The Truth About The Prince Once Recruited To Be America's King

Every year, Americans come together to celebrate Independence Day on July 4 in commemoration of the adoption of the Declaration of Independence by the Second Continental Congress in 1776, per the Library of Congress. But not as many people think about the state of the union 10 years later when the United States of America faced big trouble, according to Mental Floss.

Nathaniel Gorham was the president of the Continental Congress, and in the months leading up to the Constitutional Convention, he became increasingly concerned about the nation's future. The American Revolution was a long and expensive war, which left the United States of America in debt so deep it sparked a monetary crisis. Realizing the republic's fragility, Gorham entertained the unthinkable: a return to a monarchy.

But he went much farther than simply thinking about it. After consulting with the Prussian military leader General Friedrich Wilhelm von Steuben, who helped train the American military during the War for Independence, he sent an invitation to a foreign prince to become America's king. Here's the incredible story of the moment the USA nearly gave up the republic for a return to a constitutional monarchy.

A monetary crisis rocked America

In the three years following the American Revolution, the fledgling republic faced an existential crisis, according to Mental Floss. Gripped by debt incurred during the war, veterans of war, merchants who sold their goods on credit, and countries that supported the United States remained unpaid. What's more, very little currency circulated, exacerbating the problem. But collecting on this debt proved tricky. After all, taxes remained a sore point within the newborn states.

Another issue that raised many emotions was that of federal versus state control. Under the Articles of Confederation, the states were loosely tied together as a republic. But the system proved broken even before it was implemented, leaving some wondering about whether a republic was the best form of government for the former colonies.

It was a perfect storm that imperiled the future of the nation. As the monetary crisis continued to heat up, violent fractures appeared in the confederacy of states. Adding to this were what John Adams referred to as "many and powerful enemies" of the young republic (via "A Study of 'Monarchical' Tendencies in the United States: From 1776 to 1801"). Some of these enemies were internal, making the situation incredibly tenuous.

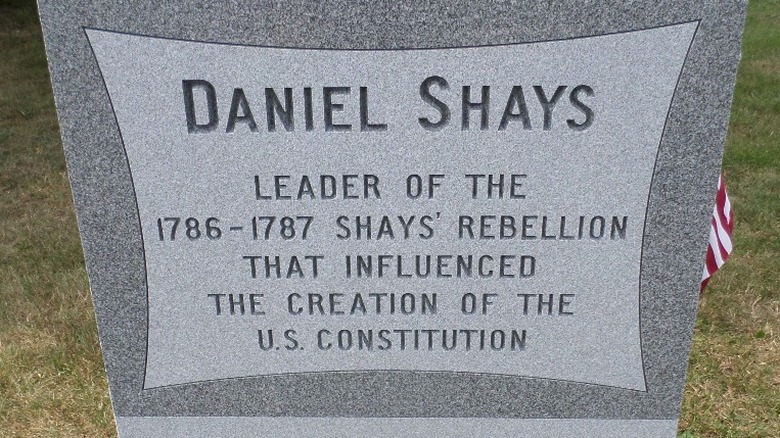

Shays' Rebellion underscored the problem

Shays' Rebellion epitomized the financial desperation the nation faced and was led by Revolutionary War veterans, per Britannica. Up through 1783, America had prospered, but everything changed rapidly as a financial depression settled in. Money had to come from somewhere and how the government collected it triggered the uprising. Men like Daniel Shays stood to lose possessions as a result of high taxes and overdue debt (via History).

Underscoring the irony of the situation was Shays' model reputation as a Revolutionary War hero, having taken up the call to arms in April 1775 at Lexington. By December 1775, he worked as a second lieutenant in a Massachusetts-based regiment, and by January 1777, he headed up the 5th Massachusetts Regiment. From Bunker Hill to Ticonderoga, he put it all on the line to fight against the British. After retiring from the army in 1780, he held a handful of public offices.

As the United States descended into economic chaos, property owners suffered. Men like Shays faced huge losses and even time spent in debtor's prison. In the face of such tyranny, Shays and his so-called rebels came together to fight back between 1786 and 1787. They confronted the Massachusetts militia in front of the Springfield Armory, per The Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History. In the aftermath, Shays and 12 other men received the death penalty from the Massachusetts Supreme Court. Shays petitioned for a pardon in 1788, which he soon received.

Fears about the nation falling into anarchy and confusion

Shays' Rebellion exposed the vulnerability of the government and the likelihood it might fracture under the weight of financial pressures (via Mental Floss). It also gave Americans a taste of mob rule, a fire that nobody wanted to play with, according to The Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History.

George Washington reflected on Shays' Rebellion in a letter to Henry Knox on February 3, 1787, sharing his shock over the situation. He wrote, "If three years ago any person had told me that at this day, I should see such a formidable rebellion against the laws and constitutions of our own making as now appears I should have thought him a bedlamite — a fit subject for a mad house" (via the National Archives). Moving past his surprise over the rebellion, the future first president of the United States noted that the government must be capable of enforcing its own laws or face unmitigated chaos and anarchy.

Washington articulated the anxiety and fear that so many in the country felt. But he also expressed cynicism and apathy, explaining he didn't want to attend the upcoming Philadelphia Convention because he saw it as a pointless exercise. Without a change in course, Washington speculated the nation would fall into total confusion and lawlessness. And his fears were based in reality as the French Revolution and the Reign of Terror proved, beginning just two years later.

The Articles of Confederation proved inadequate

At the heart of the problem was the Articles of Confederation, America's first attempt at an organizing governmental document, according to Mental Floss. Chief among the Articles of Confederation's issues was its lack of executive teeth. Designed by an incredibly weak Continental Congress, the document proved just as dysfunctional, with no practical means of enforcement, as reported by TIME. And everybody knew it.

But what proved far more challenging was how to fix it. After all, the governance of a nation as a republic was an ancient concept that had been visited with little success throughout history, from the short-lived direct democracy of Athens to the medieval republic of Florence. Knowledge of the tumultuous history of these human experiments in governance didn't provide a clear way forward. The unprecedented nature of the United States' attempt at self-governance earned it the nickname the "American Experiment" (via The Heritage Foundation).

These examples even made some of the United States' leaders question whether the country should be a republic, fearing mob rule. Although such an opinion was hardly popular in the wake of the American War of Independence, some of the Founding Fathers secretly considered other administrative structures, including an enlightened despot.

Tempted by enlightened despotism

In the 18th century, enlightened despotism proved all the rage, as modeled by the so-called "Greats": Frederick II, Peter I, and Catherine II (via Britannica). These authoritarian leaders, inspired by the principles of the Enlightenment, were thought to rule fairly, emphasizing religious toleration, administrative reform, and economic development. And to varying degrees, this proved true.

According to History, Frederick the Great famously banned torture and argued for a national criminal code after coming to office. He also consolidated Prussia economically and reworked Berlin as a cultural and scientific capital. To top this off, he offered public education to students throughout Prussia, per the Daily Republic. Through such reforms, he came to personify the type of despotic ruler that some members of the Enlightenment considered ideal.

Frederick the Great's brother, Prince Henry of Prussia, had also drunk deeply from the wellspring of Enlightenment thought. The Prussians shared these philosophical and intellectual leanings with the Founding Fathers. So, it's no wonder that some within the Continental Congress — fearing a total fracturing of the nation — might turn to a man like Henry. In times of great uncertainty and unrest, the heavy hand of a dictator can feel reassuring, but the concept couldn't have proven more anti-American.

They called it the Prussian Scheme

In the years following Yorktown and the defeat of the Redcoats, chaos characterized the nation, according to TIME. In response, exploring means of governance (apart from a republic) proved tempting to a small but mighty class of U.S. landowners, per "A Study of 'Monarchical' Tendencies in the United States: From 1776 1801."

This included men like Nathan Gorham, the president of the Continental Congress. By 1786, he spearheaded an effort to revert to a constitutional monarchy, as told in "The Life and Correspondence of Rufus King: 1816-1827." As the tale goes, he invited a foreign-born monarch to step in and bail the United States out, in an event that would come to be known as the Prussian scheme (via The American Historical Review).

Gorham wrote to the leader with the pedigree to be an enlightened despot, Henry of Prussia. Like his brother, Henry of Prussia had been trained from the cradle up to be a leader. At the age of 14, he became a colonel in the military, and he enjoyed a profound appreciation of the Enlightenment like his brother and the Founding Fathers. To men like Gorham, who feared the Great American experiment looked more like a slow-motion train wreck, Henry appeared cut from the ideal cloth to rule over the struggling, new nation.

General Friedrich von Steuben was the messenger

Rumors of the Prussian scheme plagued the United States for years, and some believe it provided the impetus for the natural-born-citizen clause for presidents in the Constitution. But the plot remained unconfirmed until 1824 when New York Sen. Rufus King wrote about it, per Mental Floss. According to King's account, the Prussian scheme was abandoned because the Founding Fathers decided the public would never support it.

Nevertheless, stories of the Prussian scheme persisted for decades, and King's account fanned their dying embers. What's more, a biography of General von Steuben by Friedrich Kapp confirmed the claim and pointed to the general as the messenger who reached out to Prince Henry, according to Richard Krauel, writing for The American Historical Review.

Interestingly, Kapp communicates the fact that von Steuben didn't like the idea, either. He reportedly told American leaders after they proposed it, "As far as I know the prince he would never think of crossing the ocean to be your master. I wrote him a good while ago what kind of fellows you are; he would not have the patience to stay three days among you." Von Steuben had extended knowledge of Americans as a volunteer at Valley Forge, and he also had served under Henry, making him the most well-suited to deliver such a message.

Americans felt warm and fuzzy about the Prussians

If the thought of a Prussian prince ruling America sounds outlandish, a little context shows it wasn't nearly as far-fetched to some in the wake of the Revolutionary War, as reported by TIME. Many Americans had warm feelings for the Prussians because of the help the colonial army received from General Friedrich von Steuben, starting at Valley Forge.

Three years into the war, the colonies had reached a low point, according to Smithsonian Magazine. The army had just endured a brutal winter at Valley Forge where everything was lacking, from clothes to shoes and food. Baron von Steuben arrived on the scene at the perfect moment, bringing renewed discipline and morale to the forces. One teenage soldier described the intimidating Prussian, "He seemed to me the perfect personification of Mars. The trappings of his horse, the enormous holsters of his pistols, his large size, and his strikingly martial aspect, all seemed to favor the idea."

During his time as a volunteer with the Continental Army, von Steuben transformed a failing band of well-intentioned but underprepared brothers into a professional fighting machine. As a veteran of Prince Henry's army, the esteem and admiration of von Steuben could easily be transferred to his former boss, Prince Henry. If the Americans had willingly accepted a Prussian baron as their god of war, perhaps they'd prove as accommodating to a Prussian prince.

Prince Henry of Prussia's response found

Although Baron Friedrich von Steuben remained skeptical the Prussian scheme stood a chance, it appears that he did send a formal invitation along to Henry of Prussia in Berlin, according to "The Life and Correspondence of Rufus King: 1816-1827." Although this document has been lost to time, anecdotal evidence supports its one-time existence, per TIME.

Namely, Rufus King claimed Henry of Prussia rejected the appointment, replying to Gorham's request by arguing, "The Americans had shown so much determination [against] their old King, that they [would] not readily submit to a new one." Yet, despite such claims, many considered the Prussian scheme horrible hearsay with no basis in reality. But then material evidence emerged in the early 20th century (via Mental Floss).

The evidence came in the form of a letter from Henry of Prussia to Baron Friedrich von Steuben. The language of the missive is veiled in secrecy and even includes mention of code, representing a noteworthy level of confidentiality. Although the response remains vague on Henry's part, it represents the best proof available that the Prussian scheme actually existed.

George Washington saved the day

Although Prince Henry of Prussia didn't want to touch America with a 10-foot pole, that didn't stop some Founding Fathers from advocating for a radically different type of government, per TIME. Alexander Hamilton was so enamored by a strong ruler that some think he took part in the Prussian Scheme (via Mental Floss). After Henry of Prussia proved unwilling, Hamilton continued to advocate for a strong ruler.

After George Washington became president, Hamilton advocated for the position to be lifelong. John Adams wanted the president addressed as "His Majesty." Both of these suggestions might have resulted in a wildly different leadership role, and here's where we owe George Washington a huge debt of gratitude. Not only did he refuse to be called "His Majesty," but he also rejected the idea of the presidency as a non-ending position. He set the standard for no more than two terms by refusing to run a third time.

George Washington wasn't interested in the role of an enlightened despot, and he wasn't about to take advantage of the nation during its most vulnerable time. Having fought with the people he now represented, he knew firsthand the great cost they paid to throw off the yoke of monarchy. And he wasn't about to subject Americans to it once more. After Washington retired, King George III of Great Britain declared him "the greatest man in the world." Unlike Henry of Prussia, Washington was the man the United States of America really needed.

The stability crisis birthed the United States Constitution

Once Prince Henry of Prussia turned down the offer to relocate to the United States, the Founding Fathers found other means of stabilizing the country, according to TIME. Delegates gathered in Philadelphia to craft the Constitution, engineering the blueprint for the great American Experiment.

In crafting the U.S. Constitution, the Founding Fathers had to take much into account, including human nature, per The Heritage Foundation. They crafted the nation's charter, remembering the lessons learned from the Articles of Confederation. George Washington concluded, "We have probably had too good an opinion of human nature in forming our confederation." Unlike the Articles of Confederation, the United States Constitution did a better job of walking the fine line between self-interest and the principles that would help the republic run properly, like consensus and compromise.

Of course, navigating this line meant finding a way to avoid the concentration of power among too few individuals. As a result, the Founders worked hard to disperse and divide up governmental powers, embedding "checks and balances" between the three branches of the federal government, as well as a limitation of power at the federal and local levels. The concept is known as federalism and represented the best way to maintain people's personal and domestic interests. And, most importantly, Americans found it far more agreeable than inviting a foreign prince to take the reins.