The Controversy Over The Elgin Marbles Explained

There are few historical sites more renowned than the Parthenon in Athens, Greece. As described by Britannica, this temple — dedicated to the goddess Athena Parthenos — was built between 447 and 438 B.C. upon the Acropolis during a massive renovation project of the city by the statesman Pericles. The Parthenon is a significant piece of Greek architecture that signaled the Greeks' victory in the Persian Wars, and its harmony and aesthetic sense have strongly influenced architecture up to today.

Equally significant was the temple's beautiful sculpture. The Parthenon featured chiseled scenes detailing figures and scenes from ancient Greek mythology. Each one of the metopes, the chiseled spaces above the columns, featured ancient mythical battles. The pediments, which are the upper triangular gables, contained complex scenes out of Greek religion. Perhaps the most renowned sculpture was a great golden statue of the goddess Athena inside the temple made by the famous sculptor Phidias.

If you were to climb the Acropolis and visit the Parthenon today, you would see none of those sculptures. Only half managed to survive through the ages, and none remained on the Parthenon. One half is in the Acropolis Museum in Athens, and the other half in The British Museum in London. How these sculptures came to London is at the heart of the great controversy of the Elgin Marbles.

The significance of the Elgin Marbles is hard to understate

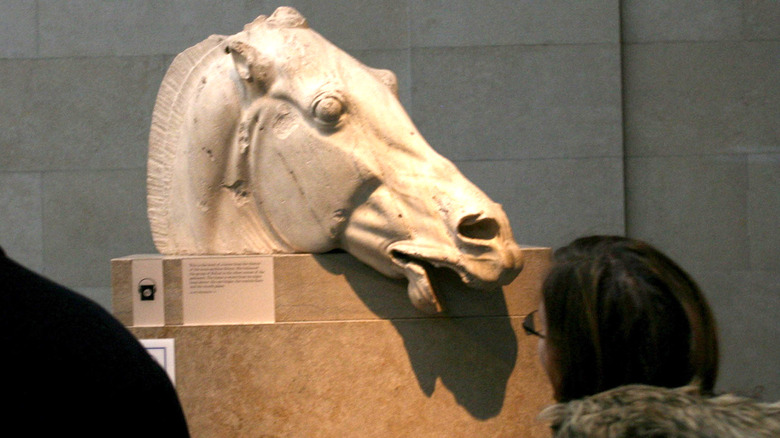

The Elgin Marbles are those sculptures from the Parthenon that are housed at the British Museum, where they are properly called the Parthenon Sculptures (via Britannica). The scope of the holdings at the British Museum consists of 15 metopes — which depict a battle between centaurs and a mythical tribe of humans called the Lapiths — 17 pediment figures of gods and mythical figures, and 247 feet of the original frieze depicting a procession of the Panathenaic festival that celebrated the birthday of Athena.

Live Science provides some detail on the most well-known of these sculptures, such as pedimental sculptures that show reactions to the birth of Athena, who erupted from Zeus' head fully armored. Each one of these sculptures is highly lifelike and idealized, representing the pinnacle of Greek art. Curiously, in classical Greece, visitors to the Parthenon would have likely experienced the sculpture not in marble white but in vivid color along with the rest of the building. Perhaps this would have made the viewing of the sculpture in its original form more moving. The Guardian called them "miracles of sculpture," and they are defining art for Greek identity and nationhood.

The Parthenon and its sculptures were in danger

The Parthenon as a structure has a long and complicated history. The World History Encyclopedia explains how in late antiquity, it was converted into a Christian church. To do this, a portion of the east frieze was removed to make room for an apse. Further modifications saw the removal of some of the metopes as well as the addition of a bell tower. In 1458, the Ottoman Empire converted the Parthenon into a mosque, complete with a minaret.

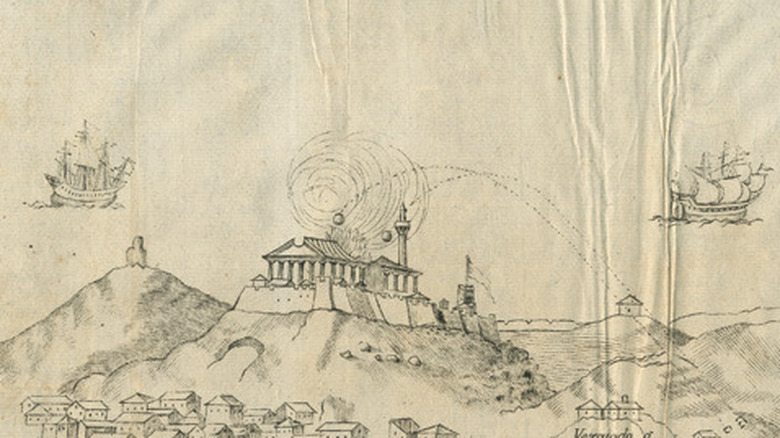

While some damage had been done to the building, it generally survived with a good deal of its sculpture. However, disaster struck in 1687 when a Venetian army laid siege to the Acropolis of Athens. Unfortunately, the Ottomans were using the ancient site as a powder magazine, and a Venetian shell destroyed the Parthenon. In the explosion, all the interior walls were destroyed, and much of the exterior crumbled. More galling still was that Venetian Admiral Francesco Morosini attempted to take some of the sculptures in the looting but only managed to destroy more sculptures in a pulley accident, including a large figure of the god Poseidon (via National Geographic).

From that point, the Parthenon lay in ruins, and little was done to protect its antiquities. In fact, it was common for a casual traveler to take home a piece of the Parthenon as a souvenir.

The 7th Earl of Elgin wanted Greek art to decorate his Scottish estate

It was in the context of the ruined Parthenon that Thomas Bruce, the 7th Earl of Elgin, entered the scene. Born in 1766, Britannica explains that Bruce became Earl of Elgin in 1771 and, after a stint in the British army, became a diplomat in 1790. In 1799, he was named envoy extraordinary to the Ottoman court in Constantinople. According to Smithsonian, Elgin's goal was to woo the Turks into an alliance against Napoleonic France.

Lord Elgin had a personal passion for ancient art and architecture, and he took it upon himself to lead a mission to draw, create molds, and record ancient artifacts in Ottoman-controlled Greece. To this end, he assembled a team of artists (financed by the fortune of his wife) while en route to Constantinople. These were headed by the Neapolitan artist Giovanni-Battista Lusieri. The project helped extend knowledge of ancient Hellenic civilization to other parts of Europe. But Elgin also had a strong interest in acquiring at least some of these artifacts to feather his nest. He was building a new home in his native Scotland, and The Journal of Hellenic Studies studies quotes Elgin writing to Lusieri of his new quarters, "This building is a subject that occupies me greatly, and offers me the means of placing offers me the means of placing, in a useful, distinguished and agreeable way, the various things that you may perhaps be able to procure for me."

Lord Elgin received permission

In Constantinople, Lord Elgin began his diplomatic work while he sent Giovanni-Battista Lusieri to Athens (via National Geographic). At Athens, Lusieri had permission to freely sketch the city's famous sites with the exception of the Acropolis. The reason for this restriction is laid out in "Lord Elgin's Firman." The Acropolis was a fortress, and there were military sensitivities. In addition, the Parthenon was a mosque. Plus, there was a sense on the part of the Ottomans that they could profit by granting admission to the Acropolis. Typical entry fees amounted to coffee, sugar, or textiles. However, Lusieri was quoted a usurious five guineas a day. National Geographic describes how Lusieri urged Elgin to receive special permission from the Ottoman court in what was called a "firman." Firmans covered a wide range of documents, including travel permits, imperial directions, and appointments.

On July 6, 1801, Elgin received what was apparently just the thing. The letter expressly gave permission to Elgin's team to draw, cast molds, and set up scaffolding to do the work unmolested. Furthermore, the letter also read, "should they wish to take away any pieces of stone with old inscriptions, and figures, that no opposition be made." Elgin interpreted this to mean that he could haul away anything that he wanted.

Was Lord Elgin's firman legitimate?

If the original intent of the firman was to give permission to remove just loose stone laying about or to actually excavate and remove substantial portions of the Parthenon is unknown. "Lord Elgin's Firman" notes that the original firman is lost, and what is left is an Italian translation which was kept by Philip Hunt, Lord Elgin's chaplain. There is even some questioning as to whether the letter was a legitimate firman.

The document was signed by Kaimakam Seged Abdulah, a government official who used his seal rather than that of the sultan. One scholar has argued that the document is not a proper firman since it is not from the sultan but and thus a mektub — just a letter. In any case, the British called the document a firman, and that is how they have historically treated it. Regardless, the Ottomans at the Acropolis did not oppose Elgin's men when they went to dismantle the Parthenon's sculptures.

The Elgin Marbles were packed up in about 200 boxes

With permission granted — or assumed granted — Lord Elgin dismantled wholesale portions of the Acropolis. According to National Geographic, Giovanni-Battista Lusieri and his team dismantled large portions of the Parthenon, taking part of the frieze, numerous metopes, and other statuary. By 1803, these were all stowed into about 200 boxes and sent by wagon to Piraeus, the port of Athens. This was all done at Elgin's expense. The British Museum points out that by this time, about half of the original sculptures had already been lost. Elgin would eventually take half of that, representing about a quarter of the original sculptures that adorned the Parthenon.

The shipping of the Parthenon sculptures was not without trouble. One of the ships wrecked near the isle of Kýthira, and it took two years to recover the lost sculptures. Meanwhile, the heaviest sculptures were taken by a British warship to keep it out of French hands. This was accomplished, although Elgin himself was captured on his homeward journey. He was held in prison for three years until 1806. After his release, he negotiated a second shipment of sculptures, which sailed in 1809.

Controversy started at once

Even in Lord Elgin's own day, the removal of the Parthenon's sculptures was controversial. "Greek Studies in England 1700-1830" makes a record of some contemporary criticism, with one commenter stating, "the Athenians in general, nay even the Turks themselves, lament the ruin that was committed." An architect of the time reportedly stated, "All who visit Athens will abhor Lord Elgin." Not long after the departure of the Elgin Marbles, one traveler found the graffiti "Quod non fecerunt Goti, Hoc fecerunt Scoti" etched onto another Athenian ruin, which translated means that "what the Goths did not do, the Scots did." Sharp criticism was also leveled by Lord Byron. For example, in the poem "Childe Harold's Pilgrimage," Bryon alluded to Elgin as a Pict, which was a people of ancient Scotland.

He wrote: "But most the modern Pict's ignoble boast / To rive what Goth, and Turk, and Time hath spared / Cold as the crags upon his native coast / His mind as barren and his heart as hard / Is he whose head conceived, whose hand prepared /Aught to displace Athena's poor remains / Her sons too weak the sacred shrine to guard / Yet felt some portion of their mother's pains / And never knew, till then, the weight of Despot's chains."

To the Greeks, Elgin was an imperial pillager

The Greeks were obviously the group that was the most appalled at the removal of the Parthenon's sculptures. Their position is easy to appreciate. Athens had been occupied by the Ottoman Empire since 1458. To the Greeks, the Ottomans were an occupying power that had no connections to the great works of classical Greece (via Smithsonian). In their view, they did not have the moral authority to distribute that heritage to another imperial power that had no connection to Hellenic heritage either.

The Parthenon was perhaps the most famous of classical Greek works and demonstrated the power and richness of Greek culture at its apogee. Thus, when the Greeks began to fight successfully for independence in 1821, the Elgin Marbles became a unifying symbol of Greek nationalism. When the independent country was established in 1832, the Greek government petitioned the British government for the return of the Parthenon sculptures (per National Geographic). Yet by that point, Britain had dug in its heels.

Elgin sold the marbles to the British Government

When the Parthenon sculptures came to Britain, they were first kept in Lord Elgin's private collection. According to National Geographic, Elgin originally wanted to restore the sculptures by recreating the missing pieces. However, when Venetian sculptor Antonio Canova was approached with the prospect, he refused, asserting it would be "sacrilege" to touch them. Instead, Elgin put them on public display at a house he rented in London. This proved to be very popular.

However, things were not going well for Lord Elgin. He had spent £74,000 on the sculptures, and in 1808, he reached a divorce settlement with his wife that further hurt his purse. Meanwhile, he responded to criticism by publishing a defense of his acquisition. This was also probably used to promote his marbles since his next move was to push the British government to purchase the sculptures. In 1816, Parliament created a commission to investigate the issue. They eventually declared Elgin's acquisition legal and bought them for £35,000. To illustrate how divisive the purchase was, Parliament only approved the purchase by two votes. It is notable to mention that while Elgin took a loss, he also refused to sell to other foreign governments, which offered him more. To Elgin and those who supported the purchase, the acquisition of such a historic sculpture was a symbol of British power and influence.

The Greek government has repeatedly asked for the Parthenon sculpture back

After the British government acquired the Elgin Marbles, it was stored in a temporary facility. Then, in 1832, it was moved to the British Museum (via National Geographic). That year happened to be the same year Greece was formally recognized by treaty as an independent nation. Greece periodically sent petitions to the British government for the return of the sculptures. The Greek government even established the Acropolis Museum in 2009, which includes the Parthenon Gallery. This gallery contains what remaining sculpture was left at the Parthenon, as well as plaster copies of the Elgin Marbles and scattered sculptures in other museums. The World History Encyclopedia tells us that these sculptures are arranged in the way that they would have been originally on the Parthenon.

As for the Greek request to return the Elgin Marbles, the British Museum has consistently refused to do so. Perhaps it is because it is one of the museum's more popular attractions, but it has other reasons that make this controversy debatable. For example, as HistoryExtra asks, does this mean that all artifacts from museums around the world should be repatriated to their country of origin? If so, then most of the major museums around the world would be impacted and possibly face damage to their educational missions.

The British Museum entertains the idea of a loan

The ultimate fate of the Elgin Marbles lays with The British Museum. Their official position, however, seems inflexible. They assert that the acquisition of the sculptures was completely legal since they hold the firman to be a legal document from the authorities at the time, plus it was upheld as legal by Parliament in 1816. Furthermore, they contend that while the Greek government made an official request for the return of the sculpture, it never has acknowledged the right of ownership to the Trustees of the British Museum.

The British Museum has also argued that the Elgin Marbles are well-suited in the broader context of the global collections at the museum and notes that many ancient artifacts are divided between different institutions. What they do entertain is the idea of loaning the sculptures to Greece. This would fly in the face of Greek sentiments that the sculptures belong culturally, historically, and morally to them. In fact, The New York Times reported in 2009 that the Greek government rejected an offer of a loan. The Greek culture minister at that time stated that accepting a loan would pardon "the snatching of the marbles and the monument's carving-up 207 years ago."

Technology may provide a solution

The controversy of the Elgin Marbles seems to be in a perpetual deadlock. However, there is hope that a resolution may be reached. In 2022, The Art Newspaper reported on an interview with the chairman of the British Museum, George Osborne. Osborne stated there is a "deal is to be done where we can tell both stories in Athens and in London if we both approach this without a load of preconditions, without a load of red lines." Meanwhile, public protests and pressure continue to mount on the museum to return the artifacts, led by such groups as the British Committee for the Reunification of the Parthenon Marbles. This group took particular umbrage at Osborne's comments, with one member of the committee, Professor Andrew Wallace-Hadrill retorting (via The Art Newspaper), "What other stories do they tell in London? Of the willingness of an imperial power to help itself to the monuments of another civilization?"

Despite the criticism at Osborne, he is the first chairman of the museum to acknowledge that the sculptures returning in some form to Athens may be beneficial. One possible solution is using 3-D technology to create exact replicas of the sculptures (per The Guardian). In fact, it is already being used by the museum to create faithful copies of some other sculptures. Whether this will allow the museum to save some face and end the boiling debate remains to be seen. But doubtless, if the status quo remains, the controversy shall continue unabated.