ritter was the first shark bite on a human ever recorded on film, and Shark Week producers were all, "Cool, let's put that on the air." The attack was featured on a Shark Week special called "Anatomy of a Shark Bite" in 2003, the first year viewers didn't have to settle for dramatic recreations of shark attacks. They could see the real thing in high definition.

Ritter says his shark bite was actually proof that sharks aren't vicious, which is sort of like if you watched some guy get crushed by a falling piano and then called that proof that pianos aren't heavy, but whatever. Shark bites are rare and are mostly cases of mistaken identity, but showing real-life footage of one is probably not the best way to convince people that sharks are just misunderstood.

Shark Week makes people scared of sharks

Studies pretty consistently show that people who watch a lot of crime dramas overestimate their chances of becoming a victim of crime. So it's not really surprising that a similar study by researchers from Indiana University and the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, shows that people who watch Shark Week tend to overestimate their chances of getting eaten by a shark and continue to react with fear.

They had 500 people watch clips from Shark Week, from violent shark attacks to sharks swimming peacefully through the water, followed by a public service announcement that talked about the need for shark conservation. Researchers discovered (shockingly) that those short messages after the violent programming didn't seem to make people any less afraid of sharks.

Another study, published in Marine Policy, surveyed over 180 people on their shark knowledge and correlated that with support of conservation efforts. While the study did note that individuals "with more knowledge pertaining specifically about sharks had potential behaviors more supportive of their conservation," the media (with programs like Shark Week) does play a part in sensationalizing the marine animal and causing anti-shark sentiment.

So really, it seems like Shark Week is ultimately doomed to scare people, even if it shows nothing but sharks having tea parties and attending 12-step meetings, a la "Finding Nemo."

Shark Week was the first to show footage of breaching great white sharks

In what is probably the closest people will ever get to an actual sharknado, Shark Week was the first to give the world visual proof that great white sharks can jump out of the water like dolphins. Like terrifying, terrifying, terrifying, saber-toothed dolphins. According to Newsweek, in 2001, Discovery aired a Shark Week special called "Air Jaws: Sharks of South Africa," which showed the massive, 2,000-pound creatures leaping out of the water in slow motion, usually with doomed seals trapped in their maws. The special was so well received that "Air Jaws" is now a regular thing, with subsequent specials titled "Air Jaws: Walking with Great Whites," "Air Jaws: Apocalypse" and "Air Jaws: Night Stalker."

Despite the sensational titles of pretty much every installment of "Air Jaws," the series has proved popular with Shark Week viewers and critics — the 2010 episode, "Ultimate Air Jaws," was Emmy-nominated and the first to use the Phantom high-speed camera, which captured the breaching sharks at 2,000-frames-per-second, making that footage about 100 times more terrifying than standard video of breaching great whites.

Shark Week straight lied to you for ratings

Because ultra slow-motion video of airborne great white sharks and real-life shark bites aren't already more terrifying than fiction, in 2013 Discovery decided what Shark Week needed to do was make stuff up and call it a documentary, like if "War of the Worlds" was way less believable. The 2013 episode, "Megalodon: The Monster Shark Lives," was Shark Week's most-watched program of the year, but it was fiction. If you weren't tuned in for the disclaimer that flashed by at the end of the episode, you'd have had no idea that "None of the institutions or agencies that appear in the film are affiliated with it in any way, nor have approved its contents." In fact even the disclaimer was misleading — it said that "certain events and characters in this film have been dramatized," that "megalodon was a real shark," and that sightings "continue to this day," but it stopped short of saying "what you just saw was fiction."

Despite other clues that the documentary was fake, like really bad CGI and "scientists" who were obviously reciting scripted material, notes Oregon Live, some viewers believed what they were seeing. When they learned they'd been duped, they were pretty righteously pissed off. Even so, Shark Week's executive producer Michael Sorensen poo-pooed the backlash and praised the two-hour special as the "ultimate Shark Week fantasy." But by 2015, with the network still reeling from the bad press, executives told Vulture there would be no more fake documentaries.

Michael Phelps didn't really race a shark

In 2017 Shark Week promos hyped another monster event: 23-time gold medalist Michael Phelps was going to race a great white shark! Now, in all fairness, anyone who stopped to think about it for more than five seconds should have realized that it would have been impossible for Phelps to race an actual great white, even if you left out the whole part where he'd have probably gotten eaten before crossing the finish line. (But you know ... ratings.) Sharks don't swim in a straight line, and never mind the logistics of trying to put one in an Olympic-sized swimming pool. But viewers were still pissed off, maybe because they were still smarting from the whole megalodon thing.

It's really hard to blame this one on the network — they were pretty open about the fact that this was not going to be an in-the flesh race between actual shark and actual man. There were even pre-show interviews in publications like Vanity Fair that explained exactly how it was going to go down, but that didn't stop half the viewing population from feeling annoyed when they were told in the last three minutes of the one-hour program that the race would be a simulation. Ultimately, this story doesn't say as much about the network's drive for ratings as it does about the fact that most of the viewing population doesn't really pay that much attention to disclaimers or, you know, logic.

Some fun ideas for Shark Week

In 2012, Shark Week's executive producer Brooke Runnette told The Atlantic that producers like to brainstorm new Shark Week content by asking themselves the question: "What would be the most fun?" Some past answers have included meat suits and chum underpants, though Runnette is also quick to promise that those ideas won't ever see the light of anyone's television screen.

Now, of course the real question is why anyone at the network might actually think that meat suits and chum underpants are "fun" ideas. "Fun" is Rob Lowe riding a pair of great white sharks with a mermaid. (Yes, Shark Week really did that, notes Entertainment Tonight, and shockingly, there was no viral outrage when the whole thing turned out to be CGI.) Anyway, Lowe riding sharks is fun. Someone in a meat suit getting torn apart by sharks is not fun. It's simple ethics, Discovery Network.

Shark Week has a cult following

Shark Week might be controversial, but it's not just something that people casually tune into if they're bored on a summer afternoon. Shark Week has cult status, like the "Rocky Horror Picture Show" if Dr. Frank-N-Furter was a great white, and Brad and Janet were a pair of hapless surfers wearing chum underpants. According to Talking Points Memo, in 2010 Stephen Colbert famously declared Shark Week to be "one of the two holiest of holidays" (with the other being the week after Christmas). And on an episode of "30 Rock," Tracy Morgan once gave the sage advice to "Live every week like it's Shark Week."

Fans don't just watch Shark Week, they live Shark Week. Five minutes on Pinterest will give you enough Shark Week party ideas to last until the 2120 installment, and even Martha Stewart is in on the fun, with a whole list of Shark Week ideas including shark cupcakes, shark-inspired outerwear, and a chair made out of stuffed toy sharks. Yes, a chair. Made out of stuffed toy sharks. Still waiting for Stewart to drop a walkthrough for meat suits or chum underpants.