The Strange Life And Death Of Taira No Masakado

Japanese culture has a pretty robust compendium of yokai—also known as ghosts. It's hard to find a yokai that doesn't have a fantastic story and/or origin, from the Tofu Kozo, who wanders around and offers travelers tofu — sometimes moldy, sometimes not — to the numerous yokai that dwell around the toilets of humans (some of which can be found on Owlcation).

Given the sheer multifacetedness of the yokai world, it should come as no surprise that one of the greatest warriors in Japanese history, when met with an unfriendly end, came back as a particular nefarious yokai that to this day can be found in need of appeasing from anyone in the near vicinity of where he may or may not be buried. You see, with Taira no Masakado, there are a lot of variables, in life, death, and everything in between.

Taira no Masakado is one of those rare individuals who lived an extraordinary life, had that life cut short, and then lived (died?) an even more extraordinary death, both in the manner in which he was killed, and in what happened afterwards which — spoiler — is an awful lot. Let's just say he was a busy man on either side of the death curtain. Here's a look at his strange life and perhaps even stranger death.

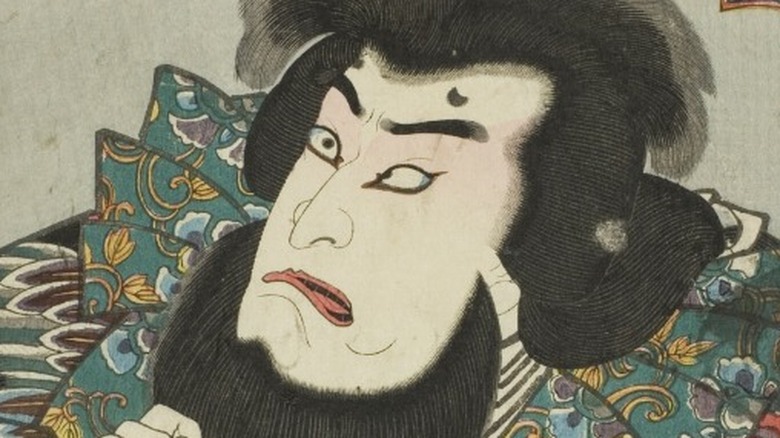

The first samurai

Generally speaking, being the first of anything is pretty impressive. There is only ever one first. For Taira no Masakado, not only was he the first at something, he was the first of an universally known warrior class that lasted for over a millennia—he was the very first samurai, according to KCP International.

Even to someone completely unfamiliar with Japanese history, the term "samurai" is practically universal. For one, they are a fearsome class of fighters that managed to survive for a thousand years (via Owlcation). The closest equivalent to the samurai are the traditional European knights, at least in terms of longevity and influence. Knights were like minor lords throughout feudal Europe, using battlefield expertise and their own land to exert dominion, and samurai were very similar, according to DK. Samurai are unique in the amount of skills they had, though. They weren't just fighters, they were artists, musicians, and more, as well as having to keep a presence in the court of their local daimyos and much more.

This rich history of power grounded in an honorable warrior class of multifaceted citizens of the world began with the original honorable warrior, Taira no Masakado, the man who established one of the world's most powerful groups.

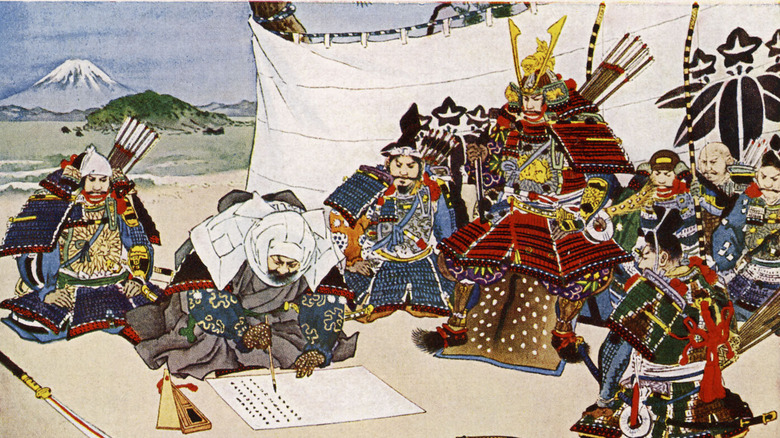

Rebellions against the government

When Taira no Masakado saw an ineffective central government in a budding Japan, he decided that it was time for a little shift in power, and who better to seize that power void than himself. Thus began the rebellion known as the Tengyō no Ran (according to KCP International), led by Masakado and his Taira clan. It began in 939 and it was all done by 940.

After being ambushed by the Minamoto clan in 935 — another mighty warrior clan in the Hitachi region, according to Japan Reference — Masakado hit back in a big way, burning his way all over the Hitachi province and killing a whole lot of regular people along the way too. While it might seem like the next step was to keep on the warpath and conquer all that could be conquered, Masakado actually stayed on the straight and narrow for a few years. He wasn't a power-hungry warlord, at least not yet. After a series of political maneuvers, Masakado found himself at his wits end and, with nowhere left to go, he had to either go big and seize central power for himself, or go home and suffer more incursions. Masakado chose big, and the rebellion began.

After a series of conquests, he then went all the way to the Emperor, who he then removed in order to make way for the new emperor: himself (according to Britannica).

Redistribution of power to the samurai

While the samurai class wasn't technically a thing at this point, it's seen as the origin point because it's the first time a self-governing class of warriors gained control of Japan. Masakado, while technically of the same lineage as the emperor, according to Japan Reference, was the head of a clan, just like the Minamoto clan he fought, and just like what would become the standard of the Japanese political scene going across centuries of feudal development. Over the centuries, Japan would see the emergence of some famous clans—from the early Minamoto clan to the unification under the Nobunaga clan.

But the first time that a clan of warriors was in a position of centralized power like this was the Taira clan, thanks to the conquests of Masakado. He put himself and his clan in power, without any real right to do so, and while his aim at doing so isn't clear due to the briefness of his reign, it's not unlikely that he would have sought some form of unification. And even though he didn't live long into his reign, his clan, the Taira, would be one of the most powerful clans as Japan entered this new, feudal era, according to Britannica.

A new, and very brief kingdom

Taira no Masakado worked hard to get to where he was. He played by the rules until the rules no longer made sense to him, and even then, it may well have been a conquest of necessity, or at least mostly necessity, rather than ambition. Regardless, when Masakado declared himself emperor, after a campaign that saw him off a number of relatives (according to Britannica), his fate was not far behind him. With a bounty on his head, he couldn't evade it for long, and after just two months of being in power, he was hunted down by a massive army compiled across provinces and was outnumbered ten to one (according to Japan Reference).

This army routed the Taira clan, ending the first ever established ruling warrior class and kicking off centuries of warfare between local leaders. In the end, it was his cousin who claimed Masakado's head (literally), bringing it to the court and sparking another chapter that would span centuries — the chapter of Taira no Masakado's head, his body, and how they never seemed to be in the same place at the same time.

Attempted burials

While it's easy to find a starting point for when Taira no Masakado's life got really interesting, it's harder to find a starting point for when his death took on a life of its own. What followed his death and decapitation at the hands of his cousin is where myth and reality blend together into a really satisfying and ambiguous answer, which amounts to little more than a bunch of theories. Most of which contain a sort of agreement that the attempted burial of Masakado is where all the spiritual problems began. According to Atlas Obscura, it wasn't until 1307 that a formal shrine to Masakado was constructed in order to calm down his feisty spirit. For those keeping track, that's about 450 years after his death.

There have been numerous shrines to Masakado throughout the centuries. The most well-known one today is in the Otemachi district, but two others include the Kanda Shrine and Tsukudo Jinja, according to KCP International.

The legends begin

When Masakado was killed, he had already dented the public image of the emperor by proving him a mere mortal, according to the Guardian, and that was all it took to give rise to a slew of myths and legends around the leader of the Taira clan. For starters, he was seen as something of a demigod according to KCP International, and the Guardian highlights the mythological origins of this idea. Apparently Masakado was completely invulnerable aside from the top of his head, which is the only place his serpent mother didn't lick—sort of like an Achilles heel scenario.

Then there is the matter of the natural phenomenon that people started to attribute to Masakado's rebellion. In the years leading up to his revolt, there were earthquakes and natural disasters, but there were also, and this needs to be quoted directly from the Guardian: "Plagues of butterflies" as well as rainbows that supposedly foretold of his challenge of divine rule. Just like that, Masakado had gone from a strong mortal ruler with an ambitious drive, to an immortal demigod with messenger butterflies.

As for his family, Masakado's daughter reportedly lived in the ruins of his family house, practicing necromancy, and trying to magically wield the collective power of frogs to bring back her father, according to the Guardian.

The separation (and loss) of the head

So much of the folklore surrounding Masakado has to do with his head. It's not even clear what exactly happened to his head, or when it was actually detached. According to Japan Reference, Masakado's cousin cut off his head and took it back to the capital, but according to the Guardian, his head was cut off in order to prevent Masakado's daughter from succeeding in her necromancy attempts at bringing him back. Apparently, it was then that the head was put on display in the capital, but according to KCP International, Masakado's head didn't rot for three months and his eyes kept rolling around in his socket for all that time. More than that, the Guardian says that the head howled at night, wanted to know where it's body was, and later flew away on its own accord.

And if you look at the legend around his yokai, it has nothing to do with his body and everything to do with his head, according to Yokai.com.

It's also possible that the separation of the head is what triggered the nether-worldly outbursts from Masakado's unruly spirit. After all, according to KCP International, his severed head was later found in a small fishing village, which isn't exactly a surefire way to ensure that a spirit is at peace. According to the Guardian, it was in this fishing village that the locals buried the head with honors, though a series of weather phenomena and lightening strikes hinted at the beginning of Masakado's tumultuous afterlife.

A return to power

Whatever happened to his body and head after death, Taira no Masakado had done serious damage to the image of this immortal line of the emperor, and it inspired a whole new line of warrior class upstarts eager to follow up on what Masakado had proven imminently doable. As such, rebellions began coming in hot and heavy and before long, what Masakado had done and managed for two short months became a fixture in the Japanese political landscape. According to the Guardian, it was all built on Masakado's saying that "The people of this world will always anoint their sovereigns through victory in combat."

When the warrior class seized control, they officially named Masakado the first samurai, as well as honoring his shrine in the capital of Edo, where the Shogun himself—the warrior class leader—was located. When a plague struck Edo, Masakado's angry spirit was seen as the culprit, and the people of Japan decided that it was time to acknowledge Masakado for what he really was—a god. According to Yokai.com, that's when he was inducted as one of the main gods of Japanese legend.

For hundreds of years, Masakado's spirit was quelled, and it makes sense why: His objective had been achieved, and he was seen as the forefather of it all. The warriors were in control through combat, and whatever immortal line the Emperor had was long gone.

The return of the Emperor

While Masakado was essentially venerated for centuries while the warrior class was in charge, that time came to an end with the return of the imperial line in 1868. The Shogun was overthrown, according to the Guardian, and the Emperor returned to the throne, thus ending the Japan that Masakado had sought to establish, and then found peace post-mortem in. The samurai, who had run Japan for centuries, were now seen as enemies of the emperor, and that included more than a few conversations about what to do with Taira no Masakado, the man who had died almost a millennia ago for the very principles the Emperor was now forcing out.

Despite knowing the history of his vengeful spirit, in 1874, Masakado was declared an enemy of the emperor. Emperor Meiji had gone to visit the shrine of Masakado and was less than pleased with this age-old samurai's divine status, so the emperor took that status away and moved the shrine out of the way, according to Yokai.com. That former shrine, his original plot of veneration, was soon built over by the new Ministry of Finance, and if you're thinking that Masakado's spirit wouldn't be happy with this, you would be absolutely right. If there's a such thing as waking an angry spirit, the new government of Japan had done exactly that.

The 1923 Earthquake

Following the 1868 ousting of the samurai, Masakado's spirit likely just took a while to wake up. In 1923, he woke up in a big way. The emperor had moved Masakado's shrine out of the way and, in its place, built his brand new Ministry of Finance. During the 1923 Tokyo-Yokohama earthquake, that building burned to the ground. The 7.9 magnitude quake was one of the deadliest, with the toll rising up towards 140,000, with the infrastructure of the city being largely destroyed, according to Britannica.

The earthquake created a tsunami that reached nearly 40 feet tall, killing another 60 and destroying 155 houses along the Sagami Gulf. There has been no comparable earthquake in terms of casualties in the history of the tectonic nation, and you can probably guess where this is going as it relates to Taira no Masakado. Connecting the dots, the government saw the long-dead, likely displeased spirit of the first samurai as the culprit behind the destruction. Apparently moving his shrine and removing his divine status was enough to stir him from a centuries-long slumber.

When the government tried to rebuild on the plot, 14 people involved were mysteriously killed, according to the Guardian, including the finance minister who used to call that building his workplace. In 1928, attempts were made to cleanse the land, but it wasn't the most thorough of jobs.

American occupation

Taira no Masakado's spirit was not amused by the new government's attempts to pacify him. After having peace for so many years under the veneration of the samurai of the Shogunate eras, he had been pushed aside, moved, built over, and improperly cleansed. Naturally, he wasn't done yet. In 1940, according to the Guardian, nine offices were struck by lightening in a phenomena reminiscent of the fishing village where Masakado's head flew. Two separate instances of targeted lightening strikes can only mean one thing—someone is displeased.

The government tried again to solve the issue, but then the Americans rolled in during World War II and, during the 1945 occupation, decided that this plot looked like the ideal car park. Plans were made and equipment arrived at the spot, a bulldozer started up, intent on starting the flattening of the area, and then the bulldozer overturned. According to the Guardian, locals blamed Masakado, and the American occupants were convinced that the land was cursed, and it is absolutely not, nor has it ever been, a car park.

Masakado's bank account

Anyone seeking to build on the plot of land formerly of Masakado's shrine has to be either completely ignorant to its history, or really desperate. It's unclear which camp the Mitsui Finance Corporation falls into, but they decided that this plot of land was the perfect spot for their new branch, according to the Guardian. While no death or physical destruction befell them, they went out of business in 2002. The Tokyo-Mitsubishi bank nearby decided that enough was enough. While Masakado was not a god in Japanese canon anymore, the next best thing they could do was give him his own bank account. The employees at the bank were supposedly told to not open any windows looking out at the plot, just in case.

As for the bank account, it's still in use today. According to Atlas Obscura, the original shrine of Masakado is in working order and kept presentable by a group of volunteers who use charitable donations to Masakado's account to fund their work at keeping this very active and often destructive spirit happy with his final (hopefully) resting place.