How The Sewing Machine Changed History Forever

It's always difficult to peer into the future and predict how a specific invention or idea will change things. Often new products are created to solve specific, narrow problems, with no idea that they might have a far-reaching impact that actually changes the direction of society as a whole. And it often takes decades for the connection between a new invention and a transformed society to be made clear.

That's the case with one of the greatest inventions in American history: The sewing machine. Still a staple of clothing manufacturing today, as the encyclopedia Britannica points out, the modern sewing machine may have a lot of bells and whistles like touchscreens and a menu of stitches. Still, its basic operation is surprisingly unchanged from its initial burst of popularity in the mid-1800s. You can still find them in schools, factories, and the studios of fashion designers — even if you've never sewn a stitch in your life, you're probably familiar with the iconic look and operation of a sewing machine.

And while the automation of a laborious, repetitive task like sewing seems like an obvious benefit, the impact of the sewing machine goes far beyond that. Once the first workable design hit the market, life would never be the same. Here's how the sewing machine changed history forever.

It revolutionized clothes making

As reported by BBC News, people had been trying to invent the sewing machine for decades. Everyone knew that making clothing was time-consuming, laborious, and expensive. Which meant that everyone knew there was an economic opportunity in figuring out how to automate the process. Up until the mid-1800s, almost all clothing around the world was made by hand — Literary Hub notes that in 1811 two-thirds of all the clothing worn in the U.S. was homemade, and the only "off the rack" clothes were cheap items sold at "slop shops."

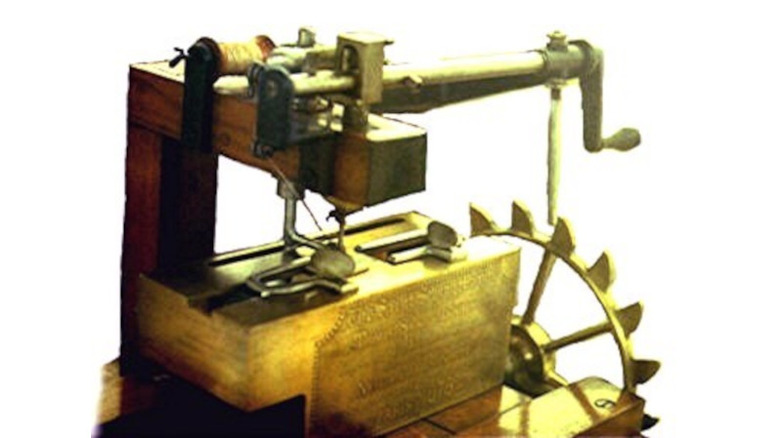

This wasn't news. According to Smithsonian Magazine, the first design for a sewing machine was produced in the late 1700s by a man named Thomas Saint, but it was never manufactured. Over the next several decades, there were many more designs as inventors of all stripes tried to solve the problem, but most of these simply did not work very well. Some were too complicated — like a version that attempted to mimic the graceful hand movements of the inventor's wife. Others actually sparked angry reactions from tailors who felt their livelihoods threatened, leading to destroyed machines.

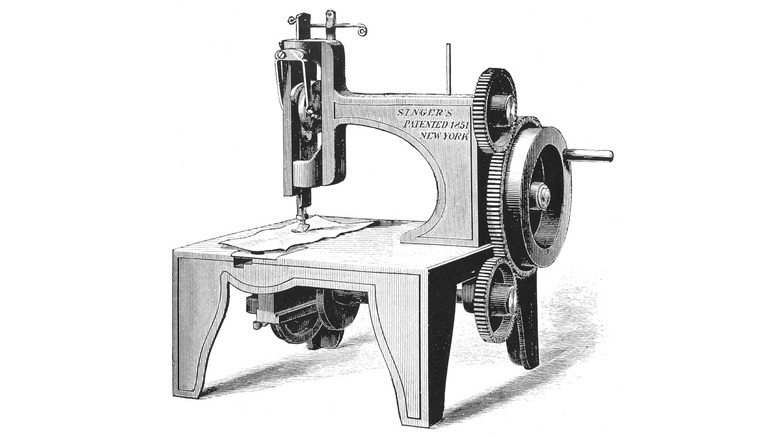

When Isaac Merritt Singer came across a sewing machine designed by inventor Elias Howe, he was challenged to improve the design. He immediately saw how to change it in order to be reliable and effective — and the first reliably working sewing machine was soon on the market.

The sewing machine sped the process up

Making clothing by hand is a slow and meticulous process. According to History Today, it required more than 20,000 stitches to make the average shirt in 1867. A "competent" seamstress could usually manage about 35 stitches a minute, which means it took a minimum of 10 hours to make one shirt, and might have taken as long as 14 hours — for a single shirt. This was the same whether you were a seamstress sewing clothes for money, or a member of a household (almost always a woman) making or repairing clothes for your family. A single outfit could take a week to produce.

When Isaac Singer introduced his sewing machine design in 1851, however, it changed everything. Its main advantage was speed: It was capable of producing 3,000 stitches in one minute, which reduced the time required to make one average shirt from 14 hours to just one hour, according to BBC News. This didn't just mean that more shirts could be produced in a day than ever before. Those 3,000 stitches represented the work of about 10 seamstresses, so you could do the math differently: Instead of having several seamstresses working to produce clothing, you could have just one working with a machine.

It gave hope to the oppressed

Like many inventions, the introduction of a reliable sewing machine prompted many to hope that it would change lives for the better. Whose lives? Women's lives, mainly.

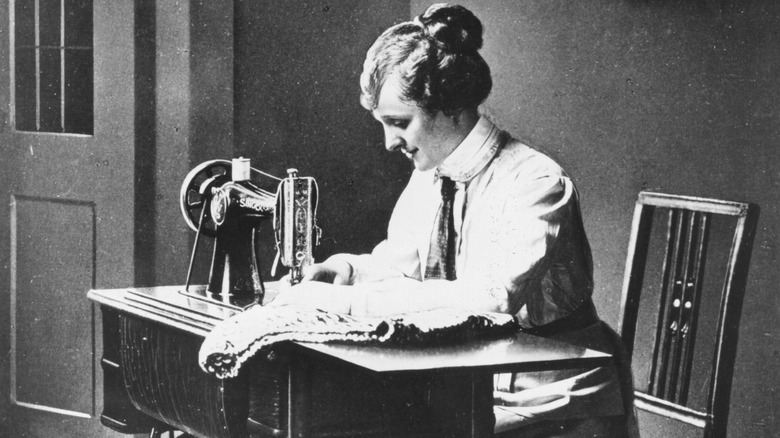

As noted by BBC News, in the middle of the 19th century, when the sewing machine first made a splash, women were considered second-class citizens in many ways. They lacked the ability to vote and were usually excluded from most professions, purely due to misogyny and prejudice. There were, in other words, few jobs that were deemed suitable for a woman to do. But according to historian Amy Boyce Osaki, sewing was considered a "truly feminine employment." Women were generally expected to know how to sew, no matter their class or station in life. History Today notes that earning a living with "needlework" was considered respectable enough for a woman, and most seamstresses in the 19th century were women — and their lives were miserable. Working conditions were awful, the pay was low, and it took so long to make a single garment (14 hours for one shirt, for example) that their work ate up all their time.

As a result, there was hope that the sewing machine would free these women to some extent by making their work easier. Instead of laboring all day long to keep up with clothing orders, they could work at a more leisurely pace — and earn more with higher production.

It inspired the first payment plan

The effects of the sewing machine go beyond fashion. The first working designs actually led to the invention of a common shopping practice — the payment plan.

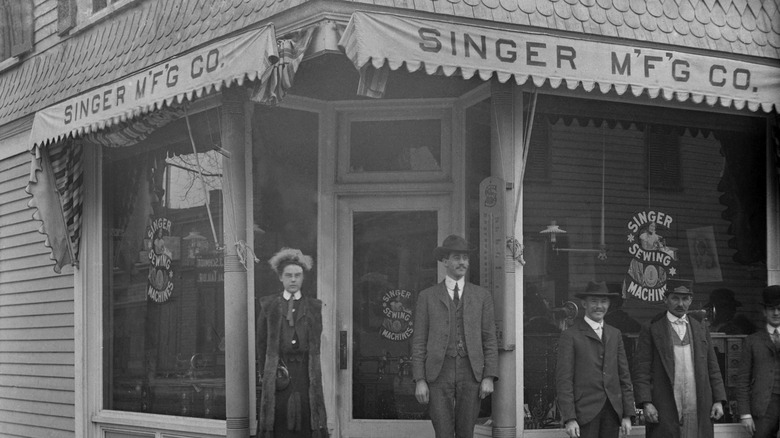

When Isaac Singer began selling his sewing machine, it was quite expensive. According to Time, the machines retailed for $125 at a time when the average income in America was just $500. Nevertheless, the machines were still incredibly popular and sold well despite their cost, but they were out of reach for most middle-class families. And BBC News notes that previous versions of sewing machines had been incredibly unreliable, earning the device a reputation as a waste of time and making people hesitate to buy one.

As reported by History Today, the Singer company, sensing an opportunity, came up with a creative idea: They sold the machines to people with good credit for just $5 down. The customer then paid off the machine in installments of $3 to $5 until the purchase price, plus interest, was paid off. It was the first-ever payment plan in American history. Singer backed up these sales with home visits to help set up the contraption, and follow-up calls to ensure things were going smoothly — both strategies to make sure people didn't give up on the machines and return them. The payment plan strategy worked very well for Singer, which grew into a company earning $22 million a year by 1875.

It promised women financial independence

As noted by The British Library, while sewing had traditionally been considered a women's job and was one of the few areas where a woman could work, the 1840s saw a sharp rise in the number of women engaged in needlework. According to the Mill Museum, in 1850 there were 5,000 women sewing shirts in New York City alone, and most of them earned less than $400 a year (about $15,000 when adjusted for inflation). Most of these women took on the work in order to support themselves or supplement the income of their families. History Today notes that many of these women were actually born into "respectable" families, but were forced to find employment when their family's fortunes declined, and needlework was one of the few professions such women could take on without shame.

The sewing machine sparked a change in the way women were regarded — and marketed to. According to BBC News, the Singer company knew their machines were expensive (they sold for about $125 when first introduced), so their marketing stressed the return on that investment, claiming that a "good female operator" could earn $1,000 a year, or more than twice what a typical seamstress earned. This seemed to offer women a chance to become financially independent, and as The New York Times notes, for a short time it delivered in the form of lighter work schedules and higher pay for seamstresses.

Seamstress work shifted to factories

Another way the invention of a reliable sewing machine changed modern life was the way it shifted the work of seamstresses from the home to the factory. Prior to the introduction of the sewing machine, History Today notes that most seamstresses worked out of their homes or in unsanitary, unsafe workrooms or cottages. And more women worked at sewing at home for their families, endlessly moving a needle to repair or make clothes, something BBC News notes was regarded as "a dull round of everlasting toil" by many women.

But the sewing machine changed things. History Today notes that by 1862, the vast majority of sewing machines were purchased by garment companies, not individuals. The machines were very expensive for their time, and while there were novel "rent to own" payment plans, you had to have good credit to begin with to take advantage of them. As reported by Stocks Embroidery and Sewing, sewing work that had been done in the home was now moving into factories, where large numbers of sewing machines could be used to vastly increase the rate of production. As a result, many women who had plied this trade privately suddenly became something new for them: Employees.

The sewing machine changed fashion

The sewing machine's incredible efficiency altered the way we dress forever. Prior to a functioning and reliable design for a sewing machine, it took an incredibly long time to make a single garment, which made clothing expensive and often bespoke, as noted by History Today. Most men's clothing was actually made in the home before the rise of the garment industry was made possible by the sewing machine, and according to Stocks Embroidery and Sewing Solutions, the sewing machine meant that all members of a household could suddenly afford to own their own individual outfits.

The sewing machine and the speed at which clothing could be made launched the mass production of garments, which in turn drove style and fashion. As noted by The American Enterprise Institute, the sewing machine made possible increasingly elaborate designs, and allowed for those designs to change constantly because of the speed of production.

One downside to the increasingly ornate nature of clothing — especially women's fashions — was the additional time and attention required to create these complex garments. This reduced the speed benefits of the machine for seamstresses, and women working as seamstresses often found themselves working harder than ever despite having the benefits of a sewing machine.

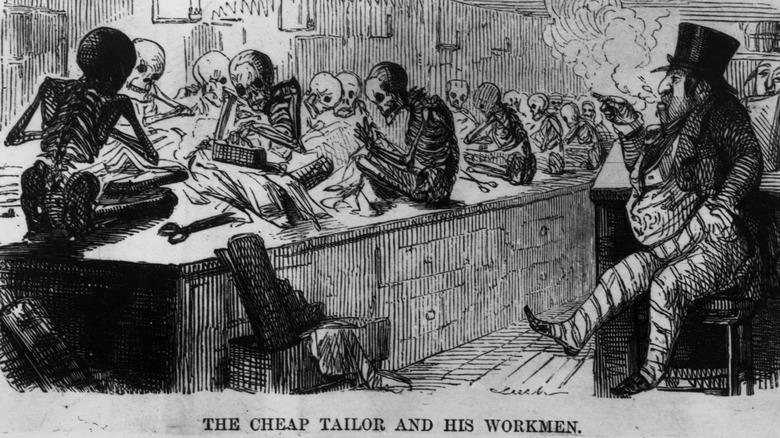

It led to sweatshops

The sewing machine changed how clothing was made, which meant it affected the lives of women much more powerfully than those of men. But the impact wasn't equal. As noted by History Today, wealthier women who could afford one of these expensive machines (which cost $125, an enormous amount of money at the time, per Time) did find making or repairing clothes for their families much easier, and they could also afford to hire a seamstress to work on the machine in their home to produce fashionable clothing. For women with money, the sewing machine was liberating.

For women of lower economic status, the effect was the opposite. They couldn't afford their own sewing machines, and they often found that, when hired to make clothing on a sewing machine, they were expected to work much faster than before — and for less pay.

Worse, as reported by The Mill Museum, most sewing machines in the mid-19th century were purchased by manufacturers in bulk. They were installed in large warehouses or other buildings, and seamstresses were hired at very low wages to work long hours in unsafe, unhealthy conditions. In other words, the sewing machine led directly to the establishment of what came to be known as "sweatshops." The sewing machine ultimately did nothing for poor working women, aside from shifting their misery from the home to the factory.

The sewing machine's impact went beyond garments

The sewing machine changed how clothes were made, making more elaborate designs and the mass production of clothing possible. It also changed the lives of the people — primarily women — who did the work sewing all those clothes, mostly for the worse.

But the impact of the invention didn't end with garments and labor practices. It had a wide-ranging influence on a whole slew of industries. For example, the sewing machine revolutionized how shoes were made. As noted by Foster's Daily Democrat, prior to the invention of the sewing machine, shoes were very expensive to make by hand and usually required an itinerant shoemaker who would measure feet, cut leather, and sew them by hand.

But according to Farm and Dairy, the mechanization made possible by using a sewing machine to stitch shoes changed everything, and by 1880 had reduced the cost of making a pair of shoes to just 3 cents. The invention brought similar changes to the making of saddles, harnesses, and military uniforms. When the Civil War broke out in 1860, most of the military uniforms in America were imported. Five years later, when the war ended, sewing machines were producing all the uniforms the army needed domestically.

The sewing machine indirectly led to women's rights

It's no coincidence that, according to the Mill Museum, the first women's rights convention was held in 1848, producing a "Declaration of Women's Rights" — just two years after the first workable sewing machine was introduced. Initially, the chauvinism and misogyny common at the time led many to believe that the sewing machine was too complex for women to operate. In order to combat this myth, the Singer corporation had women using the machines in store windows and donated them to charitable organizations, soon proving that women were perfectly capable of using them. This set the stage for women to prove they were capable of mastering a wide range of machines and concepts, pushing forward the idea that women were equal to men in all respects.

And as noted by Farm and Dairy, the sewing machine offered more freedom to middle-class and wealthy women because they could spend less time sewing. For the first time, these women had the time to invest in social causes and political movements, directly boosting the suffrage movement and other social causes. The sewing machine's positive impact on women's suffrage was certainly appreciated at the time: According to historian Margaret Finnegan in her book "Selling Suffrage," suffragist writing directly compared the vote to the sewing machine, posing each as a tool women could use to improve their lives.

It erased class distinctions

The impact of the sewing machine wasn't restricted to clothing and the women who originally made it. As noted by The American Enterprise Institute, it contributed to a complete transformation of how class was represented in the U.S.

It changed what clothing meant in a very real way: Prior to the mass production of garments, only the wealthy could afford high-quality, well-fitted clothing, making the divide between rich and working-class extremely obvious. The speed and cost-effectiveness of mass-produced clothing, made possible by the sewing machine, meant that people of any class could afford to be as well-dressed as the more affluent.

This was due in large part to the quality that the sewing machine was capable of producing. As noted by historian Daniel Boorstin in his book "The Americans: The Democratic Experience," the non-bespoke, pre-made clothing that existed prior to the sewing machine and the industrial revolution was usually referred to as "slop" clothes, and no self-respecting person of means would be caught dead wearing them. But the quality of mass-produced clothing in the late 19th century was so high this prejudice vanished, and new terminology had to be invented. The term "ready to wear" was introduced, pushing the focus on the person wearing the clothing and their personal taste.

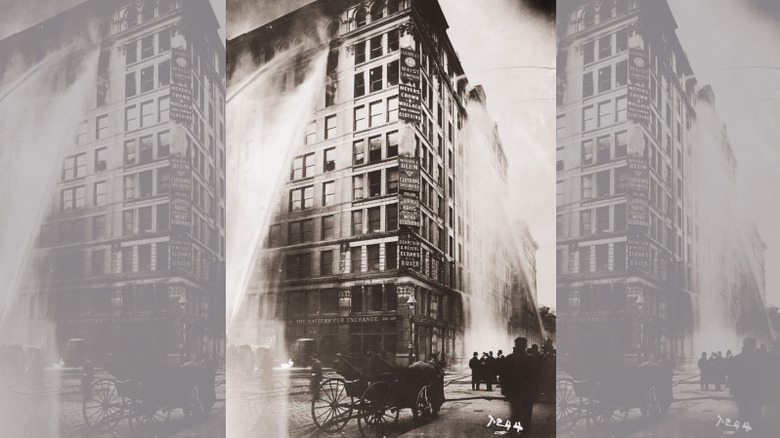

It led to tragedy — and reform

Prior to the introduction of the sewing machine, most seamstresses worked at home or in small cottages, and it took a long time to make a single garment. According to the BBC, sewing machines reduced the time involved in sewing dramatically, and as noted by The Mill Museum, this gave rise to a rapidly growing industry that mass-produced clothing at a scale that would have been impossible without the sewing machine.

This, in turn, led to the rise of what came to be known as sweatshops. Smithsonian Magazine reports that these crowded, unsafe factories were typically crowded with sewing machines set up on long benches. Little regard was given to the safety and conditions that the seamstresses worked under, but this was a common practice even by well-established, respectable businesses.

As History explains, one of these respectable companies was the Triangle Shirtwaist Company. For years women toiled away at its factory in New York City — often locked in to ensure they couldn't take any unauthorized breaks. Then, on March 25, 1911, the factory caught fire — and because of the complete lack of consideration for the workers, 146 people died horribly in the blaze. The tragedy sparked fresh efforts to organize labor and reform working conditions in the U.S., leading to new laws and a revitalized labor movement that changed how workers are treated — which may never have happened if not for the sewing machine.