What Did Ancient Egyptians Believe About Ghosts?

Ghosts have always been with us. They may seem to be denizens of modern horror movies and ghost-hunting reality TV now, but stories of phantoms date back thousands of years. In fact, what may be the oldest image of a ghost is well over 3,000 years old. According to Smithsonian Magazine, it was found on a Sumerian clay tablet that dates back to 1500 BCE. Ghosts were part of Mesopotamian belief for quite a long while, but they definitely weren't the only ancients who believed that the dead could return.

While people over in Babylon and Sumer were dealing with spirits, the ancient Egyptians were wrangling with ghosts of their own. For much of the very long history of the kingdom, many Egyptians believed that the border between the worlds of the living and the dead wasn't a hard and fast thing. Indeed, it was so permeable that not only could ghosts appear to the living, but they could be pestered with requests for spectral favors (or pleas to stop their vengeful acts).

According to the World History Encyclopedia, some of the aspects of ancient Egyptian ghosts could seem very familiar even thousands of years later. A ghost appears to a man asking for help in restoring respect to his final resting place. An angry wife returns from the grave. Priests are brought in to manage some troublesome spirits. But there's much more to it all than haunted houses. Here's what the ancient Egyptians believed about ghosts.

Ghosts were part of the natural order

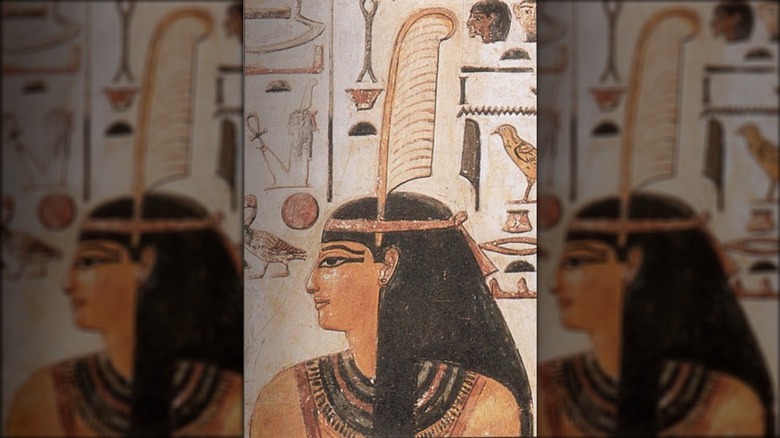

Ancient Egyptians lived in a world that was highly ordered from life to the afterlife. That order was all-encompassing, shaping everything in existence regardless of whether or not a person was in the land of the living or that of the dead. As part of a cosmology based on ma'at, or order, everything had its rightful place, including ghosts. Therefore, many accepted that spirits were a part of their reality, even if they went largely unseen. That said, it was generally understood that the dead would keep to the afterlife, maintaining the balance and cosmic harmony that the true fulfillment of ma'at required. According to ThoughtCo, ma'at was interpreted both as a concept and as a goddess wearing the symbolic "feather of truth" on her head.

Of course, there's the ideal, and then there's reality. Occasions when crossover happened typically meant that someone had to put in the work to restore order. According to the World History Encyclopedia, any mingling of the living and the dead beyond sanctioned rituals like prayers and offerings was usually a pretty clear sign that something had gone wrong. Perhaps someone was buried incorrectly or had been forgotten entirely, leading to a sad or even angry ghost. Maybe a living relation of the spirit hadn't been conducting themselves properly, and someone had to enact a ghostly reminder for them to straighten up. Whatever had gone awry, it was usually up to the living to set things right.

Egyptians had evolving beliefs about the soul

Originally, as the World History Encyclopedia explains, Egyptians thought of the soul as a single entity. Called the khu, it was everything of a person that would survive death and journey to the afterlife.

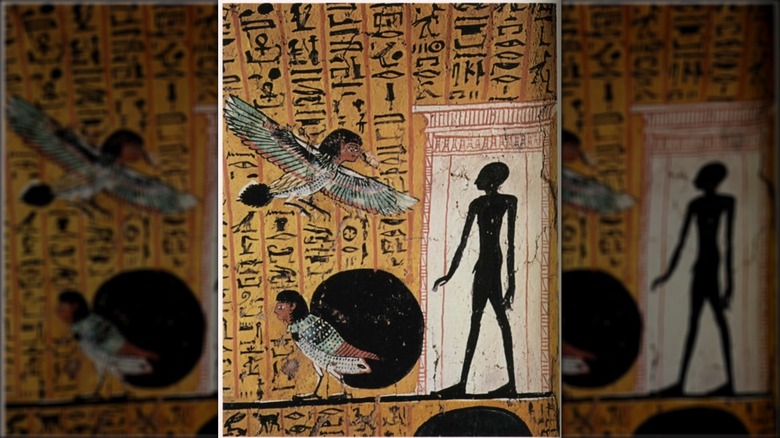

However, "ancient Egypt" is a term that covers millennia of history and many different people. You can hardly expect everyone to buy into the same exact religious beliefs over thousands of years. When it came to spirits, the initial understanding of the human soul as a single entity turned into one that involved as many as nine different components. These generally included the ka, a kind of spirit that was an individual's personality; the human-headed, bird-bodied ba that could travel between realms; the shuyet, or shadow form; and the akh, the immortal part of a person that sometimes also stood for the ghostly whole. According to "Religion and Magic in Ancient Egypt," the akh was often the aspect that was responsible for getting involved in the affairs of the living.

For the intangible aspects of a person to find their way to and from the spirit world safely, they still needed a physical body to recognize. Mummification, which many hoped would preserve the khat (body) in perpetuity, was the answer, per the World History Encyclopedia. But if a dead person's family didn't max out their budget on the best embalming and burial service available, then their loved one's spirit could return to give them grief for being cheap.

Many Egyptians believed that ghosts lived like they had while alive

Though beliefs about the afterlife and human spirits varied throughout ancient Egyptian history, a few common themes persisted through the centuries. One was that the deceased would need to be buried with an array of goods, which they would take with them to the afterlife. According to "Religion and Magic in Ancient Egypt," this included a regular supply of food offerings left at the deceased's tomb to sustain their spirit form. Only, as time went on and more and more people died, going around to all the tombs and leaving vittles for the family ghosts would have been a serious burden. Some paid dedicated priests to take on the full-time job, while others used magically-charged inscriptions to supply their dead loved ones with food for all eternity.

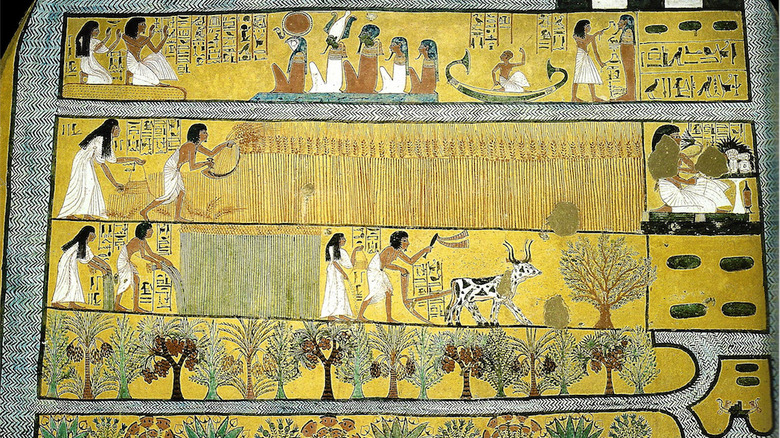

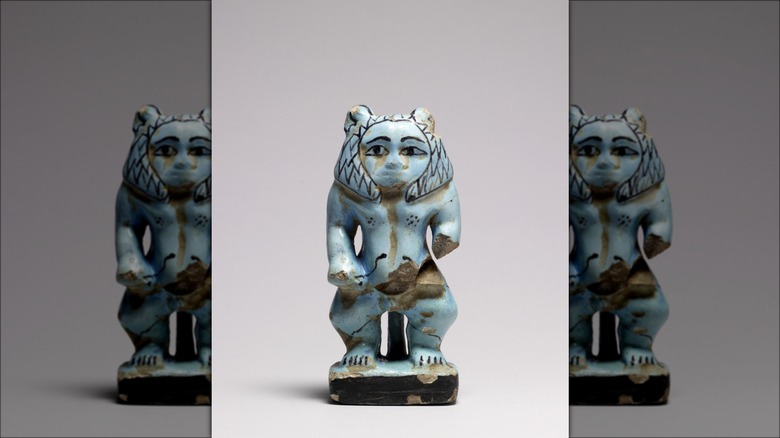

Food and grave goods were prosaic enough, but then there was the matter of labor. People expected that they would have to work in the afterlife much as they did in real life, completing tasks like harvesting grain. In later periods, the solution was to bury the dead with small human figurines, often called shabtis, which would spring to life in the next world and do all the chores (via World History Encyclopedia).

Charming as these mini ghost servants-to-be may appear to modern observers, the earlier version of this practice was far darker. According to the American Society for Overseas Research, the earliest pharaohs were accompanied to the grave by human sacrifices.

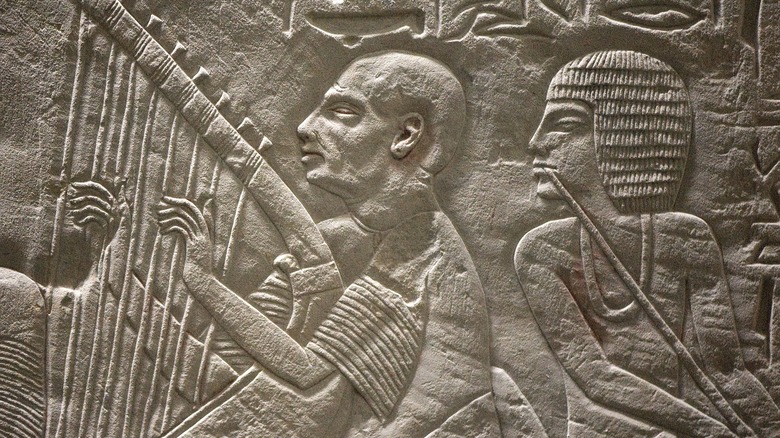

Later beliefs made the Egyptian afterlife a potentially scary place

While some of the earlier texts and inscriptions for ancient Egypt make it seem like everyone was pretty invested in an orthodox view of the afterlife, things got complicated as the centuries went on. According to the World History Encyclopedia, some accounts from the Middle Kingdom onward cast doubt on earlier notions of a blissfully happy paradise. The text of one harpist's song exhorts listeners to live their lives to the fullest extent. After all, the harpist sang, the only guarantee is death; we can hardly be certain what happens after that. The song even casts doubt on the existence of human spirits, given that it argues no one has ever returned from an afterlife to give their incontrovertible report.

This change in attitude left room for alarming questions. Could spirits who weren't properly attended to suffer forever? What did it mean to exist as a forgotten and unloved spirit? At any rate, the existence of ghosts seemed to have played into this doubtful attitude. After all, if everyone was supposed to be relaxing in a blissful afterlife for all eternity, then what would any of them return as ghosts? It clearly sent a chill down some ancient person's spine. As one man in the skeptical Middle Kingdom told a ghost, it seemed to him that the unfortunate soul was trapped in a gloomy, static afterlife. "Darkness is in your sight each day," he said (via World History Encyclopedia).

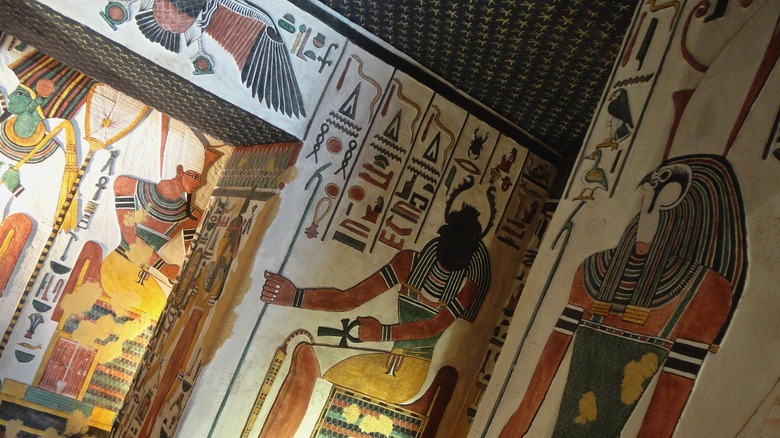

Tombs were linked to spirits

As ancient Egyptians began to doubt the idea that everyone went off to a pleasant afterlife, some began to believe that ghosts hung around in the earthly realm. But where would they be most likely to be found?

Tombs became increasingly linked to ghosts and their welfare in the afterlife. One story from the New Kingdom period (1570 – 1069 BCE) concerns the ghost of Nebusmekh, who approaches a passing priest, Khonsemhab. He complains that his tomb has become a forgotten ruin, and so he can't rest. Khonsemhab orders the construction of a new tomb for the dead man, and, though the rest of the story is lost, it's reasonable to guess that Nebusmekh is placated by the new digs and the attention paid to him(via World History Encyclopedia).

These more or less final resting places could sometimes come with ominous warnings for robbers disturbing spirits' territory. As National Museums Scotland points out, these weren't really "curses," but more warnings that ill effects would naturally follow anyone who was foolish or greedy enough to rob the dead. Things were more akin to a warning to keep out than a guarantee that an angry ghost would tail an unwary thief.

Vengeful ghosts could cause trouble for the living

While some ghosts appeared to the living to ask for help or just to mope around, other returned spirits had a more fiery disposition. At least, that's how the ancient Egyptians saw things, sometimes to the point where they blamed real-world misfortunes on the activities of an unseen but still very angry ghost.

Take one man, an unfortunate who lived around the Middle Kingdom's 20th dynasty. Though we don't know much about his situation, it's clear that things have been rough. As quoted in "The Attitude of the Ancient Egyptians to Death and the Dead," he plaintively asks, "What wicked thing have I done to thee?" He then goes on to claim that he was a loving, loyal husband during her lifetime, never once "entering into a strange house." When she had died, he grieved appropriately and buried her in fine linen. He even avoided those naughty "houses" for years, "though it is not right that one like me should have to do it." It's unclear what, exactly, the man thinks his ghostly wife has done, but it was clearly a serious state of affairs.

Another widower actually wrote a letter to his wife's coffin. As Archaeology reports, the husband, Butehamun, asked his wife Ikhtay's coffin to put in a good word for him with Ikhtay herself. Butehamun's problems aren't specified, but it's clear that he thinks his deceased wife may be the cause, perhaps because he remarried after her death.

It could take a lot of effort to fix a ghost problem

So, an ancient Egyptian determined that their problems stemmed from a ghost. Then what did beleaguered folks actually do when faced with a spirit problem? According to the BBC, they might do what many horror movie characters have done in years since: find a priest. Of course, Catholicism being quite a ways off from its debut, they wouldn't have been talking to an ancient Father Merrin. Instead, they could have turned to a polytheistic priest or perhaps a local wise woman who knew about these sorts of things.

Like the priests of "The Exorcist," ancient Egyptian ghostbusters would likely have made quite a ruckus, at least if all they wanted to do was to get rid of a ghost. Shooing away a spirit could involve shouting, stomping, and the energetic use of drums or other percussion instruments. While the BBC doesn't make it clear that these priests were paid for their services, it seems fair to assume that they were. After all, the ka priests of other eras, tasked with maintaining the offerings at a family's collection of tombs, were effectively employees of that family.

Priests could be there at the start of a ghost's spiritual existence, too, given that embalmers were also priests of a sort who could command a pretty penny for their services. A skillful and well-paid embalming priest would hopefully keep potential ghosts happy in the first place (via World History Encyclopedia).

Ghosts went on a perilous journey to the afterlife

One of the prevailing ancient Egyptian beliefs throughout history was that spirits had some serious work ahead of them right after death. There was no magical teleportation to the world of the dead. Instead, as History Extra notes, it was a journey that demanded knowledge of various spells and phrases to safely pass through a series of gates. If the dead person was lucky, they had a well-off family who would bury them with the text of all these incantations and passwords, now commonly known as the Book of the Dead.

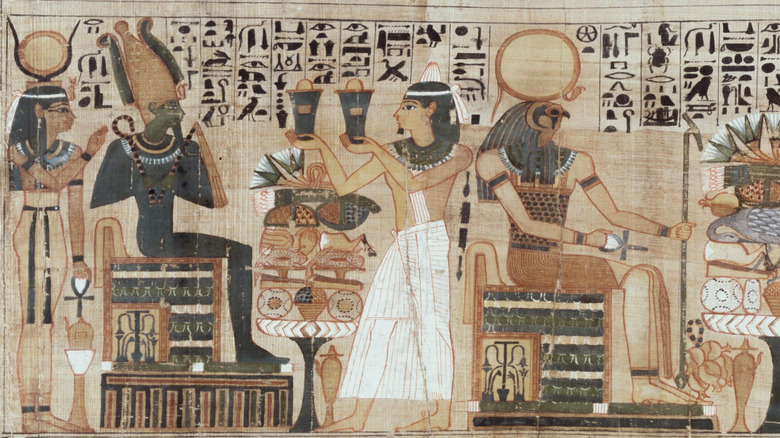

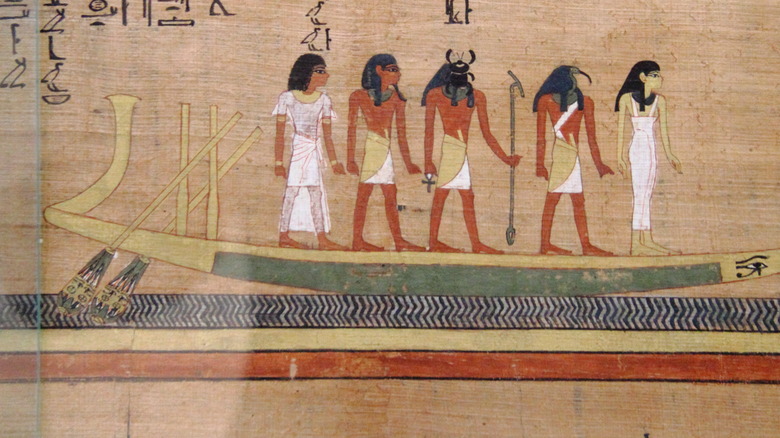

The spirit hopefully got it all right, as the penultimate step of the journey was to sit before the gods and be judged. The god Anubis would take the dead person's heart and weight it against the concept of truth or justice, often represented by a feather. If the organ outweighed the feather, the heart would be tossed to a fearsome crocodile-headed deity, and the dead would vanish.

If the ghost of a person made it past this terrifying challenge, then they might join the sun god Ra as he ferried the boat of the sun back and forth (via History Extra). Or they might snag a spot in the Field of Reeds, which was essentially just like life in Egypt, only much better. According to the World History Encyclopedia, all the crops in this paradise were ridiculously abundant, everyone was gorgeous, and no one wanted for anything ever again.

Ancient Egyptian ghosts also had to deal with demons

Perhaps some ancient Egyptian ghosts returned not because of a rundown tomb or troublesome family member, but because the other denizens of the afterlife were seriously spooky. According to Archaeology, many ancient Egyptian people believed not only in the gods and the spirits of humans but in a vast array of minor beings as well. These small spirits may have made more of an impression on an Egyptian's everyday life, given the number of small figurines and household shrines that paid homage to them. Perhaps calling upon minor deities or even less major spirits made things seem more possible than if someone supplicated a major, but distant god.

Researchers today might call them "demons," but that doesn't mean they fit into a monotheistic cosmology of good and evil. Like aspects of the human spirit, they were able to move between worlds and could interact with still-living humans. They were complex, too, taking on many different forms and working for many different purposes.

As Archaeology argues, the most surprising thing to modern people is the realization that the demons of ancient Egypt were very close to home. That's because the ghosts of the dead could be understood as part of this semi-divine group, either wreaking havoc or helping the living out, as the forces of cosmic justice demanded. A regular, old human, upon their death, could become a spirit that would then gain power and be paid tribute to by their descendants.

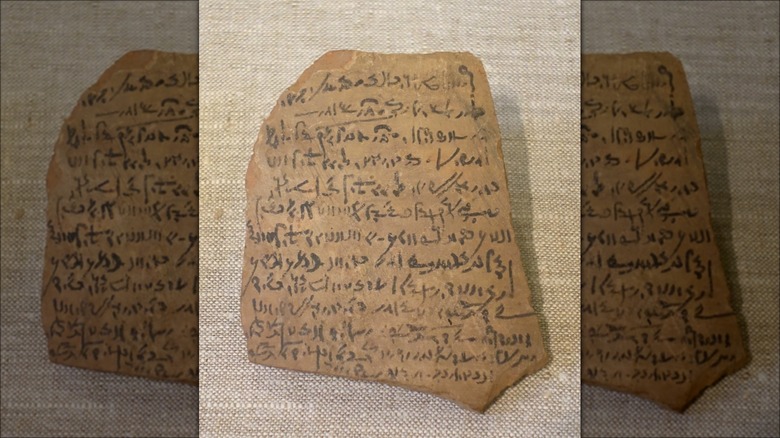

Ghosts might receive letters

Though there are certainly stories of ghosts making contact with the living through means like simply appearing before a person, that certainly wasn't the only way living folks could contact their dead counterparts. As University College London notes, there are plenty of examples of letters to the dead. Living relatives of the deceased could petition their incorporeal loved one for all sorts of favors. It may have gotten annoying for anyone who was in high demand, but they could at least have taken comfort in knowing that all of those letter writers assumed they were a pretty powerful spirit.

If they were receiving the missives, anyway, that meant that they had proven themselves to be worthy of a good afterlife and potentially could present a case before some seriously powerful gods (via World History Encyclopedia). Some of the messages were written on papyrus, but others would have a request inscribed on a pottery bowl that was then placed alongside the offerings in a tomb chapel.

And what were these ghosts called on to help resolve? Letters to the dead span just about all of ancient Egyptian history, according to the World History Encyclopedia. Over those thousands of years, the general form included a little small talk first. Then, the letter writer got to the request, which could deal with someone's health, hopes for the birth of a child (usually a boy), or lending a ghostly hand in a legal matter.