The Untold Truth Of Thomas Jefferson

There have been some pretty great Americans in the rather short timeline of the United States of America, and while they absolutely don't always end up being presidents, some of the best have. The first two that likely come to mind are George Washington and Abraham Lincoln, but another Founding Father should rank in the not too distant third — Thomas Jefferson. Like all mortals, he had his share of controversy and flaws, but when looked at through the proper lens, his legacy contains lots of positivity. The University of Washington ranks him as the seventh greatest American of all time, and when you consider the company, that's saying something.

But given the legacy that he left alongside the Founding Fathers and the Constitution, as well as his own individual quirks and personal quests, there are always going to be some little tidbits that get lost in the shadow of his governmental work. He was more than just a president, and he did more than just help create the United States, though those achievements alone are pretty outstanding. Here are some of the untold truths of Thomas Jefferson's life and legacy.

He single-handedly saved the Library of Congress

Thomas Jefferson had a great many passions, many of which will be covered here, but no passion ranked higher than his love of books. In fact, it's a quote from Jefferson that is so often used by book lovers out there (via the Library of Congress) — "I cannot live without books." Jefferson was on an eternal quest for knowledge of all sorts, so books were his ticket to that goal. After all, how else can a man become so diverse in knowledge as Jefferson? But his history with large collections of books is almost as storied as his history as a Founding Father.

In 1770, his family home burned down and took his library with it, according to the Library of Congress. He was only a teenager at the time, but the loss was devastating. Still, he began collecting again, and by the 1780s, when he was ambassador to France, he had built a significant library at Monticello, with his volumes numbering in the thousands. No doubt he read nearly every single one of them. Then, in 1814, when the British took the United States capital and burned down the Library of Congress, Jefferson stepped in to save the day. He offered his personal collection to Congress for whatever fee they deemed fit and sold 6,487 of his books to the government. While two-thirds of those were lost in a fire in 1851, Jefferson's collection still remains the heart of the largest collection of books in the world.

He was an influential foodie

While Thomas Jefferson had a lifelong hunger for knowledge, he also had a hunger for good and unique food. Jefferson first forayed into the world of culinary satisfaction while he was the United State's ambassador to France. He studied the art of cookery while there and fed a whole new passion that left a lasting impression on the fledgling United States (via Monticello). While foods like ice cream were yet to really find any traction, Jefferson's love of it helped it become what is now a pretty hefty scoop of American food culture.

Jefferson also secured the importation of olive oil and French mustard, two more pieces of the American culinary scene that can be found on practically every grocery store shelf in the nation, and it all began with one man's love of food. Oddly enough, while not a full-on vegetarian, Jefferson viewed vegetables as the most important food and ate meat "as a condiment to the vegetables which constitute my principal diet," according to Monticello. Which, needless to say, was a bit of an oddity for the time.

On returning stateside at the end of his tenure in France, Jefferson brought new recipes galore, some of which still survive today, including recipes for almond cream, pasta dough, and french fries. Although, for Jefferson, they were known as "potatoes deep-fried while raw, in small cuttings," according to National Geographic.

He battled with pirates

Somehow, this little episode of American military history often gets forgotten. Thomas Jefferson was inaugurated in 1801, and while his young nation had just fought off the British for independence, they were by no means out of the dense forest of conflict. Given the fledgling state of the nation, it was a prime target for the Barbary pirates during the First Barbary War, according to Monticello. Going back as far as 1784, the United States had been attempting to find peaceful terms with the Barbary States of North Africa and the Mediterranean.

At the time, European powers simply paid off the Barbary corsairs (not technically pirates) and left it at that. While Jefferson opposed it, America initially decided to pay off the pirates as well, but by the time his presidency rolled around, tensions were brewing with changes of leadership in North Africa. Jefferson sent ships to protect American trade interests overseas from the corsairs while pushing for peace. But rather than pay for peace, Jefferson continued to push for funding to win the war instead, and by 1805, an improved navy and crack sailors were able to subdue the corsair menace in the Mediterranean and give Jefferson a very hardy victory.

He dressed for comfort, not for presentation

When you think of the Founding Fathers, or any stately gentleman or lady of the 18th and early 19th century, you probably think of very specific fashion — long-tailed coats, hats, leather shoes, powdered wigs, corsets, and the like. We've all seen the paintings, and that's apparently what everyone wore at all times. Not Thomas Jefferson, though. Jefferson was a man of comfort, not of what he saw as unnecessary frills.

While Jefferson had a stately home at Monticello, with fine arts hanging from the walls and food that mixed foreign innovation with American invention, his own presentation was often regarded in a somewhat different light. Where his walls bore all the fanciness the world had to offer, Jefferson bore worn-out slippers and ragged robes, according to "Jefferson on Display: Attire, Etiquette, and the Art of Presentation" by G.S. Wilson. And while that could be brushed off as being in the comfort of his own home, the same can not be said of British minister Anthony Merry remarking that Jefferson's appearance to be "in a state of negligence."

It made for quite the intriguing combo — to have such fine foods and art, as well as the intelligence of Jefferson, mixed with what can only be described as a haphazard appearance.

He was up to his eyes in debt

Most people probably wouldn't imagine a president to be burdened by such a ferocious a debt as Thomas Jefferson, especially considering all of his expensive habits and travels and how he seemed to live quite comfortably. Yet, despite ranking as the president with the second highest net worth of all time, Jefferson carried with him in life a debt that, adjusting for modern day inflation, would have totaled over $1 million, according to Monticello.

It began before the Revolution with his attempts at tobacco farming, then ballooned when he assumed the debt of his father-in-law. All attempts at paying the debt off were met with familiar modern frustrations — interest and inflation. No matter what he paid, the debt never seemed to get any smaller. According to his estate, however, a lot of the problem also stems from Jefferson's ignorance of how much profit he was actually sitting on. Jefferson was well aware of his debt, however, and once remarked (via National Archives) that "I am miserable till I owe not a shilling."

And yet, despite the heavy weight of debt and the auction that occurred after his death, Jefferson, by the account of his own daughter, still managed to die peaceful and happy. Credit it to his optimism. If only optimism had monetary value, Jefferson likely would have died free of debt too.

He had glossophobia

Another preconceived notion that many have about the Founding Fathers as a collective group is that they are noble, outspoken statesmen who could debate their way out of practically anything. With more inspirational quotes than online databases know what to do with, surely these men were just spitting wisdom from podiums at all hours of the day? But for Thomas Jefferson, that wasn't necessarily the case. Jefferson has a copious amount of famous and inspirational quotes (via Monticello), such as "Never put off till to-morrow what you can do to-day" and "Never spend your money before you have it," but the interesting twist is that very few — if any — of these quotes were actually said out loud. They were written.

That's because Jefferson was not a very confident public speaker and was often noted for his mumblings and lack of eloquence with the spoken word. Perhaps the most telling testament to this is Jefferson himself writing (via Founders Online): "My great wish is to go on in a strict but silent performance of my duty." Still, as president, Jefferson had to speak, if only just at both of his inaugural addresses. While both were notably packed with wisdom and wit, they were also, rather comically, barely audible, according to Monticello. Throughout his time in public office, Jefferson continued to rely on the written word rather than be forced into spoken word.

He was also a founding father of the University of Virginia

In case this hasn't been made clear already, Thomas Jefferson had a lot of passion for a lot of different things — books, knowledge, food, and more. Ranking in his most prominent passion of public policy, however, is his quest to make education more accessible to literally everyone while also making it more beneficial in general. One of the greatest contributions he made in that regard was in the founding of the University of Virginia. It first came to Jefferson when he was serving as the vice president of John Adams. He wanted to build, in the center of Virginia, a university "so broad and liberal and modern," according to a letter he wrote (via National Archives).

After his time as president, Jefferson continued on the board of what was then known as Albemarle Academy, seeking to establish a university exactly like the one he had written about. When construction finally began, Jefferson was named rector of the university (per Monticello). The university officially opened in 1825, with a complete staff of foreign professors — soon augmented by a few Americans — and Jefferson lived just long enough to visit the school once before his passing on July 4, 1826. He is remembered as "The Father of the University of Virginia."

He was one of America's first wine-o's

Nowadays, being a wine aficionado makes you one of a multitude. There is an entire genre of wine writing by people who can differentiate the different tastes and makes and vintages and all kinds of intricate concepts all tied to the beverage coined by Dionysus. But long before it had such a popular appeal, Thomas Jefferson counted himself as one of the first to be truly passionate about wine. Of course, having spent as much time in France as he did and being such a culinary gourmand, the matching may seem inevitable. Regardless, Jefferson himself wrote (via National Archives) that "in nothing have the habits of the palate more decisive influence than in our relish of wines."

And while his love of wine was mostly driven by palate, he did make a political decision to forsake all British wines following the Revolution and instead favored French and Italian wines, neither of which left such an oppressive taste in his mouth. Throughout his innumerable correspondences via letter, Jefferson frequently wrote of his taste for wine, highlighting one factor or another, all of which, even when read today, sound like they were written by a modern wine reviewer. Per Monticello, such notes include: "as sweet as the silky Madeira, as astringent on the palate as Bordeaux, and as brisk as Champagne" and "fine aroma, and chrystalline transparence."

He advocated for the poor

There is a certain "pick yourself up by the bootstraps" mentality often attached to the Founding Fathers. These were, after all, a collection of men who, on wanting a better nation, created that nation. But that doesn't mean that they were all without charity or compassion for those less fortunate than them, and no one displayed this quality better than Thomas Jefferson in his quest to help the poor. Along with his desire for more accessible education for all, Jefferson also proposed revolutionary and refreshingly liberal ideas for the treatment of the poor. Such ideas included that the government of the community should care for the poor, not just private charity, according to The Heritage Foundation. He also wanted a personalized approach to helping those in need, ensuring that everyone got what they needed, as opposed to a blanket solution that might not be what the impoverished needed in the first place.

Jefferson spent his political life trying to secure the liberties of the working class and of ordinary people, and while not all of his efforts came to fruition, it wasn't for want of effort. As noted by The Heritage Foundation, Jefferson had many ideas to provide for those in need.

He was more or less an archaeologist

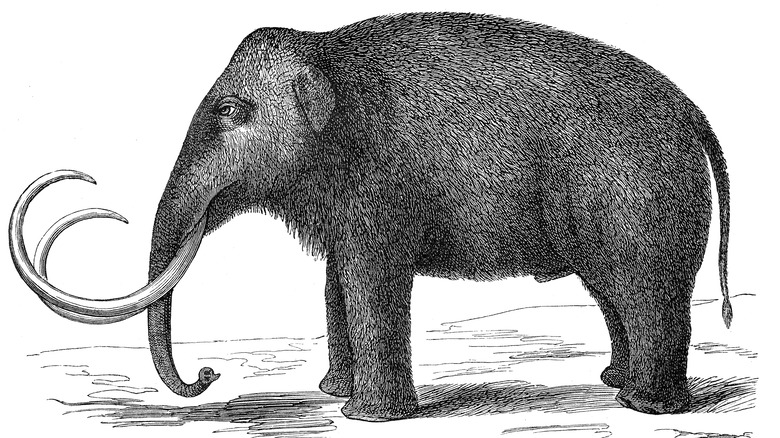

The list of things Thomas Jefferson could be considered at least mildly proficient at seems to grow every time you look at his illustrious educational background. Counted among his list of skills and passions is archeology, the study of bones and remains. In fact, his excavation of what is now known as Jefferson's Mound Archaeological Site is the site of the very first scientific instance of archaeology in the history of the United States. While the impetus behind the excavation and the subsequent act of unearthing it is a little dubious — considering it is a Native American burial ground — Jefferson's passion for the study of the past didn't end there.

Jefferson also commissioned the likes of William Clark and Meriweather Lewis to do a bit of digging themselves, and one such dig turned up a mastodon jaw, perhaps the most famous fossil in Jefferson's personal collection. He also had fossils of giant ground sloths and woolly mammoths, according to the Academy of Natural Sciences at Drexel University. And speaking of said University, its founding in 1812 was another major step on the American scientific front, and it now houses the complete collection of fossils from Thomas Jefferson's scientific studies.

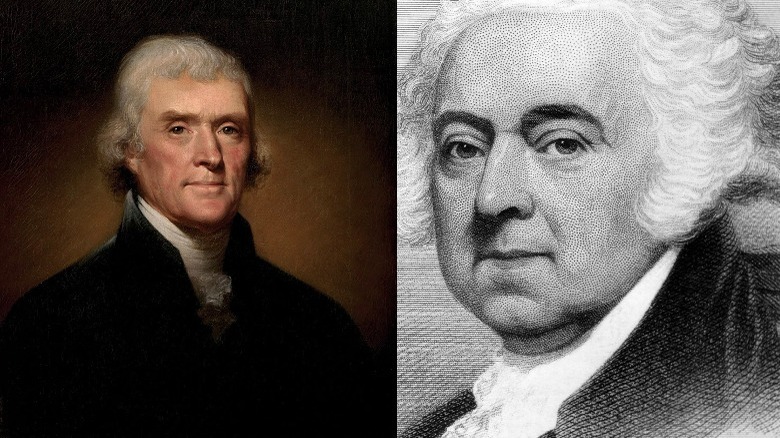

Him and John Adams were frenemies

Pick any two Founding Fathers, and you can find a very particular and storied relationship, but no two had a more complicated relationship than Thomas Jefferson and the man he served as vice president for: John Adams.

Their storied relationship began at the separation of political ideals, with Adams veering toward a large centralized government and Jefferson leaning more toward states' rights and letting the locals govern themselves. However, given the need for unity in the fledgling United States, they gravitated toward each other, according to CNN. That is until a series of presidential nomination and elections put a bit of a nasty feeling between the two of them. When Adams eked past Jefferson in the election for the second president of the United States, Jefferson had to serve as vice president because that's just how things worked. Naturally, Jefferson was less than a fan, and things got heated. Then, in 1800, when Jefferson won over Adams, Adams was less than a fan.

They went from friends to political adversaries to not talking for 12 whole years. It was still a small country, and to not talk to someone for 12 years required effort — and they were too willing to give that effort. Curiously, they both died on the 50th anniversary of America's freedom, July 4, 1826, within hours of each other.

He was an architect

If you're keeping track of the number of things Thomas Jefferson was, you might have lost count by now, but he was also a renowned architect who began on said path when he was still a student at the College of William and Mary, according to Encyclopedia Virginia. The architectural resume of Jefferson is as illustrious as his presidential resume, believe it or not, with his most notable projects including the state Capitol building in Richmond, Monticello itself, and significant portions of the University of Virginia. He also had a lot of influence on the design of the White House and the United States Capitol building. More than that, his influence can be seen all over in the classical inspiration of the capital.

From very early on in his architectural journey, he was influenced by Andrea Palladio, who, among other things, insisted on the use of columns — a feature that Jefferson used to masterful effect in practically every building project he was attached to. So every time you see a column in D.C., you can probably guess who put it there.