Famous Historical Events That Are Mostly Made Up

The problem with history is that it's recorded by people, and people aren't the most credible witnesses. Over the years, some stories get retold, distorted, and embellished, until the tale that remains barely resembles the original event. No one can really be sure how many of history's most famous tales are mostly lies and misconceptions, but historians have managed to identify at least some of the most blatant offenders.

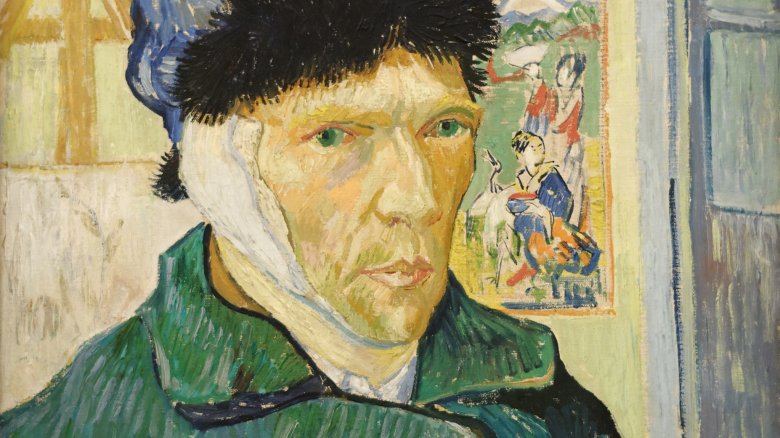

Vincent Van Gogh sliced off his own ear

Besides starry nights and fields of wheat, Vincent van Gogh is famous for being a little ... quirky. In his most notorious act of uber-quirkiness, the Dutch painter supposedly sliced off his own ear in a fit of madness, then took the world's most bizarre selfie (above): Self Portrait with Bandaged Ear. The story includes fun details like the prostitute who fainted when Van Gogh presented her with his severed ear because nothing says lovin' like something that was once attached to your body and is now wrapped up in a bloody piece of fabric.

For some reason, this tale is beloved — which is probably why it took so long for someone to call BS. According to Hans Kaufmann and Rita Wildegans, a pair of German historians, there is evidence that the entire story was fabricated by van Gogh's friend Paul Gauguin, who was probably the guy who actually chopped off the unfortunate organ (and by the way, it wasn't the whole ear, just part of the lobe). The original story came almost entirely from Gauguin and contains a lot of inconsistencies, plus there are loads of hints in letters that passed between van Gogh, Gauguin, and various other individuals alluding to the falsehoods of the story, including the damning statement, "I will keep quiet about this and so will you." Although the original story is less boring, it does seem likely that the tale of madness was fabricated to protect Gauguin from prosecution.

Sir Walter Raleigh introduced potatoes and tobacco to the British Isles

European explorers often took credit for stuff they didn't actually do, like "discovering America." They took credit for other, smaller innovations, too, like the introduction of potatoes and tobacco to the British Isles, both of which were supposedly gifted by dashing explorer/Queen Elizabeth I's crush Sir Walter Raleigh. Legend says Raleigh planted potatoes in Ireland on his way back from Virginia, because after weeks at sea there's nothing so relaxing as a little manual labor in a place where it hardly ever stops raining. He might have liked eating potatoes (maybe, you never know), but Raleigh never actually went to Virginia.

As for tobacco, one of Raleigh's servants is said to have thrown water on him while he was smoking a pipe, which is pretty logical since normal, non-combusting humans don't tend to have smoke coming out of their noses and mouths. But that alone isn't enough to credit Raleigh with tobacco's arrival in Britain. According to Historic UK, it's likely that pipe-smoking was adopted by British sailors as early as 1565, more than 20 years before Raleigh's travels. He probably did have some hand in popularizing the habit at court, but whatever – no one at the Tudor court was expected to live very long anyway.

Thomas Edison invented the light bulb

Thomas Edison invented the tin foil phonograph and the first motion picture camera, but he didn't invent the light bulb. Credit for the first actual light bulb goes to British scientist Warren de la Rue, whose invention failed mostly because he used coiled platinum as a filament, which was sort of like inventing a car that runs on gold coins and Grandma's heirloom silver. It wasn't until 1860 that someone invented a cost-effective light bulb, but that wasn't Edison, either — it was a British chemist named Joseph Swan. Swan's bulb looked good but burned out quickly, which meant it wasn't very practical for day-to-day use. Edison merely improved on those other inventors' ideas by replacing Swan's carbonized paper filaments with a thinner, more electrically-resistant filament, an idea that Swan promptly copied for use in his own bulbs. Edison sued him for patent infringement, and then the two inventors settled their differences in the American way, by merging their two companies to become a big powerhouse.

Jesus was born on December 25 in the year 1 A.D.

Everyone knows Christ was born on Christmas, as snow fell and the angels sang Silent Night. Except of course that it almost never snows in Bethlehem and Silent Night wasn't written until 1818, but never mind. That's not the only thing about the birth of Jesus that's likely incorrect.

The truth is no one really knows when Christ was born, but it almost certainly wasn't on December 25 and it was probably not even in 1 A.D. Estimates put the actual year somewhere between 2 and 6 B.C. (That's right, Christ was probably born before Christ. Figure that one out.)

A few scholars have tried to pinpoint the actual date by looking for celestial events that could have appeared as an unusually bright star — for example, on June 17, 2 B.C., Jupiter and Venus occupied the same part of the sky and would have looked like a single, exceptionally bright point of light.

Historians believe the church later chose December 25 not because anyone thought it was Christ's birthday but because they wanted to hijack holidays already popular with the pagans they hoped to convert. December 25 was close enough to the Roman festival of Saturnalia and the pagan celebration of the winter solstice that it seemed as good a day as any, and lo, that's why December is the month where we all max out our credit cards and fist-fight each other for the latest hot toy that manufacturers intentionally didn't make enough of. Oh, holy night.

300 Spartan warriors held Thermopylae against the Persians

It may shock you to hear that 300 Spartan warriors did not, in fact, single-handedly hold Thermopylae against the Persians. What's more, it also didn't happen in uber-slow motion, nor was the world soaked in weird, high-contrast sepia tones. Sorry.

According to ThoughtCo, the only truth in this story is that there were in fact 300 Spartan warriors defending Thermopylae. And it's probably true that they had six-packs, just as the popular 2006 movie promised. But what filmmakers forgot to mention is that there were 4,000 other people there, too, and 1,500 who made that fateful last stand. Now granted, this wasn't a whole lot of muscle compared to what the Persians had, but it wasn't just 300 super-ripped dudes, either.

So where did the whole "300" legend come from? At one point, as the battle was looking more and more iffy, the Greek king ordered everyone but the 300 Spartans and their slaves (which also numbered about 300) to retreat. Not all of them did, though, and on the last day of the battle there were 1,500 men left, or five times as many as the legend says there were. They still got their butts kicked, so maybe it doesn't matter.

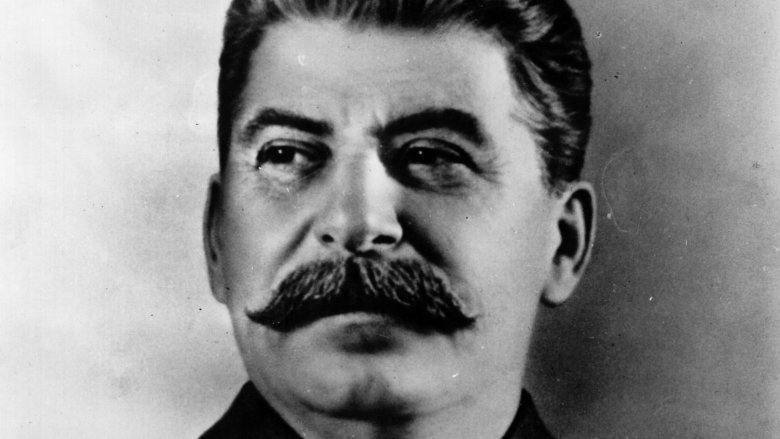

Stalin died peacefully in bed of natural causes

Pessimists love to remind us that crime pays and that there's no such thing as karma. To illustrate this eternally depressing argument, they will often point to the death of Stalin, exterminator of 20 million people and master of the pointy mustache, who after 30 years of tyranny died peacefully in his bed — or so sayeth the story.

Just over a year before his death, Stalin had his personal doctor arrested for suggesting that he "take things more easily." Not long after that, a bunch of other doctors were arrested for unclear reasons, so there really wasn't much eagerness in the Soviet medical community when it came to preserving Stalin's health. When he was found lying incoherent in a puddle of urine in March 1953, he was moved to a sofa and left alone. When doctors were finally called in, it was too late to help him, and he ended up dying slowly over three days, apparently in great pain. His daughter recalled, "The death agony was terrible. He literally choked to death as we watched."

There is even some question as to whether or not Stalin's death really was from natural causes — according to History of Russia, the medical report noted "extensive stomach bleeding," which is consistent with rat poison. So really, the only fact in this legend is that Stalin was actually in bed when he died. But that's about it.

Betsy Ross sewed the first American flag

Sorry kids, but that story you heard in kindergarten about Betsy Ross and the first American flag is probably not true. Yeah, she did sew a few flags. But the evidence that she sewed the first flag comes directly from the claims of her descendants, and you know how descendants can be when it comes to making grandma look like a Revolutionary War hero.

The most damning evidence against Betsy's involvement in the design and production of the first American flag is not in the stories themselves, but in the fact that no one ever mentioned her name in association with the first flag until almost 100 years later, when her grandson finally decided to inform the Historical Society of Pennsylvania. But there is no physical evidence supporting his claim — the information can't be found in any historical letters or newspaper reports, and there was no bill of sale or official record of any flag-designing liaison between George Washington and Betsy Ross.

Sadly, it's likely that the story was either totally fabricated by her grandson and his family or was a misinterpretation of details passed down over the course of a century. One fact about Betsy Ross that is true: she's one of only four American historical figures who got to become a Pez dispenser. Cool.

The First Thanksgiving

Grade-school plays are the gold standard for historical accuracy, and generations of grade-school plays have made it clear that the first Thanksgiving was pretty much exactly like the one we celebrate today, except everyone wore black, flat-topped hats and giant silver buckles.

Sorry, first graders, but Thanksgiving did not actually go down like that at all. For a start, there were no giant silver buckles and no one wore black. Black was a color reserved for Sundays and special occasions, and buckles weren't cool yet. Even if every Pilgrim teenager had been actively pining for a giant silver buckle, they were expensive and Pilgrims were pretty practical, so those Pilgrim teenagers would have all been huffing off to their bedrooms in disappointment.

Also, the first Thanksgiving wasn't actually called "Thanksgiving," it likely happened in late September, and it didn't officially become a thing until 1863, when Abraham Lincoln finally got around to telling everyone to Thanksgive like good folks. As for the meal, there's no proof that turkey was served, though it was probably somewhere on the table, along with ducks, geese, swans, and venison. Conspicuously absent: mashed potatoes and cranberry sauce. Potatoes weren't eaten in Massachusetts at that time, and even if it had occurred to someone that cranberries were delicious when boiled with sugar, the Pilgrims didn't have any sugar because, like true Americans, they'd already eaten all the sugar that came with them on the Mayflower.

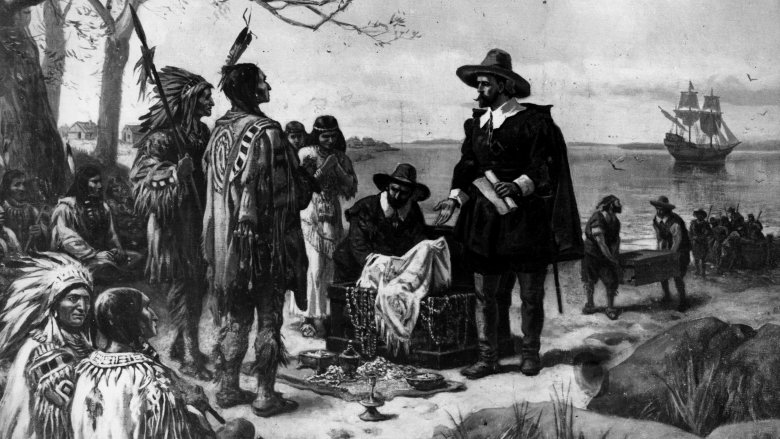

The Dutch bought Manhattan for $24 in beads

No one doubts that Europeans did some bad, bad things to America's original occupants, and the story of how the Dutch West India Company swindled the native people of Manhattan for $24 worth of beads is one of many tales often told to prove the point. But there's only one sentence written in the historical record about that particular transaction, and it reads like this: "They have purchased the Island of Manhattes from the savages for the value of 60 guilders." Nowhere does it mention beads. You could turn 60 guilders into $24, though ... if you were alive in 1846, which is when a New York historian first did the math, 200 years after the deal. (That figure in today's dollars is more like $740.)

Now, 60 guilders is still a bargain, especially when you consider that a studio apartment in modern downtown Manhattan will run you around 182 guilders a month. But that's not even the punchline. The punchline is that the Dutch West India Company bought Manhattan from the wrong tribe. The Canarsees, who ultimately pocketed the 60 guilders, didn't even live on Manhattan — they just hung out there occasionally. The island actually belonged to the Wappingers, who were not cool with the Dutch giving their $740 to a bunch of squatters. The Dutch had to buy Manhattan a second time, but no one knows what the Wappingers asked for because that information was never written down.

Only one Texan survived the Alamo

Perhaps the only story more beloved in American history than the one about Betsy Ross and the flag is the one about the Alamo. And while it was true that there was an ugly siege there and that there weren't a whole lot of survivors, a lot of the details were fabricated, mostly just to add a little romance to the legend. For example, Col. William B. Travis never drew a line in the sand and told the garrison to cross it only if they were willing to stay and fight. That story was made up by William Zuber, who wasn't even there. And contrary to reports that there were 180 defenders, the number was really more like 250 — 180 is just the body count inside the Alamo itself, and there were at least 60 more bodies outside.

Stories of lone survivors are always fun, but at least 20 people survived at the Alamo — and there were some men among the women and children. Finally, despite the persistent myth that 600 Mexicans died during the battle, the actual number was more like 60. But everything's bigger in Texas, right?

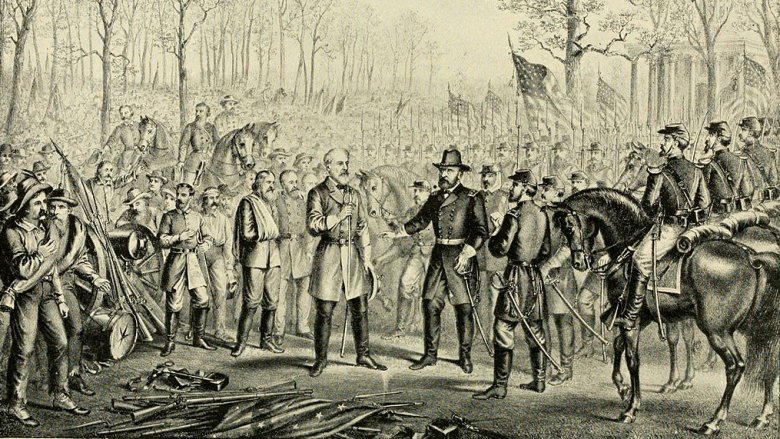

Ulysses S. Grant refused to accept Robert E. Lee's sword in surrender

Speaking of romance, no war in the history of war is quite as romanticized as the Civil War, which was actually a bloody, brutal mess that claimed the lives of 2 percent of the American population. And yet, we Americans love to hear tales of the chivalry and mutual respect between both sides, probably because it's hard to imagine that America could have ever been so divided, right?

Anyway, one of the most enduring stories is the surrender of Robert E. Lee. The popular version says Lee presented his sword to Ulysses S. Grant, but Grant gallantly refused to accept it. The origins of the story aren't known, but it's been circulating almost since the day Lee surrendered, because Grant himself felt compelled to set the record straight when he told the story in 1885: "The much talked of surrendering of Lee's sword and my handing it back, this and much more that has been said about it is the purest romance." And although this is all the evidence we need to dispute that particular moment of gallantry, he did also say, "I felt like anything rather than rejoicing at the downfall of a foe who had fought so long and valiantly, and had suffered so much for a cause, though that cause was, I believe, one of the worst for which a people ever fought, and one for which there was the least excuse." Those are not exactly words of praise, but at least some evidence of respect.

Women were burned at the stake during the Salem witch trials

Witch-burning is something that actually happened, but only once in America and not at all during the Salem witch trials. (Supposedly the only person burned as a witch in the United States was Leah Smock, but there was no stake involved. A posse locked her in the smokehouse on her family's farm and burned her alive, which is just as mean.)

Twenty people were convicted of witchcraft in Salem, Massachusetts, but they weren't all women and none of them ended up as special guests at the world's most unappetizing cook-off. Instead, most of them were hanged, which still sucks but isn't quite as gruesome (or painful). The lone defendant unfortunate enough to die a slower death was Giles Corey, an elderly man who refused to dignify the whole stupid charade and got pressed to death beneath heavy stones because he wouldn't say whether he was innocent or guilty.

The British defeated the Spanish Armada

Before you get your bloomers in a twist, yes, it's true that the Spanish Armada was defeated in 1588. And yes, it's true that if the Spanish Armada had not been defeated, there might have never been a British Empire. (Quite honestly, that wouldn't have been so terrible for places like India and South Africa, but whatever.) The facts of the story aren't that Britain defeated the Spanish Armada in a flurry of cannon-fire and strategic genius — no, the British just got lucky.

Of the 129 ships in the Spanish Armada, the British destroyed only six of them, mostly because Britain was broke and didn't have enough gunpowder to take out the whole fleet. At least 50 ships were lost in a storm, which arrived just in time to make things difficult for the Spanish. As the armada went limping back to Spain, a bunch of sailors died from starvation, thirst, and disease. So by the end of the battle, the Spanish fleet was a pretty pathetic thing, but it wasn't the British who made it that way — it was bad luck and the weather.