The Civil War's Most Notorious Female Spies

When the Civil War broke out in 1861, it was the culmination of longtime tensions between the northern and southern states in eastern America. History explains that slavery, the rights of states, and even the ongoing westward expansion topped the list of reasons why the Civil War began, especially after President Abraham Lincoln was elected in 1860. The war was naturally accompanied by hundreds of spies who worked for both the Union and the Confederacy. Historynet rightfully points out that these secret agents of sorts were important to both the Union and the Confederacy — and a good number of them were women.

During the Victorian era (via Legends of America), women were relegated to maintaining their homes and farms as their men went to war. Soon, however, the ladies were pushed into service as nurses and suppliers of food and medical aid. But that wasn't enough for certain women, who decided to join the war effort as spies. Author Karen Abbott tells of married couples joining forces to spy during the war, including one couple on their honeymoon. Other spies could be as young as the 12-year-old who posed as a drummer boy. Other women, like one that the Nashville Union newspaper reported on in 1861, operated alone.

But were these ladies really "spies," or just champions for a cause? Read on and decide.

Fannie Battle

Mary Francis "Fannie" Battle was born in Davidson County, Tennessee, according to the Tennessee Encyclopedia. Her father, a wealthy plantation owner, sent her to the Nashville Female Academy, but she was back home when the Civil War broke out. Two of her brothers died at Shiloh and her father was held prisoner by the Confederates. Fannie and her sister-in-law decided to become spies for the Confederacy. Their job was to woo Union soldiers for information and report back to the Confederates. In 1863, however, Fannie was caught smuggling important papers, arrested, and eventually transferred to jail in Washington, D.C.

After the war, Fannie taught school in Nashville for several years. In 1891, according to the Fannie Battle Day Home for Children, she saw a crowd gathered around a malnourished little boy who had been hit by a wagon. Fannie discovered that the boy and five siblings, as well as their mother, had been abandoned by the father of the family and were struggling to survive. Fannie rented a room near the mother's job in a cotton mill and created Nashville's first daycare for children.

Fannie died in 1924. Today, the day home does not allude to Fannie's illustrious past. Travel writer Tabitha Hawk photographed Fannie's 1924 tombstone, which was erected by Fannie's friends and salutes her "43 years devoted to unselfish work."

Belle Boyd

Belle likely wouldn't have become a spy, but when a Union soldier walked into the family home, yanked a Confederate flag from the window, and insulted her mother (per History), the enraged teen shot him to death. Eastern Illinois University's Historia magazine editor Rachael Sapp confirms that a Union general judged Belle was "perfectly right" in her actions. But Belle was far from finished with the Union. Instead, she became what Legends of America calls "the most infamous spy of the Civil War."

Throughout the war, says War History Online, Belle used her girlish charms to gain information from Union soldiers and pass it on to Confederate troops. She crept through Union camps at night, snatching up stray firearms laying on the ground and hiding them for her allies to find (per Clara Barton Museum). She listened through a hole in the door of a hotel as Union officers discussed their plans, and dodged bullets to bring that information to Confederate General Thomas "Stonewall" Jackson. Belle was arrested twice, but married Union officer Samuel Harginge after he helped her escape to London. When the war was over, Belle wrote her memoirs in 1865 and died in 1900.

Pauline Cushman

Actress Pauline Cushman was working in New Orleans when she married her husband, Charles Dickinson, according to Ohio State University. After the Civil War began and Dickinson died, Pauline was performing in Kentucky during 1863 when two Confederate soldiers offered her $300 to toast the Confederacy onstage. Battlefields says Pauline, a budding Union spy, checked with Union Colonel Hurley Moore about the matter, who encouraged her to accept the soldiers' offer. She was immediately fired from the performance, but was quickly offered an official job spying for the Union. Pauline accepted.

Pauline was sent to Nashville, where she carried out her duties. Eventually, however, she was arrested and incarcerated (via Smithsonian Magazine). Pauline was nearly hanged, but was reportedly saved by Union forces. Alternatively, the National Park Service says Pauline faked being sick to avoid her fate. Either way, she was released after the war and went on to perform for P.T. Barnum.

Sadly, Pauline was impoverished and addicted to morphine when the San Francisco Morning Call reported her death in December of 1893. The plan was to bury her with the military honors she so deserved. Today, Findagrave confirms she is buried in San Francisco National Cemetery.

Nancy Hart Douglas

1911's The Photographic History of the Civil War states that Nancy was so good as a Confederate spy, the North offered a sizeable award for her capture. Nathan Mote of The Heritage Post writes that after her brother was killed by the Union, Nancy was at a family party in 1861 when she saw some Union soldiers marching past. The girl shouted, "Hurray for Jeff Davis!" She was fired at four times, but escaped injury. Next, she worked briefly with a guerilla group, the Moccasin Rangers, before officially joining Confederate forces, writes Debra Basham of the West Virginia Encyclopedia.

Shortly after joining the Confederates, Nancy was captured by the Union, but was able to negotiate her own release and immediately shared what she knew with the Confederates. In 1862, Nancy was disguised as an elderly woman when Union troops commandeered some food from her cabin. But one member of the party, Colonel Starr, recognized her, and she was again arrested. At Summersvillle, Nancy and others were prisoner in a vacant building, but she managed to grab the gun of one soldier and killed him, escaping on Starr's horse (per Dee Butler at the West Virginia State Dept. of Education). After the war, Nancy married. She died in 1902. Findagrave features a picture of her tombstone, which reads "Civil War Heroine."

Zora Fair

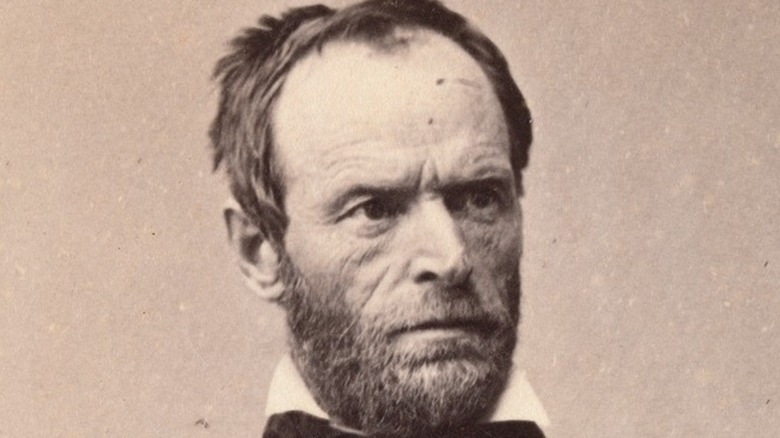

Only tidbits are available to tell Zora's story. The first real mention of her story was in Jeffersonian Magazine in 1908, which describes the beautiful young woman's decision to use walnut stain to make herself look like one of the Black servants in her household at Oxford, Georgia. Her disguise allowed her to infiltrate Union General William Tecumseh Sherman's (pictured) headquarters in 1864, although her strange skin color was much discussed. "A Standard History of Georgia and Georgians" explains that Zora successfully returned to Oxford, but the letter she wrote to Confederate General Joseph Johnson, which explained what she knew, was intercepted by the Union.

Before long, Sherman tracked Zora to Oxford, where his men knocked on doors looking for her. Sherman promised that "I don't mean to hurt her, but will give her a scare," according to the Wall Street Journal. But the City of Oxford Self-Guided Tour says Zora was able to hide in the attic of a house to avoid detection. Alternatively, the Historic Marker Database cites the original historical marker claiming the girl was fired upon, taken in for questioning, and released.

Zora died soon after the war ended. The house where hid in Oxford, at 1005 Asbury Street, still stands.

Antonia Ford

Antonia came from a wealthy Virginia family, and Historynet confirms she earned her literature degree at Buckingham Female Collegiate Institute. But the girl would soon use her talents in a way nobody expected.

According to Smithsonian Magazine, Antonia shared intel she learned from Union soldiers with Confederate General J.E.B. Stuart. In 1861, Stuart commissioned her as his aide-de-camp, telling others that Antonia was to "be obeyed, respected and admired." Once, Confederates searching her home commanded the lady to stand up. "I thought not even a Yankee would expect a Southern woman to rise for him," replied Antonia (per Clara Barton Museum). The embarrassed soldiers left, and never discovered the important papers Antonia hid in her dress.

In 1863, according to HistoryNet, Antonia next provided enough information to Captain John Mosby for him to conquer Fairfax and take 33 prisoners that included Brigadier General Edwin H. Stoughton. This time, another spy was sent to Antonia's house and lured the girl into showing her Stuart's letter, says the Washington Post. Antonia was subsequently arrested. During her time in prison, says Encyclopedia Virginia, she fell in love with Union major Joseph C. Willard. Antonia gave up spying, pledged her love to the man, and eventually married him. They had three children.

Lottie and Virginia Moon

Virginia (pictured) was just an Ohio schoolgirl at the beginning of the Civil War, per the Tennessee Encyclopedia. She was expelled, explains author Larry Eggleston, after she shot down an American flag and scratched "God Bless Jefferson Davis" on the window of a store. Back home, she would use disguises to carry important papers to Confederate troops between Memphis and Cincinnati, and traveled as far as Canada. The Confederate Philatelist writes that Virginia's sister, Charlotte, also was a spy who once was at the altar with a Union soldier. When she was asked to take him as her husband, however, she answered "No siree, Bob!" and ran.

Additionally, Charlotte once managed to get aboard a carriage with President Abraham Lincoln and overhear war plans, which she passed on to the Confederates. As for Virginia, she was captured towards the end of the war, despite pulling a gun on the Union soldiers arresting her. She did manage to pull the message she had hidden in her blouse, "and in three lumps swallowed it." Upon her release, she eventually moved to New York City. During the 1920s, she appeared in two films, "Robin Hood" and "The Spanish Dancer" (via the Internet Movie Database). She died in 1925 (per Findagrave). Today, according to the Oxford Observer, Charlotte Moon's house still stands in Oxford, Ohio.

Rose O'Neal Greenhow

Even as a Maryland teenager, writes Rachael Sapp, Rose maintained friendships with important politicians in Washington, D.C. Unfortunately, she lost her husband and five of her children during the 1850s. Despite having three more children to raise, Rose decided to support the Confederacy by becoming a spy, according to History. The lady was quite clever at her work. She flirted with Union men to gain information, used her fan to send codes to Confederate soldiers, sewed important documents into her clothes, and even carried messages in her hair, per the Clara Barton Museum.

Even after she was caught, Rose managed to keep on spying. It was Allen Pinkerton himself who finally gathered enough evidence to arrest Rose (via Smithsonian Magazine). The Washington Post reports that she was held at the Old Capitol Prison with her 8-year-old daughter, who continued passing on information via her candy wrappers. After her release, Rose went to Europe and was paid $2,000 in gold for writing her memoirs. Unfortunately, says War History Online, Rose's boat was rammed by a Union gunboat. The lady drowned, the gold pieces sewn into her dress pulling her underwater.

Emeline Piggot

Born in North Carolina to a large family, Emeline was alarmed at the hardships suffered by some Confederate soldiers camped across the road from the family home. According to NCPedia, the girl joined the Confederacy, and boldly refused to attend Union affairs that her Confederate boyfriend could not attend, until he was killed in 1861. After that, writes Carolina Coastline's Mike Wagoner, Emeline began hosting parties for Union soldiers, but also smuggling clothing, medicine, and top secret papers in her hoop skirt. Her brother-in-law assisted her, and if they were detained, Emeline would flirt with the Union troops until they were allowed to pass.

At home, says the North Carolina Department of Natural and Cultural Resources, Emeline was able to distract soldiers so her brother could get food to the Confederates. She was detected, imprisoned, and taken to court numerous times, but escaped a trial each time. While in jail, she also evaded an attempt to kill her. After her release, she continued her underground missions for the Confederacy and supported the southern cause right up until she died in 1919.

Today, the Jones House in Craven County, where Emeline was imprisoned, remains standing and is maintained by Tryon Palace.

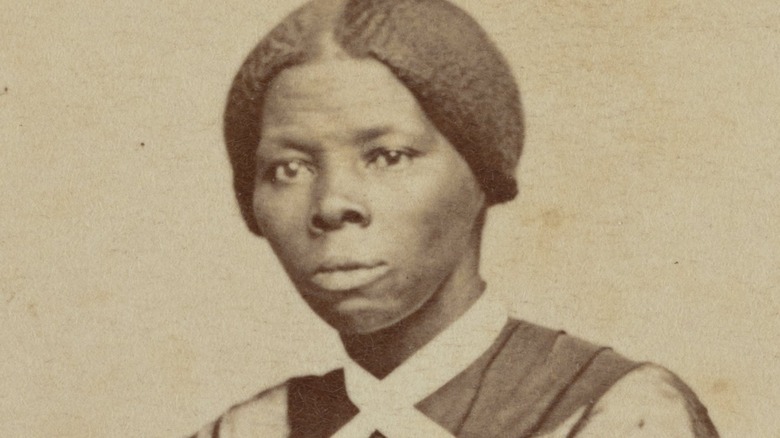

Harriet Tubman

Born in 1820, the amazing Harriet had already escaped from slavery in 1849, and worked on the Underground Railroad to free others (per History). During the Civil War, she worked as a Union cook and nurse until she was recruited as a spy in 1863 (per Smithsonian Magazine).

Maneuvering upriver with several hundred Black soldiers, Harriet made history when she was able to destroy Confederate supplies and free over 750 enslaved people. By then, the Underground Railroad had ended, but Harriet continued helping to rescue emancipated slaves. Following the war, Harriet moved to New York and used her home to house elderly and sick people, according to Harriet Tubman Byway. Yet the government refused to pay her a pension until 1899.

She was buried with honors after her death in 1913. Harriet is remembered in many ways today. Her home is now on the National Register of Historic Places, according to the National Park Service, and is now a National Historic Park. In 2003, Congress paid the rest of her pension, which was given to the Harriet Tubman Home. And in 2016, plans were made to put Harriet's face on the $20 bill, but that has yet to happen.

Elizabeth Van Lew

Raised in the south, Elizabeth became anti-slavery, and talked her brother into freeing the family slaves in the 1840s (via History). During the Civil War, she and her mother would visit Union soldiers incarcerated at Richmond, Virginia's "brutal" prison. The Clara Barton Museum states that Elizabeth and her mother began by bringing the men needed food and supplies, but eventually smuggled books with needles as well. The prisoners could use the needles to poke holes into certain letters in the books as a way to send messages.

In 1863, Union General Benjamin Butler offered Elizabeth a job as a spy. As an official spy, Elizabeth enlisted her servants' help to send secret messages in hollowed out eggs and vegetables. Rachael Sapp writes that with her manner of raggedy dress, she was able to smuggle soldiers from jail to safety. Legends of America verifies she also flew the Union flag at her home, as a way of making her Confederate neighbors think she was crazy. They called her "Crazy Bet."

War History Online reveals that Elizabeth spent her $10,000 inheritance to purchase enslaved people, who then went free. Following the war, President Ulysses S. Grant gave her a job as Postmaster General of Richmond.

Mary Elizabeth Bowser

Elizabeth Van Lew's unlikely partner was her former slave, Mary Elizabeth Bowser, whom she helped free around 1851 (via Ohio State University). Like many of the Van Lew slaves, Mary stayed on and worked for the Van Lews. But Encyclopedia Virginia verifies that much of Mary's life is shrouded in mystery due to a lack of reliable resources. Even Smithsonian Magazine can only guess that her real name was Mary Jane Richards when she married a free Black man, Wilson Bowser, in 1861.

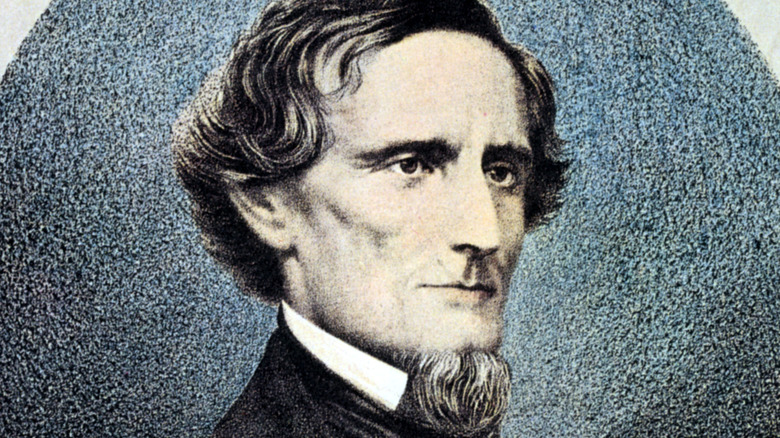

Thanks to Elizabeth, Mary received an education and willingly joined in on the Union cause. In 1865, Elizabeth was able to get her former slave a job in the house of the "Confederate White House" of Jefferson Davis (pictured), where he and his cabinet members openly discussed strategies in front of her. The African American Registry says Mary conveyed what she heard to President Ulysses S. Grant, and that she nursed and housed Union soldiers — but also that she, not Elizabeth, was the one they called "Crazy Bet."

Afterthe war, Mary spent time giving talks about her spy work. In 1867, she founded a freedmen's school in Georgia and was headed to join her husband in the West Indies, but History verifies that nobody knows what really became of her.

Dr. Mary Edwards Walker

Born in New York, Mary commonly wore men's clothing while helping out on the family farm, according to the American Battlefield Trust. As a teen, she attended several schools and, per the U.S. Army, earned her medical degree from Syracuse Medical College in 1855. During her marriage shortly afterwards, Mary wore trousers, refused to say "obey" in her vows, and kept her last name. And when she volunteered as a Union Army surgeon in 1861, she wasn't allowed to become one due to her sex. Mary volunteered instead.

Mary worked in Virginia during 1862 (per Changing the Face of Medicine). The following year, she worked in Tennessee, then Ohio, and finally, Georgia, where she finally received a paid surgeon contract. American Civil War says she was considered a spy since she crossed enemy lines to treat Confederate soldiers. She was arrested as such in 1864, spending four months in prison under unsanitary and grueling conditions before being traded for imprisoned Confederate doctors.

A year later, she became the first woman to receive the Congressional Medal of Honor for her work. She also tried unsuccessfully to vote, and was arrested for cross-dressing in 1871. When her medal was revoked in 1917, Mary refused to give it up until she died in 1919. In 1977, her family successfully appealed to President Jimmy Carter to restore the honor.