The Crazy True Story Of West Point's Eggnog Riot

West Point Military Academy has a long history of producing famous military and civilian leaders stretching back hundreds of years (via West Point). Today, it ranks fourth among the nation's universities and colleges for its high concentration of Rhodes Scholars, numbering 90 (as of 2022). Despite stellar academic positioning, a debate emerged in the early 2000s about the effectiveness of the academy's training techniques, as reported by Foreign Policy. On the one hand, many former cadets defended the academy, citing its historically impressive alumni rolls, which include just about every Civil War notable (on both sides).

On the other hand, a smaller subset of former cadets argued that West Point has an unfortunate predilection for creating impetuous, petulant officers. Need we say more than Gen. George Armstrong Custer? One graduate observed with acidic acuity, "Many of my experiences at West Point fly in the face of any idea I ever had about the nature of good leadership" (via Foreign Policy). Although the debate continues about West Point's approach to shaping America's future leaders, one thing can't be disputed: The academy remains a beacon among military educational institutions.

Surprisingly, West Point once weathered a riot of epic proportions, per Smithsonian Magazine. The rowdiness took place on Christmas Eve and on Christmas Day in 1826, and it involved — you guessed it! — boatloads of boozy, creamy eggnog. Here's what you need to know about the infamous Eggnog Riot and some of the famous figures caught up in the rum-fueled mayhem.

West Point started with a bad rap

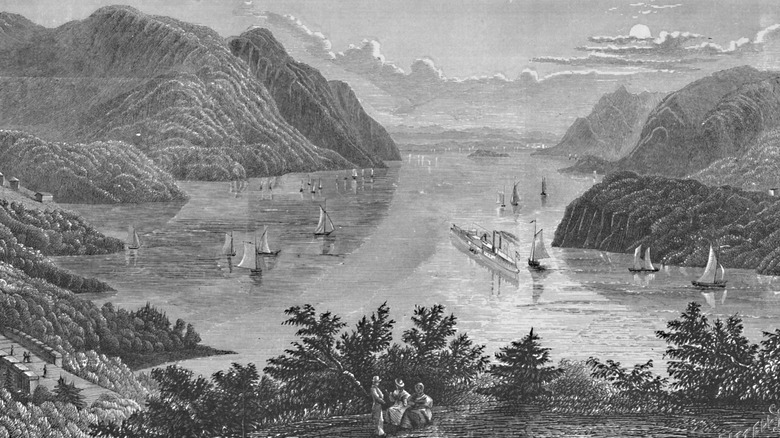

The military academy at West Point officially opened its doors in 1802, according to the United States Military Academy West Point. But West Point's location — on New York's Hudson River — had long-enjoyed a storied history, having played a vital strategic role during the American War for Independence (via the Library of Congress). Both Colonial and British forces recognized the crucial tactical importance of the site located on the Hudson River's west bank. Because of its military location, West Point is still referred to by some as the Gibraltar of the Hudson. And the academy sitting there boasts the motto "Duty, Honor, Country," per Battlefields.

To buttress the position, Gen. George Washington contracted Polish engineer Taddeus Kosciuszko to fortify the position. And it's no coincidence that the British wooed Maj. Gen. Benedict Arnold, hoping he'd surrender the location to them in 1780. Luckily, that never happened. After the war, Washington proposed opening a military academy at West Point. But he faced pushback from other Founding Fathers, like Thomas Jefferson, who felt apprehensive about keeping a standing army. By 1802, however, the school opened with even Jefferson acknowledging its inherent utility.

Nonetheless, hesitancy on the part of government leaders continued to dog the school. As a result, the institution lacked federal funding, organization, and discipline. Its reputation suffered accordingly, per Smithsonian Magazine. Only three teachers instructed a handful of students, and admissions requirements proved anything but stringent. For the first decade, West Point operated as an apprentice school, emphasizing the training of military engineers (via Britannica).

The War of 1812 changed everything

The War of 1812 held disastrous consequences for the United States, ushering in terrible and embarrassing defeats (via History). According to the U.S. Senate, these losses included the capture and burning of Washington, D.C., including the United States capitol and the president's mansion! For America's part, the nation faced off against the greatest naval superpower on the planet, vastly outnumbered and out-shipped by Great Britain. Despite all odds and harrowing military disasters in countless individual battles, the nation survived, later declaring the conflict its "second war of independence."

Of course, so much trauma had a lasting influence on the American psyche. In particular, the conflict drilled home the necessity of investing in the military and keeping a standing army (via Smithsonian Magazine). It also pointed to the need for excellent military leaders with an impressive breadth of knowledge regarding the latest military technologies and engineering feats. In keeping with this sentiment, Congress passed an act on April 29, 1812, which increased enrollment at West Point to 250 cadets. The act also reorganized the academy, paving the way for a revamped reputation, per Britannica.

Not only did Congress send more money the school's way, but as told by American Heritage, they also enlisted former West Point graduate Col. Sylvanus Thayer as superintendent in 1817. Through hard work and increased public support, Thayer transformed a haphazard educational experience into one of the finest in the country. In areas like engineering and science, the school would go unmatched for decades.

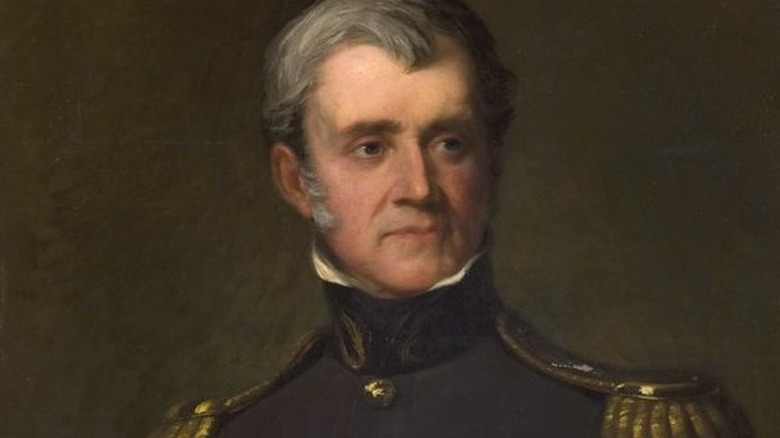

The Father of West Point was no joke

Col. Sylvanus Thayer soon earned the moniker "The Father of West Point," bringing order and discipline to the school, according to Civil Engineering Source. He turned the institution into a highly disciplined enterprise where rules threatened to outnumber students, including prohibitions against cooking in dorms, dueling, tobacco, novels, and drinking (via History). But Thayer proved unique in the sense that he not only walked the walk but talked the talk.

One cadet recalled, "Throughout the day, [Thayer] was always prompt, always courteous, and always looked as if he had just shaved, bathed, and dressed," per American Heritage. Besides tightening regulations, he improved admissions standards and brought a new sense of discipline to the academy. He led efforts to update the curriculum, expand the library, and improve the effectiveness of the pedagogical methods utilized. His efforts and strict discipline improved the academy's public image while increasing the discipline and effectiveness of the military leaders produced.

Another result of his efforts was the production of military technicians capable of tackling civil engineering projects, making it the oldest academy in the country to offer formal education in this field, per the American Society of Civil Engineers. In other words, the education they received would have far-reaching consequences in the civilian world as well. As the nation became increasingly obsessed with the notion of Manifest Destiny and pushing westward, this army of civil engineers took on myriad public works projects necessitated by expansion with aplomb.

Col. Sylvanus Thayer put the 'Bah Humbug!' in Christmas

Nothing says Christmas like eggnog. Many people drink it alcohol-free today. Some even down it with shots of espresso. However, in the early 19th century, eggnog sans rum seemed unimaginable, per Smithsonian Magazine. This stemmed from eggnog's origins. The beverage began as posset, a punch made with hot milk and ale or curdled wine.

First created during the Middle Ages, the upper crust initially enjoyed a monopoly on the cocktail because of the scarcity of dairy. But when it hopped the Atlantic Ocean with the first colonists, eggnog evolved into a drink enjoyed by the masses. The prevalence of the holiday cocktail got further buttressed by the abundance of ingredients available in the New World, including ready supplies of sugar and rum. Even Founding Fathers like Gen. George Washington got behind the holiday sauce, according to History Today. America's first president created his own recipe for the traditional beverage, embellishing it with none other than whiskey, sherry, and brandy.

But all of this Yuletide merriment posed a serious problem for West Point. Over the years prior to Col. Sylvanus Thayer's arrival, the academy had earned a reputation for drunkenness. Among his many tasks, Thayer realized he must wage a decisive war against alcohol on campus. To achieve this, he prohibited the sale, storage, and consumption of spirits at West Point. These dry rules threatened to put the kibosh on Christmas, however, and some West Point cadets would have none of that.

Lessons learned and contingency plan created

Although the cadets at West Point considered Col. Sylvanus Thayer the ultimate party pooper, he had reasons for keeping the campus dry, per History. Case in point, July 4, 1825. In an uncharacteristic move, Thayer permitted the cadets a little imbibing. Apparently, moderation wasn't something the student body (and its officers) excelled at. Excess led to chaos in a relatively brief amount of time.

The loosening of restrictions on alcohol resulted in a so-called snake dance involving academy cadets. To top it off, the school's commandant, a man by the name of William Worth, got carried to the barracks on the shoulders of the students. (Whether willingly or unwillingly, we don't know.) Thoroughly disgusted by the display, Thayer learned an important lesson about leniency. And he wouldn't make the same mistake twice, no matter how momentous the occasion.

He declared a total prohibition on "any spiritous or intoxicating liquor" just in time for one of the biggest celebrations the country had ever witnessed: July 4, 1826. This date marked the 50th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence and the birth of the nation. Nevertheless, Thayer dug in his heels, declaring West Point a veritable Sahara desert regarding intoxicating spirits. Passing this holiday in the mundane grip of sobriety wasn't something the cadets would soon forget. Swearing they'd never suffer another major holiday without booze, a group of proactive cadets made arrangements to secure spirits en masse. They would prove frighteningly successful.

Clandestine booze of every sort fueled the Eggnog Riot

After spending the 50th anniversary of the United States (and biggest party day in the land) sober, West Point's cadets were determined to secret in booze for Christmas, according to History. To ready themselves for the event, the boldest cadets smuggled in gallons of spirits via boat from establishments across the Hudson River like Benny's Tavern, as reported by History Today.

What they used to pay for the booze is a detail lost to history, explains Smithsonian Magazine. But the tavern folks did accept barters of anything unrelated to the academy. In other words, shoes and blankets may have secured the special sauce. Although accounts differ regarding the types of alcohol the West Point Eggnog Riot ultimately entailed, the list is long and likely included at least 1 gallon of rum and 2 gallons of whiskey. Other accounts add gallons of whiskey and brandy to the rum and wine. Should the latter account of available beverages be more accurate, it's safe to say President George Washington's eggnog recipe flowed through the barracks.

If you think this sounds like the makings of an epic party, you're right and then some. The cadets smuggled the booze back into their dorms in preparation for an unprecedented and unrivaled Yuletide party. On Christmas Eve, the drinking binge started in the North Barracks. Into the night, the party gained momentum and noise until it reached a feverish pitch the on-duty officers could no longer ignore.

All quiet in the North Barracks

Col. Sylvanus Thayer assigned Capt. Ethan Allen Hitchcock and Lt. William A. Thornton (listed as a captain by History Today) in charge of the North and South Barracks on Christmas Eve (via Smithsonian Magazine). These proved far from enviable posts that put both men on crash courses with soon-to-be drunken cadets.

Curiously, though, when Hitchcock and Thornton retired to bed, all looked clear and quiet. The officers must've pinched themselves, wondering how they had passed Christmas Eve with no trouble. Of course, they may have rationalized the stakes were high enough to keep the cadets in check. After all, smuggling booze into West Point could lead to expulsion, which seemed like a lot to risk for one night of fun, per History. But four hours later, Hitchcock and Thornton awoke to the realization that their initial assessments had proven way off the mark.

The cadets involved in the drunken debauchery at West Point that night managed to get saucy as quiet as church mouses. At least, for the first few hours. But by the wee hours of Christmas morning, all hell began to break loose ... to put it politely. Not only would Hitchcock and Thornton enjoy a rude awakening, but in their attempts to bring order to the chaos, some drunken cadets turned on them, making for a riotous night far removed from holiday cheer. By the end of it, the 4th of July snake dance looked like child's play.

Drunken cadets targeted their officers

By the time the Christmas party became noticeable in the North Barracks, it had gone dreadfully off the rails, per History. The noise of the Yuletide revelries summoned Ethan Allen Hitchcock from a deep sleep at 4 a.m., and he quickly dressed and rushed out into the hallway "to ascertain if there was any disorder in the barrack." The boisterous nature of the party in room five soon drew his attention. He entered to find 13 cadets sloshed.

About this time, Cadet Jefferson Davis, the future president of the Confederacy during the Civil War, burst into the room. A mixture of poor timing and bad judgment led him to scream out to his fellow partygoers to get rid of the booze because Capt. Hitchcock was on his way. This declaration likely came with an awkward pause and maybe a little throat clearing as the other cadets let Davis know that an astonished Hitchcock stood among them.

Hitchcock acted with speedy sobriety, banishing Davis to his room. Then, he enunciated the Riot Act to the 13 cadets, all still three sheets to the wind. The Riot Act declared no more than 11 men could assemble at a given time and place. But in their mutual stupor, the cadets proved bold and decided to resist. They even attacked Hitchcock. In the South Barracks, William A. Thornton fared worse, getting knocked unconscious in the Christmas fervor, according to History Today.

The Eggnog Riot's aftermath was ugly

"Reveille" looked anything but blissful the next morning, according to History Today. While the North Barracks took the brunt of the damage, the South Barracks also contained the markers of inebriated mayhem. Smashed furniture, broken windows, and banisters ripped from stairs characterized the total disarray of the academy, per HowStuffWorks.

The cadets that participated in the night's bacchanal brouhaha felt so dreadfully hungover they could barely stand, let alone muster. Remorse followed fast on the heels of splitting headaches, spinning equilibriums, uncontrolled nausea, and aversions to bright light. What's more, a simmering animosity flowed between Ethan Allen Hitchcock, William A. Thornton, and the cadets they were charged with keeping safe and sober.

Per the United States Army, as details emerged about the happenings on the night of December 24 and the wee hours of Christmas Day, many cadets faced punishment. Approximately one-third of the academy's students participated in the Eggnog Riot (via Mental Floss), which meant Col. Sylvanus Thayer found himself between a rock and a hard spot. West Point remained in its infancy, and expelling that much of the student body would've crippled the institution. That said, individuals still had to be held responsible for their boozy actions. All told, 19 cadets got court-martialed, 11 faced expulsion, and six cadets resigned (via the U.S. Army).

As for Jefferson Davis, he remained confined to his quarters throughout the month of January.

Crime, punishment, and institutional reputation

Col. Sylvanus Thayer had a tough call to make, and he chose to focus on the 22 cadets most deeply associated with the drunken debauchery, according to History. Over the next month, investigations led to court-martials for 19 cadets and one soldier. During the trials, a whopping 167 witnesses testified, including Robert E. Lee. While the future general of the Confederacy hadn't participated in the riot, Lee offered defensive testimony for fellow classmates, as reported by the United States Army.

By mid-March, the court-martial proceedings concluded. Of the 19 defendants charged, all were found guilty and faced dismissal. But clemency recommendations saved nearly half of them, with five eventually graduating. Fifty-three other cadets faced lesser charges and punishments. To this day, the Eggnog Riot holds the title for the largest expulsion of students in the academy's history (via Task and Purpose).

Per Smithsonian Magazine, none of the buildings from the Eggnog Riot still stand. Instead, new barracks with short hallways were built in the 1840s to ensure cadets could only access other floors by exiting the building completely. Sherman Fleek, West Point's command historian explains, "When they built those, they put in a measure of crowd control. It would make it more difficult for [cadets] to get out of hand and gather in large number."

Large holiday celebrations are still discouraged at West Point to this day, with access to alcohol extremely limited. What's more, the salacious intoxication that led to the events on December 24 and 25, 1826, remain largely unknown to 21st-century cadets.