The Cultural Legacy Of The Mummified Māori Heads, Toi Moko

Visit almost any museum in the world, and there's a good chance to see some things that just aren't supposed to be there. There's a right way to do things, a wrong way, and — it turns out, there's also a really, really, really wrong way. Unfortunately, it's the latter one that gets a huge number of artifacts into museums that arguably shouldn't have them: The Archaeological Institute of America estimates (via The Verge) that between 85% and 90% of certain categories of antiquities have dubious provenance.

And that means no one's sure how they got from Point A to Point B, and when information like that isn't shared, it's probably not something that's A-OK.

The Elgin Marbles are sort of the poster child for these kinds of antiquities, although there are scores — and many are incredible, culturally important treasures to those societies they were taken from. And don't worry, because it not only can get darker, but will.

Let's talk about one group of artifacts called the Toi moko, items that have been taken from the Māori over the past few centuries. These aren't just stone or wood or clay, these are the mummified heads of Māori ancestors — and many are on display (or in storage) in museums around the world.

Imagine knowing the head of your grandfather, great-grandfather, or heck, even father, was sitting in a glass cabinet to entertain the tourists half a world away. That's actually just the start of the horrible story of the Toi moko.

What are Toi moko?

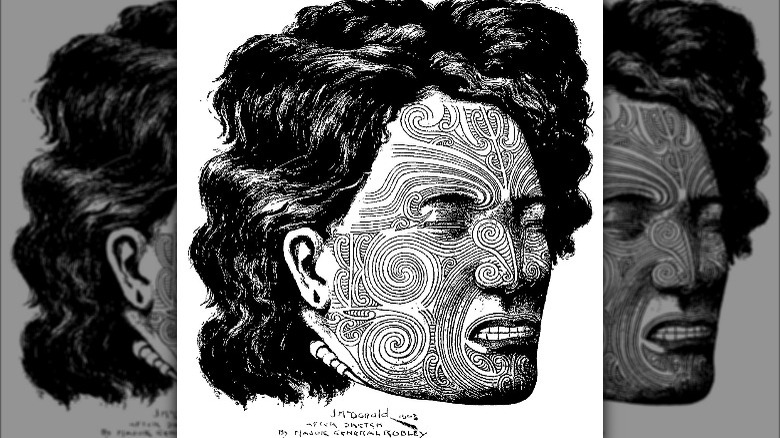

The answer to, "What are Toi moko?" is actually incredibly complicated. At a glance, they're mummified heads. According to the Smithsonian, most of the real Toi moko (and there will be more clarification on that) were usually the heads of high-ranking Māori leaders. Most of those leaders tattooed their faces with intricate designs unique to them, and when they died, their heads were removed, dried, and kept in beautifully carved boxes, which were used in sacred ceremonies.

That's really only part of the story, though, because the Toi moko are more completely about what they represent. The Staatliche Museen zu Berlin — which returned two Toi moko to the Māori in 2020 — explains that "moko" is the word for the traditional Māori tattoos. "Toi" is a little more complicated, and refers to "the origin and source of humanity, with the added dimension of reaching the highest pinnacle of artistic achievement."

In 2011, Reuters reported on the return of one Toi moko — of a total of 16 — that was being repatriated to New Zealand in a ceremony where the head was kept covered in a sign of respect. That's a far cry from being on display in a museum, and Michelle Hippolyte — co-director of New Zealand's national museum, the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa in Wellington, and Māori spiritual leader — explained, "While Toi moko have been curiosities for the public to enjoy, they are still our ancestors."

Maori facial tattoos have a long and rich history

Part of what makes the Toi moko so important are the designs tattooed into the skin: According to New Zealand Tourism, traditional Māori beliefs teach that the head is the most sacred part of the body. The placement of tattoos on the face is done to both accent facial expressions and the features of an individual — which the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa refers to as Mataora, the living face — as well as to pay tribute to a person's ancestors, heritage, and life's journey.

The tattoos — called tamoko, or tā moko — were traditionally done by using a small hammer to press pigment-dipped combs into the skin in a series of designs. Some of those designs are universal, and some have deeply personal meanings. The main lines, for example, represent the person's personal life journey and are called manawa, or heart. Other popular motifs include images like an unfurling fern representing hope and new life, but designs are unique to the individual. In 1921, Netana Whakaari of Waimana explained it pretty beautifully: "You may be robbed of all that you cherish. But your moko, you cannot be deprived, except by death. It will be your ornament and your companion until your final day" (via PBS).

It's not surprising, then, that World History Encyclopedia notes that the process of getting these tattoos was one that was steeped in generations of rituals and ceremony. Special pigments were often passed from generation to generation, and sometimes, the tattoos themselves were preserved in the Toi moko.

Toi moko were prepared for very different reasons

The Australian Broadcasting Corporation spoke with the chair of the nation of Te Rarawa, Haami Piripi, about the history of the Toi moko. The heads were removed and — before being sealed with a mixture made from shark oil — they were steamed, smoked, and dried. There were originally only two reasons to do this.

In one scenario, the deceased was a beloved ancestor who would have their life commemorated in ceremonies and rituals. According to the British Museum, Māori beliefs teach that while someone is their own person in life, they belong to the community after death — who is then tasked with caring for and honoring their mortal remains.

The second reason to make a Toi moko was to create a trophy of war. According to the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa, there were, in turn, a few different purposes for these. In some cases, they were mounted as objects of scorn and ridicule, but sometimes, they were given as gifts to celebrate victories over a rival group.

It was more than just a trophy: tā moko, Māori facial tattoos, were believed to acknowledge a person's mana, or prestige (via Staatliche Museen zu Berlin). By turning the head into a Toi moko and giving it to the victors, it was believed to increase their mana, and decrease the mana of the defeated. It was seen as a transfer of power: Sometimes — when groups were brokering peace — the Toi moko would be returned.

Toi moko were heavily traded in the 19th century

According to the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa, the first time Toi moko were traded with outsiders was when Captain Cook landed in New Zealand in 1770, and one of his crew asked the Māori for proof they practiced cannibalism. A few days later, the Māori representative returned with several Toi moko, and the crew traded for one: They took the Toi moko of a teenage boy, in exchange for a single pair of white linen underwear. Three years later, the crew of the Resolution traded a single nail for another Toi moko.

According to Trafficking Culture, it's now believed that those traded Toi moko were the heads of enemies: It had been decided to show them the ultimate insult by trading them to foreigners.

While it certainly may have had that impact, it had another one, too: It kicked off a European fascination for — and desire to own — these items that were viewed as "'savage ethnographic curios."

Supply and demand kicked off a booming market for the Toi moko, and the years between 1821 and 1830 are generally considered peak times for trading Toi moko with Europeans offering — among other things, but most importantly — guns. So many guns and so much ammunition had been pumped into New Zealand that the era's civil wars were given the name "Musket Wars," and The Guardian says Māori ancestral remains were still being imported into Europe as late as the 1970s.

For science!

Not all trade in Toi moko — and other Māori remains — was done for the sheer novelty of the idea. While a huge part was driven by well-to-do Europeans wanting something of a newly discovered, "savage" nation, some claimed they were doing it for science.

That's according to Brian Hole, a researcher at the University College London (via Public Archaeology). When Europeans started traveling to and from New Zealand regularly, they brought two devastating things with them: disease and guns. The combination of the two led to a decline in the Māori population estimated to be around 75%, and some believed that when they took remains back to Europe, they were preserving a culture for future scientific study.

One of those people was the Austrian naturalist Andreas Reischek. While his writings reveal that he had intended to sell his New Zealand collection for a massive profit, he also journaled about his lofty ambitions, calling his endeavors a "rescue operation for science."

Slavery, fake tattoos, and beheadings

By the time European demand for Toi moko got really heavy, there simply weren't enough heads to go around. The solution? Make a ton of new ones that weren't entirely authentic.

While the Toi moko originally started out as a sacred practice preserving the memory and life of spiritual and tribal leaders, enterprising traders started getting less and less fussy about the heads they were taking. Many of the Toi moko that made it into the hands of European collectors were the heads of slaves and prisoners of war. According to the Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, these people would be given facial tattoos before they were executed, for the sole purpose of turning their head into a Toi moko.

Trafficking Culture says some of the heads can be identified by "iconographic errors" in the tattooing: While true Māori tattoos have deep meanings and are designed in specific ways, the Toi moko made from slaves and prisoners just had to be good enough to fool Europeans. It didn't really matter, they just had to look the part — particularly because while some ended up in collections and museums, others just sort of ended up in private homes.

Haami Piripi, chair of the nation of Te Rarawa, explained to the ABC: "They'd put them on their mantelpieces, stick a candle on top of it or something. It was really, really bizarre."

The conflicted legacy of the Robley collection

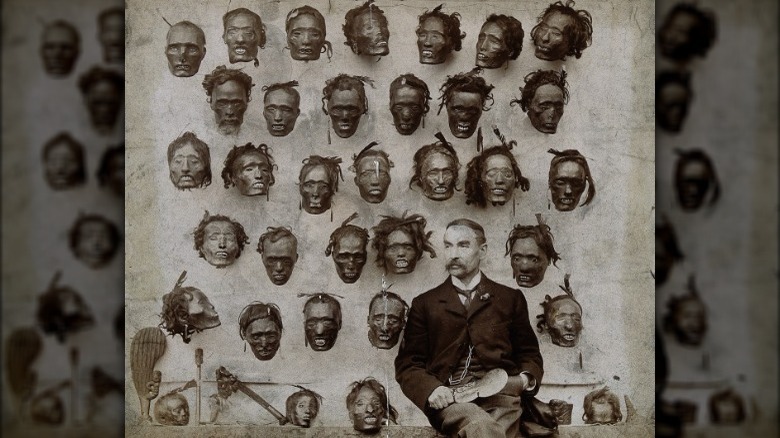

There aren't going to be too many Māori-approved photos of Toi moko in existence: According to the Sunday Star-Times, the list of people who are actually allowed to view the heads is a short one — and it doesn't include anyone from the media. That said, one of the most notorious photos is that of Horatio Gordon Robley.

Robley — who served in New Zealand during the Māori Land Wars — went back to London and was horrified at the heads that were making the rounds. According to the American Museum of Natural History, Robley spent a shocking amount of money buying all the heads he could (including the one illustrated here) in a project that started when he first purchased one from a London phrenologist. He accumulated somewhere around 50 Toi moko — and then, he offered to sell them back to New Zealand for a fraction of what he paid. New Zealand refused, and the collection ended up going to the American Museum of Natural History.

Robley wrote a book called "Moko; or Māori Tattooing," in which he condemned the fact the Toi moko were ever allowed to leave their home in the first place. He called the whole thing "gruesome," and "sordid," and his determination to buy as many as he could bankrupted him.

Robley died penniless, buried in a London pauper's grave. Although he didn't live to see his collection return home, it did: In 2014, Te Ao announced the repatriation of Robley's collection.

The organization behind the repatriation requests

Today, an organization called Karanga Aotearoa is working to try to do what Horatio Gordon Robley was doing at the turn of the 20th century: get Māori remains back to their ancestral lands. In 2003, the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa (pictured) was officially put in charge of locating remains — including not just Toi moko, but skeletal remains as well — and negotiating for their return.

How's it going? Well ... it's going.

The Māori have been asking for the physical remains of their ancestors back for a long time. In 2021, The Guardian reported that the Canterbury Museum finally agreed to return the ancestors of the Rangitane o Wairau iwi (or tribe) back to them, after 60 years of asking. Other museums have also started to step up: In 2020, Germany's Ethnologisches Museum of the Staatliche Museen zu Berlin returned their Toi moko, and in 2017, Oxford's Pitt Rivers Museum returned its seven Toi moko.

The remains initially go to a sacred space called a wahi tapu, where they rest as Karanga Aotearoa carries out the second part of the repatriation: And in many cases, it's incredibly complicated.

The problem of provenance

In 2007, representatives from the British Museum went to New Zealand to discuss repatriation requests and found that it wasn't straightforward.

A huge part of the problem is provenance. Perhaps unsurprisingly, there's not a whole heck of a lot of reliable documentation to tell just who the heads were, where they came from, and which one of the 81 iwi — or tribes — the remains belong to.

It's made even more difficult by the fact that some are legitimate Toi moko, some were made by tattooing and executing slaves and prisoners, and it's kind of impossible to tell which is which. (In his book "Moko; or Māori Tattooing," Horatio Gordon Robley even cites instances where chieftains would introduce potential buyers to his slaves, ask which head they would prefer, and promise to deliver as soon as it was tattooed, removed, and prepared.)

Attempts have been made to try to figure out a way to tell just where a Toi moko is from, but it's been slow going. Individual tattooists, regions, and iwi may have had their own styles, but they weren't always observed. Hairstyles might give a clue, but they're not always preserved. Stitching patterns are too common to be associated with an iwi, and DNA analysis has also been a failure because of the large amount of intermarrying between iwi.

That all means the risk of interring an enemy alongside beloved ancestors is very real, and not many are willing to take the chance of disrespecting their own.

When a Toi moko becomes just another thing

There's also the question of whether or not an iwi wants remains back, and a large part of the answer to that question is rooted in Māori beliefs.

Per a 2007 paper published in the journal Public Archaeology and titled "Playthings for the Foe: The Repatriation of Human Remains in New Zealand," Toi moko got their significance from the belief that they contain both mana — defined as spiritual authority, charisma, and prestige — and tapu — the state of being sacred. He cited a story that showed just how strong the belief was, and it involved two brothers, both running for their lives from an enemy. One was wounded, and asked the other, "Do not leave my head a plaything for the foe." In a heartbeat, his brother chopped off his head, escaped with it, and turned it into a Toi moko.

According to the British Museum, Māori teachings also say that depending on what happens to a person during his or her lifetime will cause their humanity to grow stronger or to weaken — and it's further taught that the things that happen to a person's remains cause the same thing. When they interviewed Māori amid repatriation requests, some said that some events — enslavement, tattooing with meaningless symbols, and the selling of his head — would diminish the mana so much that the head would simply become a thing, and having it returned was no longer needed. Not all Māori feel that way, but it shows that it's not a straightforward issue at all.

Museums in New Zealand also have remains

It makes sense to point the finger at museums and collectors in Europe and demand that the Toi moko and other ancestral remains be returned, but that's not the whole story. Dr. Amber Aranui, a curator at the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa, started surveying the country's own museums in 2018. When she did, she found something shocking: They were in possession of at least 3,300 sets of remains, with the overwhelming majority being either Māori or Moriori.

That prompted her to start working on a series of guidelines for "domestic repatriation," which is an attempt to identify and return remains still in New Zealand, but not in the possession of the Māori iwi. The Guardian says her work has formed the basis of other repatriation guidelines, and again, not the end of the story.

When University College London researcher Brian Hole looked at how ancestral remains and Toi moko made their way abroad, he found that while many were obtained via trading with Māori selling the heads of their enemies and more than a few had been sourced by graverobbers, there was another unlikely source: New Zealand's museums (via Public Archaeology). He says that at the end of the 19th century, they began filling their own collections with items from all over the world, which they got by offering up Māori Toi moko and ancestral remains. It's prompted the nation to take a long, hard look at their own practices.