12 Incredible Stories From The London Blitz

The Blitz was a period of near-constant bombing by the Luftwaffe between September 1940 and May 1941. It's unclear how many bombs were dropped, and how many civilians died. Historic UK puts the number at 43,500 casualties, while the Chelsea Pensioners say it was around 30,000. They add that 70,000 buildings were destroyed and 1.7 million were damaged. Then, Historic England says that in the years following the Blitz, England was hit by another series of air raids in what was called The Lull, or the Baby Blitz. Hundreds more died.

Survivors' stories are horrifying. A woman named Helen saw the horrors of war up close and personal when she was walking down Leadenhall Street. A bomb hit the building beside her, "... and a man, poor lad, was chucked out of a window and he fell on top of me. The Red Cross and the Salvation Army were working all about me, with the people who were dead and dreadfully injured. They took care of me." After getting cleaned up, she went back to her aunt's house, had tea, and went to a movie.

That's the Blitz spirit. Some survived, some thrived, and some took advantage, but no one was going to let Hitler win.

Defusing the London Palladium

When it comes to famous theaters, the London Palladium is definitely at the top of any list. Still, the only reason it's around today is because of the heroic actions of two men. The Royal Air Force Museum says that May 10-11, 1941, was the worst night of bombing throughout the Blitz. A whopping 571 sorties dropped 711 tons of bombs on the city, and it was one of those bombs that hit the Palladium.

Historic England says that the Royal Navy dispatched Sub Lieutenant Graham Maurice Wright and Able Seaman William Bevan, who got to the scene to find the mine lodged in the building's rafters. The only way for them to work on the bomb was for Wright to tie himself to a rafter while Bevan held his flashlight, and it was just after they fitted the bomb with a gag designed to delay detonation that it started ticking anyway. They freed themselves from the bindings that were holding them in place and got the heck out of there, but when the bomb didn't explode, they went back.

That was when it was time to disarm — Wright needed to lay on top of the bomb, while Bevan steadied him. It could have detonated at literally any second ... but didn't, and was successfully disarmed and removed. Both men were given commendations for their work, which included disposing of other bombs across the country (via The Comprehensive Guide to the Victoria & George Cross).

Sheltering in the Underground

Starting on the very first day of the Blitz — Sept. 7, 1940 — the people of London started heading down into the Underground stations to take shelter from the death and destruction on the surface. But they weren't supposed to. According to articles compiled by the British Newspaper Archive, the government issued stern warnings telling people they weren't supposed to stay in the stations for shelter, unless it was kind of a last-ditch effort to stay alive. No one listened, and instead, they'd just buy tickets and go in. Transport for London says it wasn't long before the government realized no one was going to be persuaded otherwise, so the London Passenger Transport Board stepped in.

Just three weeks later, there were about 120,000 people regularly sheltering there. Needless to say, it wasn't just cramped and unpleasant, but there were other problems, too. Especially? Illness and mosquitos. As the Blitz wore on, additions were made to the stations: First aid stations, more bathroom facilities, canteens and drink stations, and vending machines started popping up, along with around 24,000 bunk beds. Some trains were re-outfitted to act as traveling cafeterias, and by 1945, shelterers had consumed 545,454 gallons of tea.

Still, those sheltering there knew it wasn't guaranteed safety: When Trafalgar Station took a direct hit on Oct. 12, 1940, 7 people were killed. Another 19 died the next day, in Bounds Green, and on the 14th, 64 people were killed when Balham flooded.

Saving St. Paul's

St. Paul's was believed to be a major target, but it was also one of the buildings that Winston Churchill said had to be saved — if it were destroyed, British morale would have taken a devastating blow. So, the St. Paul's watch was reinstated. The group of volunteers had spent much of World War I putting out fires, and had patrols working 24/7 during the Blitz. On Dec. 29, 1940, 28 bombs hit — including, says Historic England, one that landed in the middle of the library. By then, they'd had some practice at bomb disposal.

A one-ton bomb landed in the middle of Dean's Yard on Sept. 12, and for that one, they called in the military. It was big enough that if it went off, it would have destroyed all of St. Paul's and a good amount of the surrounding areas, so it's safe to say that the three days it took to dig the bomb free of its crater had to be a nerve-wracking time. As if that wasn't nerves-of-steel enough, once the bomb was freed, it was loaded on the back of a truck. Lieutenant Robert Davies then hopped behind the wheel to drive it to the Hackney Marshes for detonation, and when they returned? The St. Paul's canon took everyone to the pub for pints.

Davies was awarded the George Cross, and after the war, the watch reorganized into the Friends of St. Paul's.

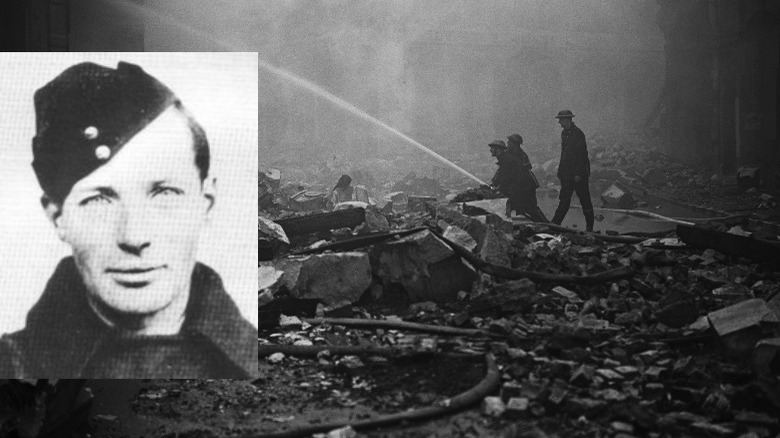

Canine heroes: The Magnificent Seven

The Daily Mail calls them the Magnificent Seven, and after the war, they were all awarded the Dickin Medal — the animal version of a military commendation for valor. It's still given out by the People's Dispensary for Sick Animals, and on the anniversary of the Blitz, they were remembered in a special roll of honor.

There was Beauty, a wire-haired terrier who helped the PDSA establish a special squad for rescuing animals from the rubble: She was never trained in search-and-rescue work, but still saved 63 of her fellow four-legged friends. Then, there's Irma, a search-and-rescue Alsatian who had an uncanny knack for finding people. On one occasion, she simply stopped at a collapsed home and refused to leave. Workers started to search in spite of the fact that there were no signs of life, and a day later, they rescued two girls from the ruins.

Jet, also an Alsatian, worked every night during the Blitz, and is credited with having the most successful rescue record of any of the nation's war dogs. The collie mix named Peter was signed over to the military by his owners, and went on to become a prolific search-and-rescue dog, just like Rip (pictured), a terrier who saved more than 100 people. Then, there's Thorn and Rex, Alsatians who were known for their almost supernatural ability to find people — even those trapped in burning buildings. They're not just good bois and girls, they're the best.

The man who saved Regent Street

There's no denying that most people would run away from bombs. Dr. Arthur Merriman did the opposite, and was ultimately awarded the George Cross for actions that saved London's Regent Street — and the lives of countless people. Merriman was a teacher pre-war, but joined up with the Department of Scientific Research when the battle came to Britain. It turned out that he had a knack for understanding — and diffusing — bombs and other explosive devices, so he was outfitted as an "air raid shelter inspector," then sent out to start defusing — especially when it came to bombs that no one had ever seen before

According to the Telegraph, the bomb that landed in the middle of Regent Street weighed around 550 pounds, and was big enough that had it gone off, it would have wiped out most of the West End. Merriman arrived on the scene and spent hours and hours draining the explosive material from the bomb, before refilling it with sandbags. A full 16 hours later, the bomb did go off, breaking a few shop windows.

Just a few months later, The London Gazette reported he had been awarded the George Cross. Merriman ended up going overseas to continue to consult on the construction of German bombs.

The serial killer who stalked the streets of the blackout

During the Blitz, British citizens were expected to do their part to make it more difficult for the Luftwaffe to navigate, and that meant observing strict laws regarding blackouts. No light was permitted to escape buildings, but unfortunately for several women, the darkness provided the perfect cover for a serial killer reminiscent of Jack the Ripper.

The first victim was a 40-year-old pharmacist named Evelyn Hamilton. Her body was discovered at an air raid shelter on Feb. 8, 1942, and although it was first believed to be a robbery gone bad, more bodies would start turning up. Evelyn Oatley was the next, tortured and mutilated before she was murdered. Then, Margaret Florence Lowe. And then? Doris Jouannet. But narrow escapes for Mary Haywood and Catherine Mulcahy resulted in invaluable clues. At each attack, the would-be killer left behind (respectively) a service respirator with a serial number, and a belt.

That respirator allowed law enforcement to track down an owner, and Gordon Cummins was arrested in connection with the Blackout Ripper murders. The killings had happened over a matter of days, reports Crime + Investigation, and the trial didn't last much longer than that. In spite of attempts to discredit law enforcement, fingerprint evidence also linked Cummins to the murders. He was found guilty, and hanged on June 25 of the same year.

Faith, the Church Cat

Sometimes, the most touching stories are the smallest ones, so let's take a little mind-cleansing break with a story told in "Famous Felines: Cats' Lives in Fact and Fiction." It started back in 1936, when a stray cat decided that she was going to call St. Augustine's & St. Faith's Church home, and no amount of times being put back on the street was going to change her mind. She was ultimately adopted by Father Henry Ross and named Faith, and quickly became a favorite face around the church. Fast forward to 1940, and Faith gave birth to a single kitten, named Panda for his distinctive coloring.

On Sept. 6, Faith demanded to be allowed into the basement. She checked it out, went up and got Panda, and carried him down. In spite of repeated attempts by the priest to get her to stay out of the basement, she insisted — and when he went to a meeting at Westminster three days later, she was still there.

The Blitz started the day after Faith and Panda headed into the basement, and when Father Ross finally made it back to his church, it had taken a direct hit. Walking through the ruins, he swore he could hear a faint cry. He did — he found Faith and Panda, alive and well, in the little sanctuary they'd sought.

From East London to the caves of Kent and an underground city

Kent's Chislehurst Caves are still open to the public, and it's safe to say there are few places that have that much history packed into 22 miles. They've been linked to the Romans and the Druids, and in the 1940s, they were home to an underground city populated by around 15,000 east Londoners hoping to wait out the Blitz.

It didn't start out as a fully-fledged city, says the Telegraph. At the time the war started, the tunnels were the property of a mushroom farmer who offered them to his neighbors as an emergency shelter. That grew and grew — a "Caves Committee" was created to manage things like sanitation and laundry facilities, while a system of public transport was arranged to get people to their day jobs and to school. Amenities grew, too, to include a church, movie theater, hospital, and barbershop.

The BBC interviewed one London resident who headed off to the caves with his family, after neighborhood homes were destroyed and several of his classmates were killed. He was 12 years old at the time, and recalled, "We had our own spot that we went to. ... There was a strange smell in there — it was the smell of the chalk, a kind of cold and dank smell. It was horrible. But you couldn't hear the bombs down there. ... We didn't feel scared, as down there, we felt safe."

Did Hitler spare his would-be headquarters?

Senate House is — as the name definitely doesn't suggest — the University of London's library, and it also houses their administrative offices. It's an undeniably awe-inspiring building, and as Historic England notes, it's a little ominous. That's partially because George Orwell used it for his terrifying Ministry of Truth in "Nineteen Eighty-Four," and it's also partially because of a rumor that Hitler had given the order not to bomb it, because he wanted it for Nazi headquarters.

The story goes that Hitler was making plans for what would happen when the Third Reich finally crushed London, and the invasion of the U.K. was complete. Supporting the theory is the fact that yes, the Nazis did have maps of London at the ready, but there's actually no concrete proof that this is anything but a myth.

Pretty compelling evidence that this was just a fanciful story is that the area was hit by more than 100 bombs, and five hit Senate House itself. One that hit on Nov. 7, 1940, was described in the journal of a visiting diplomat (via Londonist): "Splaaash! Craash! Tinkle! Tinkle! Oh I was no longer in my bed but on the floor. ... A bomb had hit us on the shoulder. It had broken through one floor and exploded on the floor below."

Black market blitz

Dr. Charles Berkoff has a slew of credentials, including serving on the board of the American Chemical Society. He also wrote a memoir about growing up during the Blitz, and shared a fascinating anecdote.

As a 6-year-old, his biggest concern about the war was if he would still get a chemistry set for his birthday. He had already figured out how to remove the charcoal from a gas mask and turn brown sugar into white sugar, and that, he wrote (via Historic UK), is about the time that a local limo driver asked him if he could remove the red dye from fuel. The red, he explained, was restricted use only, and getting caught with it meant strict fines. Still, he managed it: "I learned, much later, how he exploited my finding."

He certainly wasn't the only one. According to The Guardian, crime wasn't just rampant, it was creative. Rationing coupons became hot commodities and were sometimes stolen en masse, and perhaps predictably, looting was widespread. Others got more inventive, with some thieves opting to dress in Air Raid Precautions gear and help themselves to whatever they wanted. Ambulances became popular getaway vehicles, and when one vicar got suspicious about a volunteer, his investigation revealed that he was known for stealing valuables off the dead. Government aid was available to those who had lost their homes, and did people claim to have been made homeless multiple times? Absolutely — and one man got away with it 19 times before being arrested.

Barrage balloons were wildly successful ... sometimes, accidentally so

Look to the skies in photos of the Blitz, and many show massive balloons floating above city centers. Ballons might not be the first thing that comes to mind as a weapon, but according to the Maritime Archaeology Trust, they were used in both World Wars for offense and defense. The idea of using them as defense had a few different layers. For starters, the presence of the massive balloons made it harder for Luftwaffe pilots to navigate and target, and it wasn't easy to fly under them. They were tethered with heavy cables, and according to IEEE Power & Energy Magazine, the balloons brought down 102 planes just over London during the Blitz.

Then, an accident on Sept. 17, 1940, suggested there could be more to it. When a storm broke the tethers of some balloons and sent them floating over Denmark and Scandinavia, it wasn't long before those countries started reporting a loss of communications and electricity. The tethers started shorting out whatever they touched, drifting along like weird, man-made jellyfish.

The incident spawned Operation Outward, and the idea of using the balloons as an offensive weapon to take out German power and communications networks. Did it work? Some leaked reports suggest that it did some legit damage, but the program was discontinued in 1944.

From Highgate to high drama

Even amidst the devastation of war, life went on. Sometimes families immortalized the tough times in pretty unique ways: According to the BBC, one little girl born in the shelter of Chislehurst Caves was given the name Rose Cavena.

And, it turns out that another baby born in a Blitz shelter — this one in the Highgate tube station — went on to be rather famous. According to The Jewish Virtual Library, Margo and Richard Springer had fled ahead of Nazi persecution. The couple were Jews from Poland, and lost family members — his mother and great-uncle, as well as her mother — in the concentration camps. They escaped to England, though, and were living in London during the so-called Baby Blitz.

Margo gave birth on Feb. 13, 1944, while taking shelter in the Highgate tube station. They named their son Gerald Norman Springer, and when he was around five years old, they moved again — this time, to the U.S. and New York City. There, the boy would grow up to both run for political office and shorten his name a bit for his television career. And that name? Jerry Springer.