The Surprisingly Long History Of Bowling Explained

Bowling, or the art of knocking down pins with a heavy ball, is one of the most cherished of American pastimes. Bowler's Journal states that 67 million Americans bowl at least once per year at one of the over 5,000 tenpin bowling centers across the country. For the uninitiated, bowling is a sport in which the player rolls a ball down a long, narrow alley with the objective of knocking down standing pins. Britannica points out that this game is not the same as bowls (or lawn bowling), in which the players roll one ball and try to get it as close to a stationary ball called a jack as possible.

Bowling as we think of it is more related to British skittles, where pub-goers strike down pins with a ball or puck. The most popular form of bowling is tenpin, where you strike down 10 pins. While many people equate tenpin bowling with mid‐20th century Americana, the game itself is far older. How old? Perhaps it goes back to whenever people started chucking rocks to knock down other rocks. Fred Flinstone aficionados may venture to say at least the Paleolithic. But alas, there is no evidence whatsoever that our troglodyte ancestors bowled in bare feet. Still, you may be surprised to learn that our bowling history goes back over five millennia.

Bowling began in Ancient Egypt

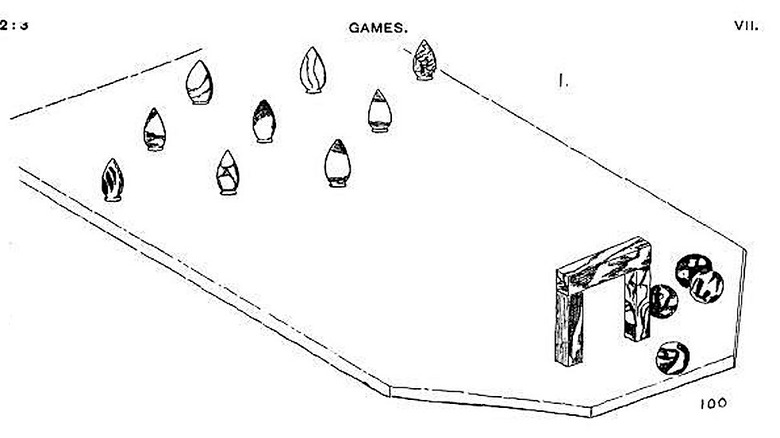

If you wanted to play bowling in a really old-school way, then you should jump in a time machine to go back over 5,000 years to ancient Egypt. Canisius College tells us that by the early 20th century, Sir Flinders Petrie, a British anthropologist, discovered objects in a young person's grave that appeared to be bowling equipment.

It is uncertain if this Egyptian invention influenced later forms of bowling, but ABC Science reports that remains dating to Roman Egypt in the second and third centuries show a room that had a smooth limestone floor and two stone balls. This may have been history's earliest known bowling alley. While it seemed that this was not classic pin bowling, it may have been a related bowling-type sport. More related is the Italian game of bocce, which "Sports Around the World" tells us was played by the Romans as far back as 50 B.C. In any event, these bowling-type games were played by the Romans and Egyptians with leather balls stuffed with corn.

Ancient and Medieval Germans bowled for religious reasons

The first verifiable direct ancestor to modern bowling is in Germany in late antiquity. According to "Sports Around the World," historian William Pehle asserts that in the third and fourth centuries, a religious ceremony was devised called "Bowling for Salvation." Peasants back then carried around a club called a "kegel." This club was very similar in form to today's bowling pins.

In the ceremony, the peasants stood up the kegels as targets. "Modern Sports Around the World" describes how with clerical oversight, participants would roll wooden balls at the kegels. These targets were an allegory for sins, paganism, the devil, and all things bad. They would then roll wooden balls at the kegels as a way to symbolize defeating sin. Those who succeeded in knocking all their sins down were celebrated as sin‐free keglers. Those who did not had to do penance and try again later. It must have been a rather fun way to absolve oneself of trespasses and proved to be very popular.

Martin Luther had a private bowling alley

Germany was the heartland of bowling, and in some ways it became a national sport. For example, Britannica tells us that a major highlight in bowling history was a feast in Frankfurt in 1463, which featured venison followed by bowling. It also was a magnet for gambling in cash or kind. This extended to the countries bordering Germany, such as a 1518 bowling contest held in Breslau, Poland, where the winner was awarded an ox.

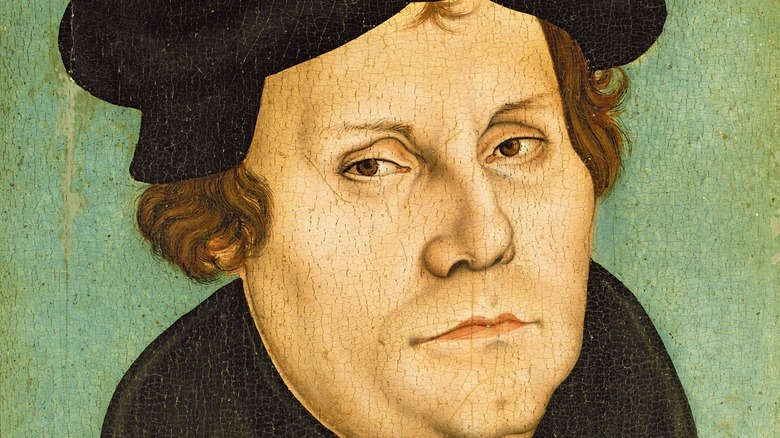

Still, from ancient times straight through the premodern period, the game of kegels was tied up with religion. One of the biggest boosters of bowling was none other than Martin Luther (1483‐1546), the religious leader who sparked the Protestant Reformation. One biography, "Martin Luther," notes that Luther had a single-lane bowling alley installed adjacent to his home in Wittenberg. While traditionally, the pins had represented sins, Luther took them all to represent the Catholic clergy against whom he was rebelling. He took great delight at hurling the ball at the pins.

Utne notes that before Luther, people would bowl with pins numbering from three to 17. Luther is often credited for standardizing the number of pins at nine. Thus, ninepin bowling became the standard form of bowling in Germany and those countries that adopted the sport. In that way, not only did Luther try to reform Christianity, but he also less controversially reformed bowling.

Early bowling bans

As noted, in England, bowls was a popular game which, while only somewhat related to pin bowling, obviously influenced it (and vice versa). According to "Bowling," King Edward III outlawed lawn bowling in 1366 since it drew away his troops from mandatory training. A ban was also implemented by King Henry VIII in 1512. In this case, it only applied to the peasantry since, in the monarch's estimation, they spent too much time bowling and not enough time working (the king himself also enjoyed the game).

England also bequeathed us the concept of bowling in the great indoors. In 1455, a lawn bowling field was covered up, producing, in effect, the first bowling alley. These concepts of bowling as a bit of frivolous sport would migrate to America, where, at least in colonial times, it was the most popular game out there. Bowls, however, would inexorably be supplanted by the popularity of pin bowling since most people must have found it more fun to knock pins down rather than place a ball.

Bowling comes to America

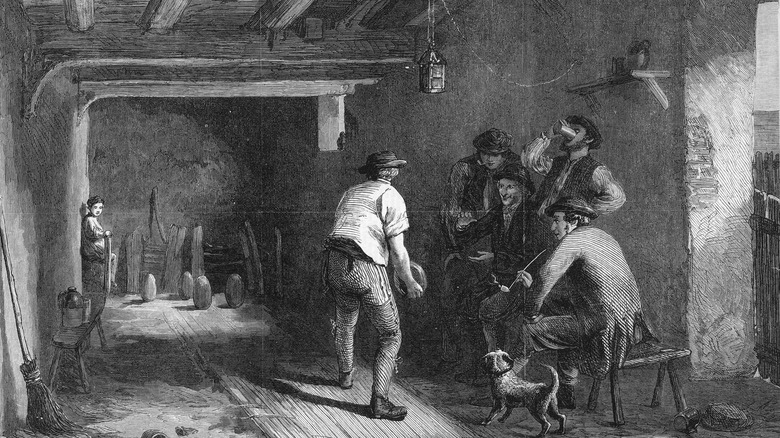

By the time of colonization, pin bowling had spread beyond the borders of Germany. According to Britannica, from the 15th to 17th centuries, bowling slowly spread into the Low Countries. Here, bowlers played inside sheds called "Kegelbahns," which offered lanes made of hardened wood or clay.

The "Historical Dictionary of Bowling" notes that with the Dutch settlement of New Netherland (later New York) in 1624, they brought nine-pin bowling with them. In fact, the oldest park in New York City is named "Bowling Green," although Scientific American notes that lawn bowling occurred there. The Dutch called the spot "the Plain" (per NYC Parks), and it was reportedly the place where Peter Minuit purchased Manhattan from the Native Americans. The Dutch subsequently used it as a marketplace, but they were still associated with ninepin bowling. Washington Irving immortalized it in "Rip Van Winkle" as Dutch ghosts playing the game gave a brew to the main character, which made him sleep for 20 years.

Even though the Dutch were associated with bowling, it was only when the Germans began to immigrate to the United States in large numbers in the 1840s that the game really took off (via "Class in America").

Bowling was banned in the young United States

By 1840, bowling seemed to be an immigrant success story. The "Historical Dictionary of Bowling" notes that it was in that year that the first indoor bowling alley appeared in the United States — Knickerbocker Alleys in New York City. The popularity of the game increased tremendously so that by the end of the decade, there were over 400 bowling alleys in New York alone. Unfortunately for the sport, people liked to wager on the games, and gambling brought crime with it. With it came the scrutinizing eyes of the government, which banned bowling in some localities. One example is Connecticut, which CT Insider reports banned ninepin bowling in 1841. There is a stubborn legend that cheeky bowling entrepreneurs, in order to skirt the law, set down a 10th pin and thus circumvented the ban.

This is likely a historical myth since the Connecticut law specifies that it applies to "more or less than ninepins." Also, there were probably occurrences of tenpins before then. Either way, tenpins soon superseded ninepins in popularity. At the same time, the game was going through growing pains. Some bowling alleys used larger pins and clustered them closer, which produced a ridiculous amount of 300 games (i.e., perfect games). The game lost its fad status, and by the 1860s, it was played mainly by German clubs.

Bowling was standardized in 1895

The "Historical Dictionary of Bowling" tells us that in 1875, 27 bowling clubs formed the National Bowling Association. They attempted to standardize rules, which included regulating ball sizes, foul line placement, and the removal of fallen pins between throws called "deadwood." Other organizations continued this trend toward standardization, including the American Bowling League (formed 1890) and the American Amateur Bowling League (formed 1891). "Sports in American History from Colonial Times to the Twenty-First Century" notes that the American Bowling League eliminated the third throw per frame, allowing a maximum score of 200 points. Incidentally, some variants of three-throws bowling still exist today, such as Duckpin Bowling, which uses smaller pins and smaller balls without finger holes.

The greatest success at standardization came after the establishment of the American Bowling Congress (ABC), which Britannica tells us met in New York City for the first time on September 9, 1895. This group established the rules under which we play bowling today, including setting the weights and dimensions of balls, pin placement, and allowing for a maximum score of 300 by carrying over points from strikes and spares. Bowling began to grow again in popularity. At the same time, the ABC barred nonwhites and women from participating in their organization. Britannica explains how women formed their own separate Women's International Bowling Congress in 1916 and often collaborated with the ABC. Segregation forced nonwhites to form the National Negro Bowling Association (per Ohio History Central).

Modern bowling balls are way different

A major change that came with modern bowling was the ball. "Sports in American History from Colonial Times to the Twenty-First Century" tells us that at the very beginning of the 20th century, players generally used balls made of lignum vitae, a very dense and tough wood. It was certainly easier to drill holes in that than a stone ball. In fact, "Let's Go Bowling" tells us that these wooden balls were prone to tampering. Some bowlers would drill extra holes and fill them with lead in order to produce a sharp curve to the ball (these were called "dodo balls").

Such direct tampering may have changed in 1905 when a dense rubber ball called Evertrue was introduced. Its manufacturer, Brunswick, touted that it was made of an enigmatic substance called mineralite. This had the effect of reducing noise in the lanes. It quickly became popular, and mass production of Evertrue balls began in 1914. Balls have evolved somewhat from this but are still generally synthetic today. According to Chemical and Engineering News, most bowling balls are composed of a powdered metal core mixed with a resin and a lighter outer core containing polyester or glass beads that are mixed with resin. The outer shell is typically made of polyurethane or polyester.

International competitions started in Europe

One of the signs that a sport is becoming serious is the rise of tournaments. Britannica tells us that the first international bowling tournaments may have been held in late 19th century Germany. However, this became much more formalized in 1926 with the formation of the International Bowling Association. This group held several tournaments until 1936.

The heir to the International Bowling Association was the Fédération Internationale des Quilleurs (FIQ), which formed in 1952 and held its first major international amateur competition two years later. In 2014, it renamed itself to World Bowling and in 2020 renamed itself again to the International Bowling Federation (IBF). The American Bowling Congress carried on a tradition of American tournaments that were carried on more regularly than the international ones. The American Bowling Congress eventually merged with the Women's International Bowling Congress and the Young American Bowling Alliance in 2005 to form the United States Bowling Congress.

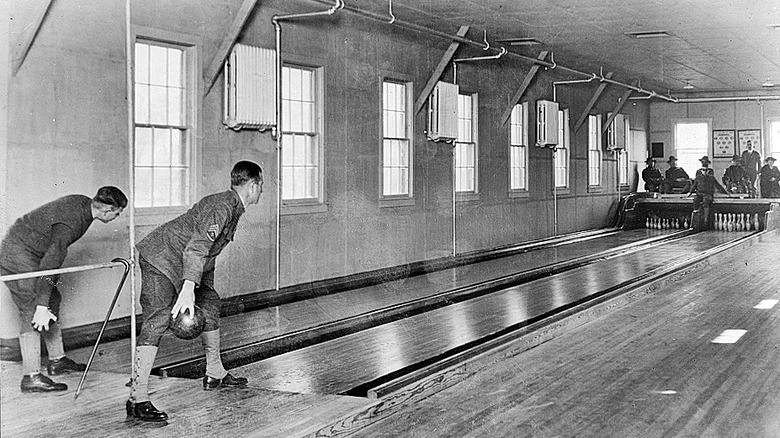

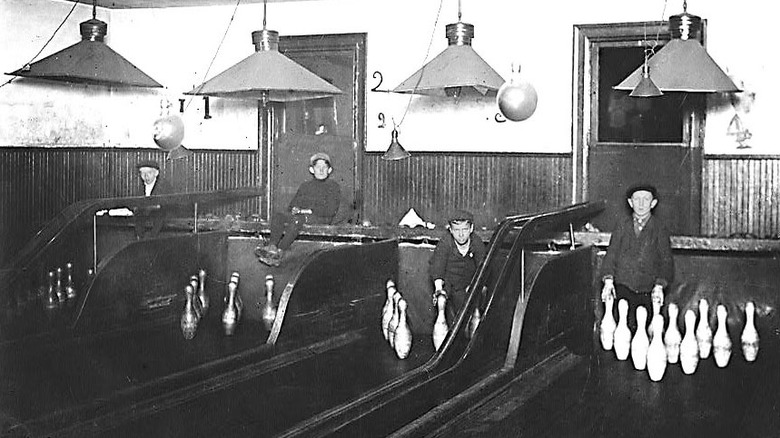

The automatic pinsetter changed the game forever

When you bowl today, you take for granted that there is a machine that will clear off the deadwood and reset the pins. This was not always the case. The Smithsonian Institute reports that prior to automation, boys reset the pins manually. This was a low-wage job that could be dangerous — imagine having projectiles weighing up to 16 pounds constantly hurtling at you. Early attempts to build a machine to do the job were not satisfactory, mainly because the machines could not spot the pins accurately. Then, in 1941, Gottfried "Fred" Schmidt patented one that worked. Not only could the two-ton machine stop the ball with a cushion and reset the pins, but it also returned the ball to the player vis-à-vis gravity. However, the machine wasn't fully ready for general distribution until 1952. By then, Schmidt's patents had come under the control of the American Machine and Foundry Company, which became the primary manufacturer of these pinsetters. The machines quickly caught on so that by 1958, 40,000 of them were being leased.

It should not be underestimated how much automation changed bowling. One local history site, Richland County History, notes that the game increased in tempo and speed. It was often referred to as "Rhythm Bowling." Everything else associated with contemporary bowling — from fancy graphic displays and electric eye foul line sensors to midnight bowling light shows — can be linked to this singular development.

Bowling goes big

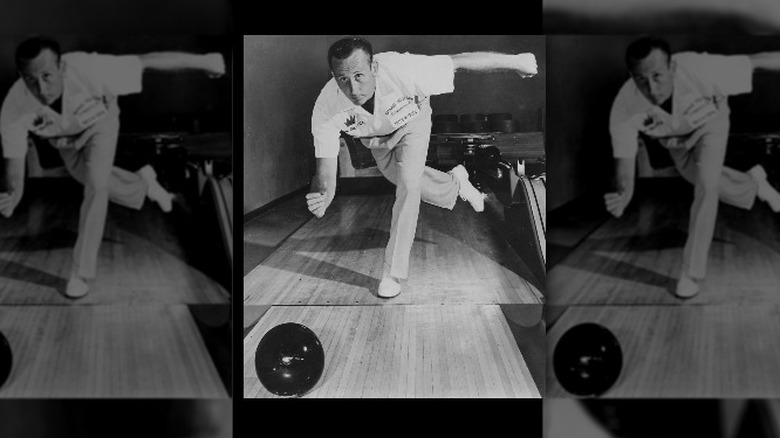

Another watershed moment for bowling was the establishment of the Professional Bowlers Association (PBA) in 1958. According to Britannica, within two decades, bowlers were vying for millions of dollars in prize money. They had a wide media presence and even established bowling pro stars such as Don Carter, a founding member and president of the PBA who took part in televised matches. Carter's history with bowling goes back to boyhood when he worked as a pinsetter in the pre-automation days. In 1964, he was the first athlete in any sport to earn a $1 million endorsement deal — his was with the bowling ball manufacturer Ebonite. Other stars included Dick Weber, who was also a charter member of the PBA, and Earl Anthony, the first bowler to earn over $1 million in career earnings (via PBABowling).

From the 1950s into the 1970s, bowling became a phenomenon in America. Not only were there the PBA tournaments, but the sport also invaded game show media with "Bowling for Dollars," in which contestants from around the country would get three throws at the pins to win cash and prizes.

Bowling became an Asian phenomenon

Bowling had always been international, but this globalism pretty much extended just to America and Europe. However, change was coming. The International Bowling Museum & Hall of Fame explains how after World War II, bowling was introduced by American soldiers to the Japanese. The first civilian bowling center opened in 1952, and by 1967, a professional bowling association had been formed — the Japan Professional Bowler Association.

While Americans dominated the bowling manufacturing business early on, Japanese companies quickly took over. By 1970, there were over 3,500 bowling centers in Japan (via the International Bowling Museum & Hall of Fame). The largest of these was Korakuen Stadium Lanes in Tokyo, which featured 62 lanes. According to Britannica, Professional Bowlers Association players were invited to compete in Japanese tournaments. Uniquely, the dominant Japanese bowlers were women, unlike the patriarchal nature of the sport in America and other countries. Meanwhile, bowling burgeoned in popularity throughout Asia, including in Indonesia, Korea, Hong Kong, Thailand, and Singapore.

Bowling is looking to be an Olympic sport

Bowling had begun to fade in popularity somewhat by the late 1980s, but this did not prevent a push for it to be recognized and incorporated into the Olympics. According to Olympedia, bowling made a foray into the Olympiad as an exhibition sport at the 1988 games in Seoul, South Korea. However, since this one-shot appearance, bowling has failed to be fully accepted by the Olympic community. Certainly, bowling as a physical competition based on skill could certainly qualify. In part, the rejection of bowling has to do with popular conceptions about it.

In 2019, the International Olympic Committee (IOC) rejected bowling's bid for Olympic glory in the 2024 Paris games. An opinion piece in FloBowling.com asserted that this was because, in the view of the IOC, bowling does not appeal to the younger audience it needs. The author claimed that audiences for other popular sports that are part of the Olympics have audiences that are 18 to 49-year-olds, such as basketball. Other less well-known sports — such as skateboarding, surfing, and breakdancing — are examples of accepted sports that naturally appeal to younger audiences.

So is bowling doomed to geriatric oblivion? The answer is not likely. As history has shown, bowling has gone through ebbs and surges in popularity. While it may be accelerated by new and younger stars, it seems that it's only a matter of time before bowling's star will shine bright again.