The Untold Truth Of Russian Alaska

Alaska is known as the 49th state and the Last Frontier, and like Hawaii, it is culturally quite distinct from the lower 48. Alaska's uniqueness comes in part from the century or so of Russian rule, which left an indelible mark on the culture, religion, and people of the state, blending Russian and Alaskan tradition in a way that extended to intermarriage and bilingualism among the progeny of colonists and their mixed-race descendants. Southern Alaska is dotted with Orthodox Churches that bear out this cultural unity.

Initially, the story of Russian Alaska is that of conflict and servitude between frontiersmen and natives. But this tale of violence became the story of a beautiful Russo-Alaskan symbiosis thanks to the Orthodox Church. This institution united Russians and different groups of Alaskans, allowing Russo-Alaskan culture to survive American encroachment into the present-day. Here is the untold truth of Russian Alaska, the forces that created it, and how the influences permeate Alaska today.

The Russians heard about Alaska from the Chukchi

As the Russian Empire drove East across Siberia and towards the Pacific Ocean, it encountered a group of tribes collectively known as the Chukchi, who today continue to live in the Russian Far East alongside the Bering Strait. Now, the Chukchi, per their own folktales, were familiar with the other side of the Bering Strait. Chukchi folktales, compiled in the Ancient Tales of Chukotka, share numerous motifs, symbols, and myths with Alaska natives. One story — the Tale about the Flying Shaman — includes a character that has travelled from Alaska, suggesting trans-Bering contacts between the Chukchi and other Siberian tribes in Asia and the native peoples of Alaska.

According to Polar Geography and Geology, Russian explorer Semen Dezhnev rounded the Chukotka Peninsula in 1648. At some point, he was told of the existence of two great islands to the west inhabited by "big-toothed people." One of these "islands" referred to the Alaska Peninsula (aka "the Great Land"), which includes the Aleutian islands. Equipped with this knowledge, Dezhnev's successors pushed further East towards America to learn more about this mysterious land and the resources that might lay there.

A Danish explorer was the first to make landfall

According to "Our Northern Domain," by 1711, Russian maps had begun depicting a land east of Siberia where the inhabitants had "tusks growing out of their cheeks and tails like dogs." Explorer Dmitri Gvozdev confirmed the existence of Alaska in 1731, and in 1740, the Great Northern Expedition under Danish commander and explorer Vitus Bering made the first European landfall in Alaska under the worst of conditions.

According to the National Park Service, the original scope of the Bering expedition was to find out if the Russian Far East was connected to America via a land bridge. After setting sail from Kamchatka with two ships, Bering's small party was separated during a storm that blew his ship towards a mysterious island against the magnificent backdrop of snow-capped mountains. He had landed on Alaska's Kayak Island.

On Kayak, Bering's party found a series of abandoned huts, suggesting the presence of human habitation in the surrounding region. So his party explored the length of what today are the Aleutian Islands, where they encountered the Aleuts. After a gift exchange, Bering's party turned back to Kamchatka, spending a miserable winter on Bering Island being tormented by the local arctic foxes that stole their food and belongings (via PBS). The crew survived on sea otters and sea cows and managed to return to Kamchatka. Bering, however, did not live to report his discovery. He died on December 8, 1741, along with half of his crew.

Fur was as good as gold

Following the Second Kamchatka Expedition's Alaska landing in 1741, Russia began to gradually settle Alaska beginning with the Aleutian Islands. According to the Library of Congress, the first to make the jump were Siberian serfs called promyshlenniki. These men operated as independent traders and trappers, sometimes by coercing Aleuts and other natives to trap for them and then selling their furs at profit.

The fur trade operated much like the later gold rushes of American history. Per the Sitka History Museum, one Russian trapper named Emilian Basov went to Alaska and returned to Kamchatka with a load of otter pelts, which he sold at an enormous profit. The subsequent "fur rush" brought a wave of promyshlenniki to Alaska. Some stayed behind, taking local Aleut trapping and business partners. But, the disorganized nature of the trade led the Russian government to bring some order through the creation of a colonial company.

In 1799, the Russian-American Company, a joint-stock company resulting from a merger of several smaller trading enterprises, received a monopoly on the Alaskan and North Pacific fur trade. It subsumed the promyshlenniki class, which became its employees, and a booming organized Alaskan fur trade was born. The Chinese elite became the principal and most lucrative market for Alaskan fur. But the profits soon attracted attention from American, British, and French trappers, who saw thinly-settled Russian America as an enticing business and colonial opportunity.

The Convention of 1824 solved territorial issues over fur trade

According to Smithsonian Magazine, Russian America never had more than 800 permanent settlers at one time — and that was at the colony's peak. But Russia still hoped to hold on to Alaska and expand its influence along the Pacific Northwest Coast. Meanwhile, American and European settlers and explorers were moving northwest, too.

To solve territorial disputes and ensure that they did not spill into conflict, Russia offered the United States a deal in 1824. The Russo-American Convention between Alexander I (above) and James Monroe was an agreement that mutually recognized American and Russian navigation rights along the Northwest Coast and Alaska while forbidding them to do any business with each others' settlements without the express permission of the local governor. The boundary between the two spheres was set at the 54th parallel, which both states agreed to respect.

The most important aspect of the convention for Russian Alaska, however, concerned trade with natives. The treaty's fourth and fifth articles allowed American ships to engage in trade with natives both along the coast and in the interior, goods such as firearms, spirits, and other war munitions excepted. While these articles were meant to resolve tensions and prevent conflict, it also undercut the Russian-American Company's authority in the Pacific Northwest and Alaska. Per the Pacific Historical Review, Russia had effectively surrendered its Alaskan monopoly by allowing foreign merchants into its lands, eventually leading to the territory's sale to the United States.

Relations with the natives were not the best – at first

Russian colonists and frontiersmen encountered new groups of people native to Alaska, from Aleuts to Tlingits. But these rough-and-tumble frontiersmen were not particularly well-disposed to the native population. According to the 1910 Alaskan survey "Our Northern Domain," Russian traders frequently enslaved natives and killed those that refused to cooperate with them, leading to a cycle of massacres and counter-massacres. To add to the hardships of first contact, native Alaskans had no immunity to Old World diseases such as smallpox, which devastated the native communities, taking the lives of over half the population in some villages. Smallpox vaccination through a system of Russian hospitals slowed the devastation, but many natives refused it out of distrust and fell victim to the disease. And for some others, it was already too late. Facing depopulation, the Russian colonial authorities relocated surviving natives to larger villages for concentrating manpower.

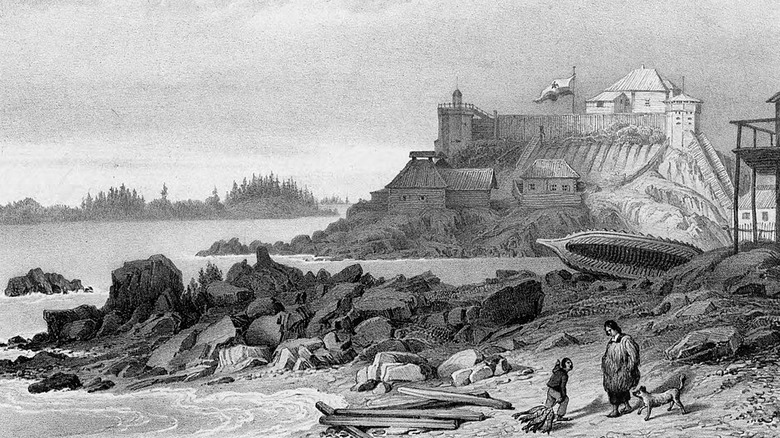

In response, at least one tribe — the Tlingit — fought back. Per the National Park Service, the Tlingit elected a warlord named K'alyaan to lead a united Tlingit resistance around Sitka, then the Russian settlement of Novo Arkhangelsk. The Tlingit captured the town, fortified their positions and defeated a Russian counterattack at the 1804 Battle of Sitka. The conflict ended with an 1822 settlement that allowed the Tlingits to rebuild their settlements next to Russian Sitka, but relations between the two sides remained tense until Russia left Alaska in 1867.

The Orthodox Church rectified the problems

Per "Our Northern Domain," the tsarist government under Catherine II was appalled at the rough treatment of the natives and ordered the promyshlenniki to treat the natives as "their new brethren." Instead, according to St. Herman of Alaska Orthodox Church, the Russian-American Company, instead requested eight monks to evangelize the natives into subservience in 1794. But as noted in a KUAC Fairbanks interview, the monks had other ideas. They had come to win souls, not to serve RAC policy.

Before setting out, the monks were told to behave themselves as guests in a foreign land home. In practice, they were to respect Alaska natives and their cultures while evangelizing — not eradicate them. The result was a harmonization native languages and cultures — particularly Aleut — with Orthodoxy. The monks also defended the natives against Company abuses, slavery, and indentured servitude and Aleut repaid them with their trust and souls.

Apart from the faith, the Orthodox Church's most important contribution to the Aleuts (and eventually other natives) was an alphabet to write their languages so they could learn prayers, catechesis, and create their own works. St Innocent of Alaska, one Russian Alaska's most prolific writers, learned Aleut and subsequently wrote the "Indication of the Pathway to Heaven" and a Catechism used for educating converts. In addition, he translated the Gospel of Matthew among a number of other readings, sermons, and prayers. The mission capped its achievements with an Aleut translation of the Orthodox Divine Liturgy, evidence of the ROC's commitment to its new flock.

Alaska gave Orthodoxy a number of saints

Alaska has produced a number of Orthodox saints, most famously its patron St. Herman, "Wonderworker of all America." According to the St. Herman of Alaska Orthodox Church, Herman was among the eight missionaries sent to Kodiak to evangelize the locals, embracing conversion over coercion despite colonial authorities' misgivings. But it worked, netting nearly 7,000 Aleut conversions within the first year of his mission.

According to the Orthodox Church in America, Herman became a respected figure among the Aleuts, who flocked to him to hear his sermons — presumably delivered in their own language. But his principal focus was on Aleut children — the ROC's future in Alaska. For them, he founded a bilingual school and an orphanage, and even baked cookies for them out of kindness and affection for his pupils. Inspired by his faith, the Aleuts became ardent defenders of Orthodoxy — even to the grave.

St. Herman had a young Aleut disciple named Peter, who in 1812, traveled with a Russian expedition to California. There, Spanish authorities captured and tortured them to renounce Orthodoxy for Catholicism. Peter refused and died a martyr. Upon hearing of his pupil's death, St. Herman crossed himself and invoked Peter to pray for him and all sinners. The martyred youth eventually became St. Peter the Aleut (above).

Alaska developed its own Russian dialects

Aleut children educated in church schools often emerged bilingual in Aleut and Russian. The phenomenon then expanded as bilingual families developed through increasingly common Russo-Alaskan intermarriages, whose creole children were also often bilingual but retained the customs of their Russian fathers, too (via Ethnohistory). The linguistic interchange and borrowing birthed new Russian dialects that became the lingua francas of Alaskan creoles and assimilated Orthodox Christian natives.

The principal varieties that survived are Ninilchik Russian, named after the eponymous village on the Kenai Peninsula and a Kodiak dialect. According to linguist Evgeny Golovko, Kodiak villagers identified themselves as Siberian-descended, Russian Orthodox Alaskans who prided themselves on their Russian-Aleut bilingualism, suggesting the dialect's origins among mixed families. However, none of the interviewees could read Cyrillic, and many had forgotten the dialect through attrition or had never learned it. Linguist Wayne Leman, who grew up in a Ninilchik Russian home, noted that his own dialect — although still alive — suffered after its speakers came under American pressure and discrimination for speaking it. Thus, then language stopped being passed on.

The two dialects are differentiated from standard Russian in pronunciation, grammar, and vocabulary. Ninilchik Russian for instance, only has a masculine gender, using the feminine exclusively for biologically-feminine nouns. Kodiak Russian pronounces "v" as "w," while Ninilchik Russian replaces the throaty Russian vowel "Ы" with a plain "i," as seen in this language sample.

Russia sold it to the United States in goodwill

By the 1850s, the Western Historical Quarterly notes that the Russian-American Company had a manpower shortage. The fur trade was no longer profitable as otter populations were depleted. No one wanted to move to Alaska anymore, and the colony became a financial drain. The geopolitical situation in 1860 did not favor Russia, either. Per the University of Hawaii, Russia suffered a humiliating defeat against a rival Franco-British coalition in the Crimean War, and Britain even had a plan to partition Russia (via Russian Review). Meanwhile, the British also were looking to partition Russia's only major friend and ally — the United States — by recognizing the Confederacy.

Per the Library of Congress, the British had designs on Alaska too. So Tsar Alexander II decided to sell it to the United States and leave it in friendly hands. An 1859 Russian offer was postponed as the Buchanan and Lincoln administrations grappled with secession and the Civil War. But after the war, Russo-American relations were at a high point following cooperation during the American Civil War, and so negotiations went forward. Russia initially asked for $5 million. However, upon seeing Andrew Johnson's Secretary of State William Seward's (above) enthusiasm for purchasing Alaska, the parties agreed upon $7.2 million, a bargain price of 2 cents per acre. Russia pulled out of the Last Frontier, leaving its subjects to navigate their new American sovereigns alone.

The sale inspired some to move closer to Russia

The sale of Alaska was not received enthusiastically among the partly-Russified Alaska natives and the Alaskan creole class. While the latter group, per the Treaty of Purchase, were given U.S. citizenship, the former were not, falling into the category of "uncivilized tribes." Once gold was discovered in Alaska in 1896 (via Library of Congress), American prospectors rushed to the territory leaving former Russian subjects outnumbered in their own lands.

For the natives, the Alaska Purchase brought nothing but problems. Russia's old Tlingit enemies in particular clashed with American settlers and missionaries attempting to convert them to Protestantism. Now, according to the University of Alaska — Fairbanks, the Tlingit, despite their problems with Russia, had never faced attempts to eradicate their culture. American missionaries on the other hand, banned Tlingit language and culture in their schools in an effort to "kill the Indian ... save the man." In comparison, the Russian Orthodox Church had preserved Alaskan culture and language.

In response, the Tlingit rallied around the Russian Orthodox Church, which they turned into their own institution. As noted in Olga Tsapina's review of Professor Sergei Kan's "Memory Eternal," the Tlingit combined native traditions, Russian spirituality, and the Tlingit language into their own Orthodox niche. Even with the material benefits of assimilation, the Tlingit chose Orthodoxy for its compatibility with their native spirituality and worship styles. The result was a collection of Tlingit hymns, prayers, and Russo-Tlingit religious brotherhoods to reinforce Tlingit Orthodoxy among men.

Today, Russian Orthodoxy predominates among natives in the old colonies

Due to the Russian Orthodox outreach among the Alaskan native peoples during the colonial era and the early days of American rule, many Alaska natives adhere to Russian Orthodoxy today — even when they have little to no Russian ancestry themselves.

A 2006 LA Times article interviewed the Orthodox faithful of the Aleutian Islands. Although the Russian language has long since disappeared, the churches remain along with Alaska's only Orthodox Seminary — the St. Herman Seminary of Kodiak Island. As reported today, Alaska natives are likely the future of the Russian Orthodox Church in Alaska, comprising four-fifths of all seminarians. According to Smithsonian Magazine, in the rural areas of Southern Alaska and the Aleutian Islands, the local Orthodox Church is the only religious establishment in town — the legacy of missionaries and intermarriage between Russian frontiersmen and Alaskan women.

Unfortunately, as younger people have left their villages, some rural churches, especially on the Aleutian Islands, have faced disrepair and lack funds. But their faithful have refused to give up on their churches, noting the Orthodox Church and Our Lady of Sitka supported them through the more brutal periods of their history and present, preserving their traditional cultures and creating unique Russo-native syntheses that distinguish the natives of Southern Alaska from those that avoided Russian rule.

The most recent Russian settlement occurred in 1968

Although Alaska's surviving Russian influence is mostly spiritual and onomastic, one modern Russian stronghold post-dating the colonial era survives. According to the Library of Congress, a group called Old Believers separated from the Orthodox Church in 1666 after then-Patriarch Nikon made a series of corrections to the liturgy and changed some other traditions — including how the Sign of the Cross was made. Objectors were told to fall in line or be persecuted, and the Old Believers chose the latter. The Old Believers fled to Siberia and other fringe areas of the Russian Empire, where they lived until Communist persecution forced them to flee again.

According to the Atlantic, one group eventually established the village of Nikolaevsk in 1968 after a sojourn in Brazil. This village, located on the Kenai Peninsula, is almost like a time capsule, comparable to Amish or Mennonite towns. As seen on this Voice of America segment, women wear head coverings and long skirts, men don beards, and Russian has traditionally been the lingua franca. In some stricter Old Believer villages outside Nikolaevsk, outsiders are not permitted to enter for fear that they will corrupt the lifestyle.

Despite attempts to shut out the world, Nikolaevsk's main priest Fr. Nikolai Yakunin has noted the community has increasingly shifted to English. Many of Nikolaevsk's youth operate principally in English rather than Russian, and many children don't speak it at all. Thus, it seems that Nikolaevsk's Old Believers have become more open to the world — even if reluctantly.