Pope Francis' Apology To Canada's Indigenous Peoples Explained

Pope Francis made history on Monday, July 25, when he publicly apologized for the Catholic Church's role in creating and overseeing the federally funded, church-run residential school system of Canada. That system officially ran from 1883 until the last school was closed in 1997. The purpose of the schools, per the Indigenous Peoples Atlas of Canada, was to force Indigenous children to assimilate into white Canadian culture and leave behind their languages, customs, and cultural and religious practices. The schools were just one part of the Canadian government's "aggressive assimilation" plans to subvert and colonize Indigenous Peoples and their territories.

Over 150,000 First Nations, Métis, and Inuit children were taken away from their families and forced to attend the boarding schools. The schools were modeled after similar programs in the United States and British colonies that sought to overcome the perceived threat of Indigenous Peoples to the so-called progress of new nations under colonization. Per AP News, 66 of Canada's 139 residential schools were run by Catholic religious orders; the CBC puts that number at closer to 75%.

Indigenous schools were responsible for cultural genocide

Survivors of Canada's residential schools have reported that they were abused physically and sexually and neglected as students. As reported by CBC News, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada spent over six years interviewing more than 6,000 people who had attended the schools, as well as their family members. They released a report in 2015, which included 94 recommendations as to how the Canadian government could respond to its findings.

Chair of the Commission Justice Murray Sinclair called the schools' acts "cultural genocide" and noted that for seven generations of Indigenous Peoples, "Survivors were stripped of the ability to answer these questions, but they were also stripped of the love of their families. They were stripped of their self-respect and they were stripped of their identity." Commissioner Marie Williams spoke to the fact that at least 3,200 children never came home from the schools; a third of those children's names were not recorded and half have no record of their cause of death.

Sinclair later spoke on the CBC Radio programs "Power & Politics" and "The House" and estimated that the number of children who died within the residential school system was closer to 6,000, per CBC News, noting, "We think that we have not uncovered anywhere near what the total would be because the record keeping around that question was very poor."

Calls for apologies from the pope date back several years

Among its recommendations, the Commission specifically called upon the pope to travel to Canada and deliver an apology in person within a year. In 2009, per CBC News, Pope Benedict XVI invited a delegation from Canada's Assembly of First Nations to the Vatican for a private meeting. There, he spoke of his "sorrow" over the abuse endured by generations of Indigenous Peoples but stopped short of apologizing for the Catholic Church's role in the abuse and genocide. The Anglican church, the Presbyterian church, and the United church apologized for their respective complicity in 1993, 1995, and 1998. No apology came from the Catholic Church for several years.

Beginning in May 2021, over 1,308 unmarked graves were discovered near the sites of former residential schools — 215 in Kamloops, British Columbia; 182 in Cranbrook, British Columbia; 751 in Marieval, Saskatchewan; and more than 160 on Penelakut Island, British Columbia, as reported by the Ottawa Citizen. The world reacted in shock and horror and the terrible history of Canada's residential schools was once again brought to the forefront.

Unmarked graves remind the world of shameful Canadian history

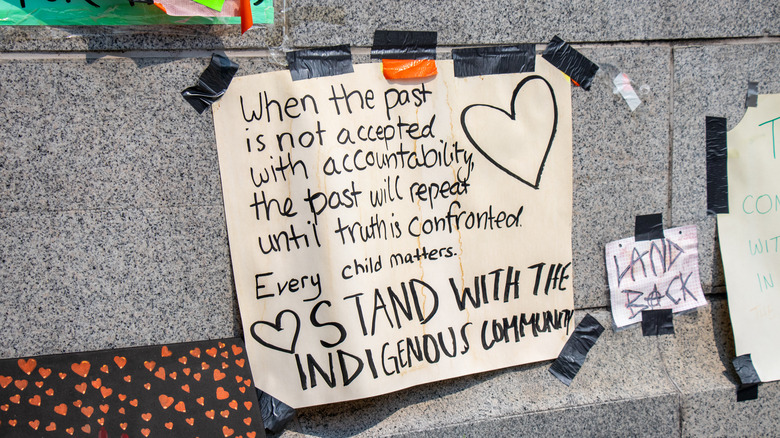

Per the Ottawa Citizen, it's unclear whether or not the bodies found in the unmarked graves are those of children who attended residential schools. Leaders from ʔaq̓am, a band within the Ktunaxa Nation who discovered the 182 graves in Cranbook, released a statement in which they emphasized that it was "extremely difficult to establish whether or not these unmarked graves contain the remains of children who attended the St. Eugene Residential School." However, it is a strong possibility. The Department of Indian Affairs notoriously refused to ship home the bodies of students who died while at school, citing prohibitive costs. The unmarked graves were discovered via ground-penetrating radar surveys. Memorials to children who never returned home from the boarding schools appeared around Canada, often using pairs of shoes to represent the missing children, as shown above.

Murray Sinclair spoke to the CBC Radio show "The Current" on June 1 and told the host he'd received over 400 calls in the days after the discoveries, reporting, "I've spent most of the last three or four days on the phone with survivors who call me because they're so emotionally distraught at the revelation." Sinclair went on to say that despite his past estimate of 6,000 children dying while attending residential schools, he now thought the number "could be in the 15,000-25,000 range, and maybe even more," adding, "I suspect, quite frankly, that every school had a burial site."

Pope Francis apologizes at the Vatican

On July 25, Pope Francis began what he called a week-long "penitent pilgrimage" to Canada, as reported by the Associated Press. "I am deeply sorry," he announced to people gathered in Edmonton, Alberta at the site of a former residential school. "I humbly beg forgiveness for the evil committed by so many Christians against the Indigenous peoples." His visit and his words came 15 years after the Canadian government implemented the Indian Residential Schools Settlement Agreement and seven years after the Reconciliation Commission called for the pope to travel to Canada to officially apologize for members of the Catholic Church's role in the schools' abuse and genocide. The pope went on to travel to four Cree lands to pray at cemeteries and publicly apologize.

Four Indigenous chiefs accompanied Francis to a site near the old Ermineskin Indian Residential School and placed a ceremonial feather headdress on his head at the conclusion of his speech, declaring him to be an honorary community leader. Francis' visit to Canada follows a spring 2022 meeting at the Vatican with several tribal leaders representing the First Nations, Metis, and Inuit. The pope also offered an apology at that meeting, but promised to repeat his apologies in Canada itself.

Will action follow Pope Francis' apology to Canada's Indigenous Peoples?

The Associated Press spoke with various people who attended Pope Francis' assemblies, including several leaders and members of Canada's many Indigenous nations. Former Chief of the Assembly of First Nations Phil Fontaine, who is also a survivor of a residential school, told the AP: "It was an achievement on the part of the Indigenous community to convince Pope Francis to come to a First Nation community and humble himself before survivors in the way he did today. It was special. And I know that it meant a lot to a lot of people."

Chief Tony Alexis of the Alexis Nakota Sioux Nation said Francis' apology "was validation that this really happened" but noted that action was also important and the pope "can't just say sorry and walk away." Evelyn Korkmaz, another survivor of a residential school, told reporters, "I've waited 50 years for this apology, and finally today I heard it." Korkmaz also expressed a desire for something more, adding, "I was hoping to hear some kind of work plan" that would lay out concrete actions by representatives of the Catholic Church in terms of accountability.