Basketball Was Forever Changed Thanks To The Lowest-Scoring NBA Game Ever

Today's NBA is a high-scoring league, one where every team, with no exception, averaged at least 103 points per game in the 2021-22 season. Granted, not everybody is a fan of the fast-paced, three-point-heavy style of play so prevalent these days, and there are those who feel that teams need to play more defense, just like they did back in the day. But as NBC Sports reported, most fans seem to appreciate the higher-octane NBA of the present.

But if one were to turn back the clock by some seven decades or so, one would see an NBA that is so far removed from the league we know and love. There was no such thing as a three-point shot, and the aerial feats performed by the likes of Michael Jordan were still inconceivable — heck, one of the NBA's first star players, "Jumping" Joe Fulks, got his nickname for his ability to hit jump shots and not his athleticism per se! Then you've got the whole matter of scoring, which there wasn't a lot of during the league's earliest years.

Back in the late '40s and early '50s, it just wasn't common to see NBA teams hit the century mark in a game, but even then, the lowest-scoring game in league history was so egregiously boring that it helped influence a major rule change that revolutionized the NBA — and basketball in general — as we know it.

The Pistons hoped to stop the Lakers' otherwise unstoppable giant by stalling

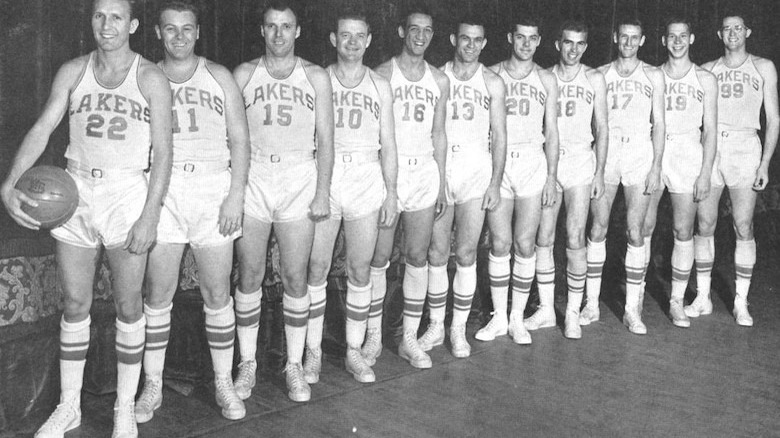

The Minneapolis Lakers — as the would-be purple-and-gold team from Los Angeles was known until 1960 — entered the 1950-51 season as defending NBA champions, and much of it was thanks to 6-foot-10-inch, 245-pound superstar George Mikan (pictured above, extreme right), the NBA's first great center and a behemoth in a league where the average player was about six inches shorter. This was a man so dominant in the middle that the New York Knicks once advertised a December 1949 home game as "Geo. Mikan vs. Knicks," as noted by The New York Times.

Just how good was Mikan on paper? According to the 1949-50 Lakers' Basketball-Reference page, the former DePaul star averaged 27.4 points on a team that scored 84.1 points per game — that's nearly a third of his entire team's average. He also shot 40.7% from the field and 77.9% from the free-throw line, with the former figure being much better than the Lakers' team shooting percentage of 36.7%.

On November 22, 1950, the Fort Wayne (later Detroit) Pistons headed to Minneapolis to play the mighty Lakers, and head coach Murray Mendenhall came up with a novel idea to counter the Lakers' high-powered (at least for that era) offense. And that was to stall, stall, stall; hold on to the ball for as long as possible in hopes of denying the Lakers a chance to dump it down low to the big guy for the easy home win — potentially their 30th straight, per ESPN.

Pistons 19, Lakers 18: The ultimate snooze-fest of 1950

The first-quarter score — Fort Wayne Pistons 8, Minneapolis Lakers 7 — was super-low indeed, but it would only get worse as the game wore on, as documented by ESPN. Halftime saw Minneapolis up by the score of 13-11, and the Lakers were still up, 17-14, at the end of the third period. Quite understandably, many of the 7,000-plus fans in attendance were not having any of this, booing the Pistons viciously for their unorthodox, yet unbearably boring strategy.

Normally, a game-winning shot from the visitors during the dying seconds of the game would be the ultimate dagger to the home team and its fans. But when the Pistons' prized 6-foot-9-inch rookie Larry Foust scored a layup over George Mikan in the last six seconds of this snooze-fest, most fans (at least the ones patient enough to stay till the end) were probably just happy that the game was over. Yes, the Pistons won, 19-18, and the Lakers' home court winning streak was snapped, but at least it was over. At last.

If the Pistons' plan was to stop Mikan from unleashing an early-'50s equivalent of beast mode in the paint, it wasn't that successful — the big dude led the Lakers with "only" 15 points. Furthermore, Lakers head coach John Kundla was furious that the Pistons sucked the air out of just about every fan in attendance, huffing after the game that "play like that will kill professional basketball."

It was only in 1954 when the NBA successfully addressed the stalling issue ... and then some

The Pistons vs. Lakers debacle from November 1950 was not the only game in the 1950-51 season where over-the-top stalling tactics seriously compromised the quality of play. On January 6, 1951, the now-defunct Indianapolis Olympians edged the Rochester Royals (now the Sacramento Kings after multiple relocations and name changes) by the score of 75-73. Sounds pretty average for the time until you realize that this game had six overtime periods, making it the longest in NBA history. A look at the boxscore is all you need to see the extent of the stalling during the overtime periods — both teams combined for just 18 points in 30 minutes of extra time, and neither club scored in the second and fourth OTs.

By the end of the 1953-54, most NBA games were still played at a glacial pace, and something had to be done to curb the trend of stalling — and the subsequent trend of games degenerating into free-throw-shooting contests in the final minutes, with teams trying to break the stall by fouling. Enter Danny Biasone, owner of the Syracuse Nationals — a team that would later become the 76ers when they moved to Philadelphia in the 1960s. By taking the number of seconds in 48 minutes (2,880) and dividing it by the combined number of field goal attempts by both teams in a typical game (120), Biasone and Nationals general manager Leo Ferris came up with what they felt was the ideal amount of time for each team to attempt a shot. Thus, the 24-second shot clock was born, and the NBA introduced it in time for the 1954-55 season.

The shot clock helped save the NBA

It would take many more years before basketball could be mentioned in the same breath as football and baseball as one of America's most popular professional sports. But the 24-second shot clock worked wonders for the NBA, a league that was in dire straits because of how frustrating it had become to watch amid all the stalling and fouling. According to The New York Times, the league's scoring average jumped from just 79.5 points per game in the 1953-54 season to 93.1 in 1954-55, the shot clock's very first season. Teams also averaged 11 more field goal attempts per game (86.4) than they did the previous campaign (75.4). And it was all thanks to Danny Biasone's idea that NBA teams should have just 24 seconds to shoot before automatically turning the ball over.

"Whatever the NBA is today is due to one little guy — Danny Biasone," said Maurice Podoloff, the league's commissioner from 1949 to 1963. "If it hadn't been for him, the NBA would not have lasted."

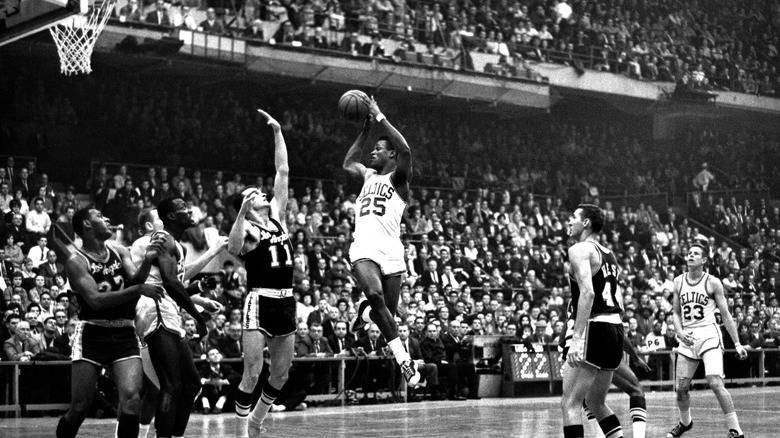

About four and a half years after the shot clock made its NBA debut, the Minneapolis Lakers lost yet another game that made the record books. On February 27, 1959, the Lakers were trounced by the Boston Celtics, 173-139, as both teams set a record for the highest-scoring NBA game. That record has long since been broken, and it was an easy win for the now-dominant Celtics, but it was proof positive of how the shot clock took pro basketball out of the dark ages and set the stage for many more scoring feats to come.