The World's Oldest Living Things

In 1875, France was in the early years of its Third Republic, and the world-famous Eiffel Tower had not yet been built (via Britannica). It was in this newly industrialized world, shortly before the inception of the Art Nouveau movement, that a woman named Jeanne Calment was born in Arles, a city in Southern France. During her life, Calment would go on to see the world change drastically, with the widespread adoption of electricity, the appearance and eventual dominance of motorcars in cities, the invention of the microwave oven, humans setting foot on the moon, the digital revolution, and even the earliest Nokia cell phones. As the book Validation of Exceptional Longevity cataloged, by the time of her death in 1997, Calment was 122 years old, making her the oldest recorded human ever to have lived.

Jeanne Calment was not only the oldest human, however. As Discover Wildlife has noted, humans are the longest-lived land mammal in the world, and Calment was older than any other. While the global average human life expectancy is around 70-80 years, a study in Nature Communications suggests that the maximum human lifespan may be between 120 and 150 years — a respectable number of years. But human lifespans are far from the world's longest. There are many things living on Earth that live on timescales we humans can barely comprehend, and some of them challenge our ideas of what an individual living thing is or even what it means to be alive.

Giant Tortoise – 190 years

The world's most long-lived land animals are tortoises, living a famously slow and sedentary existence. As of 2022, the oldest tortoise ever recorded with a confirmed age is named Jonathan. As Smithsonian Magazine explains, he's currently 190 years old and still enjoying good health. A Seychelles Giant Tortoise native to the Seychelles archipelago in East Africa, he currently lives on the island of St. Helena in the South Atlantic ocean. While Jonathan is the oldest with actual recorded age, however, he's very likely not the oldest ever. One challenger was an Aldabra Tortoise named Adwaita, who lived in Kolkata, India. As the BBC reports, Adwaita passed away in 2006, but his age was uncertain. He's said to have been at least 150 years old, but there's some evidence he may have been as much as 250 years old.

The fact that giant tortoises have such long lifespans is interesting to zoologists, and studies have been performed to investigate why they live so much longer than other land-dwelling creatures. One study, reported by Yale News, analyzed the DNA of giant tortoises from the Galapagos, who can easily live for over a century. It turns out they have gene variants not found in shorter-lived creatures, including adaptions to suppress cancer, boost immunity, and repair DNA. In other words, giant tortoises are naturally evolved to remain healthy into their old age.

Bowhead Whale – 211 years

The oldest mammal ever recorded, as Alaska Science Forum explains, was a Bowhead whale. Living in the frigid Arctic waters, bowheads are specially adapted to the cold, with blubber a foot thick to protect them from the icy cold and thick bony skulls to help them break through ice sheets. These whales can grow to 60 feet (18 meters) long, and they already weigh a ton on the day they're born. The indigenous Inupiaq and Yupik people have traditionally hunted whales for over a millennium, and it's not uncommon for them to recover old harpoon points from the creatures, some of which the whales have been carrying for over a century. The oldest Bowhead, confirmed by biologists, was probably 211 years old at the time of its death and perhaps as old as 245.

Living exclusively in the cold northern seas, their venerable age, as National Geographic notes, is likely because of the cold environments in which they live. In the icy cold waters, Bowhead whales have low body temperatures, leading to slower metabolisms. While all living things experience some amount of tissue damage just as a result of living, a sluggish metabolism minimizes this, meaning that the Bowheads' freezing home is likely key to their longevity.

Greenland Shark – 272 years

The Bowhead whale may be the longest-lived mammal living in the chilly Arctic seas, but an even longer-lived animal shares the icy waters the whales call home. That animal is the Greenland Shark. These Arctic predators are very likely the Earth's oldest vertebrate animals of any kind. New Scientist explains How one individual shark was confirmed to be at least 272 years old and perhaps much older.

It's difficult to tell a shark's age with any certainty. Unlike human bones, the skeleton of a shark is made of cartilage. They don't keep any concrete record of their age with no mineral bones. To estimate the sharks' ages, zoologists needed to be creative, instead using traces of radioactive isotopes from 20th-century nuclear weapons tests, which were still trapped in the sharks' eyes. The results, understandably, carry a lot of uncertainty. Live Science notes that the maximum estimate for the oldest shark ever found is 512 years. But this is only an upper limit, and there's no way to be sure.

What is certain, however, is that the Greenland Shark can live for centuries. 272 is the minimum age estimate, and it's quite likely that these animals can easily live for over 300 years. Reportedly, they don't even reach breeding age until they're around 150 years old. Life in the world's coldest waters happens at a much more leisurely pace.

Welwitschia mirabilis – 1500 years

Only found in the Namib desert, Welwitschia mirabilis is a plant that is quite unlike any other. At first glance, it may not look like anything special — a frayed mass of tattered and leathery leaves. But, as the South African National Biodiversity Insitute explains, the welwitschia's disinteresting appearance belies just how unusual this plant is. For one thing, it only ever grows two leaves. Where most plants sprout as seedlings and then develop new adult leaves, welwitschias keep their original two baby leaves. These keep on growing; the only leaves the plant ever grows, eventually curling, splitting, and fraying with age.

Welwitschias routinely live for centuries. An average plant may easily be 500-600 years old, and its lifespan is between 400 and 1,500 years. The largest of them, however, may be as old as two millennia. Botanists are fascinated by these strange plants, with a study in Scientific Reports describing them as "one of the most extraordinary plant species on Earth." They live isolated lives in small communities, and they're carefully adapted to live in the arid desert soil, with long taproots to pull water up from deep underground.

Being so famous among botanists, Welwitschia mirabilis has even made it into pop culture on occasion. One notable example is DC's limited comic series "Poison Ivy: Cycle of Life and Death." A welwitschia plays a prominent role in the opening scenes of the comic's first issue, which makes a point to highlight its age.

Black coral – 4200 years

Not all of the ocean's longest-lived creatures live in the Arctic. Black Corals, as the Smithsonian notes, can be found growing off the coast of Hawaii, and they can reach ages of over four millennia. Corals are entire communities in themselves, each made up of hundreds or even thousands of individual polyps, as NOAA explains. While the word coral usually brings to mind colorful tropical reefs with azure blue waters and bustling communities of marine life, these tropical shallow-water corals are just one variety. Their deep water cousins are much longer lived.

The Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory discusses how marine biologists in 2009 realized that deep water corals around Hawaii were far older than previously thought. The black corals, so-called for their black mineral skeletons, aren't even the only long-lived coral in the Hawaiian waters. Their habitat is shared with gold coral, which can also live for a stunningly long time. One black coral was studied and found to be 4,270 years old, making it one of the ocean's oldest animals. Interestingly though, while the coral may be ancient, the individual coral polyps tend to only be a few years old at most. Individually, they're not especially remarkable. Their strength comes from the community they build together, and it's only as a collective that they survive for so long.

Bristlecone pine – 4853 years

Bristlecone pines are famous for their extraordinarily long lives. One among their number is the oldest single tree in the world, with an age of almost 5,000 years. Known by the name of Methuselah, the USDA explains that its exact location is kept secret to protect it from being damaged by any visitors it might otherwise receive. All they'll divulge is that it's growing somewhere in the Inyo National Forest near California's Sierra Nevada mountains. This forest is a land of ancients, known for its gnarled and twisted old bristlecones, with more than one having stood there for more than 4,000 years. Bristlecones are known for their dense, resinous wood, which helps them remain standing well into their old ages. In old age, their wood is the only thing that keeps them from collapsing. The oldest bristlecones are mostly dead wood, with only a handful of living branches connected to the tree's roots by a thin strip of living plant.

At 4,853 years old, Methuselah is believed to be the world's oldest tree, but recently a new challenger has appeared. As explained by Science, a tree in Chile known as Gran Abuelo may be even older. In addition, an Alerce tree (a distant cousin of California's sequoias) may have lived for a few centuries longer, possibly being as old as 5,400 years. While the claim isn't widely accepted, it's humbling to realize that a single tree could have been standing for longer than most of human civilization.

Armillaria solidipes – 8500 years

Many strange secrets lie under the soil, particularly beneath the old forests of the world. One almost-eldritch living thing is an enormous fungus. Its species name is Armillaria solidipes, but it's colloquially referred to as the "humongous fungus." Living under Oregon's Blue Mountains, this strange beast was discovered in 2001, as Science Daily explains, and it's estimated to be between 2,000 and 8,500 years old. Millennia ago, a single spore germinated somewhere on a forest floor. This fungal spore may have been no larger than a mote of dust, but, according to Scientific American, the organism it grew into has been declared the largest living organism on the face of planet Earth.

When most people hear the word fungus, they think of mushrooms, but most fungus remains permanently buried underground. There it spreads out as a network of fine filaments called mycelium. The immense Armillaria solidipes has seemingly been spreading outward this way for thousands of years, now covering well over 2,000 acres of the soil below Oregon. Mycologists measured its size by using DNA fingerprinting to work out where one fungus ends and another one begins. The fungi themselves recognize each other, distinguishing one individual from another and making it easy to tell one from another. As one scientist notes, sprawling networks of fungus-like this challenge our ideas of what it means to be an individual living thing.

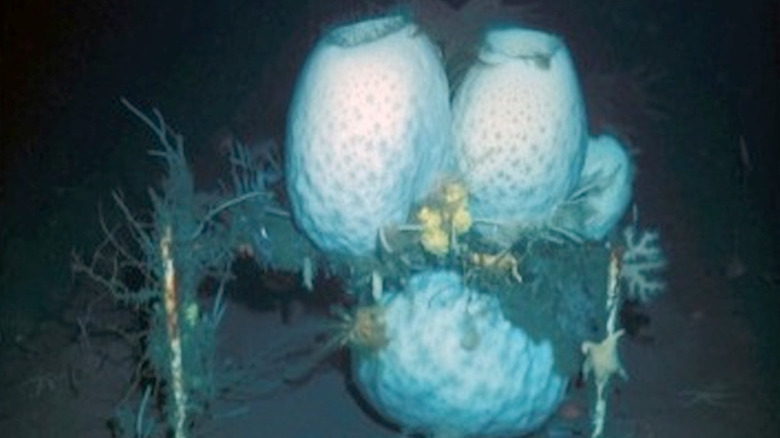

Glass sponge – 11,000 years

The oldest living animals on Earth, without involving any hibernation or suspended animation, are also among the simplest. As reported in 2012 in the journal Chemical Geology, a deep-sea glass sponge was found in the East China Sea and was estimated to be approximately 11,000 years old. With uncertainties in the measurements, it may even be up to 14,000 years old. This is old enough that the skeletons of living creatures like these can hold a record of Earth's changing climate since the last ice age.

New Scientist discusses another venerable sponge, this one in the deep waters off the Hawaiian coast. This sponge, the world's largest known, may also be thousands of years old. Unfortunately, working out the exact age of a sponge is a challenging endeavor. Glass sponges are so-called because their skeletons are made from biogenic silica. Simply put, they have "bones" made from glass. Unlike trees or other living things, a sponge's skeleton gives few clues as to its age, which is why any ages are just estimates with such a large amount of uncertainty.

As well as being Earth's most long-lived animals, sponges have a long history on this planet. As Nature explains, sponges may even have been the first true animals to live on Earth. Fossils have been unearthed, which appear to show sponges that lived 890 million years ago. If correct, this makes them the most ancient type of animal known to science.

Quaking Aspen – 14,000 years

The world's oldest tree is another living thing that challenges what it means to be an individual organism. Going by the name of Pando, and also known as the Trembling Giant, it isn't simply a tree but an entire forest all by itself! As Discover Magazine explains, Pando has roughly 47,000 individual tree trunks, all sharing an immense underground root system. Pando is huge. The heaviest living thing on the planet by quite a long way. The reason is that it has been growing for an extraordinarily long time. According to a 2007 paper published in Scientific Reports, Pando is estimated to be roughly 14,000 years old — though, with no single trunk to measure; it's difficult to be any more specific than this.

Pando is a clonal tree, meaning that each new tree trunk is a clone of the original, with identical DNA. Instead of reproducing from flowers and seeds, a clonal plant's daughters will sprout from its roots, giving the mother plant a direct boost of nourishment. Usually, these clones will detach themselves once they become established. Usually, but not always. In Pando's case, the trees still share the same roots, making them all part of the same tree. A 1996 study published in BioScience, speculates that clonal trees like Pando could potentially survive for a million years or more.

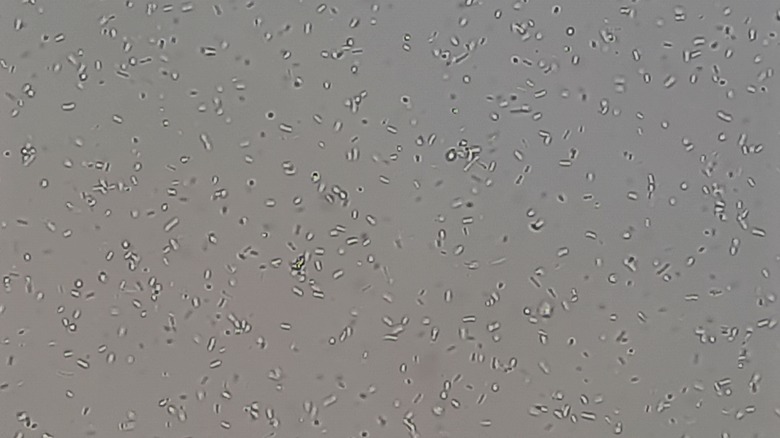

Bdelloid rotifer – 24,000 years

Rotifers are tiny freshwater animals. Microscopic but, unlike bacteria, they're multicellular and much more complex. They have an impressive set of survival skills, too, being able to survive boiling, desiccation, radiation, and freezing. Seemingly, they can comfortably remain frozen for an exceptionally long time. As Ars Technica reports, scientists discovered rotifers trapped in Siberian permafrost. The little creatures had spent 24,000 years deep-frozen in the tundra and survived.

Rotifers, as UCMP Berkeley explains, are common little creatures. They can be found living in a variety of freshwater environments, from lakebeds to rivers, and can also live quite comfortably in moist soil. According to fossil records, they've been living their microscopic lives on Earth quite happily for well over 30 million years. This is probably thanks, in no small part, to their remarkable durability. National Geographic notes their resilience, explaining that bdelloid rotifers can survive doses of radiation 100 times higher than that which would kill a human.

Being able to survive such extended periods on ice, rotifers frozen in permafrost may begin to wake up as climate change continues to melt the Arctic ice. When they do, creatures like these rotifers will inevitably start to reenter Earth's biosphere. While a rotifer isn't particularly scary (unless you happen to be a bacterium), it does raise the concern of what else might be waiting in the deep-frozen Arctic.

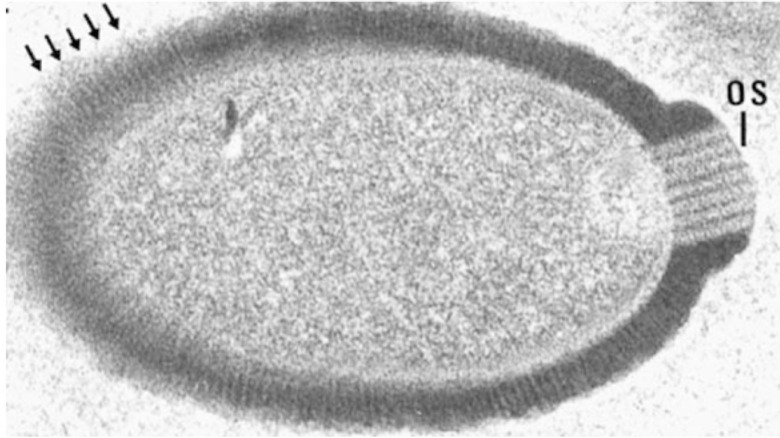

Pithovirus – 30,000 years

Viruses are not considered alive under the definitions used by most biologists. Giant viruses, however, are a specific type that muddies the water somewhat. A giant virus may sound like something from Star Trek but, as National Geographic explains, giant viruses are very real and occupy a gray area, somewhere between what biologists consider living and non-living. Since the first known giant virus, Mimivirus, was discovered in 2003, some biologists have argued that giant viruses should be regarded as a distinct form of non-cellular life. It's even been proposed that they should be considered a new, separate domain of life, alongside archaea, bacteria, and the eukaryote, which includes humans.

Pithovirus is the largest giant virus ever discovered, and according to Live Science, it was first discovered frozen in Siberian permafrost. In 2014, a team of researchers successfully resurrected a pithovirus that had been trapped in the ice for 30,000 years, making it the oldest "living" virus ever recorded. While this may seem like the premise from a horror movie, with ancient resurrected viruses the size of bacteria, there's nothing to be too concerned about. Giant viruses like Pithovirus, thankfully, only infect single-celled microbes. Most of them are known to hunt only amoebas.

King's Holly – 43,600 years

Pando isn't the only old clonal plant in the world. Another, in Tasmania, has an even stranger story behind it. Known as Lomatia tasmanica or, more informally, King's Holly, it's a shrub with an estimated age of at least 43,600 years. According to Amusing Planet, it may even be as old as 135,000 years. With an extensive shared root system, King's Holly is both a single plant and an entire grove of bushes. However, while this story may be interesting, it also has a sad plot twist.

A study published in the Australian Journal of Botany explains that King's Holly is also an endangered species. There's only one known wild population of King's Holly in the entire world. This one known collection of interconnected clones is all there is of this plant. In other words, not only is King's Holly vast and ancient, but it's also the sole member of its entire species still growing in the wild, where it's been contentedly cloning itself for millennia. As the most striking testament to its age, it's been growing for so long that its leaves have been found in fossils! King's Holly leaf fossils, apparently from the same plant still growing in Tasmania, have been dated to at least 43,600 years old.

Mediterranean seagrass – 80,000 years

The true oldest living plant in the world is a patch of seagrass growing in the Mediterranean, and it's the oldest by quite a long way. As New Scientist explains, this seagrass has an estimated age of between 80,000 and 200,000 years. This earns it a firm place as not only the oldest plant but also the oldest complex organism and arguably the oldest continuously living thing of any kind. A study published in the journal PLoS One elaborates further on the seagrass, which has the scientific name Posidonia oceanica. A seemingly humble plant, considering its great age, the seagrass has recently come under threat. As a result of climate change, shifting conditions in the Mediterranean have begun to endanger the habitat where Posidonia oceanica has been growing for what is quite possibly as long as humans have existed, at least in our modern form.

Like Pando and King's Holly, Posidonia oceanica is a clonal plant. While no one can be certain how large clonal plants can grow or how long they can survive, the oldest among them can quickly grow to vast proportions. According to Science Daily, the seagrass spans an area over 9 miles (15 kilometers) wide and weighs around 6,000 metric tons. An entire meadow of seagrass, growing on the floor of the Mediterranean sea, all of which is the same plant.

Ocean floor microbes – 100 million years

One thing about life on Earth is that while the larger and more complex living things may be the most impressive, the smallest and simplest are the greatest survivors. For example, there's a region in the Pacific ocean known as the South Pacific Gyre. According to The New York Times, it's been described as "the deadest spot in the ocean." However, living things can still be found even in such a desolate place. In the soil and sediment, buried under the ocean floor, scientists discovered a variety of microbes. Bacteria, fungi, and viruses are all languishing mostly dormant under the sea.

As Phys Org explains, these microbes are seemingly very much alive, and researchers believe they're around 100 million years old – an estimate based on the age of the soil in which they reside. The microbes haven't been frozen or in suspended animation, but appear to have simply been living in extreme slow motion, only reproducing once every 10,000 years on average. The fact that these microbes are still alive at all is a puzzle for microbiologists, leading some to be hesitant to even describe them as such. They've even been likened to being in a zombie-like state, still moving even if they aren't truly alive anymore. Among the other puzzles is the question of where these microbes get the energy to sustain themselves. Discoveries like these test the limits of Earth life and force biologists to think long and hard about what life is.

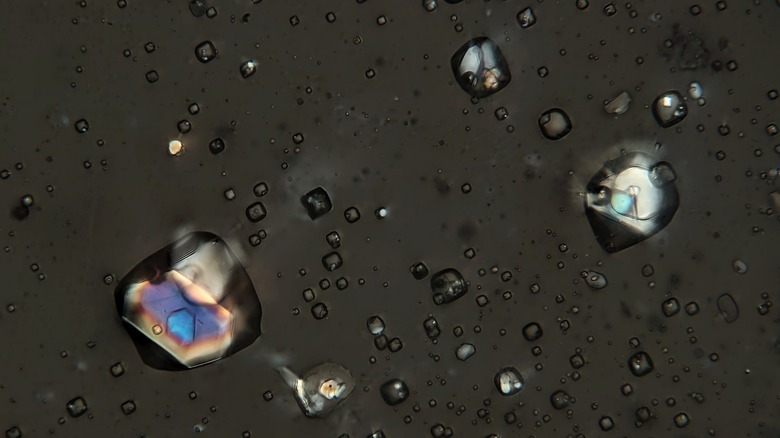

Australian salt microbes – 830 million years

By far the oldest microbes ever discovered still haven't been confirmed to be alive — but, perhaps bizarrely, researchers argue there's no reason why they shouldn't be. In 2022, scientists found a piece of Australian rock salt containing trapped microbes and, as Vice explains, these microbes are roughly 830 million years old. This is around 18% of the age of the planet itself (via National Geographic)! These trapped microbes are not only older than any previously found, but also older than most life on Earth. The rock salt they're encased in formed during the Precambrian Era before most scientists believe complex multicellular life even evolved. At the time, simple microbes like these were likely to have been the only kind of life on Earth.

Rock salt, technically known as halite, can contain fluid inclusions — small bubbles of trapped water sealed inside a tomb of crystalline salt. The 2022 Geology study explains that while there's no confirmation that these microbes are still living, there are several reasons to believe that they could be. Surviving in suspended animation, trapped in stone for almost a billion years. The most promising hint comes from a 2002 study, published in the International Journal of Radiation Biology, in which a different set of microbes were found similarly trapped in halite for 250 million years and were successfully revived. If single-celled organisms can survive this way for so stunningly long, there's no reason to believe they can't do so indefinitely.

Hydras – immortal

Senescence is the process through which living things slowly deteriorate with age (via Britannica). This may be a certainty for creatures like humans, but, surprisingly, it's a rule which doesn't apply to every living thing in the world. Hydras are small freshwater animals that don't age. As Live Science notes, they're biologically immortal. While no ancient hydras have ever been found, at least that we know of, the biologists who study them fully believe that they could live forever if given the right conditions. Given that they don't age, scientists have no easy way of knowing how old any given hydra even is. Their bodies are mostly made of stem cells, which keep them perpetually youthful.

Other creatures on Earth, however, manage to go one step further than the hydras. As the American Museum of Natural History explains, a sea creature named Turritopsis dohrnii can age backward. Known as the "immortal jellyfish," this strange animal responds to any physical injury by reverting to an earlier stage in its life cycle. In simple terms, it effectively has a second childhood before releasing a set of clones of itself and then maturing into an adult again. Theoretically, these jellyfish can do this as many times as they need to, and genetically identical jellies have been found all across the ocean. In more than one way, these creatures have truly learned how to live forever. They may not be Earth's oldest living things, but they could be someday.