The Untold Truth Of Dr. Jane Goodall

In 2013, The Guardian asked Jane Goodall to recall her earliest memory. She answered, "When I was two, a dragonfly flew near me. A man knocked it to the ground and trod on it. I remember crying because I'd caused the dragonfly to be killed." Decades later, the girl who wouldn't hurt a dragonfly became a world-renowned conservationist, encouraging compassion for all living things through projects like Roots & Shoots and the Jane Goodall Institute. But she's primarily known for monkeying around with primates.

Goodall drastically impacted how humans view chimpanzees via visionary research she conducted in Tanzania. But it wasn't easy. In many respects, her success was improbable and probably says more about her strengths as a person than it does about the power of scientific insight. Her story is surprisingly inspiring and shows that Goodall the woman deserves just as much notice as the apes she's famous for studying.

Tarzan's other Jane

Anyone who's been in love knows that it doesn't just give you a feeling — it gives you a purpose. Jane Goodall discovered her purpose after falling for a jungle hunk. As the book, "Jane Goodall: A Biography" describes, Goodall adored Tarzan as a child. In her words: "I was madly in love with the Lord of the Jungle, terribly jealous of his Jane. It was dreaming about life in the forest with Tarzan that led to my determination to go to Africa, to live with animals and write books about them."

When she wasn't swooning over ape-men, Goodall was fawning over fauna. For years she had watched animals with insatiable wonder. That wonder caused worry when she hid in a hen house to observe egg-laying. Goodall's family, unaware of her zoological peeping, thought she had gone missing. Other habits were less harrowing, like repeatedly reading Doctor Doolittle and holding unironic snail races. Even Goodall's social interactions involved animals. At age 12, she created the Alligator Club, which, according to Biography, required members to memorize 10 varieties of dogs, birds, and trees, and five kinds of moths or butterflies. In a separate endeavor, she raised money to help save old horses from becoming new horse meat.

Animals also saved her. As a British child who lived through World War II, Goodall discovered man's inhumanity at a young age. Wildlife became her refuge, an Eden amid the evil. Nature wasn't just a plaything; it was everything.

Jane Goodall, the ape woman

Philosopher of science Thomas Kuhn once famously asserted that "under normal conditions, the research scientist is not an innovator but a solver of puzzles" and that such puzzles are examined "within the existing scientific tradition." When Jane Goodall first researched chimpanzees, the scientific tradition maintained that nonhuman primates were deeply primitive. But Goodall wasn't a traditional scientist, and the circumstances surrounding her work were far from normal.

As the BBC reported, Goodall journeyed to Kenya in 1957 without any intention of studying chimps. Her idea of Africa was about Tarzan the ape-man, not actual apes. According to Biography, that changed after some friends introduced her to paleoanthropologist Louis Leakey, who saw in her the makings of a great ape investigator. Under Leakey's tutelage, Goodall began observing chimpanzees in 1960.

After some early hiccups, Goodall made a pair of pivotal discoveries. Contrary to prevailing beliefs, chimps weren't simian simpletons who couldn't use tools, and they didn't shun meat like hairy hippies. They used grass (like hairy hippies) to hunt insects and ate pigs because pork was delicious. At Leakey's behest, Goodall reluctantly pursued a Ph.D. at Cambridge despite not even having an undergrad degree. The academic outsider outshined her colleagues by uncovering the social lives of apes. She chilled with Tanzanian chimps in trees, mimicked their behaviors, and established the "Banana Club," which fostered banana-based bonding. The chimps welcomed her and her tasty fruit. Like Doctor Doolittle before her, Goodall talked with the animals, and the animals responded.

The visionary's vision problems

For all of Goodall's good fortune, she also had her struggles. One of the biggest obstacles she faced was her own brain. As The New Yorker explained, the revolutionary researcher suffers from prosopagnosia, also known as face blindness. Commonly caused by damage to the brain's fusiform gyrus, the disorder limits or completely impairs a person's ability to recognize faces. For Goodall, it makes unremarkable faces extra forgettable. As she put it, "I have huge problems with people with 'average' faces. ... I have to search for a mole or something. I find it very embarrassing! I can be all day with someone and not know them the next day."

Prosopagnosia also interfered with Goodall's research. When trying to keep track of a chimp troop, it obviously helps if you can tell the members' faces apart. However, Goodall could only manage to do this after becoming well acquainted with them. To further complicate matters, she's apparently also plagued by place blindness. As she described, "I just don't know where I am until I am very familiar with the route. I have to turn and look at landmarks so I can find my way back. This was a problem in the forest, and I often got lost."

Interestingly, Goodall later lamented ingratiating herself with chimps through banana bribes, which she believed altered the animals' natural habits. But given her face blindness, it seems fair to suggest that the practice was more fruitful than harmful.

[Featured image by Csigabi via Wikimedia Commons | Cropped and scaled | CC BY-SA 3.0]

Jane Goodall hits a wall

Sometimes science advances like an avalanche. Other times it's trapped on a treadmill. Goodall was an academic avalanche whose colleagues tried to tread on her work. Per the BBC, she often encountered condescension and ridicule. A contingent of vocal critics saw her as an academic pretender and accused her of fabricating findings. They derided Goodall's practice of naming the chimps she observed and dismissed claims she made about primate personalities as anthropomorphic folly.

Goodall tried to take these slights in stride, but certain indignities still stung. At a 1962 symposium, a prominent anatomist and science adviser for the U.K. Ministry of Defense flung verbal poop at Goodall's chimpanzee research. While giving a talk, he dismissed her observations as "unbounded speculation" and mocked her explanations, much to Goodall's consternation. In his mind, she should have aped the methods and assertions of past primate researchers. The novelty wasn't welcome.

Goodall's detractors began backtracking in 1965. As PBS explained, National Geographic spotlighted Goodall's revolutionary research in a documentary. Suddenly, she was a big deal. Critics had to stop treating her like a scholastic punching bag and start regarding her as the ethological heavy-hitter she was.

Nat Geo goes wild

Jane Goodall's claim to fame came with the 1965 documentary, "Miss Goodall and the Wild Chimpanzees." Produced by National Geographic and narrated by the iconic Orson Welles, the film featured Goodall's investigative exploits in Tanzania. It would fundamentally change how people perceived primates. According to National Geographic, the film also redefined what it meant to be a scientist. Goodall was "an attractive white woman doing scientific work in the African bush" during a period "when women typically were discouraged from pursuing careers in science."

In hindsight, it almost sounds like the stars aligned to make Goodall a star. But the documentary almost never happened. National Geographic first caught wind of Goodall through her mentor Louis Leakey, who had reached out in hopes that the organization would help finance her studies. However, it initially responded with the same spontaneous skepticism as Goodall's colleagues. Leakey refused to relent. He passionately championed his pupil and urged National Geographic to reconsider. The organization agreed to provide funding if it could send a photographer to document Goodall's doings.

The pictures that emerged were worth 1,000 wows. Impressed, National Geographic decided to make a documentary. This time Goodall took issue with the arrangement. The filmmakers insisted on crafting a heavily manufactured reenactment of her work. To vent her vexation, Goodall collected a bunch of scary spiders and centipedes to frighten off someone sent to oversee filming. Ultimately, though, all the unwanted editing altered her life for the better.

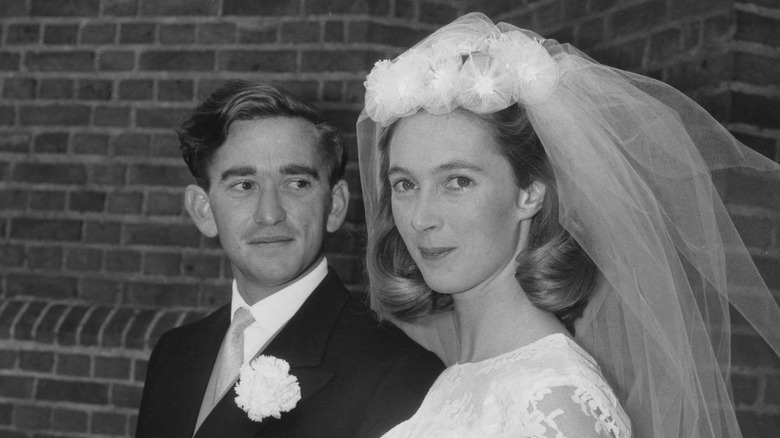

Miss Goodall becomes a Mrs.

Miss Goodall and the Wild Chimpanzees aired in 25 million households across North America. Countless eyes watched with wonder as science and camera magic wedded onscreen. Off-screen, the titular scientist and her cameraman had wedded in real life. Per National Geographic, photographer Hugo van Lawick (pictured) had been sent to shoot footage of Goodall's fieldwork and findings. Along the way, the two found each other.

Love had taken Goodall by surprise. When National Geographic first entered the picture, she objected to having pictures taken, fearing it would interfere with her work. Instead, her uninvited photographer captured her heart. It must have also been a shock for Louis Leakey, who had long ago professed his undying and wholly unrequited love for Goodall. By contacting National Geographic, Leakey had inadvertently placed his unattainable mentee on the path to marrying van Lawick.

In 1967, Goodall and van Lawick became the proud parents of a bouncing baby human. Seven years later, they divorced. Van Lawick had spent too long working abroad, and absence had made their hearts grow absent. But new love wasn't far off. In 1975, the year after her divorce, Goodall married Derek Bryceson. According to People, Bryceson was a former English airman who had helped Tanzania gain independence from Britain. To Goodall, he was something of a kindred spirit. He, too, had been "inexorably drawn" to the African continent. Their union lasted until 1980 when Bryceson tragically died of cancer.

Jane Goodall's worst moment in the wild

Nature is equal parts amazing and awful. It brims with beauty but also abounds with brutality. During her time in the wild, Goodall "withstood all manner of natural threats," according to National Geographic. She confronted wicked weather, perilous parasites, and snakes. She surrounded herself with chimpanzees, animals that dabble in cannibalism and engage in gang violence. But the worst thing Goodall witnessed was human cruelty.

Per The New York Times, Goodall's most traumatic moment in nature came courtesy of Zairean guerrillas. In 1975 –- the same year Goodall wedded her second husband –- 40 armed intruders stormed the Gombe Research Reserve, which she headed. The New York Times reported that the guerrillas assaulted staff members before abducting a group of Stanford University-sponsored researchers. The remaining visiting researchers escaped and were subsequently evacuated.

Just as it had during World War II, human conflict filled Goodall with fear and uncertainty. It would take two months for the captive scientists to gain their freedom. Moving forward, Goodall resolved to hire only Tanzanians to aid in her work. She didn't want to risk another kidnapping. The experience also seemed to reaffirm her desire to retreat from society. "I don't care two hoots about civilization," she declared. "I want to wander about in the wild.”

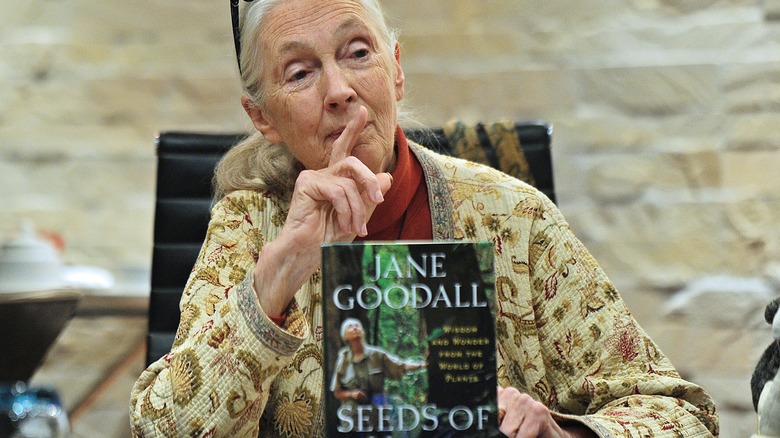

The seeds of controversy

Nobody's accomplishments are all good, not even Jane Goodall's. In 2013, her book, "Seeds of Hope: Wisdom and Wonder From the World of Plants," received tremendous attention for all the wrong reasons. Co-written with freelance writer Gail Hudson, the work took aim at genetically modified crops, citing various concerns about their safety. Unfortunately, the book's underlying flaws undermined the attempt.

As The Washington Post detailed, "Seeds of Hope" was rife with passages purloined from various websites. In at least a dozen different instances, everything from phrasal chunks to meaty, paragraph-long sections had been inserted into the book without proper attribution. Further worsening matters, the uncredited sources in question were often questionable. They included Wikipedia and sites about beer, tea, tobacco, and astrology.

Had the astrology site done its job, Goodall might have seen the controversy coming and nipped it squarely in the bud. Instead, she got blindsided as critics pegged her as a plagiarist. Goodall attributed the lack of attribution to her "hectic work schedule" and "chaotic" note-taking, according to The Guardian. Of course, if Goodall was that deep in other obligations, it's entirely possible that her co-writer Hudson may have done the bulk of the writing. That might also account for some of the bizarre sources. Hudson was a so-called "spirituality editor for Amazon" and advocated organic eating and "holistic living." However, Hudson refused to speak on the matter, and Goodall refused to implicate her.

The appalling mauling

Despite such pitfalls as pit vipers and pit-stain-inducing heat, the African wild has been Jane Goodall's oasis from humanity. But sometimes, oases need their own sanctuaries. Habitat loss and habitual poaching have decimated various animal populations, including those of chimpanzees. As part of a decades-long effort to aid her hairy brethren, Goodall founded the Jane Goodall Institute Chimpanzee Eden in South Africa in 2006. Per CBS, the sanctuary houses abused and orphaned chimpanzees.

Unfortunately, Chimp Eden has its own Tree of Knowledge, and in 2012 a tour group got a bloody bite of the apple. It happened swiftly and savagely. As The Guardian detailed, university student Andrew Oberle was interning as a tour guide when two chimps yanked him under a fence. Oberle's offense: encroaching on their territory. The angry apes had chucked a rock at visitors, and Oberle rather unwisely approached their enclosure to grab it. In response, they grabbed him.

The helpless human got manhandled by the apes. They dragged him half a mile and bit him to oblivion. St. Louis Magazine reported that the chimps "tore away his scalp down to the skull," destroyed his nose and ears, and did devastating damage to his right eye. His wounds proved so severe that he had to be placed in a drug-induced coma. Oberle's nightmare was made all the more bitter by the fact that he had dreamed of becoming a primatologist. Oberle ultimately survived but was permanently marred.

Jane Goodall's favorite animal

It's easy to think of Jane Goodall as a woman who simply pursued a passion for primates. Her favorite childhood toy was a stuffed chimpanzee. She has spent tireless, untold hours with the chimps and has striven to protect them from harm. By now, she probably even smells like them. But as Goodall herself has acknowledged (via the BBC), that wasn't some lifelong dream she harbored. When reflecting on her early days of research, she remarked, "I never wanted to be a scientist per se. I wanted to be a naturalist." In fact, chimpanzees aren't even her favorite animal.

That honor goes to dogs, according to The Globe and Mail. While Goodall obviously likes chimpanzees, she can't see past their inherent humanity. In her words: "My favorite animal is a dog. I love dogs, not chimps. Chimps are so like us: Some are nice and some are horrid. I don't actually think of them as animals any more than I think of us as animals, although both of us are."

Interestingly, Goodall attributed much of her scientific success to the time she spent with her dog Rusty as a child. As "Jane Goodall: A Biography" recounted, Rusty was her trusty companion. They explored the outdoors together and forged an indelible bond. Goodall taught Rusty tricks, and Rusty taught her "that animals have personalities, minds, and feelings of their very own." It's one of the best things man's best friend ever did.

She hasn't ruled out Bigfoot's existence

If Jane Goodall faced brutal criticism from other researchers just for using names instead of numbers in describing her chimpanzees, one wonders what more conservative scientists think of her opinion of Bigfoot. The legendary primate of the American Northwest has never been taken seriously by most primatologists or anthropologists. The rare exception, like Jeffrey Meldrum of Idaho State University, has had their credentials suspected and noise made about their position within institutions. Yet Goodall has consistently refused to rule out Bigfoot's existence.

"I'm a romantic," she told Yahoo Entertainment in 2018. "I would like Bigfoot to exist." It's the position she's held when asked about Bigfoot for years. Not that Goodall has never expressed some skepticism. But Goodall has spoken to many eyewitnesses who seem sure of what they saw and came across natives in Ecuador unaware of the Bigfoot myth who told her, through a translator, of tailless monkeys six feet tall. Goodall has, in various interviews, entertained the idea of Bigfoot as a surviving Neanderthal, or even a spiritual presence.

Goodall has never declared herself a firm believer, and skeptics aware of her interest have tried to rationalize it as a playful promotion of mystery. But Goodall's interest is strong enough that she provided a jacket blurb for one of Meldrum's books in 2006.

Jane Goodall was honored with a LEGO set

Jane Goodall has said that awards, while a nice show of recognition, don't do much for her. "I'd rather be given a little pressed flower by a small child who's pressed it for me because she loves me and wants to give me something to remember her by," she told Newsweek. "Those reach the heart." But that hasn't stopped companies, bodies, and nations from presenting her with honors. Her native Britain made her a dame in 2004, with the award presented by the then-Prince Charles. Disney, which has partnered with the Jane Goodall Institute on conservation efforts, paid her a tribute through the Tree of Life in their Animal Kingdom park in Florida. At the base of the tree is carved an image of the first chimpanzee Goodall studied, a male she named David Graybeard.

A more recent honor may not have been awarded to Goodall directly but is available for her and anyone else interested in having it in their home. LEGO offers a Jane Goodall Tribute set, made up of three trees, three chimps, and a LEGO likeness of Goodall herself.

She's maintained a religious feeling

Jane Goodall was raised in a Christian household. In her memoir, "Reason For Hope: A Spiritual Journey," she wrote that she enjoyed reading the Bible as a teenager. She also began reconciling a steadfast belief in God with the impossibility of certain biblical stories, like Eve being created from a rib or Creation taking a literal week. In 1974, while visiting the Notre Dame Cathedral in Paris, she found herself looking at the sunlit Rose Window of the almost-empty church when organ music began, setting off a mystical experience. "That moment ... was perhaps the closest I have ever come to experiencing ecstasy," she wrote. "Since I cannot believe that this was the result of chance, I have to admit anti-chance. And so I must believe in a guiding power in the universe — in other words, I must believe in God."

Goodall has continued to describe herself as a Christian, albeit in qualified terms. Against some conservationist critics who accuse the Bible of encouraging a destructive attitude toward nature, she's argued that the proviso in Genesis that mankind has "dominion" over the world would be better translated as "stewardship." But her spirituality, reinforced by her work with animals, sees God as beyond mortal comprehension. She's also shown an interest in efforts to reconcile science and spirituality; she wrote the forward to "The Intelligence of the Cosmos," an exploration of ideas of quantum consciousness by philosopher Ervin Laszlo.

She's made friends with the artist of The Far Side

In 1987, cartoonist Gary Larson was doing well. "The Far Side," his single-panel newspaper comic strip, was a strange yet popular send-up of human and animal foibles. But not everyone appreciated the strip's jokes, as Larson learned when the leadership of the Jane Goodall Institute took up arms over a strip about a chimp husband and wife arguing over the husband spending time with "that Jane Goodall tramp." Larson never intended the joke as an attack on Goodall, whose work he admired. But the institute's executive director had lawyers begin preparing action against the cartoonist.

The director, however, forgot to check with the institution's namesake. Goodall was in Africa when the strip first ran, but when she got her hands on a copy, she thought it was funny. "If you make a Gary Larson cartoon, boy you've made it," she told NPR years later. She was more offended by the director's outrage and intended to write Larson an apology before getting caught up in a tour. No legal action was taken, though it was arranged that the institute would receive proceeds from T-shirts featuring the cartoon. In fact, Larson and Goodall became friends after the controversy. She wrote the forward for one of his book collections, and he joined her on a 1988 safari. The trip was only slightly marred by an encounter with Frodo, an aggressive teenage chimpanzee who tried to push Larson around (presumably not over the cartoon).