The True Story Behind The First Black Woman To Serve In The US Army

In the years after the Civil War ended in 1865, formerly enslaved people had to find a way to survive. The Low Country Digital History Initiative confirms that around 4 million Black people were suddenly free, but their choices remained limited. Women, who were largely limited to domestic work, especially suffered. Their choices mainly included continuing to work for white farmers or trying to make it on a small piece of their own land, all while battling to maintain the family unit and their religious freedoms. Among their numbers was Cathay Williams, whom Black Past verifies was born with slave status and was enslaved for the duration of the Civil War.

Williams likely saw more military life than others in her class. Her last wartime position was in 1864 when she worked as a cook and laundress for Union General Phil Sheridan. When the war ended, however, Williams was "without a job," according to biographer and poet Linda Kilpatrick. In an 1876 interview, Williams remembered being shuffled around to Iowa and, finally, Jefferson Barracks in Missouri. Desperately in need of money and independence, she did the unthinkable: In 1866, Williams enlisted in the United States Army — as a man. Read on for the fascinating story of the first Black woman to serve in the U.S. Army.

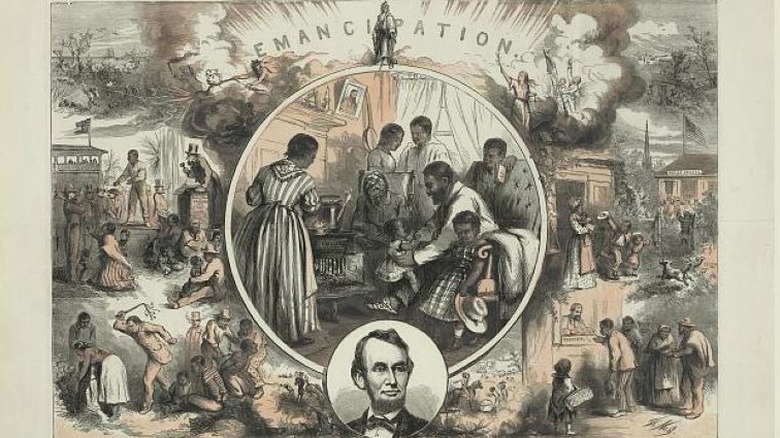

Black women had few choices after emancipation

In the time immediately after the Civil War, the government embarked on Reconstruction, which History explains as the effort to integrate Anglos and Blacks into one big free society. The Civil Rights Act of 1866, reports Ballotpedia, gave all Americans "the absolute right to live, the right of personal security, personal liberty, and the right to acquire and enjoy property." But several Southern states enacted "black codes," which National Geographic explains posed such limitations as what kinds of jobs Black people could work, their ability to leave one job for another, and restrictions on what sort of property they could own.

Black women, submits the New York Historical Society, fared worse than their male counterparts. They were forced to keep working to support their families, often while trying to find lost family members who had been sold or taken away during their enslavement. They were also eager to learn, since many of them were never taught to read or write. In 1865, according to the National Archives, the Freedmen's Bureau was formed to help those being discriminated against. At risk were those whose employers made Black people sign contracts to work grueling hours, refused to pay them, and even exhibited violence against them.

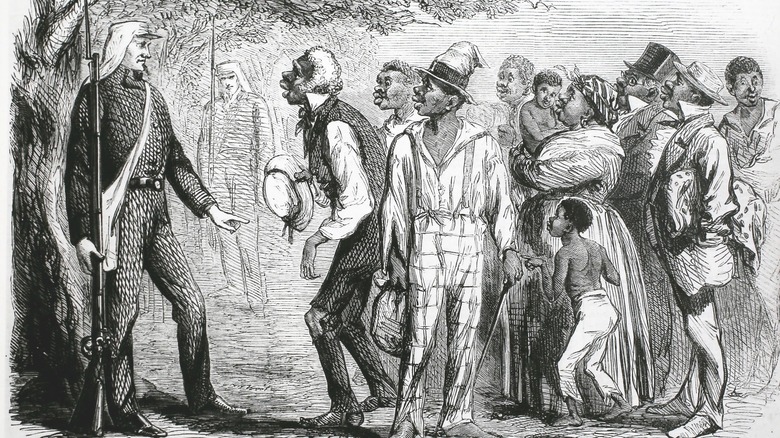

Cathay Williams was considered contraband during the Civil War

Cathay Williams' life began in a slave cabin outside of Independence, Missouri. Historian Phillip Thomas Tucker's biography about her states she was born in 1844 to a free Black man and an enslaved Black woman, identified as Martha in an article in Colorado's Pueblo Chieftain newspaper. Because of Martha's slave status, Williams also was considered a slave. Her enslaver, whom she identified as William Johnson, moved the family to Jefferson City while she was still quite young. But Johnson died just before the Civil War broke out, and Williams would soon be considered "contraband."

The National Park Service defines "contraband" as enslaved people who crossed Union Army lines. By doing so they were considered to have escaped, and if they had worked for anyone in the Confederacy, they "were declared free." But they were not really free. Wounded Warrior Project explains that Williams was technically "a captured slave" and was made to do whatever the Union wanted her to do. Most sources call the type of work Williams was assigned to as being "pressed" into service. The National Trust of Historic Preservation further explains that contraband slaves were forced to follow Union troops and do their bidding while living in "hastily erected" camps.

She was forced to serve as a cook for Union troops

In an 1876 interview in the St. Louis Daily Times (via Phillip Thomas Tucker's "From Slave to Female Buffalo Soldier"), Cathay Williams said that between 1861 and 1865, she was taken through Arkansas, Louisiana, Georgia, Washington, D.C., and Virginia. She had always been a "house girl," and learning to cook for the troops was hard. African American News & Issues writes that with her limited cooking skills, Williams was also taught to do laundry. Her life was not easy, for she was forced to follow the troops through the wilderness, rain, snow, or shine, and was expected to perform her duties no matter how weary she was.

Eventually, Williams warmed to military life. In August of 1864, she was working for General Philip Sheridan's troops (pictured) when they rode to the Shenandoah Valley to chase out Confederate forces (per History). Williams is said to have been there on her own free will. Afterward, she was sent to Iowa and finally Jefferson Barracks in Missouri, which NPR describes as a military station serving as a "troop mobilization point." With the Civil War at an end, Williams said she wanted to "make my own living and not be dependent on relations of friends." But how could she accomplish this?

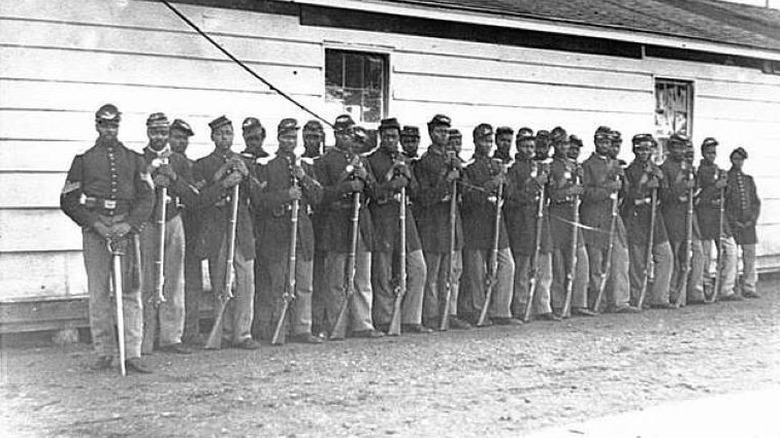

Cathay Williams, the first and only female Buffalo Soldier

In his book "Sick from Freedom: African-American Illness and Suffering During the Civil War and Reconstruction," author Jim Downs explains that freed slaves after the war ended in 1865 were largely left to fend for themselves. Many formerly enslaved people immediately became destitute and died of disease or even starved to death. As Cathay Williams pondered her fate, a seeming miracle happened: In 1866, reports the official Air Force website, Congress organized four special Black cavalry and infantry units. They were called the "Buffalo Soldiers." Nobody is sure where the name came from, but it soon became a standard reference for these special forces.

For Williams, joining a regiment of Buffalo Soldiers seemed a viable way to survive. But according to the National Park Service, the trouble was that women were not allowed to enlist. The desperate Williams did the next best thing. She would later state that "two persons, a cousin and a particular friend," were also serving as Buffalo Soldiers (per Wounded Warrior Project), which gave her the courage to enlist as a man. As of November 15, 1866, according to biographer and poet Linda Kirkpatrick, Cathay Williams became William Cathay, Buffalo Soldier. Since the Army didn't require full medical examinations at the time, it wasn't hard for her to masquerade as a man.

She literally walked 1,000 miles as a soldier

According to True West magazine, Cathay Williams was enlisted in the Army as a cook. Anna Maria Gillis of the National Endowment for the Humanities magazine goes into more detail, explaining that Williams' regiment took a train to Fort Riley and Fort Harker in Kansas, beset by cholera at the latter place. Next came marching on foot to three different forts in New Mexico. Author Phillip Thomas Tucker guessed Williams walked more than 1,000 miles while in the Army. She probably received around $13 per month, according to the National Park Service. And somehow, she managed to keep her true sex a secret.

Most unfortunately, being a soldier in the Army also came at a cost. Constant travel and the weather soon took its toll on Williams' health. Documents at the National Archives include original affidavits showing Williams was too ill for duty during 1867, had contracted smallpox, lost nearly all of her toes due to frostbite, suffered from rheumatism and neuralgia, and developed "itch," defined by the National Library of Medicine as a pruritic dermatosis. Officials back in St. Louis had already begun to process Williams' discharge in September of 1868 when she contracted smallpox for the second time in October, and suffered "deafness" after being made to swim across the Rio Grande River in New Mexico.

How her secret was discovered

Cathay Williams' various ailments seem to have been largely ignored by the Army. Smithsonian Magazine writes that Buffalo Soldiers, who were nearly always commanded by white officers, often suffered from racial prejudice and were mistreated. Black Past says Williams had marched to Fort Bayard in New Mexico Territory when she decided to leave the military. In her 1876 interview (per National Endowment for the Humanities), Williams explained that she had tired of the military "and wanted to get off." Although she was already suffering, Williams also admitted, "I played sick." Soon enough, the post surgeon gave her a thorough exam and finally discovered her true sex.

That Williams had fooled the authorities for so long is truly amazing. Legends of America counts five different times when Williams was hospitalized during her service, in four separate hospitals. Yet somehow her true gender went undetected. Certainly many of her fellow soldiers were shocked and dismayed, and some of them were not happy to discover they had been working alongside a woman. Wounded Warrior Project quotes Williams as saying, "The men all wanted to get rid of me after they found out I was a woman. Some of them acted real bad to me."

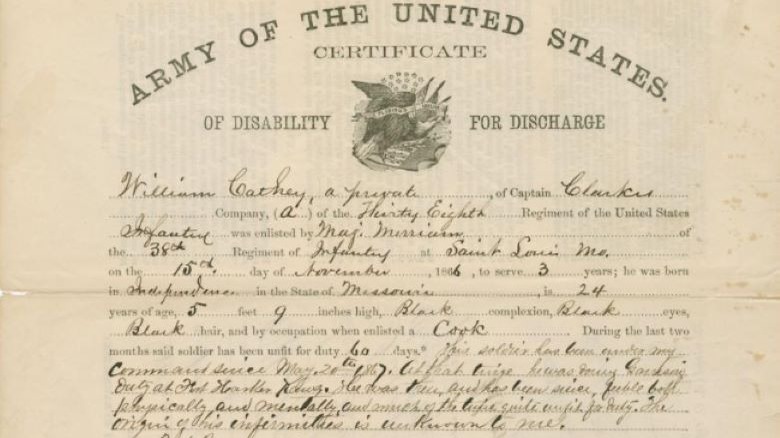

Cathay Williams received an honorable discharge even after being found out

One would think that being discovered a virtual fraud in the United States Army would result in a court martial, or at the very least being shunned by the military. In actuality, says the National Archives, women found to be serving as soldiers were sometimes revered. In Cathay Williams' case, being Black made her unique. And after all, woman or no woman, African American News & Issues submits that Williams was a good soldier who carried out her duties faithfully from 1866 to 1868. Her only real downfall was her health. But she did not suffer her illnesses and ailments due to her sex, points out biographer Phillip Thomas Tucker, but because she was a soldier.

In the end, Williams was officially discharged not because she was a woman, but because her disabilities prevented her from serving further. Her original "Certificate of Disability for Discharge," signed by commanding officer Captain Charles E. Clarke, confirms that Williams had frequently been "feeble both mentally and physically," and "quite unfit for duty." Notably, Clarke addressed Williams as her male alter ego and mentioned nothing about her being female. Legends of America reiterates that her discharge was honorable.

Williams' terrible marriage and time in Colorado

According to Cathay Williams' 1868 disability discharge, her address was documented as Alton, Illinois. But an 1891 affidavit verifies she was at Fort Union, New Mexico (shown here in ruins), between 1869 and 1870. Fort Union had been established in 1851 to protect travelers along the Santa Fe Trail, according to a National Park Service brochure. While at the fort, Williams worked as the cook for a colonel's family, she said (via African American News & Issues). She likely witnessed extensive renovations being completed on what would be the third and final phase of Fort Union. The fort later closed for good during the 1890s.

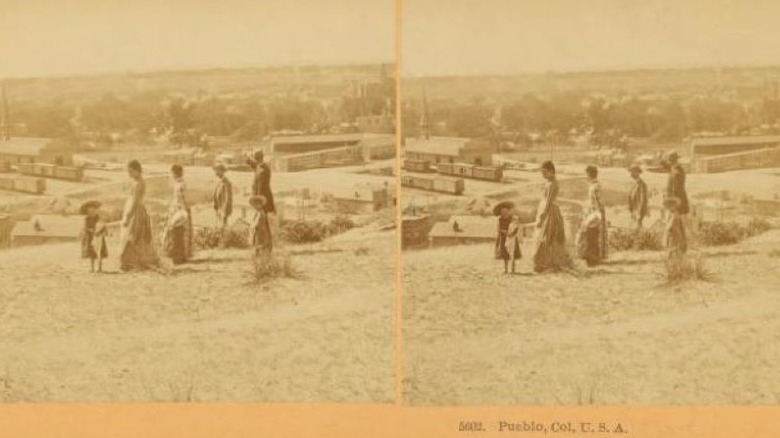

In 1870, Williams next decided to move to Pueblo, Colorado, where she took a job doing laundry, reports the Pueblo Chieftain. According to Wounded Warrior Project, Williams may have worked as a seamstress, possibly under the name of Kate Williams. She later stated that she married a man while in Pueblo, but that he "was no account," meaning no good (via African American News & Issues). The man managed to steal Williams' watch, $100 of her money, and even her horses and wagon. Luckily, she was able to get him arrested and thrown in jail before leaving town. To date, nobody has found a record of her marriage.

Her life in Las Animas and Trinidad

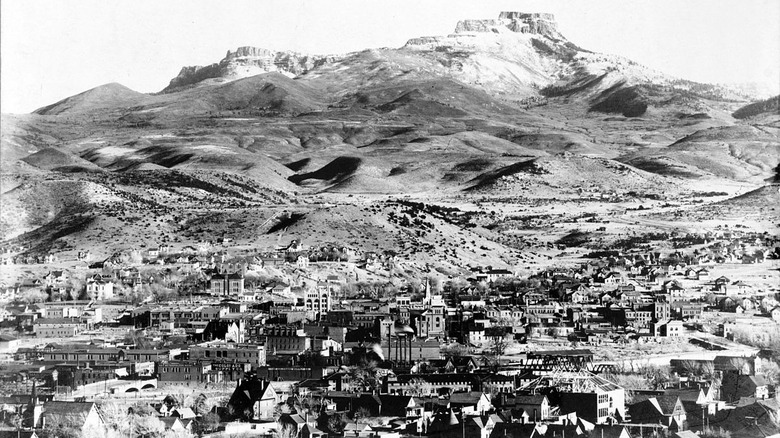

In the early 1870s, Cathay Williams relocated to the town of Las Animas, where she again worked as a laundress. Phillip Thomas Tucker speculates that she might have been quite at home in Las Animas' own African American community. History Colorado confirms that nearby Fort Lyon was home to numerous Buffalo Soldiers from the 10th Cavalry division during the 1860s and '70s. Interesting is that Williams only remained in Las Animas for about a year; by 1873, she had relocated yet again, this time to Trinidad (pictured) near the New Mexico border. According to Legends of America, Williams worked there as both a laundress and a nurse.

In her 1876 interview, Williams told about her time as a Buffalo Soldier. She also talked of how she liked Trinidad and "the good people" there, and said she hoped to secure some land. But she never did get her land, and she does not appear in the 1880 census for Trinidad. The only concrete evidence of her presence there was an 1890 article in the Pueblo Chieftain that reported Williams was living in a "shanty" in Trinidad and had been "without fire or food" for several days. The sickly woman was taken to the hospital, where she remained for nearly a year and a half.

Why was she denied her pension?

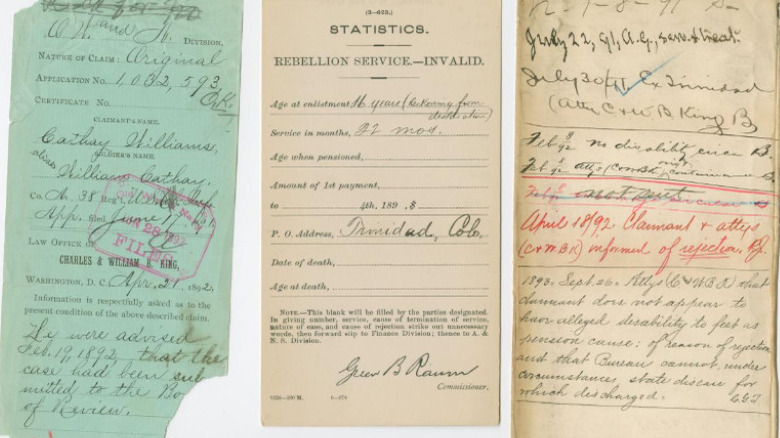

Upon being released from the hospital in 1891, Cathay Williams was now destitute, according to Legends of America. Desperate for help, she decided to apply for a disability pension from the military. Her Civil War Pension file confirms that she was certified an invalid as of June 19, 1891. What happened next was both disappointing and sad. In his book "Voices of the Buffalo Soldier," Frank N. Schubert reports that when she applied for her pension in 1891, three physicians examined Williams. They described her as "a large stout woman in good general health," and noted that aside from walking with a crutch, she had suffered no hearing loss and had no other disabilities.

Original documents confirm that it was not until February of 1892 that Williams' claim for loss of hearing, "Itch," rheumatism, and neuralgia was submitted to the Board of Review. Two months later, the Board rejected her claim based on the examinations she received. Williams and her attorneys appealed, but in 1893 the claim was denied again because she "does not appear to have alleged disability to feet as pension cause." This was despite Williams being described as having "constant illness" and "feeble habit" during her time as a soldier, and it was hard to miss the crutch that helped her walk. Researcher Diane Williams believes that military officials denied the claim because Cathay Williams had embarrassed them by successfully masquerading as a man.

Cathay Williams was declared insane

With her pension denied, Cathay Williams remained destitute until 1896, when she was taken to Pueblo and admitted to Woodcroft Hospital, an institution for "nervous and mental diseases." In 2010, the Pueblo Chieftain verified that Williams, now known as William Cathey or William Cathay, was admitted on September 26. Puzzling is that a much earlier article in the Colorado Daily Chieftain, in 1897, reported that William Cathay had been actually masquerading as a woman for several years. According to the article, he had recently been found wandering around in a daze, and he claimed that an "Italian with a bear" was following him and trying to get him to dance with the animal. The man identified as Cathay was taken to Leadville, where he was judged "insane" as the local Herald Democrat smirked about how he took "care of his whiskers."

Williams was moved to a state asylum in April 1897, according to a 2009 article in the Pueblo Chieftain, which also verified that Williams' mother, Martha (believed to be pictured here), once worked at Pueblo's Lincoln Home in the early 1900s. (The Lincoln Home was an orphanage for Black children, according to the city of Pueblo.) Williams continued living in Pueblo until at least 1910, when she worked as a dressmaker for White & Davis, according to some sources.

Where and when did Cathay Williams die?

Where and when Cathay Williams, or William Cathay, died has remained a mystery for many years. A Findagrave memorial for her claims she died in 1892. The New Mexico Historic Women Marker Initiative is among those who believe Williams was running a boarding house in Raton, New Mexico, when she died in 1924. Other sources, including the National Park Service, have stated that where and when Williams died remains a mystery.

The puzzle about the end of Williams' life finally came full circle in early 2022, thanks to Pueblo librarian Rebecca Atkinson. In 2010, the Pueblo Chieftain reported that Atkinson had found new information about Williams, including the ledgers from Woodcroft Hospital. Using a Colorado Humanities grant, Atkinson was able to access what is now the Colorado Mental Health Institute records to find out more. Finally, Atkinson found what nobody else had ever uncovered: news of Williams' death in Pueblo in September of 1911. Atkinson believes Williams is buried in an unmarked grave in the "historic 1891 section" of Pueblo's Rosemont Cemetery.

Her posthumous honors

With Rebecca Atkinson's discovery about Cathay Williams' death in 1911, the long journey to finding her whole story has ended. Over the years, several authors, historians, and fans have written about or dedicated monuments to America's first and only female Buffalo Soldier. In 1999, biographer Linda Kirkpatrick wrote a poem about her. In 2012, poet Shane McCrae penned "The Ballad of Cathay Williams William Cathay." In addition, a monument at the Richard Allen Cultural Center & Museum in Leavenworth, Kansas, was dedicated to Williams in 2016. And in 2018, the WTVM reported that the National Infantry Museum in Columbus, Georgia, dedicated a bench to her.

Indeed, things are looking bright for keeping Williams' memory alive. In 2021, KRDO reported that the Trinidad History Museum dedicated a monument to Williams. In addition, modern Buffalo Soldier reenactor Haskell Hooks of Trinidad began a fundraiser to commission a statue of her. Also in 2021, Screenrant reported that Netflix's "The Harder They Fall" included a character based on Williams. Unfortunately, none of the tributes or articles about her include Atkinson's discovery yet, but hopefully it won't take long for them to catch up.