This Was The IRA's Only Attack On U.S. Soil

The New York City shooting of Irish immigrant Patrick Joseph "Cruxy" O'Connor in 1922 represents the only Irish Republican Army (IRA) attack to occur in the United States. This might come as a surprise, considering the enormous Irish populations in major U.S. cities such as New York and Boston -– and the fact that the attack didn't target British interests but was meant to settle scores with a double agent who had worked for both Great Britain and the IRA.

As The New York Times relates, O'Connor, who got his unique name from his boasts that he would be awarded France's highest military honor, the Croix de Guerre, for his exploits, had grown up in an Ireland that was torn in two by political strife, as Great Britain fought repeated Irish efforts to establish its independence. However, he spied for both sides, earning him the contempt of his Irish compatriots.

O'Connor was pursued all the way across the Atlantic and gunned down near Central Park West by IRA hitmen, in front of scores of passersby. Here is the incredible story of the man who turned coat several times over, and who seemingly never stopped running from his past until the end of his life.

Cruxy O'Connor spied on fellow Irishmen for Great Britain

Despite being born a Catholic in Cork, a hotbed for Irish Republican sentiment during the Irish War of Independence, Patrick "Cruxy" O'Connor's sympathies first lay with the British; accordingly he went to work as a spy for them, reporting on the actions of Irish separatists, reports The New York Times. Ireland had been in tumult for years, with the political situation culminating in the failed Easter Uprising of 1916. The hatred of the British continued unabated amongst many Irish, however, including most of the people with whom O'Connor grew up in Cork, including his neighbor Willie Deasy, who also joined the IRA, states the Irish Examiner.

Although his day job had him working as a bookkeeper for Roches Stores in Cork, The New York Times relates, his secret job moonlighting as a spy for the British overlords who were so hated by most Catholics in Ireland at the time earned him some much-needed cash. The Examiner reports that O'Connor earned £2, 10 shillings every week for his reports on IRA members and activities.

He switched sides, joining the IRA and assassinating a British official

In 1920, Cruxy O'Connor abruptly switched sides, joining the IRA and shooting a suspected government spy for Great Britain -– which he himself had so recently been, the Irish Examiner notes — in his first known killing as a member of the group. The killing of the purported spy was more than a little ironic, as he himself was to change sides multiple times in the revolt against British rule. However, O'Connor appeared to have raised eyebrows from the start, since during military training at Ballyvourney with 60 other IRA members, he asked questions a little too often, later noting the answers in his diary.

As The New York Times relates, the killing put O'Connor in the crosshairs of the British police force, and he went on the lam with his neighbors Willie Deasy and Patrick "Pa" Murray in January of 1921; the men were part of what is known as a "flying column," a highly mobile military group much like guerrillas, who fended for themselves in the countryside between military engagements.

He machine-gunned a British military convoy in 1921

In a February 1921 IRA attack, Cruxy O'Connor used a machine gun in an ambush of a British convoy that was traveling on Macroom-Killarney road near Cork, as related by Paul O'Brien in "Havoc: The Auxiliaries in Ireland's War of Independence." Although several British soldiers, and the commander, Maj. James Seafield Grant, were killed in the fight, O'Connor abruptly stopped firing. The IRA immediately suspected, however, that an informer had tipped off the British to the ambush, telling them it would take place somewhere along their route. Asked later why he stopped shooting his Lewis gun, O'Connor maintained that the weapon had jammed.

Had his weapon really jammed? Or had he just turned coat yet again, feeling sympathy for his former employers? He happened to be arrested by the British soon afterward, finding himself facing execution for the crime of simply carrying a weapon, since the British had imposed martial law in Cork, reports The New York Times. True to form, O'Connor again turned informant, assuring the British police that he was indeed working as a spy for the British government and giving up the names of three IRA members to them. As the Irish Examiner states, O'Connor allegedly had been tortured. According to Jerry Deasy, Willie Deasy's brother, "He was a rather unstable, emotional type and, no doubt, could not take the treatment."

His information led to the killings of six IRA members

The British police force in Ireland, acting on information Cruxy O'Connor gave them, massacred six suspected IRA members -– including O'Connor's own neighbor and IRA compatriot, Willie Deasy — on March 23, 1921, in what became known as the Ballycannon Raid, reports the Irish Examiner.

Deasy and several others had been members of C Company, First Battalion, of the IRA. To this day no one knows why O'Connor informed on his fellow Irishmen, leading to their deaths; some speculate that it was due to the bad blood that had existed for some time between the O'Connor and Deasy families, The New York Times notes. Whatever his motives, the circumstances of the killings were appalling, with the bodies later showing most of the men had been shot from the rear after they had been found asleep and then purposley allowed to escape by the British.

It wasn't long before the IRA discovered the identity of the informant — from sympathizers in the British constabulary, no less — and O'Connor was quickly ushered into protective custody by the British. The six men were laid to rest on Easter Sunday 1921, the fifth anniversary of the bloody Easter Uprising against British rule.

The IRA tried to poison Cruxy O'Connor for being an informant

To punish Cruxy O'Connor for giving up the names of the six IRA members who had been killed in the attack near Ballycannon, Ireland, the IRA came up with an outlandish scheme to poison him, using the food his mother would bring to the barracks where he was being held for his own protection, The New York Times states. The IRA had fellow sympathizer Ethel Condon play the part of his mother, dressing up in clothing like that she was known to wear when delivering meals to her son, and carrying a basket much like the one used in her trips to the barracks. O'Connor's actual mother foiled the poisoning plot, however, by intuiting that her son was in danger and managing to escape from the IRA members who had been sent to keep her home while her impersonator delivered the poisoned food.

Incredibly, the IRA's desperate plot to poison the turncoat was almost successful, however, with Hannah O'Connor reaching the barracks just in time. Condon recalled she had just gotten to the barracks' gate when the real Mrs. O'Connor went inside the building. "If she had arrived a few minutes sooner, it would almost certainly have cost me my life," she stated.

He was sent to live in London, later New York City

In a misguided intention to protect their valued informant, the British first gave Cruxy O'Connor £150 and put him on a boat bound for London so that he could live there in safety, according to the British Official Blue Book (via Britain's Royal Irish Constabulary). However, IRA members Martin Donovan, Daniel Healy, and Liam O'Callaghan came close to ferreting him out in London in the summer of 1921, losing track of him at the last moment, the Friends of Sinn Fein state.

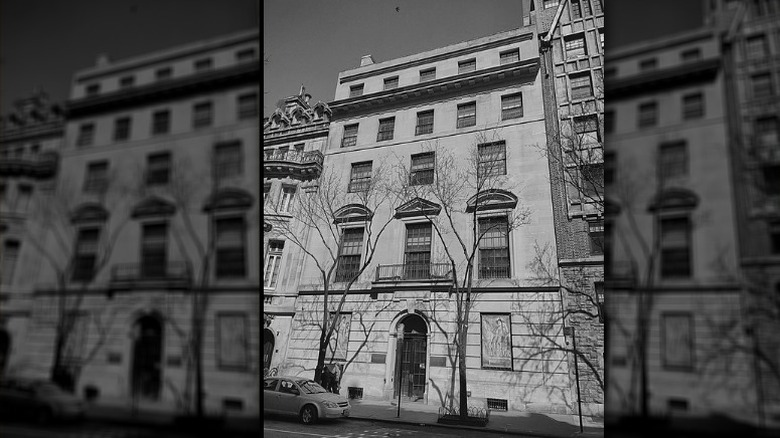

After realizing the IRA was already hot on his trail, British authorities then shipped their informant to New York City — perhaps not realizing that the presence of many thousands of Irish immigrants in the city actually placed him in great danger of retribution there, almost the same as if he had been on his home turf. The Friends records that before long, a woman known only as a "Miss Conway," according to Healy's statement on the attack (via the Bureau of Military History), reported to the IRA that O'Connor had been seen in New York. His family was indeed now living at 483 Columbus Avenue in Manhattan, notes The New York Times, after having been exiled from Cork after their son's double-dealings, per the Irish Examiner.

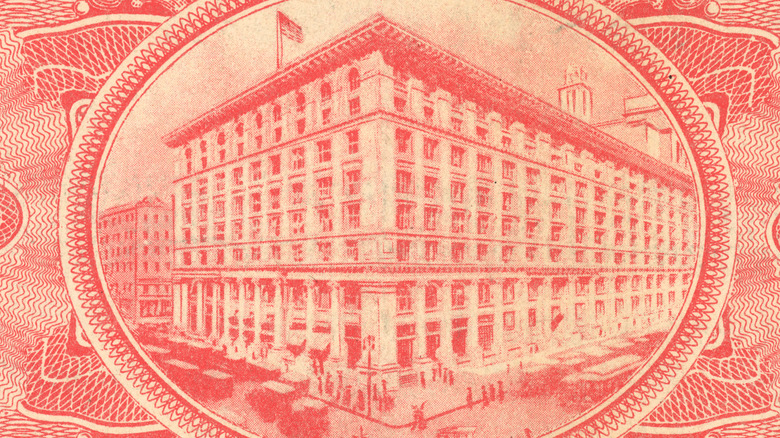

He went to work at a Manhattan department store

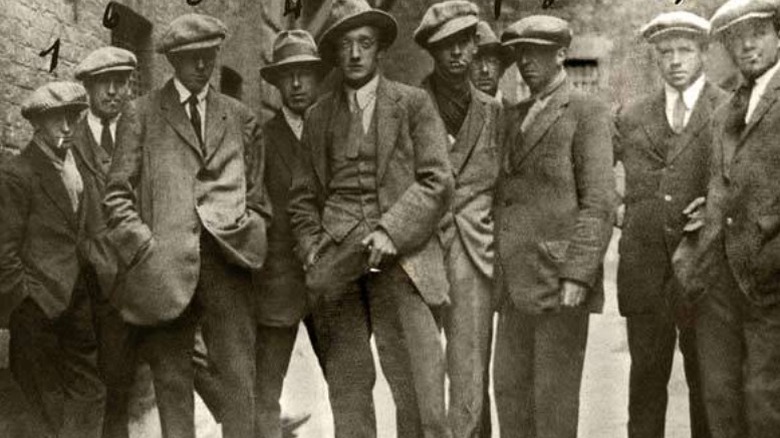

Cruxy O'Connor found work as a department store bookkeeper at B. Altman's on 34th Street in Manhattan, after British authorities sent him to the U.S. However, it wasn't long before the despised double agent was located and targeted by the IRA in the tightly knit Irish world of New York City, according to The New York Times. IRA gunmen Martin Donovan, Patrick "Pa" Murray, and Danny Healy arrived in the city in early 1922 in hot pursuit of the man who they blamed for the deaths of six of their compatriots in Ballycannon, less than one year before. They sailed separately, according to The Friends of Sinn Fein, in order to avoid detection, with Healy traveling under an assumed name on a passport he received in London. According to the Bureau of Military History, Healy stated Murray received his passport through bribing a London official, and Donovan sailed to New York as a stowaway.

New York City union chief Jimmy McGee armed the men after their arrival, giving them revolvers, The New York Times notes, adding that O'Connor's innate espionage instincts immediately kicked in, and he quickly realized he was in their crosshairs. He quit B. Altman's after he noticed them outside the store.

IRA hitmen shot him on the anniversary of the Ballycannon massacre

The New York Times explains that the only IRA attack on U.S. soil didn't occur on any random date; it was meant for Easter week, one year after the massacre in Ballycannon that killed six of its members. The hitmen were in a car that followed Cruxy O'Connor for some time, in an effort to reach him when he crossed the 83rd Street entrance to Central Park.

The three hitmen from Cork came upon O'Connor as he was walking down Columbus Avenue. Incredibly, a detailed account of the shooting later given by Danny Healy is part of an extraordinary statement preserved at Ireland's Bureau of Military History. One eyewitness told The New York Times that the man who shot O'Connor said to him "I've got you now" just before he opened fire. Notably, Healy's own statement was redacted and doesn't include his participation in the actual shooting of O'Connor. Somehow Healy was able to flee the scene despite initially being pursued by a number of witnesses, getting away on a subway train, The New York Times notes.

O'Connor's parents and family, who lived on Columbus Avenue, told the press only they had no comment and would give no information on the case other than acknowledging that O'Connor had been a member of the IRA and had fled the country after receiving death threats.

Cruxy O'Connor survived his wounds

Despite having been shot four times by the three IRA hitmen who had tracked him for months, Cruxy O'Connor somehow survived his wounds to the jaw, back, stomach and side, according to The New York Times. He ended up on the steps of the Semple School for Girls eyewitnesses who had seen the shooting firsthand lifted him up off the street. O'Connor was then take to a local hospital, as per a 1922 article in The New York Times.

Refusing to name the gunman to the New York policemen who arrived on the scene, O'Connor just seemingly wanted to make it all go away. IRA hitman "Pa" Murray stated in an interview he gave in the 1960s (via The New York Times), "I was sorry after," indicating he was aware O'Connor had previously been tortured after he was picked up by the authorities after assassinating a British commander in an ambush.

The IRA hitmen escaped authorities and returned to Ireland

The saga of the only IRA attack in the U.S. continued on its almost unbelievable trajectory, as the hitmen who shot Cruxy O'Connor in broad daylight escaped arrest after union chief Jimmy McGee put them aboard steamers bound for Ireland, as related by The New York Times. Two traveled as stowaways, and the third simply sailed back home under a false name. It was none other than McGee, known as a "fixer" of the New York waterfront, who had initially given the men their weapons and had earlier that year attempted to transport of 500 Thompson "tommy" submachine guns from New York to Ireland.

The hitmen traveled on a steamer to Hamburg, Germany, signing on as firemen, of which such ships had a great number, according to Healy's later statement (via the Bureau of Military History). The firemen would work in three shifts, he added, giving them extra anonymity, which he needed because he knew that the U.S. authorities knew his real name. After arriving, the men found passage to London as stowaways, with part of their journey spent in the ship's coal hole; they soon arrived in Paddington Station and, Healy related in the statement, "arrived safely in Cork on the last Sunday in May in 1922."

Cruxy O'Connor made a new life in Canada and the U.S.

According to Irish Central, the shooting of Cruxy O'Connor was ordered by IRA intelligence chief Michael Collins, noting that the only IRA attack on American soil was with the full knowledge and approval of Collins, who, at the time, was working on the Anglo-Irish Treaty in late 1921.

Despite later Irish claims to the contrary, O'Connor survived, thanks to the expert work of a surgeon, according to Gerard Murphy, the author of "The Year of Disappearances: Political Killings in Cork 1921-1922." Incredibly, the three hitmen bragged to their Irish supporters after returning home that they had killed O'Connor; given the extraordinary wounds he had sustained, it was easily believed. "The story went into local lore as one of the legends of the revolution," Murphy relates.

As The New York Times states, O'Connor actually emigrated to Canada, later moving back to New York, then to England. He ended up passing away in Canada in 1952 at 60 years of age, according to the Irish Examiner. Since the Irish went on to win their independence from Great Britain, it's understandable that they wanted to believe that the hated traitor was punished for his sins. Going down in history as "the Benedict Arnold of Cork," The New York Times notes, a song about him says "But curse that Cruxy Connors, that treacherous turncoat and spy/Who sold away on that fateful day the Ballycannon Boys."