How Long Is The Talmud?

For a non-Jewish person, it would be easy to assume that the Torah (the five books of Moses that lay out God's law for humankind) or even the Tanakh (the collection of holy scriptures — including the Torah — that is roughly equivalent to what many Christians would call the Old Testament) is the most important text in Judaism, especially when one considers how much Christianity (and in particular Protestant denominations) centers the Bible, often to the exclusion of all other texts. However, as Rabbi Pini Dunner explains, while the Torah is "uniquely revered as the essence of [Jews'] faith identity," the central text of Judaism is, without doubt, the Talmud.

According to the Jewish Virtual Library, the Talmud is a series of books that record the Oral Law, commentaries, and instructions by generations of rabbis that codify and systematize the law of the Torah in ways that are often left ambiguous in the text of the Torah itself. Rabbi Dunner explains that the Talmud divides these traditional teachings into two parts: First, the guidelines that help to clarify and codify laws from the Torah that aren't defined in the text itself; and also a series of rules that explain the meaning of bits of Torah that would otherwise be difficult to interpret at face value. With the Torah famously containing 613 individual commandments for the Jewish people, such a thorough and explanatory commentary on every single law would surely be really long. So just how long is the Talmud?

The two Talmuds

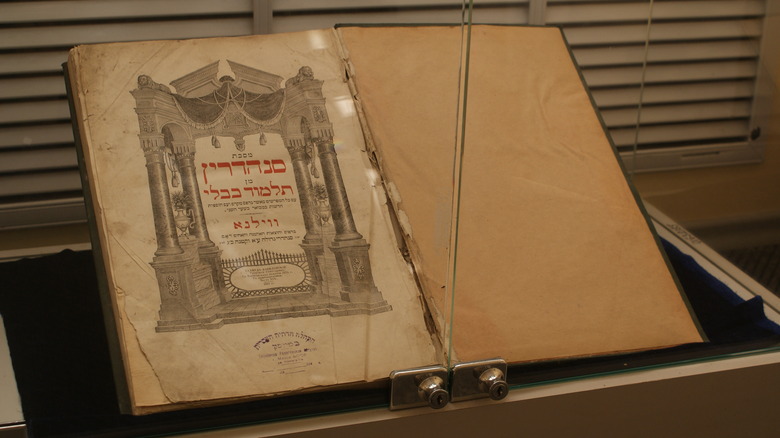

The first thing to understand when pondering the length of the Talmud is the fact that there's not just one but two Talmuds. According to My Jewish Learning, the two texts referred to as the Talmud are the Talmud Bavli (or Babylonian Talmud) and the Talmud Yerushalmi, also known as the Jerusalem (or Palestinian) Talmud. The names derive, as you might expect, from the places where they were put together: the Babylonian Talmud in Babylon (i.e., modern-day Iraq) and the Jerusalem Talmud in ... well, actually northern Israel, not Jerusalem, which might be why some call it the Palestinian Talmud. As Chabad.org explains, the composition of the Talmud began following the destruction of the Temple in Jerusalem by the Romans, which led to a diaspora of the Jewish people and threatened the dissolution of Jewish scholarship. As the generations went on, it became increasingly likely that the teachings of traditional Judaism that had been recorded orally for so long would be lost.

As a result, these oral laws were written and debated in the two centers of Jewish scholarship at the time: Palestine and Babylon. The Jerusalem Talmud was composed first, with the Babylonian Talmud written generations later in the fifth century. Nevertheless, the Babylonian Talmud is the longer and more authoritative text of the two, so normally, when you hear someone say Talmud without any qualifier, they most likely are referring to the Babylonian Talmud. In fact, significant portions of the Jerusalem Talmud have been lost over the years.

Contents and organization

My Jewish Learning explains that both the Babylonian Talmud and the Jerusalem Talmud are made up of two layers: the Mishnah — that is, the compendium of Jewish oral law written down in the first few centuries that make up the earliest layer of the Talmud — and the Gemara, the rabbinic commentaries on that oral law elaborating on the Mishnah. Except for a few variations in wording and order, the Mishnah of the two Talmuds is essentially identical. The Gemara is where the two texts most widely differ.

For this reason, as Chabad.org says, the Talmud — a name which derives from the Hebrew root meaning "learning" — is also sometimes called the Gemara, an Aramaic word that means "completion," implying that the commentaries and discussions of the Gemara complete the teachings of the Mishnah. Likewise, Chabad notes that the Talmud might also be called "Shas," an abbreviation for the Hebrew phrase "shisa sedarim," meaning "six orders." This is because the Mishnah is divided and arranged into six loose orders, or thematic categories, including "agriculture, holidays, marriage and divorce, civil jurisprudence, the Temple sacrifices, [and] ritual purity." Each order is then subdivided into masechtot (tractates), perakim (chapters), and mishnayot (paragraphs). According to the Jewish Virtual Library, the six orders of the Mishnah are divided into 63 tractates arranged by topic. This systematic arrangement makes it much simpler than having to skim all five books of the Torah looking for every law on a specific concept when you can instead just flip to the Sabbath tractate.

Differences in the two Talmuds

As Chabad.org explains, the text of the Mishnah in both versions of the Talmud is written in Hebrew — i.e., the language of the Torah itself — but the Gemara is written in Aramaic, the main language of the Talmudic scholars. But the fact that the two Talmuds were written in different scholarly centers means that the two Gemara are in different dialects of Aramaic. As you might be able to guess, the Jerusalem Talmud is in Palestinian Aramaic, and the Babylonian Talmud is in Babylonian Aramaic. My Jewish Learning says that these two dialects are substantially different, but the languages used in their respective Gemara are not the only differences between the two.

The Gemara of the Jerusalem Talmud includes more long narrative sections than the Babylonian, which tends to favor multi-part conversations and debates between rabbis — a thing which the Jerusalem Talmud mostly avoids. Similarly, the Jerusalem Talmud features a considerable amount of repeated material, which has led some scholars to believe that the editing was never completed on this version of the Talmud. Others argue that the repeated sections are an intentional stylistic choice to help reinforce connections in the minds of the readers. As Chabad points out, the Babylonian Talmud also doesn't feature Gemara on every topic in the Mishnah, as some themes — such as Holy Temple practices — wouldn't apply to Jews outside of Jerusalem following the destruction of the Temple. As a result, the Babylonian Talmud has Gemara on 36 and a half non-consecutive tractates of the Mishnah, while the Jerusalem Talmud covers the first 39 (via My Jewish Learning).

How many pages is the Talmud?

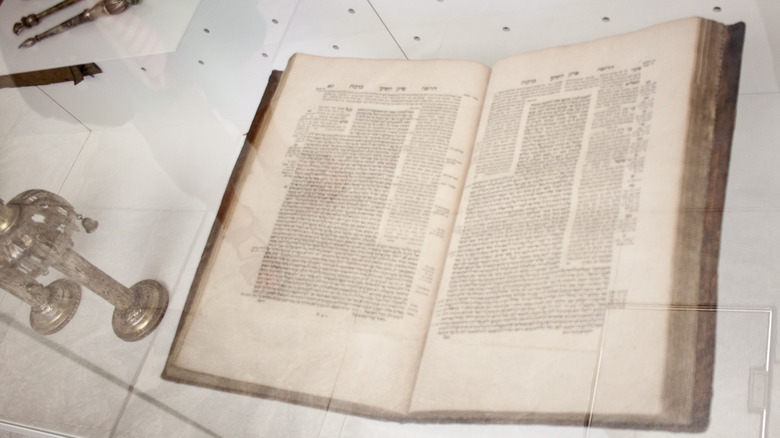

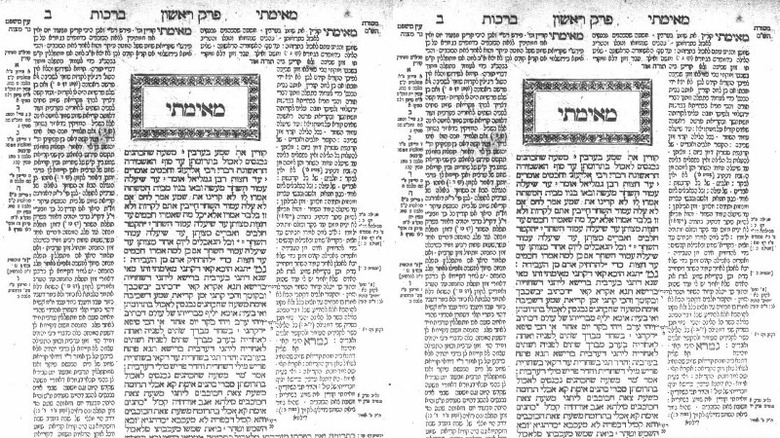

As My Jewish Learning explains, the various cited sections of the Jerusalem Talmud are referred to as "halakhot" ("laws"), and so citations would refer to the tractate, the chapter, and then the individual halakha, similarly to how the Bible is cited with book, chapter, and verse. So a specific law from the Tractate Sukkah, chapter 2, halakha 10, would be referred to as Sukkah 2:10. Alternatively, it may be printed on double-sided pages with two columns on each side, and citations might refer to the page and column (a, b, c, or d). The Babylonian Talmud, however, is typically printed on double-sided pages with one column on each side, so citations would refer then to the page number and side (a or b).

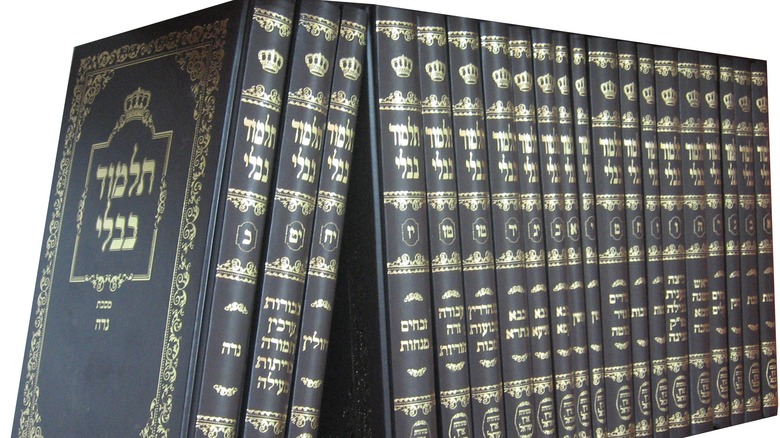

According to Chabad.org, a standard version of the Babylonian Talmud contains a total of 2,711 double-sided pages of text. When a student of the Talmud has completed the reading and study of all 2,711 pages, the following celebration is known as a "siyum hashas" ("completion of the six orders"). However, it is important to understand that study of the Talmud is not considered a one-and-done kind of thing. The Talmud is forever, as you can study the same text over and over again and discover new things each time. The biggest compliment one can give to a scholar of the Talmud is to say they would pass the "pin test," which is to say, if you stuck a pin through the Talmud, they could tell you which word it touched on any specific page.

It's commentaries all the way down

Though the standard Babylonian Talmud clocks in at 2,711 double-sided pages, most editions of the Talmud are going to be longer on account of the commentaries that are typically also included with the Mishnah and Gemara, which total several thousand more pages. As My Jewish Learning explains, most editions of the Jerusalem Talmud feature running commentaries on the text by the 18th-century rabbi Moses ben Simeon Margoliot, also known as the P'nai Moshe. Similarly, the Babylonian Talmud features commentary from the 11th century Rabbi Shlomo ben Yitzchak, better known as Rashi. Many thousands of other commentaries (and commentaries on commentaries) have been composed in the centuries since, including most prominently the Tosafot ("additions") written by descendants and followers of Rashi.

According to Chabad.org, the commentaries are distinguished from the main text of the Talmud through the use of different fonts. The Mishnah and Gemara are printed in a standard block lettering font, while the commentary surrounds and frames the primary text using a more rounded font known as the Rashi script. This layering of text within text within text helps give the pages of the Talmud a unique look.