History's First Labor Strike Explained

Most people think the labor movement is a relatively recent historical phenomenon. History.com tells us that the first recorded labor strike in American history was in 1768, when journeymen tailors in New York walked off the job due to a wage reduction. Most people, however, associate the growth of labor with the establishment of the first large labor organizations of the late 19th century, such as the American Federation of Labor (AFL), and the great strikes of the period, including the Homestead Strike. The modernness of labor is reflected in the establishment of that annual celebration of workers, Labor Day, which Britannica tells us was first proposed only in the 19th century.

But labor history and its most notable tool, the strike, are much older than even 1768. For example, The Shoe and Leather Journal describes that in 1538, journeymen cobblers who wanted an advance on their wages went on strike in the town of Wisbech, England. Five centuries is a respectably long time, but it may come as a surprise to learn that the first labor strike is far older, dating to the 12th century B.C., in fact. It may be even more of a surprise to learn that this first strike occurred in one of the unlikeliest of places: ancient Egypt. Let's take a deep dive into the story of history's very first labor strike.

The strike occurred during Egypt's New Kingdom

It is important to understand the vast scope of ancient Egypt in history. Britannica explains how as a self-ruled kingdom under the pharaohs, ancient Egypt is usually dated from 2575 B.C. until 1075 B.C. This represents two and a half millennia of Egyptian history before the Roman emperors. Because of the time scale involved, the normal dating scheme for ancient Egyptian history while it was ruled by the pharaohs is to divide it into three parts: the Old Kingdom, the Middle Kingdom, and the New Kingdom.

History's first labor strike took place during the New Kingdom period, which dates from 1539 B.C. to 1075 B.C. This period was long after the construction of the famous pyramids, but it was an age of temple-building and extensive warfare. Sometimes the kingdom expanded its boundaries south and north, but at other times it was on the defensive against invaders who threatened to overrun the civilization. It was in this brew of invasion and monumental building projects that workers united for the first time in recorded history.

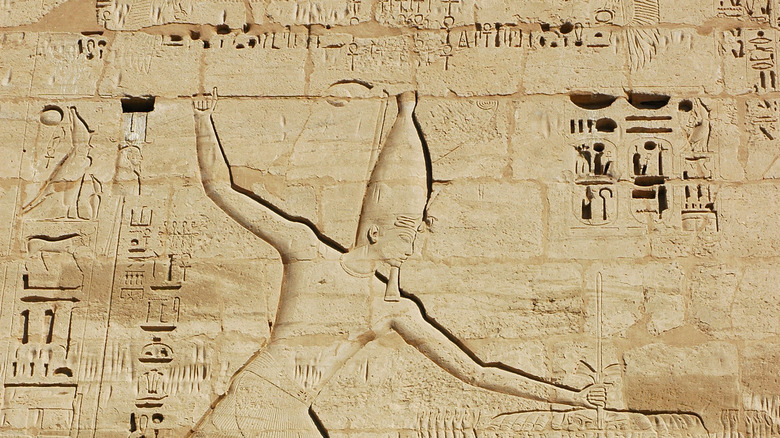

Ramses III

In 1187 B.C., Ramses III became pharaoh of Egypt. Britannica's outline of his career tells how his father, Setnakht, had established Egypt's 20th dynasty, and that his son sought to restore glory to Egypt. His role model was the more famous Ramses II, who was renowned for his militaristic exploits. Incidentally, these two Ramses were not related. Because Ramses III was a fanboy of Ramses II, he co-opted some of his predecessor's achievements and even etched them in stone in his own mortuary temple. It would be sort of like President Chester A. Arthur claiming on his burial tomb that he won the American Revolution and then issued the Emancipation Proclamation.

This has created some confusion on the part of Egyptologists who have tried to sort out what the latter Ramses actually did. In fact, he did quite a lot and played a key role in keeping together the kingdom during some critical wars. This alone has led to him being named the last great pharaoh of the New Kingdom. But it was these wars, and Ramses III's own desire to restore Egyptian glory, that ended up rebounding in the form of labor strikes.

The kingdom was beset by foes

In the beginning of Ramses III's reign, Egypt faced off against different enemies. Britannica relates how only five years after he assumed power, Egypt was attacked in the western Nile delta region by Libyan tribes. These the pharaoh defeated, but two years later the kingdom was assailed by the Sea Peoples. These were, according to the World History Encyclopedia, a coalition of various tribes of seaborn raiders who caused major disruptions at the end of the Bronze Age. Their depredations are partially responsible for the collapse of several civilizations of the time.

The Sea Peoples had sacked the Egyptian city of Kadesh then tried to invade the entire country. However, the pharaoh defeated them at the battle of Xios in 1178 B.C. Two years of peace followed before another war began with the Libyans, which Ramses III settled with the capture of their chief (per Britannica). Egypt was victorious, but it could no longer exert the imperial power it once had. However, with peace in hand, the pharaoh turned toward molding the land of Egypt through monumental — and expensive — building projects.

Ramses III was a big spender

Ramses III contributed to some very well-known ancient Egyptian sites. Britannica explains that he constructed a mortuary temple for himself (Egyptian rulers were big into building their own tombs while alive) and expanded the Temple of Karnak. This all strained the Egyptian economy. The World History Encyclopedia concludes that the wars that had plagued the early part of the pharaoh's reign probably resulted in not only the financial burdens a war brings but also a significant loss of potential laborers. Harvests had taken weather-related hits, and foreign trade lagged after the conflict with the Sea Peoples, all contributing to a general decline in artisanship. As a result, Ramses III's penchant for restoring pharaonic glory and all its trappings would have strained resources and drained Egypt's coffers. The pharaoh launched military and trading missions that, while successful, did not quite bring in the wealth he would have hoped for. (Historians believe a good deal of the incoming cash might have been siphoned off by corrupt officials.) As Ramses III entered the latter part of his reign, it was clear that despite his pretensions of glory, the economic woes of Egypt were deep.

Still, as the pharaoh neared the 30th anniversary of his reign, he started to plan a monumental jubilee. The World History Encyclopedia explains that this party was to go all-out. No expense would be spared. If anyone advised pharaoh that the country was pasting papyrus over a crisis, he ignored them.

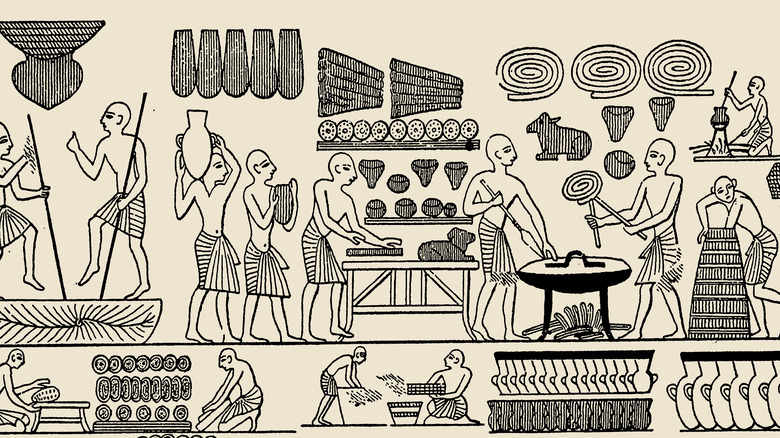

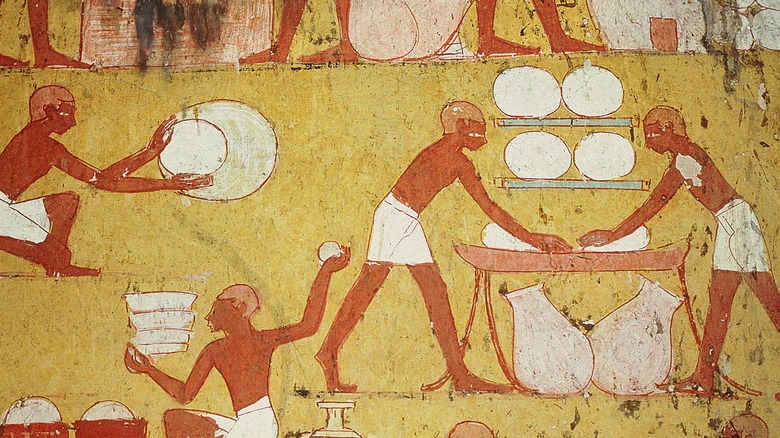

Wages were food in ancient Egypt

It is important to emphasize that ancient Egypt did not have a modern economy. The World History Encyclopedia reports that Egypt did not have coinage but operated as a huge barter system. They used a unit called a deben which assigned values to things, but without using cash. Thus, if it was agreed that a jug of beer was worth two debens and your pair of sandals was worth one deben, then two pairs of sandals were worth one jug of beer. It is in this way that almost anything could be used to trade providing it had an agreed-upon value. Taxes were collected in the same way through the collection of stuff rather than coin.

Normally, goods were paid for using wheat, barley, and oil. Even if the seller had enough of their own oil, they would still accept it as payment because in that economy, they could turn around and trade the oil for something else. Workers were paid with stuff, too, mainly bread and beer. The Accounting Historians Journal notes that the economy was centralized on storehouses of grain. Thus, those who were working on projects for pharaoh, such as preparing for a large jubilee, would be paid using the grain that the Egyptian state had banked. And this was a problem for a kingdom that was struggling with low grain harvests.

Lagged wages were the primary cause

In 1159 B.C., artisan workers were in full swing at Set-Ma'at, which is translated by the World History Encyclopedia as the "place of truth" near the city of Thebes. Set-Ma'at, which is better known today as Deir el-Medina, was a town built specifically to house the artisans who constructed and worked on the monumental tombs in the Valley of the Kings and Valley of the Queens. It is an important site today for Egyptologists since archaeological findings at Deir el-Medina have provided great insight into Egyptian daily life.

The densely packed town was unique among Egyptian settlements in that its inhabitants could not independently provide for themselves. Everything was brought in. It is also important to note that these workers were not enslaved, nor were they, according to "Intermediate Elites in Pre-Columbian States and Empires," a part of the forced labor gangs under the so-called corvée system in which Egyptians were compelled to work as a type of taxation. The people at Deirel-Medina were employed directly by the state because of their craftsmanship and were honored among the working classes.

It is because of their narrow skill set that Set-Ma'at was completely dependent upon imported goods. This included grain wages, which amounted to rations. Unfortunately, in 1159 B.C., with the storehouses low on grain, shipments of these rations were delayed. Papyrus Stories describes how at Set-Ma'at, the shipments were delayed by 20 days. Since money equated with food, this was a serious problem.

Nobody took corrective action

The immediate crisis was dealt with in an ad hoc situation. According to the Journal of Near Eastern Studies, the scribe Amennakht took the matter of the delayed grain into his own hands. Amennakht is largely unknown in history, and the name appears multiple times in Egypt's archaeological record ascribed to different people. Regardless, this particular Amennakht took on the role of a union representative. He went to the mortuary temple of Harmhab. There, he was able to procure 46 bushels of emmer wheat. This averted the immediate crisis, but the root of the problem was not addressed. As the World History Encyclopedia points out, instead of trying to figure out how to effectively get grain payments to the artisans, the government redoubled its efforts for jubilee preparations.

Predictably, grain payments were delayed again. This time, after a delay of 18 days, the workers declared, "We are hungry!" They then refused to work. The first recorded strike in history had begun.

The workers staged a sit-in

The striking workers were well ahead of their day in terms of protest innovations. They invented the sit-in. Papyrus Stories describes how the workers first went to the Temple of Thutmosis III, where they sat in peaceful protest. Meanwhile, two police, two foremen, and two deputies came to them. These officials shouted at them to "Go back, then." To this, the striking workers responded that they had a matter to take up with the pharaoh. When evening came, they went to the necropolis.

The record after this point grows spotty due to damage in the original papyrus, but it is seen that the complaints of the workers were heard by an official. This is translated in Journal of Near Eastern Studies, which relates that the workers said, "It was because of hunger and because of thirst that we came here. There is no clothing, no ointment, no fish, no vegetables. Send to Pharaoh our good lord about it, and send to the vizier our superior, that sustenance may be made for us." As a result, the rations for the month were released. Still, the root causes of the problem again went unaddressed, and the workers were beginning to feel emboldened.

Workers blockaded the Valley of the Kings

Further grain shortages resorted in more complaints and demonstrations. The complaints also started to change. Two workers, named Kenena and Hay, are reported by Papyrus Stories to have said to an official who told them to go back to work, "We will not return, tell your superiors! Truly, it was not because we hungered that we passed (the walls). We have an important statement to make. Truly, evil is done in this place of Pharaoh!"

This time, the Journal of Near Eastern Studies tells us, the vizier explained that the granaries were mainly empty and instead gave them a half-ration. This was clearly not enough, so shortly after they went on strike again. This time they went to the Temple of Merenptah, where they complained to the mayor. The mayor sent Mennefer, gardener of the Chief Overseer of Cattle. He gave them 50 bushels of emmer wheat to placate them.

Yet this did not resolve the problem. The World History Encyclopedia relates how the workers ended up blocking access to the Valley of the Kings. This was serious stuff since it meant priests, much less descendants, could no longer give offerings to their dead ancestors. Officials threatened to remove them by force, but a worker promised to damage a royal tomb if they tried.

Officials were so perplexed they gave everyone pastries

What the workers did at Set-Ma'at was truly unprecedented. Egypt was a dictatorial state where the pharaoh was in essence a living god. Artisans were disrupting ma'at, which the Egyptian Museum explains is the concept of universal order, harmony, and balance, which was sometimes personified as a goddess. Ma'at was an ingrained ethical and moral tenet of Egyptian civilization, and everyone was expected to adhere to it. The World History Encyclopedia explains it was for this reason that the striking workers perplexed authorities, since it was completely alien behavior. Workers were expected to work and not challenge authority. Meanwhile, the artisans saw it from the opposite side of the lens. Pharaoh was supposed to follow ma'at as well, which meant that he needed to provide for them or at least ensure that his minions did.

The authorities were so confused as to what to do that at one point they even ordered pastries for the striking workers in the hopes that this would make them go back to work. This did not work. In fact, workers broke into the granary of the Ramesseum, the main grain bank for Thebes, the next day.

The pharaoh may not have known about the strike

The strike took on a life of its own. The World History Encyclopedia notes that as time went by, the strikers' issue became more about violations of ma'at than late payments. For the next three years, the workers would routinely go on strike every time their payments were late. It is a bit puzzling as to why the government, being as it was a monarchy, did not simply crush the protesting artisans.

The answer seems to be that the local government kept the whole affair under wraps. For their part, if they sent word to Ramses III that the artisans weren't working, it would look like the officials weren't doing their jobs. This could result not just in the execution of the workers but of the local authorities as well. They needed to keep them working so that the pharaoh could have his jubilee and maintain his own divine status. Evidence that the pharaoh and his court may not have even known of these happenings is that the vizier came to Thebes to gather statues for the jubilee, but there is no hint that he knew workers were striking. Instead, it seems that the strikes were dealt with by local authorities as grains were made available to placate them, and that some sort of settlement was eventually reached.

The strikes were consequential

It is surprising, but the World History Encyclopedia tells us that the jubilee was held in 1156 B.C. and went off without a hitch. Ramses III, however, would not enjoy another year. As Britannica relates, he was assassinated in an attempted coup d'etat that left him with a knife wound to the throat.

By this time, the strikes at Set-Ma'at had made a lasting impact. Artisans were an honored class who brought allegations of corruption against the government. Also, while there are no detailed narratives of later Egyptian strikes, records do show they occurred. Workers had been empowered. Meanwhile, the World History Encyclopedia reports that some Egyptologists use this strike to date the beginning of the decline of the New Kingdom, which fell a century later. With the strikes, the old mores of Egyptian concepts of an orderly universe were called into question. While the strikes at Set Ma'at were no revolution, they may have been the start of a longer-term discrediting of the New Kingdom and pharaonic Egypt.