How The Murder Of Stanford White Became The Trial Of The Century

On June 26, 1906, millionaires Harry Thaw and architect Stanford White sat down separately to watch a performance at the Beaux Arts Madison Square Garden, a precursor building to today's Madison Square Garden.

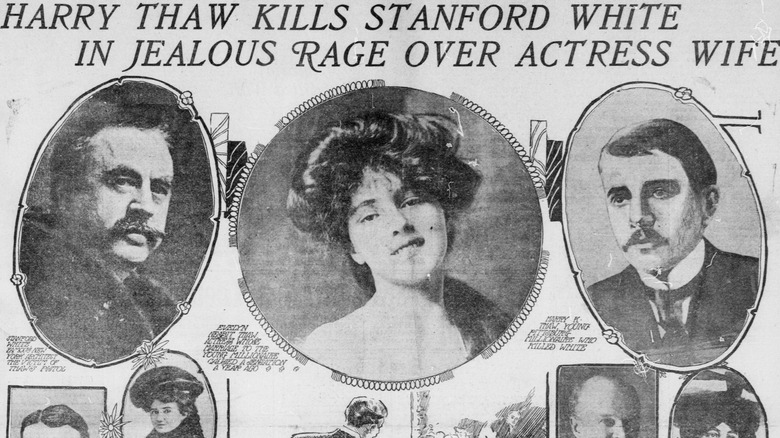

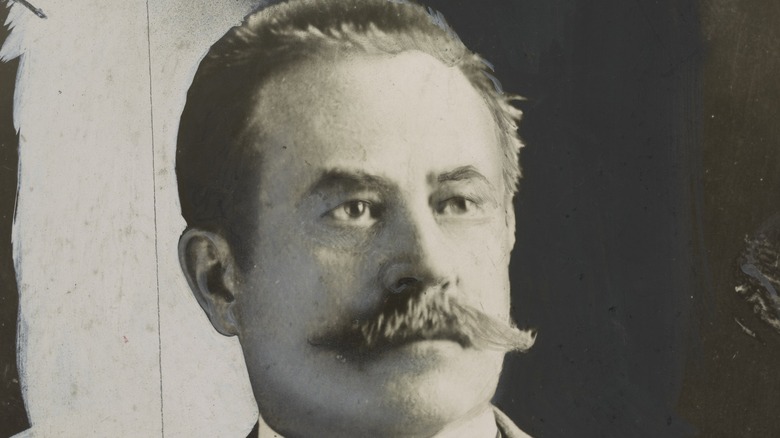

As Avenue Magazine details, upon seeing White, Harry Thaw was filled with contempt, knowing White to be the man who sexually assaulted his wife, actress Evelyn Nesbit Thaw, while White was acting as a benefactor of her early stage career when she was a 16-year-old girl. White's reputation of disturbing sexual misconduct was an open secret, with esteemed author Mark Twain noting at the time of the Harry Thaw murder trial that White had a history of "eagerly and diligently and ravenously and remorselessly hunting young girls to their destruction."

Harry walked up with little hesitation and fired three rounds from his pistol point blank towards White's skull, instantly killing the man who had raped his wife. White met his end amongst the opulence of a building he himself had designed. Even more poetic, the serial sexual predator died as the number "I Could Love a Million Girls" played on stage.

The story was thrilling to the public. The openness of the crime, the details of White's death, and the background and character of the Thaws became intensely covered by the media.

Coverage of the trial reached national scale

Media coverage for the Harry Thaw murder trial reached national scale news almost immediately after the death of Stanford White. According to the Library of Congress, newspapers from New York to Salt Lake City and from Washington, D.C. to San Francisco published pieces about the killing within a day of the murder on top of the rooftop garden seating of Beaux Arts Madison Square Garden.

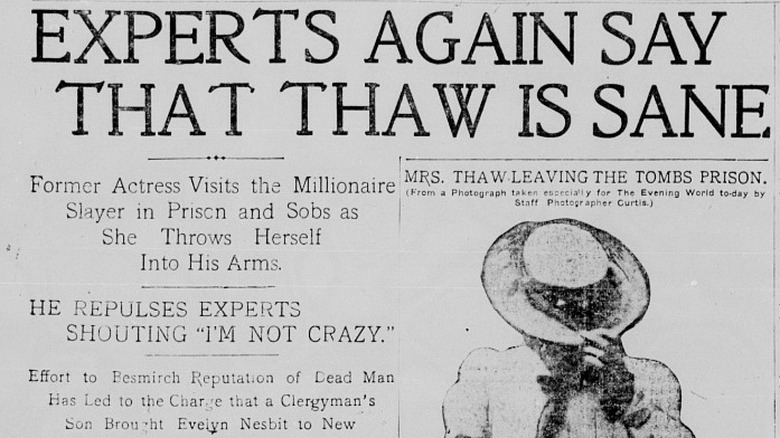

Intense national coverage of the trial did not end soon after Thaw's arrest and incareration into a mental institution, and the trial stayed in the national consciousness for around two years, with newspaper editions across the country mentioning the Thaw trial from 1907 to 1909, according to a search of the Library of Congress' archives of American newspapers.

Headlines were attention grabbing, drawing readers with details like "Irresistable Impulse Goaded Thaw to Slay" or "Thaw Taken to Madhouse Vigorously Protesting."

Nowhere was the public frenzy made clearer than Pittsburgh, the city where Harry Thaw was most well known as the son of wealthy railroad baron William Thaw. The scene in Pittsburgh is described in a February 1, 1908, edition of The World, which reported, "thousands of persons were on the thoroughfares, newsboys were almost mobbed by excited purchasers," after the verdict declared Thaw not guilty due to insanity.

There was no question as to what happened

The murder of Stanford White did not capture the ears and hearts of the public because of any degree of mystery. To the contrary, Harry Thaw admitted to the murder immediately, clearly explaining that he had shot Stanford White, that he did so because White assaulted his wife, and that he did not regret his actions, as per the June 26, 1906, edition of The Washington Times. In addition, the newspaper reported on rumors that, around that time, Thaw made a habit of walking about the New York socialite scene armed and had spoken to others about killing White.

Thaw also admitted to his motive, reported to have said of his wife's reaction to seeing White in the theater: "That poor, delicate little thing, all nervous and shaking like a reed, and there he was, the big healthy scoundrel. God! This man ruined my wife! He won't do this any more, or ruin any more homes. White deserved all he got."

Thaw was so straightforward about his killing of White that newspapers labeled him a murderer even before the result of the trial. Headlines did not bother to refer to the death of White as an "alleged" or "suspected" murder despite presumption of innocence being the law of the land since over a decade prior in the 1895 Supreme Court decision Coffin et al. v. United States.

The plea of insanity seemed shaky

From the initial reporting after Harry Thaw's arrest, it was clear that the argument of insanity would be Thaw's primary defense. With the events of that night being so clear, the millionaire coal and railroad heir needed some defense to keep his freedom, and insanity was the idea that stuck.

The night that Stanford White was shot, the second page of the The Washington Times contained an interview of one of Thaw's close friends, who gave his opinion on Thaw's alleged insanity. Burr McIntosh was interviewed the night White was killed, and he insisted that "Thaw must have been insane when he shot White, I don't understand otherwise how he could have done the shooting ... There was nothing about his conduct when I saw him that indicated in the slightest the coming tragedy."

While far from an expert opinion, and riddled with bias, McIntosh's opinion published the night of the killing set the idea in motion of Thaw being "insane." This theory was further explored by psychiatrists who visited Thaw the following night while he was being held in jail. The June 27, 1906, issue of The San Francisco Call reported on Thaw's initial psychiatric evaluation, reporting that several doctors saw Thaw, with one going on record to say he believed Thaw was emotionally unstable.

Insanity was not a clear cut legal or medical concept at the time

In the early 1900s, there was no commonly agreed upon definition of the term "insanity," yet it was still a widely used criminal defense. In 1909, experts attempted to solidify a framework for insanity when the American Institute of Criminal Law and Criminology organized its committee on Insanity and Criminal Responsibility.

A review published in The Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry describes this disagreement, noting that lawyers and physicians went round and round about what they meant by the term, never fully agreeing but still drafing legislation.

The prosecution gained a slight legal advantage from Harry Thaw's defense of insanity since insanity is an "affirmative defense" where the defense is left with the burden of proof. The prosecution took advantage of this burden in Thaw's trial by mercilessly cross examining defense experts on their lack of familiarity with the broad and wide-reaching methods of testing insanity at the time, making it difficult for the defense to prove any one definition soundly.

The Los Angeles Herald issue published on February 6, 1907, reported on the district attorney's cross examination of a doctor claiming to be an expert on insanity, describing his relentless questioning of the witness, who seemed to get confused when asked to back up his opinion with scientific research and experience. The newspaper reported that the doctor repeatedly hesitated and evaded questions.

There were mixed opinions on the victim

Papers at the time were especially interested in publishing opinions of those close to the case: friends of the victim and defendant, members of the family, or anyone with any proximity to the murder. Early reporting included positive accounts from many of Stanford White's acquaintances and business partners who demonized Harry Thaw.

Defense of White came a day after his death in The San Francisco Call, where George Lederer, a well-known theater manager and friend of White, called Harry Thaw a degenerate. Lederer also defended White's actions with Harry Thaw's wife, Evelynn Nesbit Thaw, saying that White's conduct with her was nothing but polite and gentlemanly.

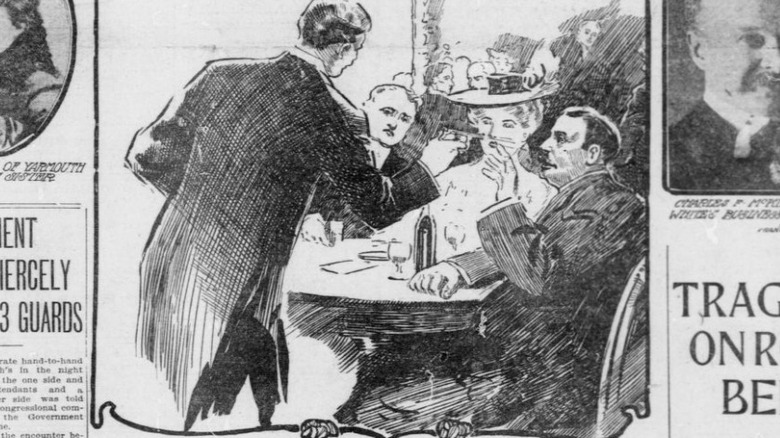

Denial that White had raped Evelyn Nesbit Thaw, and further defense of his character, was common in the press at the time. An evening edition of The World on June 27, 1906, came to White's defense as well, publishing an interview with an attorney who stated that White generously donated to the Nesbit family. The paper also published a scrawling cartoon that illustrated Evelyn's rise to theatrical fame, attributing her success to White's financial contributions.

Public opinion did not share this perspective on White, seeing him much the same way he is known today, as a man with a history of sexual misconduct and assault. As such, when Harry Thaw was being arrested for White's murder, it was reported by The Washington Times that many shook his hand and thanked him for his actions.

The coverage focused on relationships and personal history, not law or facts

Since Harry Thaw had admitted to killing Stanford White, and since he had shot him in public view, there was not much debate or speculation in the papers about the facts of the case. The Thaw trial was not a popular event because of any degree of mystery, but because the public found the characters and their motivations compelling.

One such example is found in the June 27, 1906, issue of The World, which published a cartoon across the third page of the paper detailing the history of Harry Thaw and Evelyn Nesbit Thaw. Only two frames of this eight section cartoon included the actual events of the shooting; instead, the paper decided to focus on the Thaw's marriage, Evelyn's rejection and eventual acceptance in high society, and Harry Thaw's mother's poor reaction to the marriage.

News stories were focused on personal opinions from friends and family of Harry Thaw and White; even the whereabouts of Thaw's mother were reported on in The Washington Times. They were especially concerned with each character's standing in high society, with The Washington Times reporting the night of the murder explaining Harry Thaw's rise in high society, detailing the expensive dinner parties he had hosted.

Every moment was documented

From the moment of the shooting, the actions of Harry Thaw and his wife Evelyn Nesbit Thaw were documented by reporters and relayed to the public. Descriptions as specific as when exactly Harry Thaw was handcuffed, how and when he raised his arms up, and what buildings he passed and entered during his arrest were reported.

No detail was too mundane, from sitting down to lighting a cigarette. The Washington Times set the scene of Harry's arrest accordingly, describing Thaw's dramatic entrance into the police station, where he promptly and arrogantly smoked a cigarette. They even described how he promptly took a nap after some initial questioning.

Evelyn faced similar media coverage the night of the shooting, with Times reporters covering her attempts to find the right building where her husband was being held and being directed to the correct court location.

These actions were also reported on in detail in subsequent issues and lifted verbatim by other contemporaneous papers. For example, the Salt Lake Herald found details of Thaw's arrest equally compelling, printing the same details directly copied from the story in The Washington Times.

Evelyn Nesbit Thaw was seen as a compellingly sympathetic character

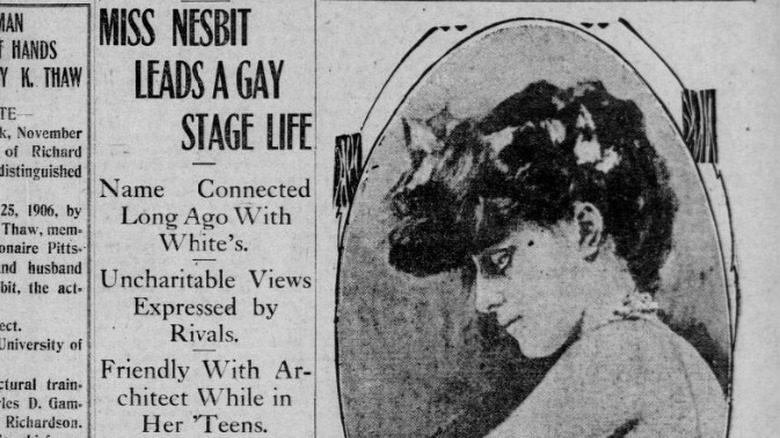

Evelyn Nesbit Thaw's story was firmly within the media's lens, not just for her proximity to her husband but for her own story of rising through society's ranks. Papers from across the country committed sections of coverage specifically to Evelyn's history and background. The San Francisco Call dedicated a front page column to her stage career. The Evening World printed glamorous illustrations depicting her social rise, and The Washington Times covered how her mother-in-law initially objected to her marriage to Harry Thaw.

Sympathies towards Evelyn increased as the investigation continued. The Paducah Evening Sun reported on June 29, 1906, that during the prosecution's grand jury inquest, she was allowed to evade most questions due to her distress, often answering each of the state's questions with a variation of "that is too painful to discuss."

As the trial process moved on, Evelyn became the primary witness for her husband's defense, with her attorneys telling the Los Angeles Herald that her "revelations will open the eyes of New Yorkers." She won the sympathies of the jury when she shared her victimization as a child at the hands of the murder victim.

Eyes were on Evelyn not just on the witness stand, but as she comforted and supported her husband through the proceedings, leading The Washington Times to portray her in a sketch that included a pattern reminiscent of a halo behind her head, firmly planting her in the public's consciousness as the hero amidst the tragedy.

The first trial ended with a hung jury

According to the Library of Congress, Harry Thaw's first trial began on January 23, 1907, about seven months after the shooting occurred on June 26, 1906. The prosecution's case continued into the first week of February before resting.

On February 7, 1907, the defense called their star witness, Evelyn Nesbit Thaw, who spoke of her rape at the hands of the murder victim, Stanford White. As described by Avenue Magazine, Evelyn detailed how White had drugged her champagne, and how she was assaulted in her sleep after she passed out.

As the Library of Congress notes, the jury was deadlocked, with The Times Dispatch reporting on April 13, 1907, that, after nearly 48 hours of deliberation, five jury members were in favor of acquittal while seven jury voted for the death penalty. They were then dismissed, and a new trial was scheduled.

The inconclusive verdict was reported as a shock, with Thaw reportedly sinking in his chair when the jury stated they had not reached a decision. His wife was reported to have responded with emphatic anger when told that seven of the 12 jurors voted in favor of execution.

The defense amended their plea for the second trial

The second trial began January 9, 1908 (via the Library of Congress), with the defense adopting a narrower strategy. While insanity was always Harry Thaw's primary defense, his legal team decided to make it their sole focus, amending their plea to specifically not guilty on the grounds of insanity, as reported by the January 7, 1908, issue of The San Francisco Call.

The defense was focused on the words of the jurors who voted in favor of acquittal in the first trial. Of the five jurors who had voted for acquittal, four of them said that they did so because they were convinced that there was reasonable doubt as to Thaw's sanity, as reported in The Times Dispatch. The hope in the second trial was that their theory of insanity could convince new jurors for the second trial.

In the end, the defense's theory of "dementia Americana," or the idea that Thaw had a temporary bout of emotional insanity upon hearing about his wife's rape at the hands of Stanford White, won the day, but at the cost of committing Thaw to a mental facility.

The media was obsessed with shallow details

Every physical detail of those involved in the case was reported on. A February 10, 1907, edition of The Washington Times featured a full length portrait sketch of Evelyn Nesbit Thaw on the front page and a detailed physical description of her that by today's standards would come across as personally invasive. The column mentioned her weight, descriptions of her eyes and hair, and wrote that she had a rather enigmatic smile.

While Evelyn was a large focus, with later editions closely following her choices for court attire, Harry Thaw's physical form was also closely analyzed by journalists at the time. Before the start of the second trial, Thaw's physical form was closely scrutinized by journalists in the January 7, 1907, issue of The San Francisco Call. The front page feature noted that he looked sallow, with an unhealthy pallor to his skin, puffy cheeks, gaunt appearance and weight, and a nervousness about him.

Even the district attorney trying the case was not exempt from the press passing judgment on his physical character, with the same article describing him as healthy and in good spirits, clearly not affected by the trial but, instead, rather confident.

A flurry of excitement followed the final verdict

A range of reactions were reported immediately following the verdict. For Harry Thaw, he initially grinned with "positive satisfaction," as reported by The Evening World, but then began to behave violently as it was explained that he would be committed to Matteawan mental facility. His attorneys immediately petitioned for an appeal, arguing that commitment to Matteawan was unconstitutional. They would ultimately be unsuccessful.

The failure of the appeal was unsurprising, as even Harry Thaw's attorney seemed to believe he should be committed to asylum. The Evening World reported that he agreed with the district attorney that a just verdict was reached, with the paper specifically reporting that his attitude and demeanor indicated his support of the final decision — even going so far as to unofficially agree it was in his best interest to be committed.

Theodore Roosevelt Pell, a relative of President Theodore Roosevelt and member of the gallery, was especially pleased with the verdict — he even applauded the verdict and was held in contempt of court for misconduct, with the judge shutting down his ruckus and having him fined $25 after just three claps.

Harry Thaw required protection as he exited the courthouse and headed towards the train station as crowds cheered at the result of the trial. As Encyclopedia notes, Harry Thaw spent the rest of his life in various institutions after divorcing Evelyn Nesbit Thaw in 1915, and he even garnered a few more headlines for other criminal activity.