The Untold Truth Of Triton, Neptune's Doomed Moon

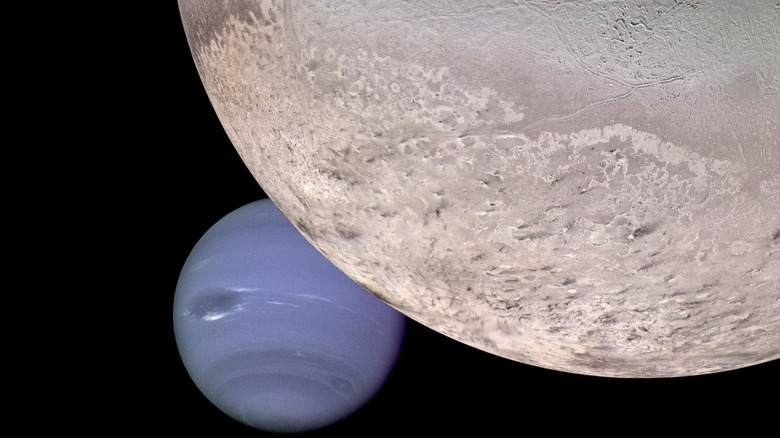

In 2022, the China National Space Administration (CNSA) announced its plans to send a spacecraft to planet Neptune. As the Planetary Society mentions, it has a launch date tentatively slated for sometime in 2024, and when it arrives, it will become only the second human-made vehicle ever to visit the Solar System's other blue planet. The ice giant Neptune, with its cerulean hue and raging storms, is the most distant planet from the sun. Ever since the flyby of Voyager 2 in 1989 gave a tantalizing glimpse of the cold world, scientists have talked about returning to learn more, as the Planetary Society notes. Sadly though, despite all of the plans and proposals, a NASA space mission to Neptune has yet to materialize. Perhaps even more interesting than Neptune itself, however, is Neptune's large icy moon, Triton.

Triton is perhaps one of the most overlooked places in the entire Solar System, going for decades before it was even given a name. Its discovery was first reported in 1847, by Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, but no name was even suggested until 1880, in the book Astronomie Populaire. Despite the apparent disinterest in it, though, Triton is easily one of the most mysterious places in the entire Solar System. As the Encyclopedia of the Solar System (via Science Direct) notes, Voyager 2's brief visit only showed around 40% of Triton's surface. Most of it is completely unknown. But what little is known is fascinating.

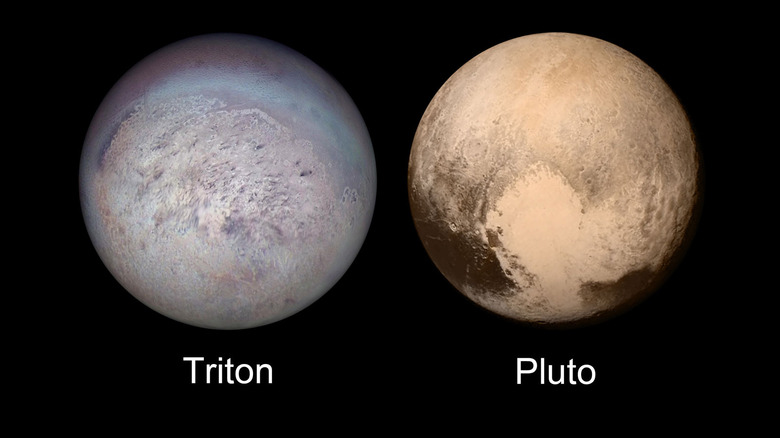

Triton is Pluto's captured sibling

Triton is orbiting Neptune in the wrong direction, and that raises a lot of questions in itself. Most people will know the word "retrograde" from their horoscope predictions but, in astronomy, it refers to the direction an object physically orbits another, going against the orbits of any other moons, and against the rotation of the planet itself. Triton's retrograde orbit suggests that it didn't form naturally around Neptune and, as NASA explains, it's a popular opinion that Triton is a captured object from the Kuiper Belt – the collection of icy not-quite-planets that drift through the Solar System's farthest reaches.

It turns out that Triton is surprisingly similar to Pluto. While the pair may look quite different, Britannica notes that they have roughly the same size and composition, which hints that they may have come from the same birthplace in the frigid darkness out beyond Neptune's orbit. The most likely story is that Triton's orbit once crossed paths with Neptune (a lot like Pluto's orbit still does) until it strayed too close to Neptune's gravity and got caught. Events like this are chaotic and, as Space.com mentions, both Neptune and Triton probably used to have other moons which were lost when Triton crashed Neptune's party.

Triton has ice volcanoes which erupt watery lava

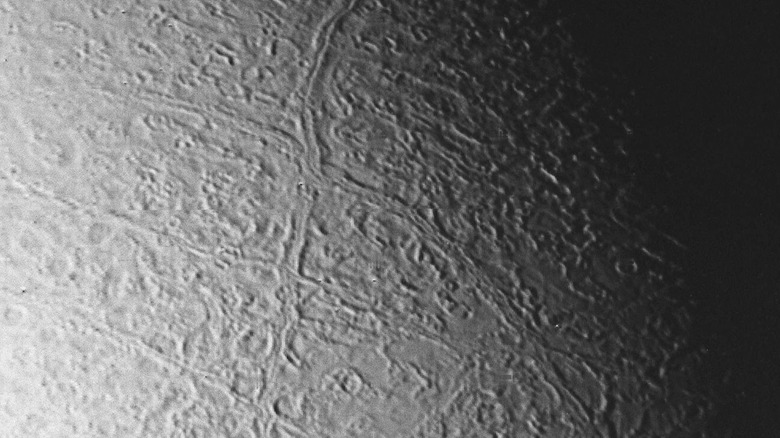

Being so far from the sun's warmth, the outer reaches of the Solar System are stunningly cold. On a world like Triton, water is frozen into ice so hard that it behaves in much the same way rocks do on Earth. Where Earth's crust has tectonic plates made of solid rock, Triton's tectonic plates are made of solid ice (via NASA) – and where Earth has volcanoes erupting molten rock, Triton has cryovolcanoes that erupt water. As a paper from the Lunar and Planetary Science Conference explains, Triton's surface appears to have volcanic terrain, with smooth lava flows, the solidified remains of lava lakes, collapsed lava tubes, and even some signs of explosive volcanoes from the past. The lava which sculpted these features was a lot thicker and more viscous than pure water, though. Seemingly, it's most likely to have been a mixture of water and ammonia, perhaps erupting as a kind of icy slush.

As well as cryovolcanoes, Triton is also home to geysers that shoot tall plumes of material high into the thin atmosphere, before raining back down to the surface. As NASA JPL explains, Voyager 2 even managed to capture photographs of an erupting geyser as it sped past. This makes Triton part of a select handful of places in the entire Solar System known to be volcanically active — alongside Earth, Venus, Jupiter's moon Io, and Saturn's moon Titan.

Triton has seasonal weather

Titan, Saturn's giant moon, is well known for its thick, hazy atmosphere, but it isn't the only moon in the Solar System with a veil of atmospheric gasses. Triton too has an atmosphere covering its freezing surface, but it's extremely thin compared to Titan, Earth, or even Mars. Surprisingly though, as a paper in Astronomy & Astrophysics explains, while Triton's atmosphere may be barely a whisper, it contains a troposphere — a turbulent lower layer where weather can occur, not entirely unlike on Earth. Another study, published in Science, notes that the winds in the thin Tritonian air can be seen from the way they blow on the plumes from Triton's geysers.

Triton's weather is surprisingly complex. As an article on Space.com explains, there are signs that Triton has seasons. In the summertime, Triton's atmosphere thickens as its surface warms and gasses start to evaporate, while in the Tritonian winter, snow can even fall from the cold little moon's skies. Unlike on Earth though, snow on Triton is most likely made from a mixture of nitrogen, methane, and carbon monoxide. And being so far from the sun, carried by Neptune's slow orbit, the seasons last for a long time. The summers and winters there last for 40 Earth years each.

Aurorae light up Triton's night skies

The polar regions on Earth are known for the spectacular aurorae which light up the night skies. As Discover Magazine explains, aurorae are caused by charged particles from the solar wind. As these energetic particles strike the atmosphere, they excite molecules causing the stunning light shows familiar to anyone living in polar regions. But Earth is far from the only place in the Solar System where aurorae light the skies. Astronomers have spotted aurorae on every planet except Mercury (which has no atmosphere). Discovering aurorae on Triton, however, took everyone by surprise.

A Washington Post article from 1989, shortly after Voyager 2 visited Neptune, explains how both Neptune and Triton show auroral displays in their skies. Scientists were reportedly so surprised by what they saw that they were hesitant to even call it aurora at first. Aurorae are usually caused by a planet's magnetic field pulling in solar wind particles, but, in the case of Triton, it's seemingly because the moon is orbiting in the midst of Neptune's magnetic field, crashing into charged particles swept up by Neptune's magnetism. With a hydrogen-rich atmosphere, Neptune's aurorae would most likely be a red color, but Triton's atmosphere is mostly nitrogen, just like Earth. This means that Triton's aurorae would be a familiar color to human eyes. Anyone standing on the surface of Triton would likely see a faint greenish glow lighting up the moon's dark skies.

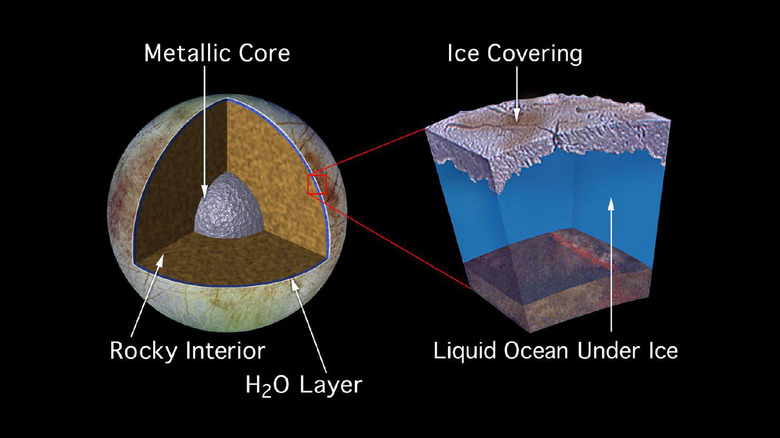

There may be a hidden ocean inside Triton

The outer Solar System's giant planets carry several icy moons in tow, and it's widely suspected that several of them might be hiding subsurface water oceans under their thick, icy shells. As NASA notes, Jupiter's moon Europa may even contain twice as much water as Earth has on its surface. Being mostly made of ice, Triton is a prime candidate as a place to look for one of these secret oceans. As Scientific American mentions, it's an especially promising target because it's so geologically active. With its cryovolcanoes and tectonic activity, Triton's heart probably contains a significant source of heat, which would help to keep its insides from freezing solid.

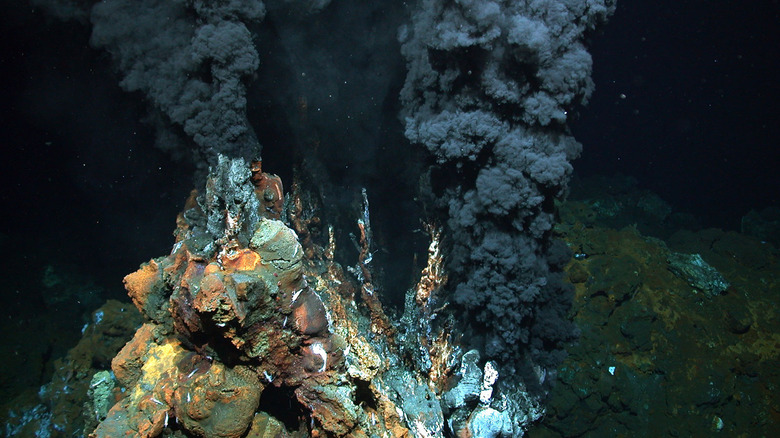

There are likely a couple of different things helping to keep Triton warm. A paper published in The Planetary Science Journal mentions an effect known as obliquity tides. These are caused because Triton has an axial tilt of around 30°, which means that as it orbits Neptune, the giant planet's gravity tugs and pulls at the moon's interior, causing friction that warms it up. Another factor, mentioned by Space.com, is the fact that Triton's core is made of rock. Like on Earth, that rock is full of heavy elements, including radioactive isotopes. As these decay, they release plenty of energy in the form of heat, causing an effect called radiogenic heating. These could even warm Triton's ocean via hydrothermal vents, like those on the ocean floor of Earth.

Something could be alive in Triton's hidden depths

Anyplace in the universe where liquid water can exist carries the tantalizing possibility of extraterrestrial life. On Earth, water is the one thing that all known life needs to exist (although science can't entirely rule out the possibility of life existing without it). As Astronomy Magazine explains, Triton's probable watery interior makes it a fascinating target for astrobiologists looking for life off Earth. While the moons Europa and Enceladus have garnered the lion's share of the attention about subsurface oceans and possible life, Triton is seemingly no less likely. And if living things can be found inside even one of these moons, that makes a compelling case that they could also be found in any of the others.

For now, with no way of seeing under Triton's cold, icy crust, there's no way to say anything definitive. As PhysOrg notes, this means that there's no way to rule out the possibility of life there, though the waters of Triton would quite literally be an alien environment compared to any on Earth. Triton's ocean would have a different chemical composition, with things like ammonia mixed in, which may mean that the liquid water there could be extremely cold compared to anything on Earth. But then, there's a chance that life in a place like Triton could have wildly different chemistry to terrestrial life, too, perhaps even being based on silicon compounds instead of the more familiar carbon of Earth life.

Triton is the solar system's coldest moon

Triton's icy terrain is, quite simply, the coldest surface that any human spacecraft has ever seen close up. As noted by NASA, the surface of Triton has an average temperature of -235°C (-391°F), which is cold enough to freeze nitrogen. Most of Earth's atmosphere is made of nitrogen gas, but liquid nitrogen, as Thought Co. explains, is famously cold enough to flash-freeze things. Needless to say, nitrogen ice is colder still. Surprisingly, the surface of Triton is even colder than Pluto, even though it's usually closer to the sun. Pluto's temperature averages -232°C (-387°F). Warmer, but not by much.

Because of its extreme cold, Triton's surface is encrusted with frost made from nitrogen. As NASA explains, this is another unique thing about Triton. It's the only moon in the Solar System with a surface mostly made from nitrogen ice, stained pink in places by carbon compounds in the feeble sunlight. Seemingly, one of the main reasons for Triton's extreme low temperatures boils down to its high reflectivity, with its bright icy coating bouncing most sunlight away into space, barely warming up the moon at all.

Triton is brighter than Earth's Moon

Triton really is extremely reflective! Sunlight is scarce so far out in the Solar System and, as NASA mentions, most of the sunlight hitting Triton's surface is immediately reflected away. The technical term for this is albedo, the measure of how reflective a given surface is — whether that surface happens to be the roof of a building or the icy crust of a moon. The higher the albedo, the less light a planet or moon absorbs, and the more it reflects back out into space. And being covered in brilliant ice, Triton is practically a mirror. An article published by Nature mentions that Voyager 2 took a measurement of Triton's albedo as it passed by. According to Voyager's instruments, Triton reflected 89% of the light striking it.

That 89% is a shockingly high albedo. By contrast, as a Scientific American blog post mentions, Earth's moon reflects only 12% of the light hitting it. A full moon on Earth may appear bright, but our moon is actually no more reflective than asphalt. If Triton were to appear next to the moon in Earth's night sky, it would shine about 7 times brighter.

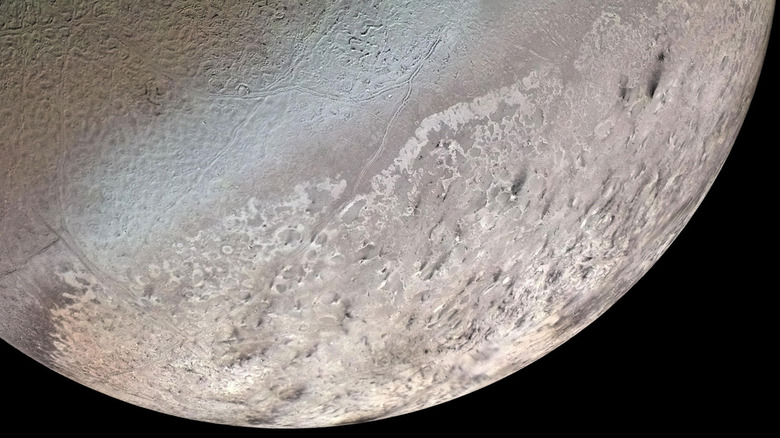

The surface of Triton looks surprisingly young

The Solar System is full of moons and planets which are covered in craters, from the hot stone surface of Mercury to the scarred icy plains of Callisto. Triton's surface, however, is one of the most youthful seen anywhere. A presentation at the 52nd Lunar and Planetary Science Conference even described it as "arguably the youngest surface of any icy body in the Solar System," attributing the secret of Triton's eternal youth to a combination of the nitrogen ice on its surface and the internal heat which helps to actively shape the moon's environment. A paper published in the journal Icarus even describe's Triton's surface age as "negligible." In other words, it's as good as new. Or at least, new for a planet. Some parts of Triton's surface are no older than 6 million years, which is barely anything at all on geological timescales.

Triton seemingly only has around 100 impact craters larger than 5 km in diameter, most likely caused by comets. As a study in Science notes, this is a scarce amount! Seemingly, all of Triton's craters are on its leading side, meaning that they were caused by objects Triton collided with as it orbits Neptune (like Earth's Moon, Triton is tidally locked, with the same side always pointing towards its adoptive parent planet). Interestingly, this also implies that there are no notable craters on Triton's surface from before it was dragged into Neptune's orbit.

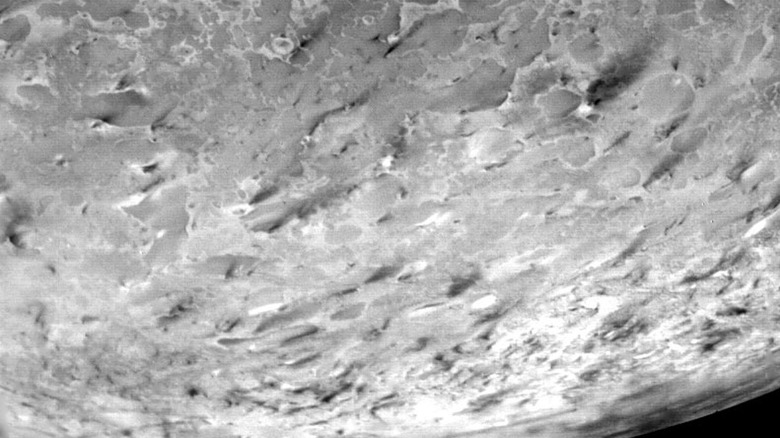

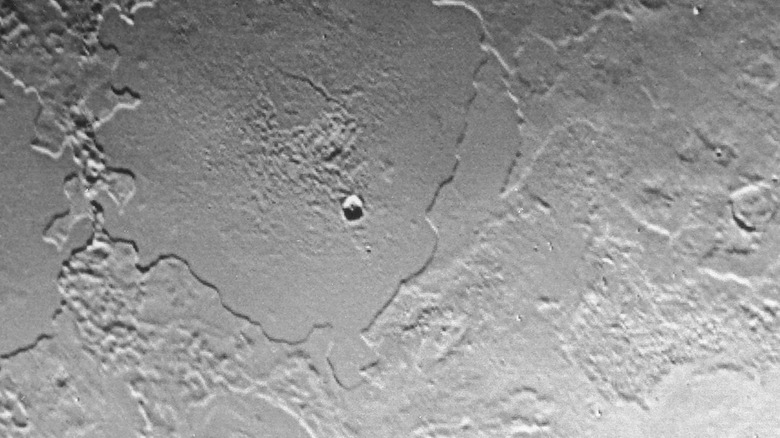

Triton's cantaloupe terrain is unique in the solar system

One feature of Triton's surface is seemingly unique, found nowhere else in the Solar System. Described by NASA, it's known as "cantaloupe" terrain, named for its resemblance to melon skin. This surface texture probably came about at some time in the past, when Triton's entire crust was melted and reshaped. The cantaloupe terrain consists of a series of irregular mounds, each a few hundred feet high and a few miles across, forming a surface covered with rolling hills. During some cataclysmic event in Triton's past, these hills were probably caused by huge globs of ice rising up through the moon's molten crust before they solidified in place. Among the cantaloupe hills, Triton's surface occasionally has large, flat areas, probably caused by lava from cryovolcanoes melting and then re-freezing the ice.

Being unique to Triton, the cantaloupe terrain is very interesting to planetary scientists. A presentation at the 24th Lunar and Planetary Science Conference examines it in detail, discussing how it shows folds and fault lines, likely caused as Triton cooled and its crust started to break and buckle under the stress. This strange landscape is often thought to have formed early in the moon's history. If true, this means that the most characteristic parts of Triton's surface are also the moon's oldest.

Triton is doomed

When Triton was captured into Neptune's orbit, chaos was unleashed, and some of it is still evident in the strange behavior of Neptune's moons. Space.com talks about the telltale signs of the havoc that Triton caused. As well as Triton is orbiting the wrong way, another of Neptune's moons, Nereid, hints at a violent past. Its orbit is wildly eccentric, hinting that the gravity of something else yanked it out of the more circular orbit it probably once had. That something else was probably Triton. While Triton may have survived the chaos which marked its arrival in Neptune's orbit, the event also sealed Triton's fate. Its days are now numbered.

Triton is already very close to Neptune. According to NASA data pages, Triton orbits Neptune more closely than the moon orbits Earth, and it's only going to keep getting closer. As an article in Time mentions, Triton is slowly sinking. It likely started out with a much higher orbit and has slowly been spiraling downwards towards Neptune ever since, as tidal effects produce a gravitational drag that pulls it in towards Neptune's upper atmosphere. This slow falling is known as orbital decay and, as a paper published in Astronomy & Astrophysics explains, it means that the future contains inescapable doom for Triton. In a few billion years, it'll eventually stray too close and be torn apart by Neptune's gravity. Shredded into fragments of rock and ice, leaving Neptune with a system of bright rings like Saturn.