Ann Eliza: The Ex-Wife Of Brigham Young Who Fought Against Polygamy

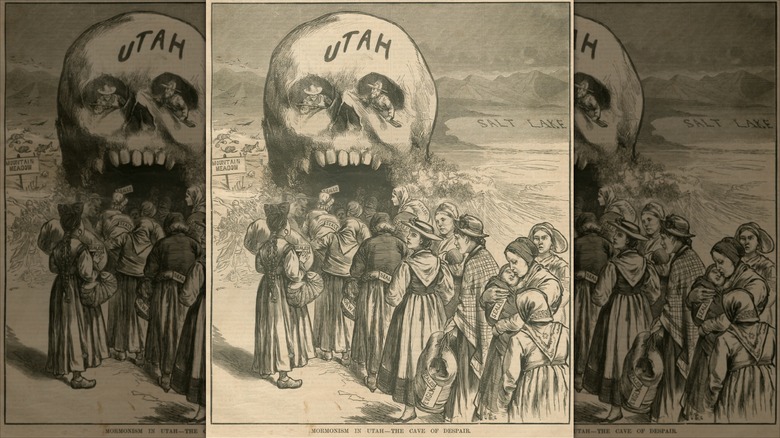

Polygamy was a serious issue for the early members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, often known more succinctly as the Mormons. Though it was once enthusiastically embraced by early Mormon leaders, the practice was kept quiet for decades, long after prophet Joseph Smith proposed it in the 1830s, per the official site of the church. When the church publicly acknowledged this in 1852, according to The New York Review, it caused an uproar amongst non-Mormon "Gentiles." Many deemed the practice "barbarous."

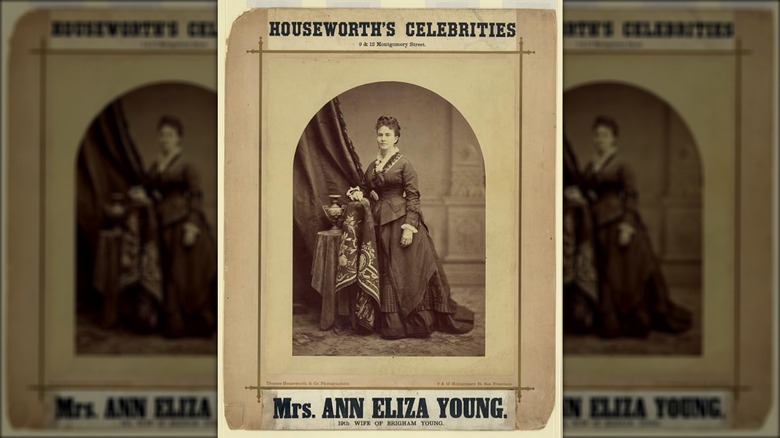

Of those figures who arose to speak against polygamy, few would have been more notorious to Mormons than Ann Eliza Young. Her work didn't sting just because she had been born into the faith and was an early migrant to the Mormon stronghold of Utah. It must have been all the more humiliating and hurtful because she was a former wife of church president Brigham Young.

With the publication of her memoir "Wife No. 19" in 1876, the already disenchanted Ann Eliza purported to tell the real story of her life as one of the wives of Brigham Young (despite the title, it's not clear exactly where she landed numerically in the lineup of Young's spouses). But did she tell the whole truth about her life? How did polygamy become part of the church? And did Ann Eliza Young have a hand in its demise? Here's the story of how one of Brigham Young's ex-wives fought against polygamy in the early Mormon church.

Ann Eliza Young came from an LDS family

According to Ann Eliza Young's account in "Wife No. 19," she was born into a devout Mormon family in 1844, in the Mormon stronghold of Nauvoo, Illinois (via NPR). She noted that her father, Chauncey G. Webb, and mother, Eliza Churchill, were some of the earliest converts to the new and growing religion. She recalled that her mother was a true believer, with a "dreamy, devoted, and mystical" outlook that nevertheless drew in Ann Eliza's more skeptical father to the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (via "Wife No. 19").

Though her mother reportedly found great comfort in her faith, Ann Eliza claimed that the practice of polygamy "cursed her life, as it has that of every Mormon woman." Yet, for Ann Eliza, the youngest child of five and the family's only surviving daughter, it would have been all that she had known. Chauncey took a second wife by the time Ann Eliza was just a year old, reportedly commanded to do so by none other than prophet Joseph Smith himself (via "Wife No. 19"). Mother Eliza acquiesced, though Ann Eliza wrote that she had a "horror" of Smith's revelation of polygamy.

Like so many of the other faithful early Mormons, moving from place to place was also a requirement. Per Encyclopedia.com, the Webb family moved first from Illinois to Missouri, and then on to Utah in 1846. Ann Eliza would have been about 2 years old at the time.

Her first marriage was difficult

According to HistoryNet, Ann Eliza's first marriage to fellow Mormon James Dee was nothing short of a disaster. The two seemed constantly at loggerheads, arguing over matters like whether or not more wives should join the family (Ann Eliza was apparently against the idea). They had two sons together, but that did not stop Dee from abusing his wife. That was one of the incidents that led to the breakup of their marriage. Though Mormon unions are typically sealed "for all eternity," as prophet and church leader Brigham Young would have proclaimed at their wedding, that sealing was canceled in 1865.

That left Ann Eliza free to marry again, though she initially claimed that she was not interested in another round of marriage. But then there was Brigham Young. Per HistoryNet, he told the young woman that she was "very pretty" and "very much improved" after her split from Dee. Perhaps his marriage proposal was further sweetened by the offer of housing and an allowance of $1,000 per year, which likely became all the more interesting when her family encountered financial troubles.

So, two years after Brigham Young first began expressing interest, the marriage-cautious and polygamy-skeptical Ann Eliza joined the prophet's group of wives. Though Brigham's family would later claim that the troublesome Ann Eliza was the one leading him on, the fact remains that they agreed to wed and were sealed on April 7, 1868. She was 23, while he was 66.

Brigham Young was a big name amongst Mormons

Brigham Young wasn't just any Mormon pioneer. Instead, he was no less than the church's president and prophet. However, when he joined the religion in the 1830s, he was a near-destitute widower with two children (via PBS). Eventually, he became a faithful disciple, though he initially reacted to the revelation of polygamy with disgust, saying that he would rather die than take on more than one spouse at a time. Of course, as Ann Eliza or any one of Brigham's more than 50 wives would have told you, he eventually came to accept the practice with some enthusiasm.

After Joseph Smith's 1844 death at the hands of an angry mob, the forceful and energetic Brigham Young stepped into his place as the church's president and prophet with a direct line to the Lord. Per PBS, it was Young who led the Mormons to Utah, where he established a compound in Salt Lake City that included the Beehive House (his main residence) and the Lion House (meant to house many of his wives). From then until his death in 1877, Young proved to be a charismatic but also contentious leader. He often came into conflict with the United States government, to the point where President James Buchanan declared that the Mormons were a threat in 1857. He pardoned them the following year, but not before soldiers were mobilized and a group of non-Mormon travelers was killed by members of the religion in the Mountain Meadows Massacre.

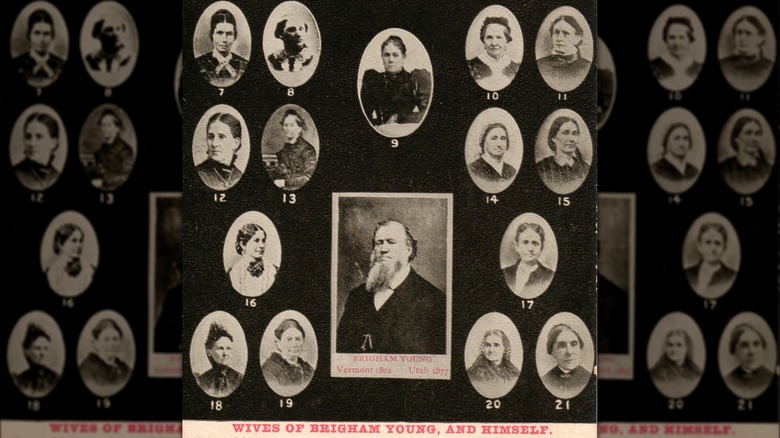

Ann Eliza was one of many wives

Though he was initially reluctant to engage in polygamy, Brigham Young eventually took to the practice in force, marrying over 50 wives and fathering more than 50 children amongst them (via Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought). By the time Ann Eliza came to maturity, it was an established practice for many Mormons, though one that was often kept secret for fear of drawing the ire of outsiders.

According to PBS, Joseph Smith first presented the doctrine of polygamy in 1843, though he may have reportedly received that revelation in 1831 and married his first plural wife only a few years later. However, if you asked anyone about it prior to 1852, they would have denied that such a thing happened amongst church members — though it definitely did occur. It proved to be a controversial practice from the start, causing some of the faithful to break away early on, including Smith's widow, Emma.

In Salt Lake City, however, it was obvious the church's president was living with many wives. His residences, which included the Beehive House and Lion House (via Utah History Encyclopedia), were right in the center of the city. The former served as Brigham Young's primary home, while the latter housed 12 of his wives and their children. As History notes, polygamy wasn't for everyone, however. In practice, it was reserved for the powerful spiritual elite, such as Brigham and other church leaders.

Some allege that Ann Eliza Young was a jealous wife

Quite a few of the more than 50 spouses in Ann Eliza's new household were apparently Brigham Young's wives in name only, according to Dialogue. "Some of those sealed to me are old ladies whom I regard rather as mothers than wives," he told editor and politician Horace Greeley in 1859 (via Utah History To Go). Records indicate that, amongst his many wives, only about 16 actually gave birth to his children.

That isn't to say jealousy and competition in the Young households did not exist. Ann Eliza noted that Brigham and one of his wives, Amelia Folsom Young, got along especially well, to the point where they sat together at one table while the rest of the family dined at another. According to The Salt Lake Tribune (via Utah History To Go), it was clear to Ann Eliza that Amelia was chief amongst Brigham's wives. She sat next to him at the theater in a separate box, received plenty of gifts, and was in charge of her own residence, the Gardo House — which, of course, was often graced by the presence of their mutual husband.

Certainly, in "Wife No. 19," Ann Eliza does not use kind language about Amelia, instead recalling that she was rather frosty and unafraid to wield her power. The Salt Lake Tribune implied that Ann Eliza was jealous of Amelia's position, wanting the delicacies and perhaps the affection reserved for a wife in the inner circle.

Ann Eliza left her marriage in 1873

Though quite a few wives of Brigham Young lived in the Beehive House, the sheer number of them meant that a significant portion of spouses lived in their own quasi-independent households. There was the Gardo House, which was so thoroughly affiliated with Brigham's favorite wife in its early days that the residence was popularly known as "Amelia's Palace" (via Utah History To Go).

Ann Eliza also had her own separate household, though it was apparently a busy one. According to "The Twenty-Seventh Wife," she had taken in a series of boarders to help make ends meet, a business decision that was supported by her second husband. Yet, that seems to have led to the end of their marriage. Two Gentile friends, the Methodist Reverend C.C. Stratton and his wife, were introduced to Ann Eliza by one of her houseguests. Already growing discontented with her religion and lot in life, Ann Eliza found that her conversations with Stratton gave her the push needed to leave both her husband and her religion (via "The Twenty-Seventh Wife").

This would not prove to be an easy move, however. When Ann Eliza left Brigham Young in 1873, her divorce petition included some strong claims. Per the Chicago Daily Tribune, she argued that Brigham had been cruel and neglectful, and that he had considerably more money than he claimed. Rather unsurprisingly, Ann Eliza Young was officially excommunicated from the LDS church on October 10, 1874 (via Dialogue).

She went through a legal battle with Brigham Young

Though she was kicked out of the LDS church in October 1874, Ann Eliza Young's business with her former faith and its adherents was far from over. First, there was the matter of her divorce, which was forced to go through the courts before it could be finalized. According to the journal Dialogue, the divorce was granted in January 1875. Brigham Young was also pinned with a monthly alimony payment of $500, as well as a then-whopping $3,000 in court fees. He initially refused any such payments, a move that landed him in jail for a day and an extra $25 in fines. Eventually, the alimony matter was set to rest, given that the nature of polygamous marriage within Mormonism made the legality of Ann Eliza and Brigham's union a tricky gray area.

That question of whether or not Brigham's various marriages really counted in a legal sense put him in a vulnerable position. As Dialogue notes, he stood to be prosecuted for unlawful cohabitation, a big issue in the wider world of non-Mormon gentiles. It didn't help that Mormons, for all their work to set up a quasi-independent state in the territory of Utah, hadn't bothered to define marriage in a legal sense for plural wives. The dropping of the alimony issue in Ann Eliza's divorce may have held off the question for the time being, but it would only kick the can down the road for a bit longer.

Ann Eliza Young was part of a larger anti-polygamy movement

With its claim to show the true inner workings of one of the biggest and most famous polygamous households of all, "Wife No. 19" was nothing short of a bombshell. Brigham Young clearly wasn't free of his ex-wife just yet.

Ann Eliza Young was not acting in a vacuum, however. Polygamy was utterly shocking to many non-Mormons and, as such, there was a growing anti-polygamy movement in the United States and its territories. Activist Kate Field made bank on her "Mormon Monster" lecture series, delivered in the decade after Ann Eliza's 1876 memoir. According to The Journal of American History, Field even wrote that Mormon women agitating for the right to plural marriage were engaging in a "monstrous" practice that was nothing more than "self-degradation."

Other reactions to the practice ranged from bawdy jokes to cultural panic. As The New York Review reports, after the church publicly fessed up to its revelation of polygamy in 1852, politicians and other public moralizers went so far as to call it barbarous and on par with no less a sin than slavery. Women, they said, were being bound up in a system that counted them only as chattel and not human beings. For crusaders such as Kate Field and Ann Eliza Young, this was the time to free those women, expose evil, and perhaps make a name for themselves in the process.

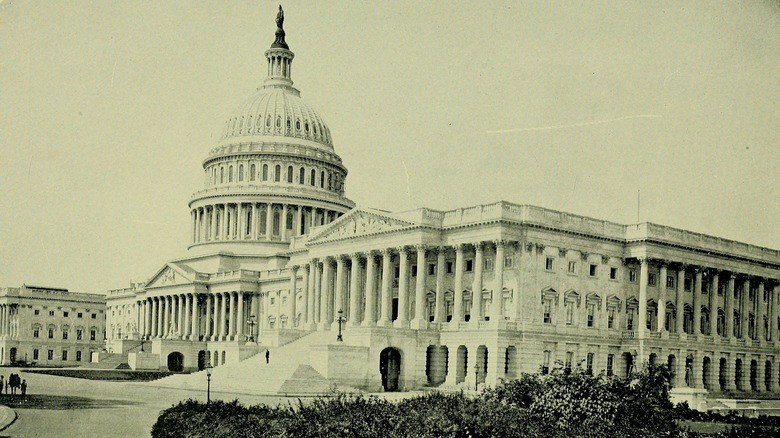

The U.S. government eventually banned plural marriage

Spurred on by growing awareness of and opposition to polygamy, the federal government of the United States began to take notice. Some legislative action had already been taken prior to the publication of Ann Eliza Young's memoir, such as the Morrill Anti-bigamy Act of 1862. According to the First Amendment Encyclopedia, it was also known as the somewhat more obvious Morrill Act for the Suppression of Polygamy, having been passed in direct response to the polygamy practiced by Mormons in the Utah territory. Besides putting serious punishments in place for polygamists, the act also nullified the LDS church's incorporation and limited its landholdings. Yet, though some prosecutions did stem from this act, it was difficult to enforce.

The pressure didn't really increase until 1882, with the passage of the far more powerful Edmunds-Tucker Act. This allowed for the government to repossess even more of the church's property and other wealth, despite challenges from Mormons both in the media and the Supreme Court. Per PBS, other Mormons refused to testify regarding the practice and even evaded authorities while defending polygamy, despite increasingly tense debates on the subject. What's more, the church had lost one of its most prominent and staunch defenders of polygamy when Brigham Young died in 1877. At the time, many questioned if the faith could really continue without its "Lion of the Lord," as Brigham came to be known (via TIME).

The LDS church abandoned polygamy next

Facing considerable pressure from the government and the public, the LDS church finally buckled. On September 24, 1890, church leaders issued the "Mormon Manifesto" that directed all the faithful to renounce polygamy. Another directive, issued by church leaders in 1904, threatened polygamists with excommunication (via PBS). As The First Amendment Encyclopedia notes, a significant portion of the church's confiscated property was returned by the U.S. government shortly after the manifesto was released.

This change arguably helped the LDS church survive in a world staunchly against polygamy. Not all Mormons were ready to give up the now-entrenched practice, however. Indeed, according to the Utah History Encyclopedia (via Utah History To Go), some dug in their heels and committed themselves and their families to the practice. A few enclaves continued the practice, believing that government pressure did not mean that the faithful should go against God's word. These include the modern-day Fundamentalist Church of Latter-day Saints, many members of which live on the Utah-Arizona border to this day (via Southern Poverty Law Center).

Even in mainstream Mormonism, hints of polygamy remain. As the BBC reports, LDS men can still be "sealed" to multiple women in the afterlife (though women can still only have one husband, even when they've left their earthly existence).

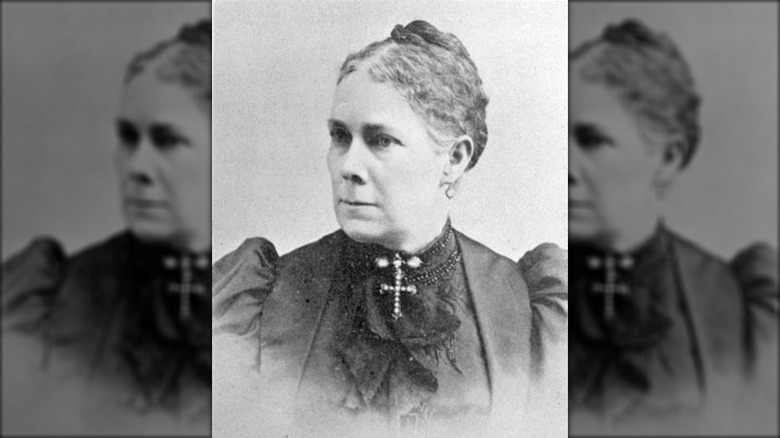

Ann Eliza Young had a complicated life after her marriage

After her excommunication, Ann Eliza Young joined the Methodist Episcopal Church, per "The Twenty-Seventh Wife," and continued speaking against Mormonism and polygamy, including giving interviews to members of the press (via the St. Louis Globe-Democrat).

Towards the end of her life, it seems clear that Ann Eliza had a strained relationship with her family. According to Encyclopedia.com, she married Moses Denning in 1883, but the union apparently fell apart after he cheated on her. She published a revised edition of "Wife No. 19" in 1908 (which conveniently skipped over her divorce and third marriage), but her trail faded significantly after that.

Ann Eliza's connections to her children and grandchildren may have been tenuous as well. As her oldest grandson reportedly said after nearly crossing paths with her in New York City when she would have been about 86, "I hope to hell I never see her again" (via "The Twenty-Seventh Wife"). Whether or not said anecdote really happened (and it may not have, given the confusion over dates and ages), we can be certain that the family legend that she died alone and is buried in obscurity (via Encyclopedia.com) isn't quite right. Instead, according to a death certificate shared at Find a Grave, Ann Eliza died in Sparks, Nevada, on December 7, 1917.