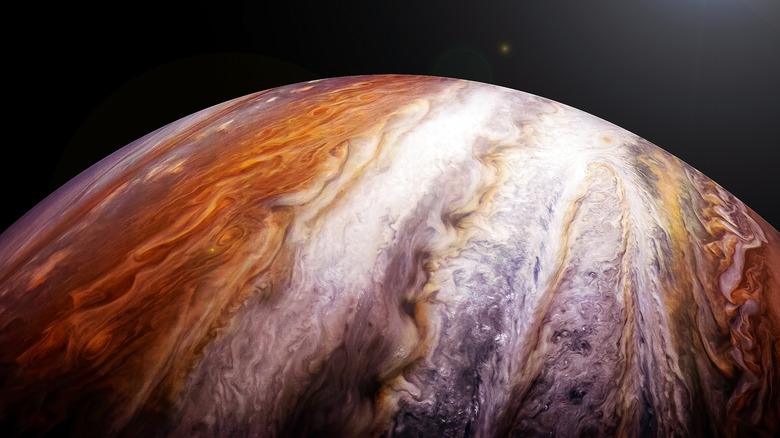

Does Jupiter Actually Eat Smaller Planets?

The Roman god Jupiter was almost eaten by his father. According to myth, Jupiter's father, Saturn, feared his children would rise against him. To defend himself, he decided his best option was to eat them, one by one. He devoured every single one except Jupiter, who was hidden from Saturn by his wife, Ops. The way she decided to trick him? By giving him a stone to eat instead (via The Collector).

Now, in a strange twist of fate, it appears that the planet Jupiter, which was named after the Roman god, is something of a voracious eater itself. According to new research, while it was forming into a massive gas giant, Jupiter may have "eaten" planetesimals (via Live Science). These rocky baby planets would have given Jupiter the bulk it needed to form a large, dense core, and eventually grow into the largest planet in the solar system.

What can we say? Like father, like son.

The formation of planets

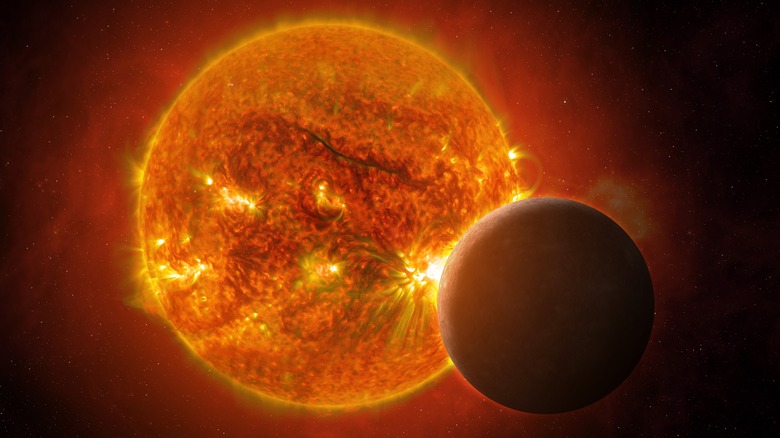

But, how can a planet eat another planet? It comes down to the process of planet formation. When a new star is created, significant amounts of space dust swirl around in its general vicinity, according to NASA. Pulled in by the gravity of the growing star, this dust can sometimes collide with and adhere to other fragments, leading to the slow clumping of larger and larger rocky bodies in space. Over time, some of these fragments can get big enough to form planetesimals, and eventually, they may even form full planets.

It's important to keep in mind that the process of planet formation can vary depending on which type of planet is being generated. The Earth, for instance, is considered a rocky planet, since the majority of the Earth is made up of rocky, solid elements, with a relatively dense atmosphere to cap it off (via Sciencing). On the other hand, there are some planets, called gas giants, which are predominantly composed of gasses. These planets, which include Jupiter among their ranks, tend to be larger than rocky planets and are also found further out in the solar system, where colder temperatures allow gas to cling to gaseous planets, according to NASA.

Scientists discover Jupiter's past

The new revelations about Jupiter's past came after NASA's Juno telescope was able to get a look under Jupiter's clouds in 2016, according to the Economic Times. The probe showed a surprisingly high density of heavy metals in Jupiter's core — as much as 9% of the planet's overall mass, according to Live Science. To scientists, this signaled that Jupiter was likely formed from the accumulation of planetesimals, as opposed to the collision of smaller rocky bodies, since only planetesimals would have been large enough to create such a dense core.

The study doesn't indicate that this process is ongoing — Jupiter isn't still "eating" other planets. Still, the new research has lots of interesting implications for the understanding of our solar system, giving scientists reason to second-guess their ideas about the planetary formation of planets like Saturn, according to Global News. And, there's plenty of other cool research going on with Jupiter, including an ongoing study into whether one of Jupiter's 79 moons may host life (via NASA) and new monitoring of the planet by the James Webb Space Telescope, Global News notes.