The Controversial Life Of Cecil Rhodes

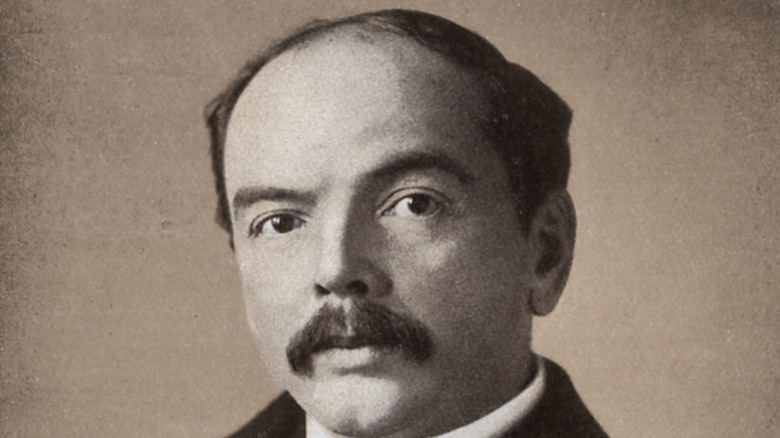

To say that Cecil Rhodes is controversial is rather like saying that Hitler had a global outlook. Despite his defenders, Rhodes is largely synonymous with the worst excesses of colonialism and a support for the British Empire that was so fervent it even made several of his contemporaries wonder if he might be a tad racist.

One thing the anti-woke brigade does get right is that the late 19th century was a very different time. Rhodes was no monarch or military man, and yet he was able to turn up in an area of the world many Europeans viewed in the same way Americans saw the "Wild West," not just to make his fortune, but to take over as prime minister, all within a few short years. Until very recently, the place we now call Zimbabwe was named "Rhodesia" after the man himself. And in case anyone forgot, he financed a few statues of himself to prove it. Given his humble origins, it's hard not to marvel at the scope of his ambition.

The "Rhodes Must Fall" campaign, which has pushed hard for these statues to be brought down, has gained major momentum in the last decade, supported by movements such as #BlackLivesMatter. Efforts to topple his likeness have led to a renewed focus on his legacy, becoming a crucial pivot point in the so-called "culture wars." Yet his far-from-ordinary story is complex. Below is an attempt to extract the man from the dark myth.

A colonial childhood

Cecil Rhodes was born in 1853 into a clergy household in Bishop's Stortford, a town in the English county of Hertfordshire, according to the BBC. He was educated at the local grammar school, but his poor health and humble family background meant he was unable to attend Oxford or Cambridge. It's fair to say this might have given him an inferiority complex. Most people learn to internalize their disappointment about not getting into their favorite college — yet Rhodes responded with his own attempt at world domination. While it's tempting to ignore any teenage boy who tells you he'll be rich before he's 30, the unfortunate inhabitants of southern Africa were soon to discover how serious he was about this.

Rhodes suffered from tuberculosis, and his family felt that sending him to Africa, where the climate was warmer, at the age of 17 might improve his condition. His brother Herbert was already out there, and in keeping with a common tradition in colonial-era Britain, his family chose to outsource their more problematic offspring, despite the protestations of the rest of the planet.

Unusually for the time, Rhodes paid out of his own pocket to attend Oxford University, for one term in 1873 (as highlighted by Oriel College, his alma mater), returning to continue his studies in 1876 (according to Oxford History) and eventually completing his degree in 1881. With his ambition to study at Oxford finally fulfilled (albeit in a half-assed way), you would think he might slow down from here. You would be wrong.

Diamonds are forever

On arriving in South Africa, Cecil Rhodes started out in cotton production but eventually moved into diamond mining — a business which, according to Oriel College, he excelled in, going on to found and head the global giant De Beers. Needless to say, he didn't achieve this by playing fair with his rivals. Rhodes and other business owners built up their profits by buying out farmers with small holdings, replacing them with huge industrial mining compounds. The conditions inside have widely been seen as cruel and exploitative. Workers were segregated by skin color and often locked into their living and working quarters until their contracts were at an end, facing restrictions on their personal lives such as being forbidden from bringing alcohol in.

However, writers such as Nigel Biggar from the publication History Reclaimed have insisted that this is only part of the story. Rhodes built villages where schools, churches, and fruit farms were provided for his workers. As a result, he was seen as a popular employer and one whom Black Africans traveled miles to work for. Biggar further states that the prohibition on bringing alcohol into the compounds was a result of excessive drinking among different groups in the Cape, itself a result of the colonial government suppressing warfare between different ethnic groups, leaving many men unemployed.

Whether or not outsiders should meddle in other states' conflicts is a delicate issue. But it would seem that "Rhodes the patronizing racist" was at least occasionally laced with "Rhodes the paternalistic racist."

Wider business dealings

As well as diamonds, Cecil Rhodes' major commercial interest was the gold exploited by colonial forces in the Cape Colony from 1886, as highlighted by Historic UK. By the time he was 28, Rhodes had become extremely rich, essentially having done the late-19th-century equivalent of investing early in bitcoin. By the time he was 34 he had amassed a fortune of £200,000 (over £18 million today, according to the Bank of England) due to his almost complete control of the Kimberley diamond fields, combined with £300,000 (over £27 million) from his investments in gold, probably making him seem like the world's biggest, mustachioed magpie.

Rhodes used his wealth to acquire more territory and military muscle to defend it, often by using underhanded tactics such as bribing local chiefs. This was during the Scramble for Africa, the name given to the period where mainly Britain, France, and Germany decided they had the right to march into other parts of the world and claim ownership. The people who lived there generally weren't consulted.

One of Rhodes' most notable conquests for Britain was Matabeleland, an area he entered with soldiers and turned into Northern and Southern Rhodesia after some considerable haggling — which was at least more courteous than simply turning up and forcing people to concede at gunpoint. Via the British South Africa Company (BSAC), a corporation he founded, he ultimately expanded British imperial territory by 450,000 square miles. It was an achievement, after a fashion.

The founder of apartheid?

You would have thought this might have left Cecil Rhodes a relatively content man. Yet political office soon beckoned. From 1890 to 1896, Rhodes was prime minister of the region known as the Cape Colony (part of modern-day South Africa). His government introduced legislation that raised the bar for voting to those who met the right financial criteria — a move that effectively disenfranchised Black people, who often lacked the wealth and status of their white neighbors (via the BBC). A more complex and sinister form of oppression was introduced in 1948, known as apartheid.

Rhodes' role in this is perhaps more complex than it would seem on the surface. A "color blind" set of voting rights had already been implemented in the Cape Colony since 1853, and Rhodes was against completely abolishing it in the way the imperial government was agitating for. Instead, he advocated for a system where the franchise was extended to those residents of color whom he regarded as "civilized," e.g., those few who were literate, worked, and owned property, and not to those who lived in communal settlements. History Reclaimed points out that at the time, the vote was only available to 28% of the population in Britain, so the idea of people needing to be "fit" to vote was commonplace. The picture was further complicated by Rhodes' statement that he could "never accept the position that we should disqualify a human being on account of his color," per the BBC.

His capacity for violence was less of a gray area.

The Jameson Raid

One of Rhodes' most controversial moments was his support for the Jameson Raid, a failed attempt in 1895 to overthrow the Afrikaner government of the Transvaal Republic headed by Paul Kruger (via the BBC). Rhodes blamed Kruger for stopping him building a railway line through South Africa. He also wanted those who owned gold mines in the republic, many of whom were British, to have a greater say in economic policy. Many "uitlanders," or outsiders, were denied citizenship by Krugman, who was keen to maintain the region's Boer identity and hold onto independence. As described by ThoughtCo, Krugman also sought to take over nearby Bechuanaland, a move that would have violated the 1884 London Convention, a treaty between the British Government and the Transvaal.

As Krugman dug his heels in, Rhodes became more impatient. He commissioned his friend Leander Starr Jameson to lead a military incursion of about 600 men, many of whom were poorly armed volunteers. The Boer Commandos quickly overcame them and Starr's men were sent back to Britain for trial, resulting in fines and prison sentences. Rhodes' British South Africa Company was forced to pay nearly £1 million to the Transvaal government, and Rhodes was forced to resign as Cape Prime Minister. (In fine British establishment style, Jameson only served four months out of a 15-month sentence).

Devastatingly, according to History Today it prompted the second Boer War between 1899 and 1902, which led to nearly 100,000 deaths, as well as the absorption of the Transvaal Republic into the British Empire, per Britannica.

Cecil Rhodes and the Ndebele

You'd think the Jameson Raid would have at least been seen as a warning. Yet rather than curbing his lust for conquest, Cecil Rhodes continued to forge ahead. The Boers were not the only ones to raise a few objections.

Rhodes' policy of negotiating deals with African rulers to gain access to mining reserves would often result in the violent annexation of their territory, sometimes in violation of formal treaties, according to Oxford. Yet in 1896, Rhodes' forces were resisted violently by the Ndebele peoples in what is now Zimbabwe. British forces had already been in conflict with the Ndebele in 1893, and the latest uprising involved similar tactics: mass killings of soldiers using the Maxim gun, raiding of grain and cattle stores, the desecration of crops, and the hanging of supposed rebels without trial. Oxford academic William Beinart highlights how civilians hiding in caves were blown up by dynamite by members of the BSAC.

At least 2,000 Africans and around 364 colonial troops and settlers died when Rhodes' forces suppressed the second rebellion. The total number of Africans who died during the military campaign in Zimbabwe in the 1890s is as high as 25,000. Rhodes' defenders have argued that part of his motivation was to prevent the Ndebele from violently conquering the Shona peoples; yet British tactics were considerably more brutal and pervasive, affecting the whole region and its peoples in a way Ndebele conquests had not. And Rhodes endorsed it. Somehow, that part never makes it onto any of the statues.

World domination?

Cecil Rhodes' actions were rooted in his belief that Britain contained an innate superiority placing it at the top of the racial and global pecking order. As a result, he was an unswerving apologist for the idea that British culture, values, and industry needed to be spread as far and wide as possible. He believed in particular that African societies were backwards, chaotic, and violent — something that could only be cured through imperialism, as expressed in his statement: "Why should we not form a secret society with but one object, the furtherance of the British Empire and the bringing of the whole world under British rule, for the recovery of the United States, for making the Anglo-Saxon race but one Empire?" (via iNews).

Even if his views were common in Britain, the Empire was a complicated endeavor. For some it was undertaken with the aim of securing land and resources to feed British industries. For others it was about converting people in the colonies from a narrow and stereotyped form of perceived "barbarism" to "civilization." These interests were sometimes in conflict, and so the ideology of the "civilizing mission" was not as widespread as you might think. Rhodes' supporters have pointed out that his investment in a South Africa — and if he'd lived longer, a whole world — united under his supposedly benevolent brand of imperialism (as opposed to building a McMansion) was a sign that his rampages were civic-minded rather than materialistic.

Handing out medals to someone for not flaunting their ill-gotten bling might seem like clutching at straws, given that he did fund one or two statues of himself (see below). But in a strange way, Rhodes thought he was doing the right thing. The road to hell and all that...

Individual relationships

On a day-to-day level, Cecil Rhodes' attitudes toward race were complicated. He was polite and respectful when trying to court powerful African leaders, particularly members of the Zulu group, when he needed their favor to expand his territory. According to Oriel College, despite the blood-letting that happened on his watch, he was involved in a number of peace-brokering initiatives. These included negotiations with Ndebele chiefs in 1896, and his decision to distribute £50,000 worth of grain to the Ndebele for famine relief. To add to this, he was charitable enough to allow some of the subjugated Ndebele to live on his newly acquired land, even marking this with a celebratory feast. When Rhodes died, the local chiefs he had forged relationships with invoked the terms of the agreement to try and prevent white settlers from encroaching on their land.

Rhodes also helped to finance a newspaper, the Izwi Launtu, that had a largely Black African readership — including the activists who laid the foundations of the African National Congress, the political party that ushered in post-apartheid South Africa under Nelson Mandela.

History Reclaimed argues that although Rhodes saw African societies as inferior to Britain, his views were based on some of the cultural practices he observed, not on the idea that Africans were biologically less developed. He was therefore open to treating Africans as equals — when it suited him. For Black people, it probably came to the same thing in the end. Some escaped his violent incursions, but many did not.

Rhodes scholars

Cecil Rhodes died of a heart attack in 1902 at the age of 49. His final words, as cited by Historic UK, were reportedly "so little done, so much to do." With his final breath, the rest of the world, particularly the parts left untouched by his megalomania, breathed a sigh of relief (probably).

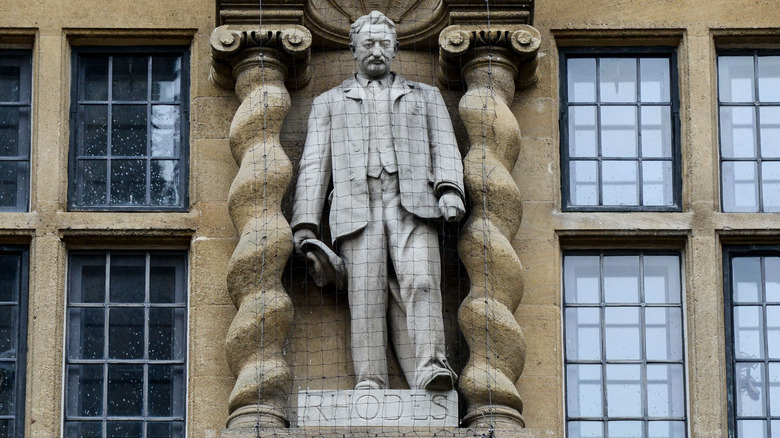

According to Oriel College, of the £100,000 that was left to them in his will (around £8.5 million in today's money), £40,000 was used to bankroll the erection of a new college building on Oxford High Street and to cover college expenses. The rest was left to fund various educational projects, known as "Rhodes Scholarships," which are the oldest of their kind in the world, per The Guardian. It is an aspect of his legacy often cited by his defenders, as Rhodes Scholars often come from impoverished backgrounds, often in former British colonies.

Some would argue that the Rhodes Scholarships symbolize an unequal relationship — a constant reminder to students of color that they have benefited from the largesse of a paternalistic white imperialist. And given the eye-watering fees Oxford charges for international students, people from poor backgrounds seeking an Oxford education perhaps can't afford to be picky. In light of how many of their forebears he helped obliterate, perhaps Rhodes' will could be seen as reparations to those from the former colonies — even if a small number of people benefit. Still, you take what you can get.

Lasting infrastructure

Cecil Rhodes' supporters have argued that he used his immense wealth for public rather than personal gain, within Africa as well as in Britain. Instead of building huge houses for himself, he lived relatively frugally, focusing his energies on establishing the fledgling mining sector, reforming South Africa's banking system, promoting agriculture through fruit farming, and building networks of telegraph communications and roads, as cited by History Reclaimed.

His beloved British Empire also left behind a political infrastructure that is still used in South Africa today. Journalist Will Hutton has argued that the "legacy institutions" of the Empire have benefited present-day South Africa in its battles against corruption, including "courts, rule of law, free press, [and] freedom of association and expression." The ability of the country's citizens to rely on these as they protest against the government are examples, according to Hutton, of the "liberal constitutional foundations which the appalling imperial supremacist and diamond racketeer helped lay."

As the son of a minister, Rhodes' own brand of evangelistic zeal means he would have had more in common with the missionaries who traveled to Africa under their own steam rather than other, more money-driven imperialists. This side of his legacy can't be ignored — yet it doesn't cancel out his more brutal views on imperialism, and what he did with them.

Cecil Rhodes' controversial afterlife

Cecil Rhodes' track record as an agent of colonialism has led to calls for his statues to be torn down, spearheaded by the campaign "Rhodes Must Fall." The Guardian reports that his statue in Cape Town was decapitated and removed, but the one outside Oriel College, erected in 1911, has stayed unblemished, with the university opting instead to put up a plaque mentioning the debate. This was predictable, since distancing the college from Rhodes' legacy could damage its relationship with present and future donors.

The decision to pull down other statues, like Saddam Hussein's in Iraq, is perhaps a sign that monuments lionizing violence and egomania need to go. Others have argued that Rhodes was a "man of his time" with a complicated legacy and shouldn't be judged by modern standards — even though as far back as 1906, alumni of his college were against the gluttonous imperialism that a statue of him might promote (per Oriel College Archives). Journalist Will Hutton (per The Guardian) contends that symbols matter, but they can't be the only target when other factors play a role in present inequalities. Rhodes' attitudes were widespread, and placing the blame on one person risks ignoring systemic forms of racism rooted in the past.

He may have died over a century ago, yet for better or worse, Rhodes has never seemed more alive.