Psychiatrist Said The Hillside Strangler's Multiple Personality Claims Were Bogus

As new medical and mental diagnoses are discovered, they sometimes become pop-culture trends. As strange as it is that diseases such as tuberculosis inspired fashion trends (per Smithsonian Magazine), we are not immune to these influences in modern times. From the 1960s to '90s, there was a public obsession with multiple personality disorder (MPD) or dissociative identity disorder (via Healthy Place). Books and movies like "Sybil" and "The Three Faces of Eve" launched this rare and under-researched condition into common parlance by the 1970s (via The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease). Not immune to social popularity and the acclaim of being associated with an MPD case, psychotherapists fueled the trend with a staggering increase in diagnoses.

If an individual's psychological makeup has the potential to contain multitudes of personalities, then what happens when just one of those personalities commits a crime? In the late 1970s, one of the decade's most notorious killers attempted to pin his crimes on another version of himself.

The Hillside Stranglers, plus one

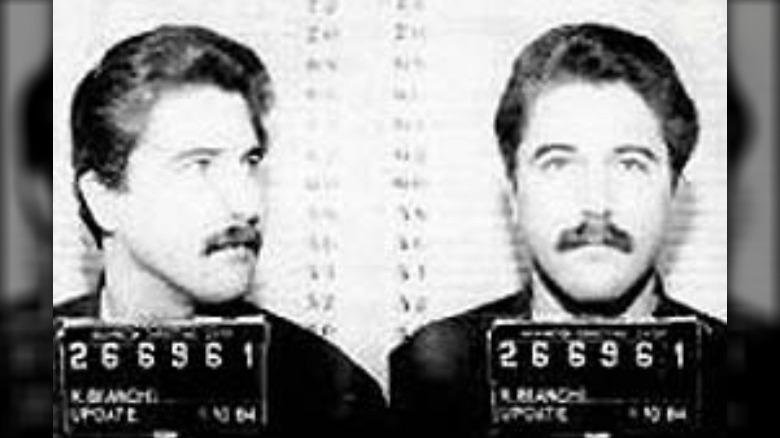

In the late 1970s a number of young women were found raped, killed, and strewn on the hills and roadsides of southern California (via "Serial Killers: The Method and Madness of Monsters"). The gruesome work was dubbed that of The Hillside Strangler. But this was in fact the work of two men, Kenneth Bianchi (above) and his cousin Angelo Buono.

After committing their California murders, Bianchi moved away from his cousin and partner-in-murder to upper Washington State. He attempted to join the Bellingham police force but failed, settling for a job as a security guard (via History).

When Bianchi was captured in association with the murder of two Washington State women, the similarity between the Washington murders and the Hillside Strangler murders quickly led authorities to connect the cases. Bianchi turned over his cousin Angelo Buono as his accomplice and they became The Hillside Stranglers. It wasn't until Bianchi found himself incarcerated in a Washington State jail that he told anyone about "Steve."

Encouraged to plead insanity

Bianchi described how a meeting with his attorney Dean Brett "scared me straight" (via "Serial Killers: Up Close and Personal"). Brett made sure to describe in explicit detail exactly how hangings by the state sometimes go wrong. Though the exact dialogue lies behind the door of attorney-client privilege, Bianchi was encouraged to come up with some explanations for his actions. Then Brett suggested that Bianchi should plead not guilty by reason of insanity to avoid the death penalty.

Perhaps Bianchi's former interest in becoming a member of the force ingratiated him with the Bellingham officers. While being held for the crime of killing two women and potentially more, Bianchi was allowed access to unsupervised activities including watching "The Three Faces of Eve" and the movie version of "Sybil" (via "Serial Killers: Up Close and Personal").

Bianchi claimed that "Steve," an alternate and violent personality, was responsible for the crimes. With the help of his attorney, Bianchi claimed he was mentally ill, suffering from MPD. Lacking any shred of creativity, as well as basic morality, the name "Steve" was likely borrowed from the psychology student Steve Walker, whose degree and resume Bianchi had previous attempted to pass as his own, years before (via "Serial Killers: The Method and Madness of Monsters").

The right doctor for the diagnosis

Trying to determine mental condition or malingering, Los Angeles County Superior Court judge Ronald M. George ordered a total of six psychiatrists and researchers to interview Bianchi. One of those left unconvinced of Bianchi's claim was renowned researcher Dr. Martin Orne.

Orne dedicated much of his career to the study of hypnosis (via The New York Times), a tool often used by psychiatrists to explore the various personalities in MPD. He also pioneered the study of demand characteristics. These are the authority-pleasing behaviors displayed by participants or patients. It's sometimes called the good subject or the Orne effect (per Psychology Dictionary). Essentially, someone participating in a study tries to figure out what the researcher wants, and then tries to supply that, rather than reacting honestly.

Orne interviewed Bianchi a number of times, sometimes using hypnosis (via The New York Times). It was during one of these sessions that Bianchi unknowingly revealed his charade.

Fraud is exposed

While under hypnosis, Orne introduced Bianchi to an imaginary person in the room, and Bianchi responded by reaching his hand out to shake that of the stranger's. The expert immediately recognized that Bianchi was faking. People in a hypnotic state never physically interact with hallucinated people or objects (via the May 1984 issue of the International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Hypnosis).

The New York Times reported that Dr. Orne was a longtime advocate of the use of hypnosis, but was also a staunch critic of its use, especially in courtroom settings. Additional aspects of Bianchi's disorder convinced Orne that Bianchi was a fraud. No one who had known Bianchi had ever witnessed him exhibiting the symptoms of MPD. The amateur way in which Bianchi portrayed his various personalities and the weakness he claimed he had to suggestion, indicated the Orne effect. That, as well as a long history of deception and violence, convinced the expert that Bianchi had antisocial personality disorder, not MPD.

The end of the lies

Orne provided the evidence needed to prove that Bianchi lied about his MPD in an attempt to escape prosecution for his crimes (via International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Hypnosis). Though other examining psychiatrists remained convinced of the diagnosis, Orne's testimony and credentials convinced Judge Ronald George that Bianchi had faked his MPD (via the Los Angeles Times).

Once his lie crumbled, Bianchi pled guilty to avoid the death penalty and testified against Buono (via Democrat and Chronicle). This took up six months of the court's time with Bianchi constantly recanting his previous statements. He claimed that "it wasn't until the hypnosis was used that I came to believe I committed the crimes and that these new memories developed." Bianchi was sentenced to life in prison for raping, torturing, and murdering 10 young women with his cousin (via History). Although Orne believed that hypnosis could be "a valuable therapeutic tool," he was also extremely critical of its use in court (via the Los Angeles Times). Ultimately, his work led to limiting the use of hypnosis in criminal investigations (per The New York Times). Dr. Orne died in 2000 at the age of 72.