Who Was Margherita Sarfatti, Benito Mussolini's Mistress?

We may receive a commission on purchases made from links.

Behind every man is a powerful woman — or so the old cliche goes. In Benito Mussolini's case, there were many women behind him. According to "Claretta: Mussolini's Last Lover" (via The Italian Insider), the dictator maintained numerous mistresses and casual partners in addition to his wife of 30 years, Rachele. His final and perhaps most famous mistress, Clara Petacci, was even executed alongside him (via History).

But before Clara, Mussolini preferred his women on the older, more sophisticated, and mature side — and there was one in particular that stood out. Although not as famous as Petacci, Mussolini's most important mistress bar none was the wealthy Venetian socialite and erudite Margherita Sarfatti. Now, she has drawn interest from historians because she was his closest confidant and, in many ways, a founder of fascism — but also because she was Jewish. Although mostly lost to wider audiences, the brilliant and cultivated Sarfatti can be rightfully called the woman who picked up a modest newspaper editor and molded him into "il Duce," Italy's dictator that would eventually drag the country into history's bloodiest conflict. Here is her fascinating story.

From wealthy beginnings

Margherita Sarfatti was born in the lap of opulence. According to the Encyclopedia of Jewish Women, Benito Mussolini's future mistress was born in 1880 in Venice, the scion of the wealthy Venetian Jewish Grassini family. Her family owned a palace on the edge of the old Venetian Ghetto and had a distinguished family history within the recently-unified Italian state.

Sarfatti's early life was filled with well-connected relatives. Her father, Amedeo Grassini, was an attorney for the City of Venice and counted among his friends Giuseppe Sarto, the man who would later become Pope Pius X — one of the leading Catholic opponents of socialism. Her grandfather Marco was a Knight of the Crown of Italy. Her mother's side ironically included a handful of relatives who would go on to be anti-fascist activists in opposition to Sarfatti's own activities.

Sarfatti was educated mostly by private tutors, including Venetian Biennale founder Antonio Fradeletto, who was also a staunch anti-socialist like Pius X and Sarfatti's father (via "Everyday Life in Fascist Venice"). But despite this ambient or perhaps in reaction to it (a streak that would mark her life), Sarfatti became enamored with the works of Karl Marx and left-wing ideologies such as feminism. Her final act of rebellion against her parents came in 1898 when against her father's wishes, she joined the Socialist Party and married lawyer and Zionist Cesare Sarfatti (her father was an Orthodox Jew opposed to Zionism), per The Forward. She pulled him into her political circles, and his connections launched her career after the couple's move to Milan.

Expanding her political circles

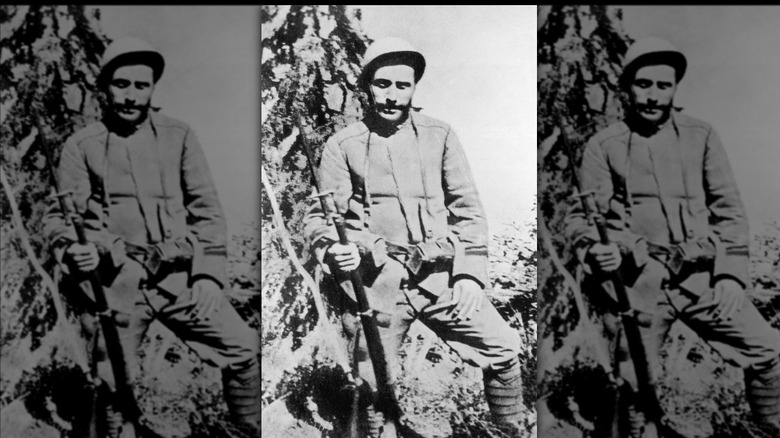

Her marriage to Cesare Sarfatti (above) introduced her to the cosmopolitan world of early 20th century Milan, Italy's intellectual and financial center and hotbed of radical ideas. Soon, she entered his social circles in a foreshadowing of her future political career. First among these was Gabriele D'Annunzio, one of her husband's close friends. According to Britannica, D'Annunzio was a writer and playwright who would go on to make his fame as an Italian irredentist in his attempt to seize the city of Fiume (today Rijeka in Croatia).

She also became acquainted with Russian Jewish feminist Anna Kuliscioff, who was living in Milan. According to the Jewish Women's Archive, Kuliscioff focused mostly on the conditions of working-class women, and Sarfatti was soon drawn to her for her focus on women's issues. Around this time, Sarfatti began her journalistic career. According to the Italian publication La Voce, in 1909, she got a job writing for the Italian socialist magazine Avanti. With this platform, she ran and wrote supporting pieces for Kuliscioff's feminist movement and even bankrolled her through her husband. Thus, Sarfatti's political future was solidified in her early years. But she never would have obtained the influence she achieved after World War I without her crucial interest in art and art history. Her role as an art critic went hand-in-hand with her political activism and helped birth the ideology of fascism.

Margherita Sarfatti, art critic

Margherita Sarfatti, as noted in the Italian arts magazine Cambi, was an avid collector of modern art. But she was also one of its biggest promoters. According to the Jewish Women's Archive, in 1909, she and her husband began hosting informal gatherings of artists at their Lake Como villa. Among them was Filippo Marinetti, the founder of Italian Futurism, which the Guggenheim Museum says was an avant-garde artistic movement that "exalted the new and the disruptive," focusing primarily on the industrial and technological innovations of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Sarfatti promoted Marinetti and other artists in her circles through Avanti.

According to Britannica, Futurism was very much compatible with the socialism of the early 20th century. The movement, much like socialist ideologues, sought to push back or even wipe away traditional values in favor of a modern, technical society. As seen in a portrait of a ballerina by futurist Mario Sironi (via Cambi), it broke with historical Italian depictions of people, which were historically rooted in the Classical and Renaissance traditions. This was Sarfatti's original artistic background. But a series of events saw her expelled from the socialist party. She subsequently abandoned the avant-garde in favor of a more traditionally-inspired modern movement called "il novecento." But it was not purely of her own doing — she had influence from the man that would become il Duce.

Meeting il Duce

In 1912, Margherita Sarfatti's publication Avanti received a new boss (via Jewish Women's Archive). He was a young member of the Italian Socialist Party (PSI) named Benito Mussolini. He became Avanti's manager and Sarfatti's superior. Sarfatti was drawn to the new editor, whom she described (per Haaretz) as a handsome womanizer and implacable socialist with a "glint of fanaticism" in his eyes. But at the time, it was simply a workplace affair that Sarfatti”s husband Cesare tolerated.

Sarfatti's association with Mussolini, however, changed the course of her life. According to historian Brian Sullivan (via the American Interest), Mussolini and Sarfatti had diverged from standard Marxism into a mixed (but not yet fully defined) ideology that combined socialism with Italian nationalism. Thus, when World War I broke out, Mussolini was an ardent supporter of Italian intervention in the war, while his bosses in the PSI wanted to stay out of it. So Mussolini left Avanti, founded his own paper called "Il Popolo d'Italia," and was promptly expelled from the PSI. He signed on and went to fight in the trenches of World War I (above).

By 1914, Sarfatti's positions had evolved to favor military interventionism, perhaps under the influence of her friend and confidant Gabriele D'Annunzio. Thus, she followed Mussolini and became Il Popolo's primary patron and caretaker while Mussolini was fighting on the front lines. Eventually, this mixed ideology of socialism and nationalism, pending a firmer ideological platform and some additions, became fascism.

Family tragedy

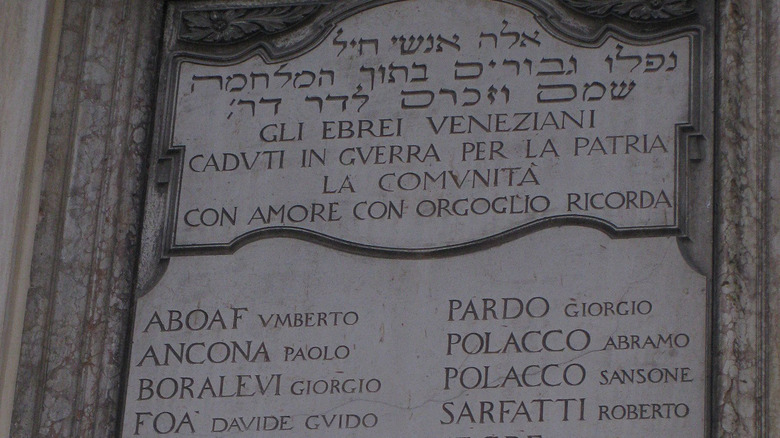

Margherita Sarfatti's family life was not the happiest. As noted in the Jewish Women's Archive, her politics and marriage created rifts with her parents. Her sister Lina responded to widowhood by committing suicide in 1907. In 1918, tragedy struck again when Sarfatti lost her eldest son Roberto in World War I — a conflict in which she had favored Italian involvement.

Roberto Sarfatti enlisted in the Italian Army at age 17 and was sent to fight with the elite Alpini mountain troops in Northeastern Italy, where his grave stands today. He was killed in action while fighting against Austro-Hungarian troops. Roberto's devastated mother memorialized him in a book of poetry called "The Living and the Shade." Less expected was the glowing obituary he drew from his mother's lover Benito Mussolini in Il Popolo.

Mussolini idealized the younger Sarfatti as an Italian hero. The future Italian dictator recalled the first encounters with Roberto, noting that despite being a young, quiet boy, he still burned with the desire to go fight for his country — even as an underage teenager. Per Mussolini, the sacrifices of youth like Roberto were all the more admirable because these young men had placed service to their country above living their lives — something a man who died at 30 could not say. Roberto and his fellow soldiers were heroes, and Italy would be best off singing their praises — a glowing tribute by any standard. The author of the salute to the fallen Jewish soldier eventually joined Adolf Hitler in adopting anti-Jewish policies.

From mistress to global renown

Margherita Sarfatti was many things — art critic, journalist, political activist. But it was her position as Benito Mussolini's mistress and her subsequent related projects that catapulted her to international fame, thanks in no small part to her intimate knowledge of the future dictator's life. But Mussolini may have never become a dictator without her influence.

Mussolini took power in 1922 following the famous October March on Rome. But according to eyewitness Marco Augusto Frigerio (via la Provincia di Como), Mussolini was unsure that the march would be successful, fearing it might turn into a bloodbath. So before the march began, Mussolini stopped at a villa on Lake Como called "Soldo" — the vacation home of none other than Sarfatti herself — and confessed his misgivings to her and his compatriots. Sarfatti allegedly told him, "You will march or die. But I know you will march."

Mussolini did and was triumphant. Sarfatti became the right hand of one of Europe's leaders. Thus, in 1925, she published a biography of Benito Mussolini, which became a bestseller thanks to its intimate portrayal of the dictator. The book generally lionizes Mussolini, making it more of a sympathetic account of how the dictator rose to power rather than pure biography. Sarfatti had practical reasons for doing so: In tying her political destiny to Mussolini, Sarfatti had become the mother of fascism, an ideology she helped create and defend until it backfired on her.

Fascism's mother

Margherita Sarfatti was a signatory of the Manifesto of Fascist Intellectuals, which framed the movement as the continuation of the Italian nation's spirit and history. Now, Sarfatti realized that the ideology needed an anchor in Italian culture to make this statement more than rhetoric, so she settled upon Italy's rich artistic heritage, which she argued had been sidelined in favor of more established French avant-garde artists even inside Italy itself.

According to "Margherita Sarfatti and Italian Cultural Nationalism," Sarfatti sought to give fascism prestige by framing its art in continuity with Roma and the Renaissance — the two most notable periods of Italian high culture. Fascism would herald the "second Italian Renaissance" that would restore Italian artistic supremacy at France's expense. Sarfatti's answer to France's avant-garde style, which she decried for its lack of human representation and deviation from classical forms, was il Novecento. The very name hearkened back to the Quattrocento school of the Renaissance, whose most famous member was Piero della Francesca. Novecento style sought to harmonize modern art forms with the Italian tradition of human representation best captured in classical and Renaissance art. But fascism did not create the Novecento style. In fact, some of its artists were wary of Benito Mussolini.

Under Sarfatti's advice, Mussolini instead promoted art through state patronage, prizes, and conferences, seeking a middle ground between state needs and individual creativity without sabotaging the production of art. Alongside her projects for preserving and rejuvenating local Italian culture, Sarfatti hoped to reclaim the glory of Rome with Mussolini as her caesar.

The cult of il Duce

Per the book "Right-Wing Women," Margherita Sarfatti was not only known as fascism's image maker but also as Mussolini's personal propagandist. Sarfatti created a sort of cult around Mussolini in her biography of the dictator, focusing primarily on Italian women and, by extension, men as well. In Mussolini's biography, Sarfatti wrote, addressing the dictator directly, that the work was a "woman's book" that placed Mussolini in a quasi-religious context as the light and savior of Italy.

Sarfatti first set up the Italian dictator as the natural leader of his people. She first tied him in with Rome, calling him an "archetype of the Italian ... Roman from top to toe." Mussolini was from the Emilia-Romagna region; its capital, Bologna, was known as a center of Renaissance art. Sarfatti wasted no time in creating an implicit association between the achievements of the past and Mussolini in the present, implying that Emilio-Romagnan Mussolini was destined to continue the cultural achievements of his countrymen.

Finally, Sarfatti had a large collection of anecdotes to choose from to build Mussolini's virile and savvy political image. For instance, she stressed his toughness by recounting a story of how a young Benito slashed a bully's face with a stone for stealing his wheelbarrow. Later, she described his review of his Blackshirts in Rome from horseback amidst the ruins of ancient Rome, no doubt drawing parallels between the dictator and the Roman generals of old. However, according to The Forward, she omitted the more intimate aspects of their relationship, in particular sexual matters and drug use. Those surfaced in a later memoir.

Fall from grace

In the 1920s, Margherita Sarfatti seemed to have a lock on Benito Mussolini. According to the Jewish Women's Archive, she was a well-known writer for the fascist magazine Gerarchia, was Mussolini's inseparable companion, and had devised the visual aspects of Italian fascist culture herself. But her influence began to wane by the late 1920s and early 1930s.

Per The American Interest, Sarfatti began facing attacks from within Italy's National Fascist Party, which accused her of using her influence to benefit foreigners and advance her own hold over Mussolini to the detriment of everyone else. According to Prof. Piero Foa, whose family knew Sarfatti, Jews in Italy increasingly came under attack in the press from elements sympathetic to Nazi Germany — despite Mussolini's public denunciation of these elements. Sarfatti was among those attacked, but she stood by the dictator, even trying to downplay her Jewish ancestry.

In a letter written to Jesuit priest Pietro Tacchi Venturi (via "Pouring Jewish Water Into Fascist Wine"), she mentioned that at some point, she had received Catholic baptism and had her daughter Fiammetta baptized in 1927 at the age of 17. This was perhaps done to stave off anti-Semitic attacks against her, although she remained — at least per a 1956 letter — a Catholic later on. Regardless, Mussolini began to lose interest in her sexually, taking the younger, prettier Clara Petacci (above) as mistress in 1932. Now, despite that, Sarfatti continued to defend Mussolini, even visiting America in 1934 (via Selva) to promote Italy and Italian women in the United States. But her days were numbered.

The racial laws

In 1935, Germany passed the Nuremberg Laws, which, among other things, forbade marriages between Jews and non-Jews. Now, per Prof. Piero Foa, Mussolini originally opposed them and their progenitor, Adolf Hitler. He had discounted German racial supremacy, noting that while Roman Italy was producing literary luminaries such as Virgil, the Germanic tribes were barely literate. Together with Margherita Sarfatti, he published a series of tracts in the 1920s calling on Jewish Italians (as opposed to Italian Jews) to remain in Italy instead of moving to British Palestine, suggesting that Mussolini considered Jews as Italians, contra Nazism. He backed up his words by opposing Germany's 1936 attempt to annex Austria.

So why the shift? As noted in the Review of Politics, Italian and German geopolitical interests converged, leading to the 1936 Rome-Berlin Axis. Italy, however, was the junior (subservient) partner. Per "Italian Fascism and the Racial Laws of 1938," Italy soon had to align fascism with Nazism, so Italians became part of the Aryan race. Jews were banned from a host of positions and forbidden from marrying non-Jews, as had been common before, going from being part of the Italian nation to being a separate nation-within-a-nation. Per The Guardian, Italians were also banned from marrying Africans, a common occurrence in the colonies, where Italian soldiers often took Eritrean wives. For Sarfatti, Mussolini's about face must have come as a shock for her, especially since she had dedicated the 1930s to defending him against charges of anti-Semitism (via Jewish Women's Archive).

Exile

Margherita Sarfatti's reaction to the racial laws was to leave Italy. According to a 1939 communique published in Time, that year found her living in an upscale Paris hotel. Now, she seemed to be in denial about what the future held, which was not unexpected considering that she had been Mussolini's "closest feminine confidant" even up to 1935 after he had set her aside. Speaking to the International News Service, she said, "I have not been exiled ... Please make it clear." Her language suggests that she still loved Mussolini and hoped that he would reverse the racial laws and stop "[paling] around with Jew–tormenting Adolf Hitler," whom she, like Mussolini before 1935, hated (via Time).

According to the art journal Selva, Sarfatti decided not to return to Italy once the war broke out. Instead, she settled in South America, where she became an art critic and had a particularly strong impact in Brazil. Brazilian artists, in particular, many of whom were either educated in Italy, of Italian descent, or both, promoted her work and the Novecento movement she had helped create back in Italy.

Sarfatti remained in South America until 1947, promoting the Novecento style, but soon saw her work undone under the postwar order. Because the Novecento was associated with fascism, it was sidelined as a reactionary style that should be forgotten. When New York's Museum of Modern Art did a 20th-century exposition of Italian art, it omitted almost all mentions of the Novecento, and Sarfatti's life work fell by the wayside.

A divided legacy

Margherita Sarfatti eventually returned to Italy, where she died in 1961. But per The Forward, while writing in the Argentine newspaper Critica, she penned a tell-all series about her relationship with Benito Mussolini, which she published after his death in keeping with her agreement not to divulge his intimate details in exchange for her children's safety. Sarfatti's new portrait of Mussolini depicted a sex-addicted, syphilitic cocaine abuser whose lust for power and alliance with Adolf Hitler doomed him, but it omitted intimate sexual details. She blamed herself, noting that "[she had] believed in fascism and fought for it in the beginning."

Unexpectedly, Sarfatti's legacy is taboo; she never discussed it even with her own family. As her granddaughter Ippolita Gaetani discussed with Haaretz, many Italian Jews supported fascism, which the Jewish Sarfatti helped create. Yet, the fascists that she had encouraged to seize power in 1922 eventually cooperated with the Germans that deported her sister Nella to her death in Auschwitz. Ultimately, Ippolita notes that her grandmother relished the deadly combination of fame and powerful men — and she surrounded herself with them. When she met the young and ambitious Benito Mussolini, it seemed like destiny. But as Ippolita noted, Sarfatti was conflicted by the end. She never discussed the details of her personal life with Mussolini nor whether she felt any guilt for her sister's death. All the mother of fascism had to say for herself was that il Duce was at his best when he was with her.